Reducing bribery for public services delivered to citizens

How to cite this publication:

Richard Rose (2015). Reducing bribery for public services delivered to citizens. : (U4 Brief 2015:11)

The literature on corruption tends to focus on grand corruption for contracts and licenses worth large sums of money. However, 1.6 billion people annually have to pay a petty bribe to get public services. In developing countries, such bribes reduce the effectiveness of donor aid intended to reduce poverty. Actions like replacing corrupt officials with computers, promoting more open government, and offering citizens a choice between institutions delivering a service can help reduce bribery in service delivery.

Citizens are most often in contact with government when they seek public services such as health, education, and police. In countries with corrupt public employees, people may need to pay petty bribes to get these services. Survey data indicates that 1.6 billion people annually have to pay a bribe to get public services. In developing countries, petty bribes can reduce the effectiveness of donor aid for programmes intended to reduce poverty. There are reforms that can help reduce bribery in specific services.

Public services such as education and health care give people skills to be productive and enable them to work effectively. The protection of individuals and their property requires effective and honest courts and police. Laws authorizing these services establish the conditions determining individual entitlements and obligations to comply with regulations. Having to pay bribes for these services violates the rule of law. Although the sums involved may be petty, they stimulate public distrust in government and reduce the quality of governance.

Many public services are personal services

Nurses, teachers or local government employees deliver services such as medical care and primary education. They live in the same community as the people who use the services. These public employees are very different from high-ranking officials who decide about multi-million contracts in return for grand bribes. Public employees are not automatons impersonally applying laws, instead they enjoy discretion in varying amounts. This is most evident for police who decide whether to arrest a person for driving recklessly, but it also applies to doctors who treat patients and teachers who deal with pupils.

Because contact with public services is a pre-condition of a person paying a bribe, the Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) survey of Transparency International asks people whether they or anyone in their household has used a variety of public services in the past year. Contact varies greatly between services. Whereas more than three-fifths make use of health services, less than one-sixth contact legal services (Figure 1).

Although the opportunity for public employees to demand bribes comes from their discretion and from contact with users, the extraction of bribes varies according to sector, country and specific local conditions.

Differences between services

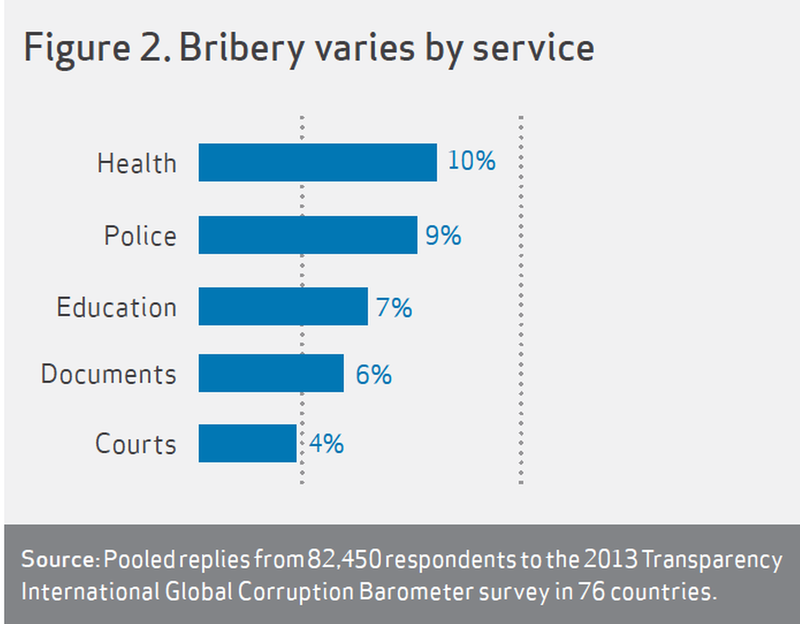

According to the Global Corruption Barometer, twenty-four percent of global respondents who contacted a service say they have paid a bribe.[i] Few respondents answer evasively or lack education and health care, thus two thirds of respondents must have dealt with public employees who do their job without demanding a bribe.

The service most subject to bribery is health care: one-tenth of all GCB respondents say that they have paid a bribe in the past year to a doctor, a nurse, a pharmacist or an official who controls hospital admission (Figure 2). This reflects the fact that people use health services more than any other programme. After controlling for level of contact, the police appear most corrupt. More than one-third of people who deal with the police report having paid a bribe. Among the minority dealing with the courts or getting a permit, between one-fifth and one-quarter report paying a bribe. By contrast, among people in contact with health and education, five-sixths report that they did not have to pay a bribe.

