Corporate Social Responsibility in Islamic Economies – the Case of Sudan

How to cite this publication:

Ahmed Elhassab Omer Elhassab and Abdelmageed Mohammed Yahya (Dilling University) (2016). Corporate Social Responsibility in Islamic Economies – the Case of Sudan. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (Sudan Working Paper SWP 2016:1)

Introduction

Since the 1950s, there has been a growing international awareness of the need for business organizations to commit to a social role that goes beyond the sole objective of profit maximization. The term “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) refers to strategies whereby corporations or firms conduct their business in a way that is ethical, society friendly, pro-environment and beneficial to communities in terms of development. According to Carroll (1979, 499), whose definition has been widely accepted, CSR can be defined in terms of four expectations, framed based on economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary responsibilities.

- Economic responsibility is for the business to be, first and foremost, profitable and viable.

- Legal responsibility is to obey the laws and regulations of the land.

- Ethical responsibility covers society’s expectations of business over and above the legal requirements—responsibilities that embody ethical norms, which are not necessarily codified into law.

- Discretionary (philanthropic) responsibility is the expectation that the firm will assume social roles over and above those already mentioned and caring for and investing in the society in which it operates.

CSR would seem to fit well with basic principles operating in Islamic-based economies like that of Sudan. Banning interest, shunning unlawful business investments, staying away from unclear or suspicious transactions, and above all, being oriented towards social justice and economic equality are main principles which underlie the claims of such economies to being distinctively Islamic.

These were also the principles upon which a number of development corporations (DCs) were established in South Kordofan State (SKS). The area is located at the border with South Sudan (which achieved its independence in 2011), and has been heavily affected by civil war. Driven by religious ethics and values, the corporations are expected to contribute towards reducing local socio-economic inequalities. Operations shall be conducted in compliance with Shari?a laws. Conversely, circumventing Shari?a principles would negatively affect, distort, and jeopardize the core objectives of any Islamic business.

The aim of this study is to determine whether there is convergence or divergence between such norms and values and the actual performance of companies operating in South Kordofan. The period under study goes from 2005 to 2011, which mark the beginning and the end of the interim period stipulated by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the Sudan Government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). This period witnessed the biggest influx ever of development corporations in South Kordofan.

Development interventions in South Kordofan

Massive efforts at modernizing agriculture in South Kordofan started in the late 1960s, when the Nuba Mountain Agricultural Corporation was established. The corporation’s main objective was to develop agriculture and strengthen the economy of the country as well as raise the living standard of local populations. Three ginning factories were built for processing cotton for export.

This represented the first real contact of the area with the international economy although export-oriented cotton cultivation had been introduced during colonial rule (1923). While the government and the shareholders achieved economic success, local communities did not benefit from it much. Socio-economic services linked to electrification, water supply, schools, health facilities, and roads were only established around the areas surrounding the factories for the sole objective of serving their working staff.

During the 1970s and 1980s, large areas of agricultural lands were distributed among private and public sector companies, cooperatives and individual farmers. Earlier, the government had also established some medium-size food-processing industries like the Babanusa Milk Factory (1964) and the Kadugli Textile Factory (1960). Because of poor planning, inefficiency and corruption, many of these enterprises soon ran out of capital, were mismanaged and collapsed.

Once again, the issue of corporate social responsibility remained of minor concern to the investors. Making as much profit as possible was the driving force, not social commitment. Even the payment of the annual religious tax, zakāt, on agricultural products was coercive.

Beginning in 1983, South Kordofan was drawn into a long-standing war between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the central government. The war lasted 21 years, adversely affected the social fabric of the state and demolished its already poor infrastructure. In 2005, the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the government and the SPLM gave new hope. The agreement accorded a special status to the “Three Areas”: Abyei, South Kordofan and the Blue Nile State. Preferential economic and political treatment was given to those areas in order to heal social ruptures and build new foundations. The door was also opened for non-governmental actors to engage in development efforts, including the private sector. Thus, the government passed a new investment regulation with generous concessions to attract national and foreign capital.

