The ‘Joyce Banda Effect’: Public Opinion and Voting Behaviour in Malawi

How to cite this publication:

Tiyesere Mercy Chikapa (2016). The ‘Joyce Banda Effect’: Public Opinion and Voting Behaviour in Malawi. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 6)

In the 2014 elections in Malawi, the incumbent female president Joyce Banda lost the presidency, and the number of women MPs was reduced from 43 to 33. This decline in women representation came despite opinion polls showing strong support for women’s political rights and for equal gender representation in politics. Why has women’s representation gone down when public attitude surveys indicate strong support for women?

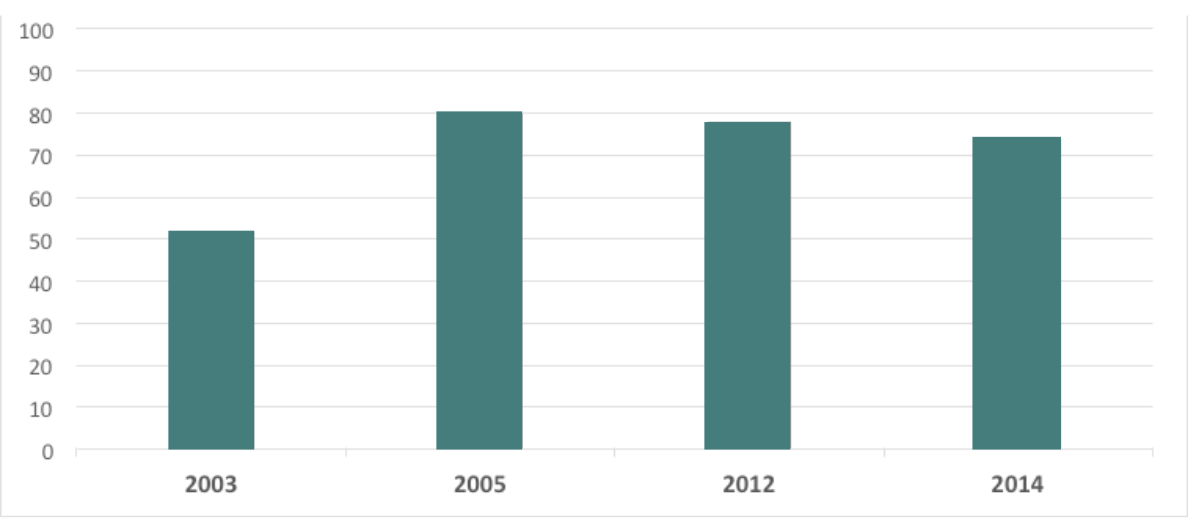

In 2003, the Afrobarometer survey asked respondents to indicate if they agree that women should have equal rights and should receive the same treatment as men, and 52 per cent of the respondents were positive to this. In 2005, this had increased to almost 80 per cent of the respondents, and in 2012 the overwhelming majority was still of the opinion that women should have the same chance of being elected to political office as men.

However, in the 2014 elections in Malawi, President Joyce Banda lost the presidency, her party (the People’s Party, PP) got only 18 per cent of the votes, and the percentage of women in parliament went down from 22.3 to 16.7. It seems that Joyce Banda dragged herself and others down.

In this brief, we will try to unravel this puzzle, using two possible and plausible explanations. First, there could be a methodological problem with the opinion polls, the so-called ‘social desirability’ bias. That is, respondents have a tendency to provide answers that the respondents believe is ‘correct’ or ‘socially acceptable’.

Secondly, it could be a problem of ‘role-modelling’: the performance of a particular representative has a tendency of shaping public opinion and future attitudes on that representative and on what he/she represents. That is, the failure of the woman president may have brought down the popularity also of other women politicians.

Stable Opinion and ‘Yeah-saying’

In order to assess whether there has been an opinion shift among Malawians on women’s suitability for political leadership, I conducted a survey that cross-checked and updated the 2005 and 2012 Afrobarometer surveys. My questions were similar to that of the Afrobarometer: should women have equal rights and receive the same treatment as men, and should both sexes have the same chances of being elected to political office?

