Hannah Ibrahim was abroad when the war began in Al-Damazin, the capital of Blue Nile state, in September 2011. She was watching YouTube videos to get a grip on the situation when she recognized streets and locations. It was painful to watch. For her family it was even worse.

“They didn’t leave the house for three days as the fighting was inside the city. When my family left the house, the dead bodies were lying on the streets and inside neighbourhoods. My dad carried bodies with his bare hands with other people,” said Ibrahim who now works at the peace center at the University of Blue Nile.

Fatima Abakar, an academic who works at the Peace Studies Center at Nyala University in South Darfur has lived through the conflict that began in the Darfur region in 2003.

"It is not unusual to hear gunshots in the city."

“To be serious, I never feel completely safe in Nyala. It is not unusual to hear gunshots in the city. This insecurity limits my movement, I can’t go out after sunset because I am not sure what would happen to me,” said Abakar.

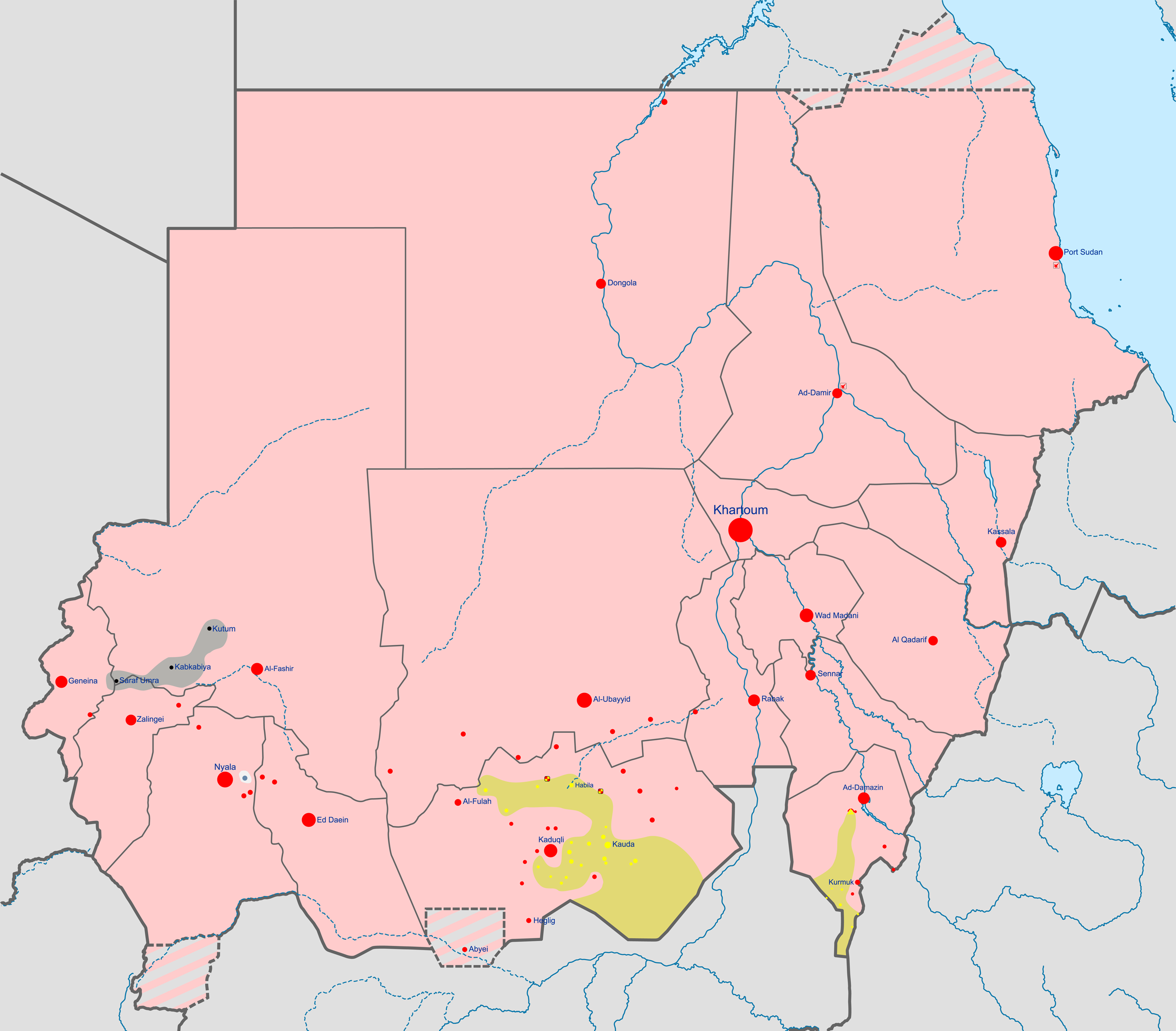

In South Kordofan, another conflict-ridden state in Sudan, Khansa Mohamed, an activist and academic working at the Centre for Human Resource Development at Al-Dallanj university, found herself alone after the state was thrown into yet another conflict in June 2011. The conflict was sparked by a rigged election that was contested by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North which was in a power-sharing agreement with the National Congress Party (NCP), the ruling party of the now-ousted government of Al-Bashir. The fighting that broke out in 2011 left the people of South Kordofan heaving for breath. The scars from the devastating conflict that raged all through the 1990s and came to an end with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005 had just started to heal.

“The war was unexpected, people had just settled down and life had returned to normal. We were working on Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) and the soldiers finally had choices other than fighting,” said Mohamed.

Yet, the war was both sudden and expected. Sudden in that fighting began so quickly and spread so fast with the SPLM-N retreating into the mountains. Expected because there were issues that were never resolved in the implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. The agreement was merely being held alive by the international community who interfered a number of times to stop the agreement from collapsing when the partners clashed. When war resumed in Blue Nile State and South Kordofan in 2011, several parts of the comprehensive peace agreement came to a halt.

