Irena, the actress

In the summer of 1943, Irena Kolesar joined the Yugoslav partisans. Having caught the eye of Šime Šimatović and Joža Gregorin, members of the theater group that was visiting her unit, she was invited to an audition. She spent the rest of the war acting in several major theater groups (and continued her successful acting career after the war ended).

In a 1972 interview for the Yugoslav magazine Start published in Zagreb, Kolesar testified to a common aspect of partisan life: “When things were most difficult for us, we sang. No one believes us today (…).” But many memoirs bear witness to singing in the most unexpected, oftentimes grim and difficult moments.

Irena Kolesar’s recorded memories also reveal an unsurprising but barely mentioned aspect of officially organized entertainment of the partisan war – that artists were usually bored by their assignments, and were also unwelcome and even slighted by their comrades in arms. Kolesar was not particularly straightforward about this. The reason, it seems, was her good-natured personality. Neither the theater colleague who “forgot” to return her trousers, nor the anonymous person who stole her shoes while she was sleeping (shoes were a valuable asset among the partisans, as many soldiers spent long periods of time in soft peasant footwear or barefoot), or even the fact that military units as a rule considered that actors were a burden and treated them accordingly, failed to affect her kind disposition toward everyone she mentioned in her texts and interviews.

Yet there are one or two interesting, negative observations in her small written legacy. These concern the partisan cultural evenings that usually consisted of theatrical performances organized for the civilian populations followed by informal socializing accompanied by music, singing, and dancing. These were well-attended events at which young village girls wore their best dresses. There were, however, always fewer men (usually only the members of the visiting theatrical group) than girls, and so there was a scramble for suitable dance partners. Because of this, Kolesar writes, female members of theater groups had to approach the guests and ask them to dance. She adds: “As uninteresting as that was to me, I know it was the same for those girls!” It comes as no surprise then, that if a partisan took a liking to a comrade – as was the case with Irena Kolesar and Šime Šimatović who eyed each other until he proposed to her in the summer of 1944 – he or she might find such arrangements tiresome. Moreover, the mention of the small numbers of the opposite sex at some of the partisan cultural evenings is an obvious allusion to girls’ desire to indulge in heterosexual socializing. In other words, the partisan cultural evenings, alongside the official emphasis on political and cultural education, were used by young people as opportunities to meet, mingle, and have fun, as in peacetime.

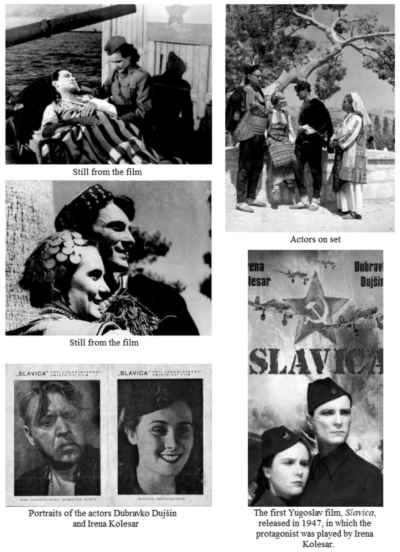

Illustration:

Vladimir Balašćak (ed.), Osmeh porculanske figurine (The Smile of a Porcelain Figurine) (Sremska Mitrovica: Društvo Rusina i Novinarska asocijacija Rusina, 2020), 14.

Literature:

Irena Kolesar, “Moji doživljaji, moja sjećanja” (“My Experiences, My Memories”), Dani Hvarskoga kazališta: Građa i rasprave o hrvatskoj književnosti i kazalištu 10, no. 1 (1983): 269-286.

Đuro Zagorac, “Još uvijek je zovu Slavica” (“They Still Call Her Slavica”), Start 80 (February 9, 1972): 26-28.