Crushing Hamas?

This blog post is written by Are John Knudsen, research professor at CMI.

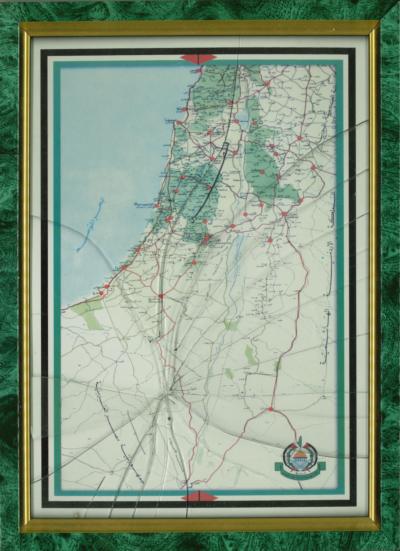

In May 2003, I met with the local Hamas representative in Lebanon’s largest and most unruly refugee camp, Ayn al-Hilweh. I aimed to understand the support for Hamas among Palestinian refugees in states bordering Palestine, particularly Lebanon. At the time, Hamas was an upstart but had already carved out a place for itself among the many secular and Muslim factions in the camp, and as a new contender challenging the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s (PLO) hegemony. Perhaps intrigued by my interest in the movement’s goals and aims in Lebanon, the interview was followed by a lavish lunch and, as I was about to leave, I was gifted with a framed map of Mandatory Palestine with the Hamas emblem imprinted in the lower right corner. The map came with me back to Norway, but as I unpacked my luggage, I found that the glass cover had been shattered during transport. In the many years since the map has been stowed away on my office shelf. The fateful terror attack on 7 October and subsequent Israeli onslaught on Gaza brought back the shattered map as a symbol of the Palestinians' quest for statehood and Israel’s aim of “crushing Hamas”.

The Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) emerged during the first Palestinian uprising (1987–93). The Hamas emblem signals the movement’s merger of Islam with armed struggle represented by the crossed swords in front of the Dome of Rock, the holy shrine in Jerusalem. Combining Islam with armed resistance is the hallmark of “Islamist” groups, but Hamas limits armed struggle to the liberation of historical (“Mandatory”) Palestine, depicted on the emblem as “Palestine” in text and imagery. The movement’s first charter in 1988 demanded the liberation of Palestine from “the river to the sea”, but has since offered tacit support for accepting a provisional state along the 1967 borders if approved by a “national consensus”, an example of the movement’s pragmatism that is often overlooked.

Research on Hamas has concluded that isolating the movement would radicalize it and play into the hands of extremists. Therefore, Western governments should maintain diplomatic relations with Hamas. A year after Hamas's election victory in 2006, conflict broke out between Fatah and Hamas, with the latter taking charge of Gaza. Soon after, Western governments ended formal contact with Hamas and redirected aid to the Palestinian Authority (PA). Since then, the limited humanitarian aid reaching Gaza has not stemmed growing unemployment, poverty, and ill health. This has been made worse by the near complete Israeli boycott since the 2006 war, the first in a series of deadly conflicts between Hamas and Israel until the start of the fateful 2023 war and suspension of food and medical aid to Gaza.

The Hamas leadership in Gaza has traditionally been more pragmatic and cautious than the “outer leadership” based in Qatar since they will bear the brunt of Israel’s attacks. The terror attack on 7 October across the heavily fortified Gaza border breaks with this mold. Why did the Gaza leadership endorse an attack killing 1,400 Israeli civilians and taking more than two hundred hostage, knowing that it would unleash a devasting counterattack? According to news reports, the Hamas leadership in Gaza – Yahya Sinwar and Mohammed Deif – concluded that Hamas could not remain a governing body of Gaza, but must commit to liberating Palestine. The fact that Israel was about to sign a peace deal that would normalize relations with Saudi Arabia, sideline Hamas, and bury the Palestine cause, played a role too. To break the status quo, Hamas concluded that a cross-border attack was worth the risk.

The human costs of Israel’s ground assault have been devasting, with targeted attacks on hospitals, homes, and schools breaching international war and human rights conventions. Twenty thousand Palestinians are killed and twice as many injured, in addition to the many missing among the ruins. Following the Israeli evacuation orders, 1.9 million people are corralled together in south Gaza living in makeshift tents, ruined homes, and huddling under plastic sheets. This has brought the conflict back to where it started in 1948: military defeat followed by mass displacement known as “The Catastrophe” (Ar. al-Nakba). As Gaza is being wiped off the map, a two-state solution has never been more costly and improbable.

Hamas’ military capabilities and underground command infrastructure are broken, but the claim to statehood is not. But now the stakes are greater than ever for both Israel and Hamas. Hamas has suffered a devasting military defeat but will not accept a watered-down statelet on the ruins of Gaza. Israel does not want a full-fledged state as its hostile neighbour and rejects the two-state solution as confirmed by the country’s ambassador to the UK. Still, the two-state track is promoted by the international community as the only long-term solution to the conflict. But as time has passed the West Bank claimed by Israel's right-wingers as the Holy Land (Judea and Samaria), is now but a Hollow Land, riddled with by-pass roads, outposts, and settlements that have colonized and fragmented historical Palestine.

Like the glass cover on the map of Palestine in my office, Hamas has been shattered by the Israeli onslaught, but not crushed. Behind the broken glass, the map of Palestine is unscathed and with it, the claim to statehood is shared among Palestinians across the political spectrum. But as the prospects for peace have shrunk, the price for achieving even a miniscule de facto state has continued to rise. This is akin to the allegorical fable of Sibylline the Seer offering the last King of ancient Rome nine books of prophecies that would guide him in any crisis he might face. The King rejects her offer of 900 silver pieces for the nine volumes until six are burnt and only three remain. Did he want to buy the last three? “Same price?” the King asked. “Same price”, she replied. “I’ll buy them”, said the King.

The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of CMI.