As fighting resumed in the cities of All-Dallanj and Kadugli, the inhabitants had to flee. Mohamed’s family was one of them.

"I am sure I am not the only woman living under distress or living in an unfamiliar situation because of the war"

“My family moved to Khartoum, but I chose to stay at my job. I moved to the housing inside the university and I have to admit that since then, I’ve felt a great sense of instability. This impacted my professional life and delayed my PhD process as I am struggling to start it. I am sure I am not the only woman living under distress or living in an unfamiliar situation because of the war” said Mohamed.

Women at war

Hannah Ibrahim, Fatima Abakar and Khansa Mohamed are all too familiar with war and conflict. They have chosen to work in peace-building in an attempt to build their communities and improve the situation for women.

In South Darfur, women continue to be a majority of internally displaced people. It is women who bear the brunt of the ongoing tribal violence.

“When there is insecurity around you, making a living becomes difficult."

“When there is insecurity around you, making a living becomes difficult. Women mostly work as farmers or in the fragile informal sector and both sectors have high levels of violence. There is a conflict arising everyday in one of the localities which displaces more women and affects the precarious living of farmers. The economic empowerment of women in the state is constantly disrupted by violence,” said Abakar.

Women farmers in Darfur are the major targets of sexual violence. Poverty and a poor infrastructure mean that women have to walk long distances to the farmlands. The distance also forces them to stay there for weeks at a time. They run the risk of being raped at every point of the journey. Rape happens so frequently that older women often do the farming to protect younger women and to protect their sons because there is less stigma and sexual violence has been normalized.

People have fled from South Kordofan to other cities in Sudan ever since the 1980s.

“People have the right to move anywhere inside their country, but it is unfortunate that they are forced to do so due to conflict and it is also unfair that mostly women are forced to become displaced because they lose their families and they have to find ways to survive in the most vulnerable professions,” said Mohamed.

In Blue Nile, women are at the heart of the production process. They are farmers and they work in mining – perhaps the most dangerous profession for a woman.