South Kordofan soon became a fertile territory for many development corporations with different projects and objectives. Over the short period of time between 2005 and 2010, the state witnessed the biggest influx of companies ever. They covered different sectors—financial institutions, communication services, oil exploration, transportation facilities, etc. Currently, there are twelve banks, two credit institutions, four insurance companies, two communication companies, one oil producing company, and more than twelve transportation companies in the state.

Objectives and approach

In light of their allegedly strong commitment towards Islamic ethics and social betterment, the development corporations would be expected to prioritize their work to projects and investments that have positive social impacts and are geared to enhance economic equality and social justice in the society. This study raises the following questions:

- Is there any commitment to CSR towards local communities?

- Which CSR issues concern local communities?

- Are development corporations (DCs) in South Kordofan reactive, defensive, accommodative or proactive towards CSR?

The use of a benchmark table is aimed at answering these questions. The table has two purposes: to map different aspects of accountability and social justice that are regarded as unique for businesses working under Islamic conditions; and to facilitate analysis of the actual CSR conduct in each of those aspects. The reasons for the conformities and disparities between the ideals mapped out by our benchmark, and the practical performance of CSR in the DCs, are also discussed.

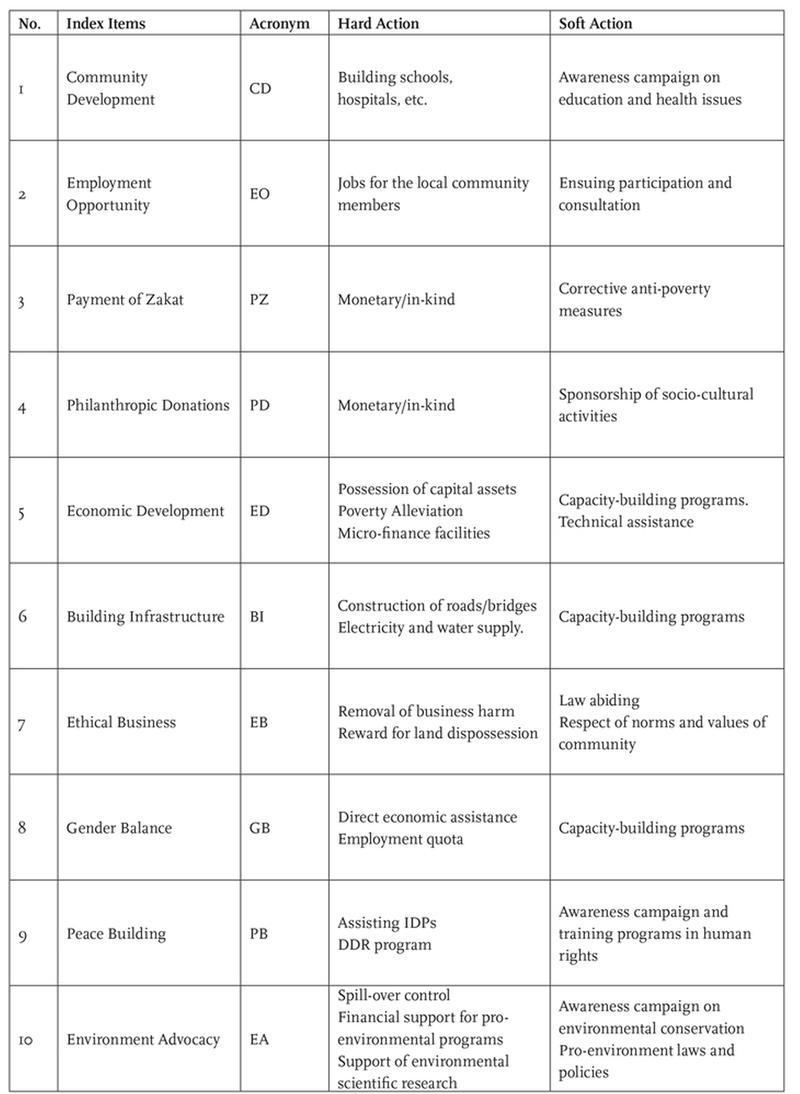

The benchmark covers ten main themes, some of them crafted by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), others derived from the literature on CSR as well as the authors’ own contributions.