Differences between countries

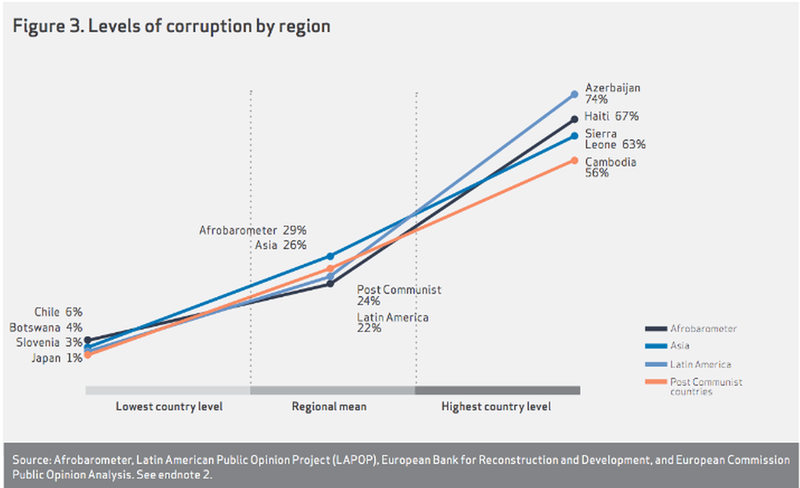

Differences in the experience of bribery are greater within continents than between them. The Global Corruption Barometer average of 24 percent of respondents paying bribes reflects a global range between 77% in Liberia and 1% in Japan.[ii] Surveys that cover dozens of countries within a single continent find big differences in bribery within each continent:

Within the European Union, the Communist legacy has left a few countries such as Lithuania with a high level of bribery, 29%. However, the average among EU member states is 4%; it is just as low in the Anglo-American world.

Statistical analysis finds that differences in bribery between countries are due to contrasting historical experiences and institutional choices. The 19th century introduction of bureaucracy in Europe results in less bribery today, whereas in many developing countries traditions of favouritism and clientelism weaken bureaucratic administration. The choices that governments make today also influence the extent of bribery. These include giving freedom to the press to expose corruption, eliminating regulations that create opportunities for extracting corrupt rents, and funding social services adequately or tolerating the scarcity that encourages bribery.

Differences within a country

Theories of political culture predict that in societies described as corrupt by Western standards most people would accept bribery as the normal way of getting things done. However, surveys consistently find that a substantial majority think it is wrong to pay a bribe, while the minority that considers bribery acceptable does not account for the existing levels of corruption. When there is a conflict between an ethical refusal to engage in corruption and the need to look after the health of family members or provide for a child’s education, people are prepared to pay a bribe as a lesser evil.

People pay bribes when public officials demand them as a condition for receiving a service or avoiding unwelcome sanctions. Among those who contact more than one public service, even when they have paid a bribe for one service, they are unlikely to have done so for every service they receive.

Governments cannot alter history nor one leader’s speech change the hearts and minds of citizens. However, there are measures that can help reduce public employees’ opportunities to extract bribes from users.

Actions government can take to reduce bribery

Creating an anti-corruption agency in the national capital may have symbolic value, but it is a long way from affecting how low-level public employees deal with ordinary citizens. However, governments can change the laws and institutions that determine how public services are delivered. Foreign donors can support the adoption of these changes by specifying conditions for the delivery of services that they fund.

Given the variety of opportunities that different services offer public employees to collect bribes, the best alternative is to have a tool kit including multiple types of actions. Some measures, such as repealing regulations, can reduce the demands that governments make on their citizens. Computerization can improve the efficiency and integrity of issuing permits and licenses. Actions focussed on reducing the payment of petty bribes for a single service cannot achieve the transformation promised but often not delivered by across-the-board proposals for reform. Yet a substantial reduction in bribery for a service used by hundreds of millions of people each year can save tens or hundreds of millions from being forced to pay a bribe. Actions include:

- Repeal laws that restrict the freedom of the press to cover corruption in public service delivery. Public disclosure of misdeeds should make officials less inclined to engage in corrupt practices. Donors can help open up government by making the publication of full details of each step in the process of awarding contracts for supported projects a condition for receiving funding. They can also promote the training of journalists and civil society activists in methods for identifying malpractice, such as monitoring public expenditure on a particular service across localities and regions.

- Review and clean up out-of-date regulations. Some outdated regulations serve little purpose except to allow officials to extract bribes. Officials have nothing to offer in exchange for a bribe if a document is not required. Fewer public officials can resort to bribery if fewer signatures are required. Reducing regulations encourages efficiency: people do not need to spend hours queuing in a government office to get a document and businesses can invest and innovate more readily.

- Replace face to face interaction with computers. Computerization removes a necessary condition of bribery, personal contact between a citizen and a dishonest public employee. Making a service, such as obtaining a license for an automobile or an appointment with a doctor, available online eliminates the risk of bribery while maintaining the service.[iii] Since websites are accessible any time, a web-based service is also more convenient for users and is less costly to maintain.

- Reduce discretion. Adopting automatised processes takes away the capacity of public employees to alter outcomes, which eliminates the opportunity to extract bribes from users. For example, the marking of student examinations, especially when markers can legitimately differ in their evaluations, creates opportunities for bribery. Multiple-choice questions are very suitable for administering and marking by computer. If the examination scores are posted on the websites of schools and universities where students compete for admission, this makes transparent the educational achievements of applicants and the qualifications of those admitted.