Ibrahim has been following the process of women in the mining sector and as a researcher, she visits their sites and interviews them.

“Traditional mining means that women don’t have protection gear even though they use mercury. This results in miscarriages, deformed babies or stillborns. There is also sexual violence because they work in remote areas without any forces or policies to protect them,” said Ibrahim.

Enduring violence has affected the prices of gold. Ibrahim states that the market is controlled by companies or traders who purchase the gold for a fraction of its real value.

“They sell the gold at 20% of its cost or less and this is what I came to know when I visited Dandaro and met women there, they had no clue about the real price and were being exploited” said Ibrahim.

In South Kordofan state, Mohamed focuses on women’s education and employment prospects. She is not encouraged by what she sees.

"Many schools were closed and were turned into camps for the soldiers"

“Many schools were closed and were turned into camps for the soldiers, in the armed forces and in some cases for the SPLM-N, this affected women and upended their lives. They are not going to school because schools are few and the economic situation of the family is unstable because of the war. Those girls have limited choices, they work in the informal sector ,” said Mohamed.

In Southern Blue Nile, girls only get the chance to go to primary school. Only a lucky few get to go to middle school. Boys are sent to neighbouring towns to continue their education while girls’ educational journeys end abruptly to be replaced with early marriage.

“This is what we are working on, I know the problems in my state, I know that women face chronic violence, early marriage, displacement and other issues, they only persevere because the Blue Nile woman is strong and she is very productive and committed to working, we need to give them more choices in life,”said Ibrahim.

In Al-Dallanj, the tense and insecure situation complicates work for Mohamed.

“We keep hearing about killings, two months ago, soldiers were killed in an armed robbery inside the infantry in Al-Dallanj and this scared us. If soldiers inside an army premise can’t protect themselves, what do we do? I have to keep reassuring myself everyday while we wait for security,” said Mohamed, who continues her research at the university.

Did the revolution arrive for you?

Insecurity continues to be a lived reality for women in conflict areas. The revolution has yet to benefit them in their personal and professional lives. But there are slight differences.

In South Darfur, women can now organise in public, something which used to be prohibited.

“We have been organising since 2007 and 2009, but all our activities were secret because the former regime didn’t want women to become aware of its oppressive practices and of their rights, we started working online in the period before the revolution, now we are able to organise publicly,” said Abakar who is a member in a body called Darfur Women Platform which is coalition of women groups and activists working to improve the social and political situation for women in the region.

In Southern Blue Nile, access to some towns and villages were prohibited for civil society. They were not given permits by the security and other government agencies to work there and when they did, their activities were tightly controlled. Even for Ibrahim who works in a state institution, travelling inside the state required a number of permits from the military and the national security authorities.

"You would get stopped at three military checkpoints and you would get intimidated even if you had a permit"

“We were not allowed to go to Deram and it used to be difficult to work in that area, you would get stopped at three military checkpoints and you would get intimidated even if you had a permit, I just came back from Dandaro and Deram, I was surprised that we were only stopped once even though the military is still there, it was much easier,” said Ibrahim who used to struggle to work on human rights beforehand because it was a taboo topic.

Even the local community was more receptive to the work of Ibrahim and her colleagues because the villages she visited are considered in the middle ground between government and areas formerly held by the rebels and for many years, they were accused of being double agents and were harassed by both sides as a result. The communities are finally at peace now and can open up to the outside world without repercussions.

For Blue Nile, this opening of civic space comes after ten years of being a closed state.

"Former government officials have stolen many agricultural land and projects"

“I personally think they closed our state and intimidated us with extreme securitisation all this time to steal the wealth of the state. Former government officials have stolen many agricultural land and projects,” said Ibrahim who hopes that the current government gives back the land to the local communities.

Hannah Ibrahim, Fatima Abakar and Khansa Mohamed continue their work to build peace despite the militarisation of the states and despite the fact that the peace process that was signed in Juba in October 2020 has yet to materialise into a changed reality for women on the ground.