DCs are expected to take or avoid several actions as they seek to contribute to social justice and economic equality in their communities. These include engaging in community development projects, providing job opportunities for locals, paying zakāt, providing charitable donations, making interest-free loans to the disadvantaged, extending micro-finance credit on affordable terms to small enterprises and entrepreneurs, taking account of the natural environment when making investment decisions, and providing full and accurate CSR disclosures. Actions to be avoided include carrying out unlawful business operations or indulging in illicit practices such as fraudulent transactions and dishonesty.

The categories are divided into hard and soft actions, as shown in the table below.

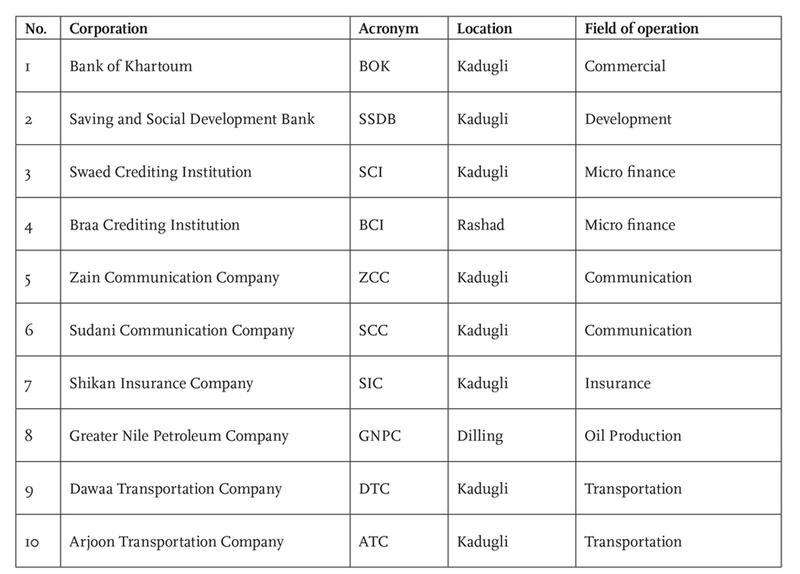

The selected sample consists of 10 companies working in diverse fields. All operate according to the laws and principles of investment in Sudan. They all claim to be socially responsible companies and include two banks, two communications companies, two transportation companies, two oil companies, one insurance company, and one commercial company.

The content analysis at the core of the study is based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative assessment of data provided by the companies in their annual reports and reports of social performance during the years 2005–2010, supported by interviews carried out among high-ranking company officials during 2014. By benchmarking the CSR conduct of the DCs to standards promulgated by the AAOIFI and articulated in the literature on Islamic business, the study aimed to assess the level at which DCs undertake socially responsible activities, consistent with their claim of Islamic identity.

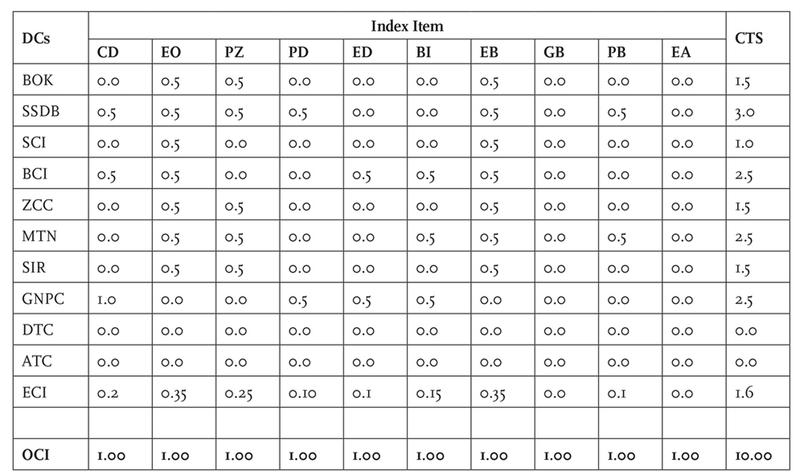

We have used a conduct index table as an instrument for analysing the behaviour owf companies in South Kordofan (as seen in Chow and Wong-Boren 1987; Cooke 1989; Wallace and Naser 1996; Inchausti 1997; Depoers 2000). Following Maali, Casson and Napier (2003) each corporation was given a score of 1.0, 0.5, or 0.0 on each index item, depending on whether that item is present and disclosed in its performance reports, partially or unclearly present and disclosed, or not present or disclosed at all. The scoring was cross-checked during field interviews with company officials. For purposes of computing each company’s total score (CTS), the scores on each index item were simply added together, thus giving them equal weight. The effective conduct/index (ECI) for each index item was computed as the average of the scores of all the companies on that item. The optimal conduct/index (OCI) for each item is assumed to be 1; i.e., thorough conduct. Optimal CSR conduct as to each item is qualified by at least four attributes whenever possible.

