Scared, but still trying: stories of women activists working for peace in conflict areas in Sudan

By Reem Abbas, writer and researcher

Three years ago, in the aftermath of the December revolution, we profiled several academics who use their institutions and social networks to bring peace to their communities. At the time, they were operating with great ease within the general freedoms secured by the power of the people of Sudan through the revolution and they were able to reflect on what had happened to their communities during conflict and how they can work to achieve more sustainable peace. The three of them hailed and worked and lived in conflict-ridden areas. We are now returning to speak to Dr. Hannah Ibrahim and Khansa Mohamed as well as an anonymous academic and by speaking to them we are also getting a close look into how the conflict is impacting their states, South Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, respectively. The interviews took place over a number of days and were sporadic because of network issues.

When the profile was first published, the academics were living in states that had been affected by conflicts for a long time. Today, conflict has reached even the safest parts of the densely- populated Central Sudan. The war that began in Khartoum in April 2023 and then spread across Central and Western Sudan shifted the lives of everyone, especially women who were once again victimised by violence and also by the growing patriarchal narrative that wanted to blame them for the failures of the militarised political marketplace that centered around consolidating power in the hands of Sudan’s military institution. The violence against women during the conflict can not be untied from the great backlash faced by Sudanese women in the post-revolution period. The high demands put forward by women protestors and the way they challenged the public spaces led to the development of a narrative that painted women as partially responsible for the failures of that period from the economic situation to the political deadlock. “Madania” which was a popular slogan calling for a civilian-led rule became a word used to taint women on the streets and began to have negative connotations attached to women’s dress code and behavior. Violence increased and we saw higher rates in crimes such as honor killings. Sexual and gender-based violence picked up from the backlash and was largely carried out by state actors especially police forces during the crackdown on the protest movement and sadly, there was a strong narrative that “Madania” and loud voices of women were behind the deterioration in living conditions and this evolved into conveying that it is even behind this war. In a religious sense, any unfortunate event could be interpreted as a “test’ and social media became notorious for narratives on how we are being tested because we failed to protect our religious practises in the past few years. In this regard, it is not a coincidence that videos of women on social media, usually has commenters calling for the RSF to continue its rampage to bring people and especially women back to their senses.

The violence against women during the conflict can not be untied from the great backlash faced by Sudanese women in the post-revolution period.

Having said that, the violence against women during wartime was very intentional and an orchestrated campaign by the RSF to force entire communities to submit, to cause mass displacement and demographic change and overall, I am afraid that the end result is also pushing women out of public spaces with no schools or secure livelihoods in sight. The sexual violence orchestrated by the RSF should be a reminder that decades of impunity on this issue made it so integral to how war and politics are played in Sudan and for decades, the state itself used sexual violence as a tactic to silence dissent and the military used it as a tactic to intimidate communities.

The first academic we spoke to remains in Nyala city, the capital of South Darfur state and once the largest city after Khartoum. In October 2023, after months of battles inside the city, constant bombardment and attacks on the army’s 16th Infantry Division, the city fell to the RSF and the entire state was captured by the RSF in a matter of weeks. Many families fled to North Darfur which was still largely under the control of the army and continues to be the site of major clashes, however, many had nowhere and even no means to leave. They stayed behind and found themselves living amidst a total administrative secession from the state which now took Port Sudan as its administrative capital after Khartoum was essentially gutted by war, bombardement and major looting by the RSF and its allies. Administrative secession means that the state was no longer there, salaries were not paid and state institutions were not operating. Civil servants sat in limbo until some were absorbed, willingly or unwillingly, into the civil administration structures initiated by the RSF a few months ago to cement their rule in the state.

The running of the state has been left to the RSF which is a militia without a political project and it was starting to establish institutions and many activists and academics who wanted to serve their communities had to abide.