- Monitor public officials by electronic means. New methods for overseeing compliance and performance of public servants can help avoid some of the usual practices directed at avoiding detection. Agencies can install online biometric monitors in public institutions where attendance is slack to reduce absenteeism. Instead of signing in, an employee can register his or her fingerprint for electronic scanning. The agency can compare the fingerprints with its own records at headquarters. Failure to sign in electronically can give grounds for docking the pay of an employee absent without permission.

- Encourage the use of social media to denounce corruption and demands for bribes in specific services at the local level. Take advantage of the opportunities that new technologies provide to create social pressure against particular cases of corruption and to activate official channels of accountability.

- Expand choice. The public services that most people want, such as education and health care, are not monopoly services of the state, as are courts and military defence. In principle, not-for-profit institutions such as religious organizations, trade unions or agricultural co-operatives, as well as profit-making firms, can provide schooling and medical care. Giving people a choice between different providers of services makes it possible for an individual to refuse paying a bribe, because the service is available elsewhere. Vouchers that individuals can use to reimburse the services of schools or clinics can compensate for income inequalities.

- Legalize charges for faster treatment. In countries where bureaucracy is a synonym for slow service, individuals sometimes pay a bribe to get a service promptly. Adopting the practice of discount airlines and online retailers of offering faster service for a fee can legalise such illegal charges. For example, the British government will make a passport available to a businessperson in a hurry for an extra fee. A citizen wanting a new passport for a foreign holiday months ahead has no need to pay an extra charge. Providing a legal avenue to obtain faster processing eliminates the opportunity for bribery.

- Make public spending match individual entitlements. When laws offer hospital treatment to all citizens but the national government does not allocate enough money to provide hospital beds for everyone in need, this creates scarcity, and scarcity encourages bribery. Many people would rather pay a bribe than queue in pain for treatment or be off work because of illness. Reducing entitlements may reduce queueing but it also reduces the benefits of public services. Increasing the supply of desirable goods such as health care and education requires more public funding. Funds can come from transfer of expenditure from other policies. Advocacy groups can dramatise this by publicising, for example, how many teachers could be hired for the cost of one military aircraft. Since procuring military equipment is vulnerable to misuse of public procurement, transferring funds to local services can reduce grand corruption too.

Most of the above measures emphasise streamlining public services to make them more efficient and user-friendly, for example by reducing unnecessary paperwork and offering services on line. This makes the principles relevant in countries where bribery is low as well as in countries with higher corruption levels. Even if bribery is not a problem, governments everywhere are trying to lower the cost of delivering services and democratic governments are particularly under pressure to do so to satisfy their citizens.

The logic of targeting specific services’ features means that the measures set out above do not offer a ‘one size fits all’ solution. Nor can they apply to every step in the delivery of a public service. Computer-scored examinations can get rid of buying a good examination result but still leave teachers with significant discretion in how they treat individual pupils in their classroom.

In contrast with proposals to change national cultures or retrain officials accustomed to taking bribes, the foregoing principles emphasise structural changes that abolish the rents and jobs of corrupt public employees. The measures have multiple benefits, such as giving citizens more choice about how they deal with government on line or face to face, and whether they get services from a public or a private sector provider. These actions are within the power of a national government to enact and of donors to audit before making a final payment of aid grants.

Political opposition is inevitable among those who have a vested interest in maintaining practices from which they profit. The low-level public officials who collect petty bribes have less political power than ministers involved in grand bribery. Nor can those public officials easily organise mass protests against making services available more efficiently and honestly. A national leader effective in reducing the extent to which ordinary people are subject to bribery can gain political support.

The PDF version of this U4 Brief is available at http://www.u4.no/publications/reducing-bribery-for-public-services-delivered-to-citizens/

References

[i] See www.transparency.org.

[ii] See Richard Rose and Caryn Peiffer. 2015. Paying Bribes for Public Service, Figure 6.1. Details of surveys can be found at www.afrobarometer.org, www.ebrd.org, www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop, and www.ec.europa.eu/public_opinion.

[iii] See Hasan Muhammad Baniamin. 2015. Controlling corruption through e-governance: Case evidence from Bangladesh. U4 Brief: 2015-5. http://www.u4.no/publications/controlling-corruption-through-e-governance-case-evidence-from-bangladesh/#sthash.f872Dg00.dpuf

Further reading

Boehm, Frederic. 2014. Mainstreaming anti-corruption into sectors. U4 Brief.

Heywood, Paul M., ed. 2015. Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption. Abingdon: Routledge.

Johnston, Michael. 2014. Corruption, Contention and Reform. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, Richard and Peiffer, Caryn. 2015. Paying Bribes for Public Services: a Global Guide to Grass-Roots Corruption. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

ANTICORRP Anticorruption Policies Revisited.