As part of our study, we went through annual reports and websites where DCs disseminated information regarding their missions, visions, codes of conduct, and values. Below we mention some of them.

Bank of Khartoum, the largest Islamic bank offering its customers a portfolio of innovative financial products and services. The bank has committed itself to a CSR theme of “Giving Back in Action,” with the following mission statement: “Bank of Khartoum recognizes the importance of supporting the social development of Sudan through its Corporate and Social Responsibility (CSR) program. The contributions of the bank toward Sudanese people are a significant priority within the bank with a primary focus on initiatives which provide a direct benefit for the communities” (http://www.bankofkhartoum.com).

Saving & Social Development Bank, a pioneer, socially oriented bank, which is credited with bringing the social dimension element into Sudanese Islamic banking. Its mission statement, given at the very beginning of its annual report, states: “Deliver diversified financial services to the small producers across the Sudanese rural and urban community at a high quality and efficiency, aimed at alleviating poverty and unemployment and realizing financial sustainability” (Savings & Social Development Bank, Annual Report 2013, 2).

Shiekan Insurance and Re-Insurance declares that: “Our mission is to achieve higher revenue and benefits for policy holders and shareholders by providing products and services for insurance, competitive prices, and high professionalism to satisfy our customers and provide them with the finest and most distinguished levels of protection and security, standing by their side when needed” (www.shiekanins.sd).

Zain Communication Company Sudan, established in 1997, is one of the biggest mobile services providers. With a client base of more than 12 million, the company has approximately a 60% marketing share of the Sudanese communication market. On its website, the company states: “Zain Sudan has taken ‘community responsibility’ as a basic strategy for work and allocates an amount of money for supporting social services annually, in four pivotal areas: health, education, training and capacity building, and stewardship of the environment, across all Sudanese states” (www.sd.com).

Kamla draws attention to the fact that “insights from religion and theology can also contribute to the pursuit of social justice through enhancing spiritual aspects of accounting and finance” (Kamla 2009, 925). All ten companies started their annual reports by quoting Qur’ānic verses, particularly those related to the prohibition of ribā (banks and insurance corporations), fair distribution of wealth, and commitment to social justice (investment corporations).

CSR conduct

Community development

In light of their claims of social commitment, it seems fair to expect the companies to pay much attention to community-based engagement projects. In addition to donating charitable funds, they should also be involved in social impact investments (e.g., reformatory institutions, literacy projects, and provision of medical services to impoverished communities, etc.) and development impact investments (e.g., infrastructural development projects). Carrying out such projects might help to realize social justice and economic equality among the disadvantaged communities. This could either be done via direct financial support or indirect support like sponsorship of events that enhance public interest. DCs are supposed to show commitment that is oriented for the social betterment of the local communities. The benchmark index examines four areas:

- Contributions to social development projects;

- Contributions to addressing social problems;

- Types of projects supported; and

- Amount of funds spent.

The average score on this item is only 0.2. DCs in South Kordofan pay only scant attention to issues related to community development. Only three corporations gave some support to community development projects: SSDB (0.5), BCI (0.5), and GNPC (1.0). According to its performance report and facts on the ground, GNPC did much along the oil pipeline from Kailk Lake up to Karkaraya Station, South Dilling Locality. Most of their contributions were in the fields of water supply, education, and health. The rest of the corporations (70%) scored zero. This clearly indicates that community development has not been an issue of concern in their business agendas.