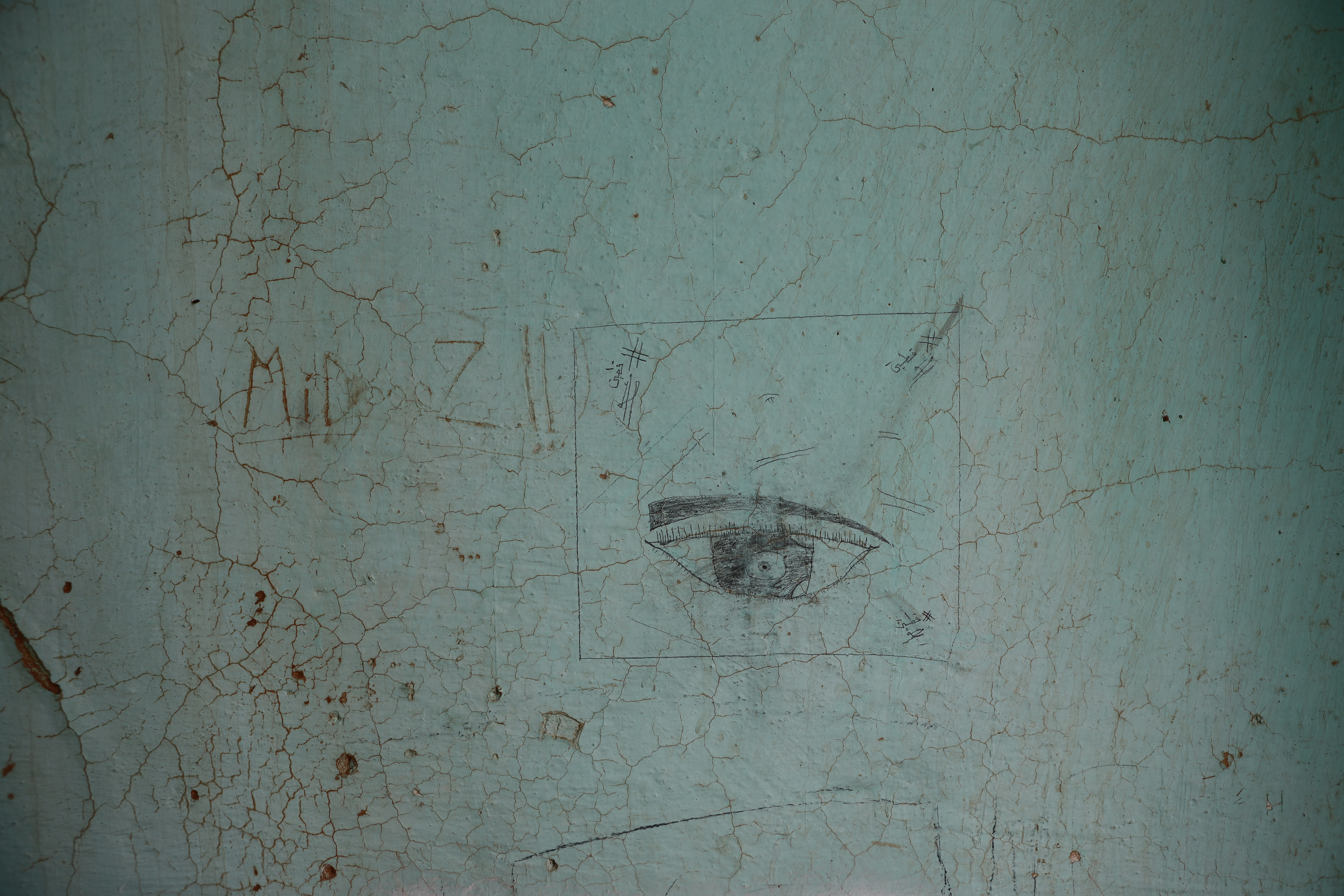

“Since the fall of the state, we have continued to work, but we are still very careful. Nyala university has mostly been bombed and that area where a lot of our work was concentrated continues to be under bombardment, however, I continue my work as a civil society activist,” said the anonymous academic.

To work in South Darfur and other parts under the control of the RSF, the civil society has to work under the Sudan Agency for Relief and Humanitarian Operations (SARHO) which was established by the RSF in August 2023 to replace the state-operated Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) and replicate its mandate (modus operandi) in areas under their control. SARHO doesn't have the administrative capacity or legitimacy of HAC, but it would state that it is facilitating the work of organisations as well as coordinating aid delivery.

“I am in many feminist associations and we get a permit from SARHO to hold workshops, our work has been focusing on helping women acknowledge and recover from the trauma they are feeling. We also support aid provision to families and women who are unable to survive otherwise and this is in coordination with national and international organisations,” the anonymous academic and activist.

Civil society in Nyala continues to coordiante with national universities and organisations to work on violence against women.To combat violence against women, the academic and her colleagues are working with women and youth and they tackle sensitive issues such as sexual violence.

“Right now, there is largely no education, so many youth are becoming part of the war machine through militarisation and recruitment, we are trying to deal with this as we understand that young men can’t even join the few operating colleges because of the economic situation. We feel that if youth find social and economic alternatives, we will see less militarisation and also less issues when it comes to peaceful coexistence, “ said our interviewee who added that they target youth they are the match that lights the fire and they want to protect their communities which has seen cases of rape and violence against women.

