Ina, the poet

Remembering the moment when perhaps the most famous photograph of the People’s Liberation Struggle, “Kozarčanka” (Girl from the Kozara Mountain), was taken, one-time partisan nurse Milja Marin said:

“Even today, I don’t know how that smile in Skrigin’s photograph appeared on my face. I gave in to my emotions, although I did not feel like laughing, but I believed that my personal suffering at that time and the suffering of my family must come to an end.”

Indeed, the everyday challenges faced by nurses in the Yugoslav partisan army were numerous and draining because, as Ina Jun Broda, another wartime nurse, explained, to both doctors and the wounded soldiers the nurses “represented something between the ‘mother of God’, the self-sacrificing comrade and the ‘hospital bedpan’.” As a well-educated woman particularly inclined to poetry, Jun Broda expressed her weariness, her grief and compassion, but also the irony and mockery she sometimes felt in writing. The poem “Samokritika” (“Selfcriticism”) captures this combination of emotions well:

I confess, comrades, it is my fault.

It is my fault that I survived every assault

While the comrades died on the mountain peaks,

I still have all my limbs.

I confess, comrades, it is my fault:

I still don't know when was the third assault[1]

Because, during the political course,

I escaped to the park through the hospital doors.

I h a d to for a while be alone!

I enjoyed the evening's dark tone…

A petit-bourgeois song rising from my chest was so nice and fine

Yet it certainly was not along Party line...

Comrades, I confess that it is my fault

I sinned against the collective.

It is horrible: I would like to have my own home, my own dreams,

My own toothbrush,

my own shoelaces,

my own shoes –

my thoughts…

my comrade and his embrace

and my child…

I know, it is not right

because of my kid

to forget our orphans and their afflict

But I know that I would love that son of mine

even more than the Red Army and Stalin at the same time!

Sitting under Tito’s photo until late last night

I spoke to our hateful ally.

Joe is good and humble, honest and kind

And o u r s. But wounded – he was wounded only two times!

Three years of fighting and still head on his shoulder!

I don’t know, maybe he is not such a devoted soldier?

And so, comrade Commissar, I would like to be informed

Did I sin against our norms...

That’s all. Now let the comrades decide

So be it as they derive.

If I’m guilty, liquidate me.

Put a bullet through my head simply.

Perhaps it was meant to be –

The real consciousness, the new, has not yet been awakened in me

I’m confused and I have no one else to blame but me:

I still don’t know, comrades, how to live.

Should I follow fervor or head – a new blind allegiance

or the old compliance?

Cold discipline or my own ardor,

My heart or instead – the revolver???!

It is too hard, comrades, that’s why I said:

Bullet in the head. – But when they put me in front of a wall

once again I will boldly exclaim:

Death to fascism!!! – and freedom, freedom, freedom

for woman!

Translation: my own.

Poem: Samokritika is a part of Ina Jun Broda's wartime diary. It’s retyped contents, entitled Iz moje Crne bilježnice (From my Black Notebook), are kept in her archival collection at the archives of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

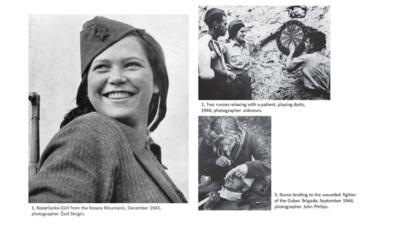

Illustration no. 1: Žorž Skrigin, Rat i pozornica (War and Stage) (Belgrade: Turistička štampa, 1968), 248.

Illustrations no. 2 and 3: Davor Konjikušić, Red Glow: Yugoslav Partisan Photography, 1941-1945 (Berlin and Boston: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), 214, 319.

Literature:

Kovačević, Dinka. “Mlada partizanka iz čitanke” (“Young Partizanka from a Textbook”). Nezavisne novine, June 8, 2007. http://www.nezavisne.com/novosti/bih/Mlada-partizanka-izcitanke/10554.

Bakšić, Lucija, Grubački, Isidora, and Jelušić, Iva. “Ina Jun Broda.” In Texts and Contexts from the History of Feminism and Women’s Rights in East Central Europe, edited by Zsófia Lóránd, Adela Hȋncu, Jovana Mihajlović Trbovc, and Katarzyna Stańczak-Wiślicz (forthcoming in 2023).

[1] The poet refers to the Third Enemy Offensive, one of seven major Axis military operations undertaken against the Yugoslav partisans during World War II, happening in the spring and early summer of 1942 in eastern Bosnia and in Montenegro.