Payment of zakat

Zakāt is the only one of the five pillars of Islam that has a direct economic dimension. It is an obligatory transfer of wealth by the rich to the poor, its main objective being to provide financial support to specific categories of people such as the poor and the needy. As the only pillar with an explicitly economic objective, zakāt is “accorded a prominent place in contemporary writings on the Islamic economic system” (Kuran 1986, 143). It is considered to be a central, if not the only, component of fiscal policy. Throughout the history of Islam, zakāt has existed as a well-organized system, automatically distributing wealth among the poor, the handicapped, unemployed, dependents of prisoners, orphans, and travellers in need (Shirazi 1996; Kuran 1986). The claim by Islamic business institutions that they are entities with a social agenda depends in large part on their paying their annual share of zakāt. DCs working under Islamic-based economies like Sudan are required to pay their zakāt on behalf of their shareholders if any of the following three conditions exist: if a resolution to such effect is passed by the shareholders in their annual general meeting; if payment is clearly stipulated in their charter of association; or if the law requires them to pay. In Sudan, all companies are required by law to pay zakāt at the end of each fiscal year. It is levied at a 2.5% rate on investment undertakings.

Since zakāt has social and economic impacts on the community, the following aspects are investigated:

- The actual payment of zakāt;

- Statement of the amount and sources of the fund;

- Statement indicating the fields in which it has been used; and

- Computation and distribution of the fund.

In terms of this index, the performance of the 10 corporations is ambiguous. The ECI of zakat payment and distribution is only 0.25 on average. Out of 10 corporations, five (BOK, SSDB, ZCC, MTN, SIC) paid their zakat, whereas the other five (SCI, BCI, GNPC, ATC, DTC) did not. Ambiguity arises from the fact that the five corporations that pay zakat are not authorised to use it locally and as they see fit. According to all the interviewees, it is an issue decided in Khartoum with no consideration to the views of the corporations themselves.

Employment opportunity

Today, any DC is supposed to be committed to paying attention to the local community in designing and implementing its employment policy. Local people are to be given priority when there are new job opportunities, at least at the bottom level. Another mechanism that is supposed to prioritize the rights of the locals is for the corporations to create new employment opportunities to absorb members of the local communities according to their available knowledge and qualifications. The benchmark index treats this item in terms of:

- Availability of the quota in employment;

- Number of the employees recruited;

- Leadership positions; and

- Newly created jobs.

Results showed that, based on this index, businesses achieved one of their two highest scores (0.35); however, still low and not consistent with the claims of employment policies tailored to local communities. Field interviews and observations revealed that employment policies are centrally designed, regardless of location. Outsiders occupy most of the leadership positions. The recruitment of the locals is primarily based on the calculation that their employment comes at little to no cost to the business, in terms of living or transportation costs.

Philanthropic donations (charity)

In general, Islamic voluntary alms are given on charitable grounds. This is meant to bridge the gap where the collected value of zakāt does not cover the current needs of the community. The Qur’ān and the Sunna advocate for charity, urging wealthy Muslims to give. Those who do, in addition to paying the compulsory zakāt, are promised they’ll go to Paradise (Qur’ān 2:271). Sudanese Islamic scholars consider charity as another means at the disposal of DCs, besides zakāt, for combating poverty and alleviating economic misery. The community and the stakeholders of the corporations should know that they are not driven only by economic objectives. They must show that they are willing to contribute to the well-being of the community via charitable donations. Our benchmark index covers four elements of conduct/disclosure requirements related to charity:

- Sources from which the fund was derived;

- The amounts given out;

- Purposes for which the funds were given; and

- Names of the beneficiaries (individuals/institutions).

Although charitable donations are highly praised by Islam, the ECI is quite low: only 0.10. Out of the 10 corporations, only two (SDB and GNPC) allotted resources for philanthropic purposes, whereas eight showed no sign of charitable donations. None of the corporations satisfied more than half of the benchmark’s requirements. Surprisingly, the two corporations that did make charitable donations placed them under the heading of tabrruat, which means “donations,” without any further details provided. Some of the corporations indicated that they gave their charities upon the direction of governmental entities and to support government activities.