I found that the large majority of the respondents were of the opinion that women should have equal rights and receive the same treatment as men, and that women should have the same chance of being elected to political office. I found only a small downward trend in the number of people holding this positive opinion (from 80 per cent in 2005 to 74 per cent in 2014). The figure below shows the percentage for respondents holding a positive opinion on the two statements.

Source: Afrobarometer and author’s own survey conducted in 2014.

Note: In 2003, the statement was “In our country, women should have equal rights and receive the same treatment as men do”, and in 2005, 2012, and 2014 the statement was “Women should have the same chance of being elected to political office as men, and should both sexes have the same chances of being elected to political office?”

Despite this strong and stable positive opinion on women’s participation in politics, when people went to vote in May 2014, the electoral outcome did not reflect the reported popular opinion. There was a marked decline in the number of women who made it to parliament. As I found no marked opinion shift, some explanation was needed to the inconsistency of a seemingly stable and positive opinion and a marked decline in people voting for women. It could be the so-called ‘social desirability’ bias of opinion polls.

Unfortunately, it is inevitable that people will try to present the best possible picture about themselves when self-reporting, and it is particularly so in opinion and attitude surveys. People are often unwilling or unable to report accurately on sensitive topics for ’ego-defensive’ or ‘impression management’ reasons, thus providing answers that the respondent believes are ‘politically correct’ or socially acceptable. This tendency of ‘yeah-saying’ can significantly distort the data and the analysis made.

There are tendencies of ‘yeah-saying’ in attitude surveys

This social desirability bias is an issue when research involves collecting data on personal or socially sensitive issues, like for instance politics and gender, which is under scrutiny here. The respondents may believe that society expects them to support women’s participation in politics, and they might indicate a woman friendly attitude even when they do not believe in women’s political leadership abilities.

Indeed, the social desirability effect can help explain why women performed poorly in the elections, even when people had expressed consistent and positive attitudes towards women’s political participation in the different attitude surveys. The social desirability effect goes a long way in explaining the contradiction.

Performance and ‘Role Modelling’

Aside from the so-called ‘social desirability’ bias, there are some more substantial possible explanations to the inconsistency of a seemingly stable and positive opinion and a marked decline in people voting for women. The most pertinent are the structural and circumstantial explanations.

Structural Explanations

Many studies have looked at the structural factors that may shape women’s access to political office, and some have found that the percentage of women in politics and in parliament tends to be higher for instance in countries using electoral systems with proportional representation than in those with majoritarian (‘first-past-the-post’) systems, like in Malawi.

They have also found a link between education and women participation. In countries with more educated women, there are more women in politics. Furthermore, the so-called ‘incumbency advantage’ is found to reduce the chances of members of previously excluded groups to make it into elected positions. Because the men are already in, they enjoy the advantages of being in office and of incumbency more than women do. Traditional gender role socialization is also an explanation that scholars give to low women representation, when the prevalent view is that politics is a domain better left to men.

These mainstream structural factors cannot, however, explain Malawi’s recent fall in women representation, because there has been no significant changes in the electoral system, in the educational level of women or in gender role socialization (at least not for the worse), and the ‘incumbency advantage’ factor should not reduce the number of women.

The only little structural factor that has changed is the ‘50-50 campaign’, which was launched prior to the 2009 elections, financed and supported by donors in order to increase women participation in the parliament. Prior to the 2014 elections, the additional funding made available to women candidates under this campaign was reduced. Other than this, I cannot confidently argue that structural factors like election system, education, etc. have worsened for women candidates since previous elections.

Circumstantial Factors

Thus, in order to answer the question of why women performed so badly in the 2014 elections, we will have to focus on the circumstantial factors.

One circumstantial factor is the gender stereotypes that continue to be used by media in covering electoral campaigns. When the media rely on certain stereotypes when covering male and female candidates, and when this reliance creates differences in coverage, then media treatment will have important consequences for voter information and candidate preference.

Other circumstantial factors came to the fore with my interviews. In addition to the distribution of questionnaires, I held 14 focus group discussions with people from seven district, with a fair representation of different social groups. Here, the symbolic or ‘role-model’ factor came out as particularly important. To a large extent, women politicians shape the social roles of women in public life, and consequently the performance of women in power will affect the perceptions and attitudes of people towards women.