There is currently no fighting inside Nyala, however, there is still bombardment by SAF on the city as it is considered one of the main stations of the RSF. This has made her and many citizens there anxious about their safety.

“I am always scared about my safety and my children. When we hear the plane and the sounds of bombardment, I get very scared. I can’t do anything but pray, you have no idea how the bombardment cuts bodies into pieces,” she told us adding that “ I provide counselling to women who are traumatised by this war, but I also know that I need counselling. I am not well as I try to stay safe and also take up any consulting opportunity that comes my way to put food on the table.”

Hannah Ibrahim remained in Al-Damazin, the capital of Blue Nile state for over a year after the war began and left before Sinja in neighbouring Sennar fell into the hands of the RSF. Between 2019 and 2021, she was able to fully engage with her community through activities through the centre, but things turned sour in 2021.

“The first setback for me and for the centre was the 2021 military coup. The university’s administration was changed and sadly, the head of the peace studies centre was implicated in the ethnic violence that shook our state and that was between indigenous groups in the state and migrant groups that have lived there for a long time,” said Hannah Ibrahim.

Ibrahim found herself made inactive at the centre and completely isolated from work opportunities and also found herself targeted for her activism at the university lecturer’s union. “The head of the centre would hide invitations from me even if they were shared in my name. Under pressure, I quit my job as a lecturer because I felt that it is useless to enter into a battle with a group lacking ethics,” said Ibrahim.

When the war erupted, Ibrahim found herself drawn back to her natural position in activism especially for women.

“We started the initiative called mothers of Sudan and the main idea is to protest against the war and we felt the urgency to do so in Blue Nile because the state is militarised and historically, many young men were recruited here for fighting. We met mothers who had sons in the army and in the RSF. It was tragic,” said Babiker. Mothers of Sudan was one of the earliest groups to protest against the war and on the day they announced a protest against war, they found themselves cornered by the army and arrested.“I was on the way there when I was told about what happened and told not to come, we stopped communicating because of security concerns after some of the women remained in detention, it is very sad to see that the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) turn into the ousted regime and they began intimidating us,” said Ibrahim.

Ibrahim continued her activism in the state, but focused on supporting the displaced communities that were arriving there. Blue Nile which was a hotbed for tribal violence during the revolution became a haven for displaced families fleeing Central Sudan and this is mainly due to the efforts of activists such as Ibrahim. “When you met me during the revolution three years ago, I was an active agent, I was full of hope and optimism. I felt like I had a role. Now, I feel that my main responsibility is to save my life and the life of my family. We just want the right to live,” said Ibrahim.

Blue Nile which was a hotbed for tribal violence during the revolution became a haven for displaced families fleeing Central Sudan and this is mainly due to the efforts of activists such as Ibrahim.

From her current exile in Uganda, Ibrahim continues to speak about Blue Nile as well as document the experiences of women refugees in Uganda. As of October 2024, there were 60,000 Sudanese refugees registered across Uganda, with tens of thousands living outside the camps on other kinds of residencies.

In Al-Dallanj, once a lively trade and educational hub for South Kordofan state, Khansa Mohamed describes a situation similar to living in a refugee camp.

“For nearly two years, all the roads leading to All-Dallanj have been closed, we are completely isolated. Some women and children are smuggled out of the city and very few products arrive in the city, but at exorbitant prices. We have been hungry and children are malnourished, the communities in Dar Hamar have supported by delivering to us food items on the backs of camels and tok-toks and organisations have supported with seeds to help farmers grow some food, otherwise, things would have been worse. We have yet to receive any aid,” said Khansa Mohamed over whatsapp.

Khansa Mohamed continues her work at the university, but the university is only open for administrative work. There are attempts to open it to students, but this can only happen if the roads are re-opened.

“I go to work, we are given 60% of our salaries and I support in making ends meet with my husband and sisters who are with me, but I am helpless. My immediate family was under siege in Al-Haj Yousif, my mother passed away and I couldn’t even call them to offer my condolences for six months. It took me months to reach my father , my sister and my aunt,” said Mohamed as she described her personal living nightmare.

In 2021, Khansa Mohamed was trying to work for peace in her community, a region affected by war since the 1980s to say the least, but now the conflict is back on full-throttle bringing back many difficult emotions.

“We live in fear. Almost everyday, we hear the sounds of fighting around Al-Dallanj. The army still controls Al-Dallanj, but the fighting to take it continues. I thought about leaving many times and I tried, but it is even scarier. It is so difficult and unsafe to do so. I hope that this will end and in the meantime, I want to finish my PhD,” said Khansa Mohamed.