Economic development

The famous historian of economic development, Joseph Schumpeter, regarded the DCs and entrepreneurship as being two key agents in the whole process of development (Iqbal 2002, 115). The business (investment firms, banks, insurance companies) is identified as the main mechanism through which scarce capital sources are gathered, multiplied through circulation, and channelled to their most productive and entrepreneurial uses in the economy. DCs facilitate the dynamics of the development process by which economic welfare of the local community can be achieved. Many tools are at the disposal of DCs to enhance economic development. Poverty alleviation strategies through micro-finance initiatives and other programs are the most known. Our benchmark index covers four elements on this point:

- Possession of capital assets;

- Funding income-generating activities via micro-finance;

- Amount of funds allocated; and

- Other micro-investment programs,

Results for this index are striking, with an ECI of only 0.1. With the exception of two corporations (BCI and GNPC), none have shown any level of commitment with regard to this index. In their response, eight corporations indicated that the security hazard was hindering any further involvement. Many of them argued that they are not charitable entities, but instead work to maximize profit in a very uncertain and risky environment. Thus, they are not expected to jeopardize their business and go beyond their mandate.

Building infrastructure

Infrastructures include roads, bridges, water supply, sewers, electrical grids, telecommunications; viewed as creating physical components of interrelated systems providing commodities and services essential to enable, sustain, or enhance societal living conditions. Over the last decade, governments around the world pursued policies to involve the private sector in the delivery and financing of infrastructure services. Investment companies should spearhead such initiatives; first, to enhance their own production capacity; second, for demonstrating that they are good investment institutions. Our benchmark lists the components of this index as:

- Contribution to building roads and highway networks (bridges, tunnels, culverts, retaining walls), road maintenance, airports;

- Electrical power networks, generation plants and communication systems;

- Potable water supply, sewage collection and disposal of waste water; and

- Governance infrastructure (law enforcement, provision of emergency services, and training facilities).

Similarly to other scores, the average ECI of the infrastructure index proved to be poor, only 0.15. Apart from three corporations (BCI: 0.5, MTN: 0.5, GNPC: 0.5), none of the others showed any commitment. In fact, the managers of those seven corporations believe that the actions connected to this index do not fall within their responsibilities; rather they identified them as being part of the government’s duty.

Ethical business

Generally, DCs should adhere to the range of morals and values of the society in which they operate when they offer their services. From an Islamic point of view, business transactions can never be dissociated from the moral objectives of the society (Farook and Lanis 2007, 218). Business transactions must always be in accordance with the morals and values of the local community. They must seek social justice by foreswearing all forms of economic activity that are morally or socially harmful; they must ensure legitimate ownership of wealth; and they must seek to prevent the accumulation of wealth in a few hands. Basically, they must abstain from any activity that may jeopardize or go against the society’s norms and traditions. The benchmark index specifies four areas of ethical business:

- Transactions in accordance with the societal norms and values;

- Abstention from activities which harm societies;

- Removal of negative business impact; and

- Reward for land dispossession.

The average ECI on the ethical business index is 0.35, which is one of the best two scores. Seven corporations out of ten expressed clearly in their code of conduct, mission and vision statements that they are following the norms and values of the communities. Their spokespeople said that they usually refrain from indulging in any activity that may pose harm to local communities. They also expressed readiness to remove any negative societal effects caused by their investments. The remaining three corporations have done nothing so far to obtain a higher ethical business index. Compensation for disposition of land was mentioned only by GNPC, which reportedly compensated those whose lands were confiscated for the sake of the company. However, the person in charge at GNPC confessed that such compensation did not measure up to the aspirations and the real value of the land, yet, local farmers had to accept it.

Gender balance

Bias against women is no longer acceptable in the world of business. In conducting their business, DCs are advised to embrace gender equality and avoid socioeconomic measures that are biased against women. Specifically, the gender balance in business addresses the under-representation of women in management positions in companies, both private and publicly owned. Our benchmark index examines four points:

- Women’s positions of responsibility in the corporations;

- Quotas as an instrument to promote women in corporations’ boardrooms;

- Gender-oriented programs; and

- Amount of resources allocated for gender support.

For this index, the result is a 0.0 ECI. Gender and its related issues have never been a point of concern in any of the 10 corporations’ policies and programs. Women are not in any position of responsibility. The reason behind this position is the belief that women are treated equally, and not given any preference, when competing with men. Not one of the 10 firms has a gender-oriented program or policy.