When I asked the participants to consider why women failed to win more seats in parliament, the dominant view (28.5 per cent) was that “women have shown less capability to lead” and “women had little support”. Other explanations were that women had less education, fewer financial resources, etc., but only ten per cent or fewer of the respondents forwarded these and other explanations.

In other words, our respondents argued that the main reasons for the low support for women were that women politicians had shown little capability to lead, and that they had little popular support. I believe this is an indicator of the so-called ‘Joyce Banda effect’: the voters were demotivated by the performance of former President Joyce Banda.

Furthermore, I consider the so-called ‘cashgate’ corruption scandal to be particularly harmful. Following her ascension to presidency, Joyce Banda managed to gain donor confidence within a few months, but later her leadership became associated with this massive ‘cashgate’ public sector corruption and financial scandal. As stated by one women respondent:

“This has made voters to believe that a woman cannot be a political leader.”

This was echoed by a male discussant:

“What happened under the leadership of Joyce Banda made voters doubt women’s capability. Broad day-light stealing of millions of kwacha made voters doubt women’s capabilities in leadership positions like that of members of parliament.”

Media coverage of cashgate.

Corruption and mismanagement of public funds was not unique to Joyce Banda’s reign, however, as the male presidents before her also exhibited high levels of corruption. During Kamuzu Banda’s dictatorial leadership, corruption prevailed unchecked, and referring to it was almost taboo. During Bakili Muluzi’s second term, Malawi’s credibility among international donors tumbled because of corruption, and the donors withheld nearly USD 100 million in budget aid. Similarly, under Bingu Wa Mutharika and especially in his second term, Malawi experienced high corruption rates as well as misuse of public funds, like when he purchased his own jet airplane.

Thus, although this systematic and systemic corruption cannot solely be attributed to one female president (who furthermore ruled for only two years), it is still an important circumstantial factor. The cashgate scandal broke under her reign, and contributed to the weak electoral performance of women in 2014.

Apart from Joyce Banda’s performance as president, the participants of our survey and group discussions also pointed to the bad performance of other women MPs, which reduced the chances for female candidates in general. To some extent, this reduced the incumbency advantage of the women who had been in position. Our discussants argued for instance that female MPs did not accommodate constructive criticism, and sometimes they were rude. One discussant said:

“It is difficult to approach women because they don’t want to accept any constructive criticism. We had a female MP, […] and when we offered our advice she used to shout at us saying we shouldn’t bother her, she was educated, and scorned at us illiterate people who were difficult to handle.”

Moreover, there was dissatisfaction with women that had previously occupied different public positions and then stood for parliamentary elections. An all-male discussion group in Blantyre was of the opinion that most of the women who contested during the last elections were not really new in politics (since they had held public office they were close to politics), and they had not done a good job. According to one of the participants,

“The majority of these women had served in government positions in various capacities previously and had not performed to the expectations of the people as such voters were not willing to elect them.”

These extracts show that women did not have much of an incumbency advantage, in fact their incumbency and previous performance might have disadvantaged them.

People were judging potential female candidates based on the performance of a few incumbents, and the role-modelling effect was negative. The (deemed) negative performance of a few particular representatives shaped the voter’s attitudes and choices.

Policy Implications

Although the performance of women in elections has been increasing significantly in Malawi, it has always been far behind that of men. Moreover, the gap between men and women’s performance was even wider in the 2014 elections. I will therefore suggest the introduction of gender quotas. In this case, the quotas will ensure that no matter what happens (whether there is a change in structural or circumstantial factors), women will always constitute a certain percentage of the members of parliament. This will ensure that there are meaningful strides as well as consistent representation of women in politics, and ensure that women “are not only a few tokens in political life” as is the case presently in Malawi.

CMI and the Department for Political and Administrative Studies (PAS), University of Malawi, has a joint research project on Democratisation, Political Participation, and Gender in Malawi financed by the Norwegian Research Council. This CMI Brief is an abbreviation of a chapter in the book Women in Politics in Malawi, Inge Amundsen and Happy M. Kayuni (eds) (forthcoming September 2016).