Peace building

The ongoing war in South Kordofan has driven the whole area into unprecedented social rupture and caused much suffering. Without a macro approach to healing this social misery, any development efforts will be in vain. The expectation, therefore, is that companies allocate resources to this purpose. Commitment can be shown through support to those who have been directly affected by the war, IDPs and injured persons being two obvious beneficiaries of such programs. Our benchmark index covers four elements of conduct requirements related to peace building.

- Corporations’ contribution in addressing IDP needs;

- Corporations’ contribution in addressing DDR programs;

- Policies designed; and

- Amount of funds allocated.

There is a low average score of 0.1 on this index. Only two corporations (SDB and MTN) have policies and programs designed to support peace building. The rest of the firms confessed that such issues are not on their agenda at all. Most of them consider that this area has been monopolized by NGOs for many years. It is not their concern as they see it: “Our work is for business and peace building is not our business; it is a territory that has been occupied by NGOs for decades, and cannot be penetrated by outsiders” (BOK, SCI, BCI, ZCC, SIC, GNPC, DTC, and ATC). They also argue that any peace-building intervention can only be done per the government’s request or with its consent.

Environmental advocacy

Another key domain of social responsibility is environmental advocacy. It is internationally recognized that businesses have a role to play in preserving and advocating for the environment. For many years organizations got rid of their waste products by discharging them into the air, into rivers and on land. Acid rain, global warming, depletion of the ozone layer, and poisoning of the food chain, all resulted from irresponsible behaviour. Because of the work of environmental activists, firms have been obliged to recognize that maximizing profits should not be done at the cost of the ecosystem. Advocating for environmental issues can take the form of providing advisory services to educational information sessions and workshops, funding environmentally related research and supporting environmental activists. Environmental advocacy by businesses means an ongoing engagement in meaningful dialogue on environmental issues with different sets of stakeholders.

Four specific points are covered:

- Proactive policies related to environmental protection;

- Allocation of resources for environmental purposes;

- Purposes for which funds are provided; and

- Pro-environmental activities/projects financed, if any.

The ECI for environment advocacy is 0.0. None of the 10 corporations showed any concern about the environment. This indicates that environmental issues carry practically no weight in the firms’ decision-making. This is an unexpected result for Islamic businesses, at a time when the environment has become a top priority both for Islam and for contemporary CSR studies, which stress the need to preserve, protect and sustain. These concepts were found to be of no significance for the DCs working in SKS.

Concluding remarks

DCs working under an Islamic-based economy, like that of Sudan, are supposed to work differently from their secular, capitalist counterparts. The aim of this study has been to determine whether there is convergence or divergence between the theoretical norms of Islamic business and the practical experience of DCs in SKS.

The general result of the study indicates that there is a big gap between the ideals advocated by the companies in South Kordofan State and their actual performance. The disappointing performance is manifested in their low ECI scores on the ten indexes selected for our study.

There is also a wide divergence and incongruence between the firms’ practices and the codes of ethics and values they communicate in their mission and vision statements, such as “commitment to society” and “socially-driven, with an ultimate role which breaks through the profit maximization objective.” The findings of this study show that the firms are falling far below the expectations set out in such self-promotional statements. If they were truly committed to their objectives, these firms would be more favourable to thorough computation and management of their annual zakāt (ECI: 0.25), more motivated towards community development issues (ECI: 0.2), and keen on contributing to economic development projects (ECI: 0.1). In addition, they would be charitable and not only channel money towards those causes influenced by their political bias (ECI: 0.10). Being philanthropic is perceived as the highest level of responsibility of a business, after economic, legal and ethical responsibilities have been met (Gitman and McDaniel 2002, 110). These are the kinds of activities through which companies might show accountability not only to their stakeholders, but also to the community in which they operate. A degree of divergence was found among the firms concerning computation and payment of zakāt. Different firms apparently compute it in different ways, while some do not pay it at all.

A main obstacle is the mentality of the firms’ managers. Maximization of profit remains their sole driving force, never the ethical-religious or socioeconomic factors. The disadvantaged in society do not concern them. Terms like “poverty eradication” or “combating poverty” were rarely used in any of the firms’ annual reports, reports of social performance or on their websites. The clearest example of this profit-oriented nature is seen in the mission statement of Shiekan Insurance and Reinsurance (SIR), which was mentioned earlier. “Achieving higher revenue and benefits for policy-holders and shareholders” are the main objectives of the company. In short, the declarations of strong commitment to socio-economic objectives are a mere window-dressing.

The environmental advocacy ECI for DCs in SKS (0.0) was disappointing, to say the least. It represents another sign of the detachment of the firms from their proclaimed goals and expected role. Environmental concerns do not seem to be part of the DCs’ agendas. We did not find evidence of any dedicated quotas or programmes to reduce their environmental impacts or support issues of environmental concern.

The study has shown that DCs in SKS portray themselves as committed to Islamic teachings and ideals and distinguish themselves from conventional corporations on social and ethical grounds. The statements and reports are tools they use in convincing their stakeholders that this is the case, including verses from the Qur’ān and passages from hadith literature, adding a spiritual dimension to their image. In reality, the corporations fail to meet the needs of the poor. Similarly to many recent studies on CSR for firms working under Islamic economies, the conclusion of this study is that the reality in South Kordofan is not consistent with societal expectations.

References

Carroll, A. B. 1979. “A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social responsibility performance.” Academy of Management Review, vol. 4, no. 4: 497–505.

Chow, Chee W., and Wong-Boren, A. 1987. “Voluntary financial disclosure by Mexivan corporations.” Accounting review, 533–541.

Cooke, Terry E. 1989. “Voluntary corporate disclosures by Swedish companies.” Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting 1, no. 2: 171–195.

Depoers, F. 2000. “A cost benefit study of voluntary disclosure: Some empirical evidence from French listed companies.” European Accounting Review 9, no. 2: 245–263.

Farook, S., and Roman, L. 2007 “Banking on Islam? Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure.” In M. Iqbal, S.S. Ali, and D. Muljawan (eds.), Advances in Islamic Economic and Finance. Islamic Research and Training Institute: Islamic Development Bank. Jeddah: Saudi Arabia, 217–247.

Gitman, L. J. and McDaniel, C. 2002. The best of the future of business. Ohio: South Western Publishing.

Inchausti, B.G. 1997. “The influence of company characteristics and accounting regulation on information disclosed by Spanish firms.” European Accounting Review 6, no. 1: 45–68.

Iqbal, M. 2002. Islamic Economic Institutions and Elimination of Poverty. Leicester, UK: The Islamic Foundation.

Kamla, R. 2009. “Critical insights into contemporary Islamic accounting.” Critical Perspective on Accounting, 20(8): 921–932.

Kuran, T. 1986. “The economic system in contemporary Islamic thought: Interpretation and assessment.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 18, no. 02.

Maali, B., Casson, B., and Napier, C. 2003. “Social Reporting by Islamic Banks: Discussion Paper in Accounting and Finance.” No. AF03-13, ISSN 1356-3548. University of Southampton: Southampton.

Shirazi, N.S. 1996. “Targeting, Coverage and Contribution of zakat to Households’ Income”, Journal of Economic Cooperation Among Islamic Countries, Vol. 17, no. 3–4, 165–186.

Wallace, R.O, and Naser, K. 1996. “Firm-specific determinants of the comprehensiveness of mandatory disclosure in the corporate annual reports of firms listed on the stock exchange of Hong Kong.” Journal of Accounting and Public policy, 14(4): 311–368.

List of Interviews

Interview, Abdamunim Kabaj, Dawa Transportation Company, Kadugli, 28 September 2014.

Interview, Alias, Bank of Khartoum, Kadugli, 20 September 2014.

Interview, Arjoon Transportation Company, Kadugli, 20 September 2014.

Interview, Ibrahim, Yagoub, Sudatel, Kadugli, 28 September 2014.

Interview, Jalal, Juli, Savings and Social Development Bank, Kadugli, 20 September 2014.

Interview, Mohammad, Elshaikh, MTN, Kadugli, 28 September 2014.

Interview, Mahmood, F. A., Shiekan Insurance and Reinsurance, Kadugli, 28 September 2014.

Interview, Salih, T, Greater Nile Petroleum Company, Karkaraya, 22 October 2014.

Interview, Sharif, Mohammad, Sawaed Creding Institution, Kadugli, 28 September 2014.

Interview, Moh, Alza3im, ex-mechanized Farmer, Dilling, 30 October 2014.