The Gatekeepers: Political Participation of Women in Malawi

How to cite this publication:

Happy Mickson Kayuni, Kondwani Farai Chikadza (2016). The Gatekeepers: Political Participation of Women in Malawi. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 12)

All over the world, there are gatekeepers with the power to facilitate – or restrict – peoples’ access. We have studied the role of the chairpersons and secretaries of the political parties in Malawi, and their role as gatekeepers for women’s access to political positions. These gatekeepers are largely determining their entry into elected positions and into positions within the party hierarchy, and for many reasons they tend to restrict women’s participation in politics.

Authors

Happy Mickson Kayuni

Associate Professor, Department of Political and Administrative Studies (PAS), Chancellor College,

University of Malawi

Kondwani Farai Chikadza

Lecturer, Department of Political and Administrative Studies (PAS), Chancellor College, University of Malawi

We have studied the supply side of women political participation and activism, and identified some of the factors that explain why women decide to run (or not) for political office. In our study on what makes women participate in local politics in Malawi, on what makes women volunteer to stand for elections and seek positions within party structures, we have found that it is partly due to support from spouses and traditional and religious leaders, plus exposure to development projects, NGOs, and local government institutions. The gatekeepers within the parties, however, the people with power within a party, can determine, for the most part, women’s entry into politics.

There is a growing interest in factors that contribute to women’s political participation both at the national and the grassroots level. We have studied why women become interested in party politics at the local level in Malawi.

The background research is a study we carried out in Mangochi, Chiradzulu and Phalombe districts of Malawi, on the four major political parties (the Democratic Progressive Party DPP, the People’s Party PP, the United Democratic Front UDF and the Malawi Congress Party MCP), in 2015. Key informant interviews were conducted with selected female candidates (for the position of councillor and MP in 2014), senior party officials, and female committee members of the four political parties.

In line with normative theories of democracy, our basic premise is that women are equal citizens and should, therefore, participate in politics on equal terms with men. However, in almost every country and locality, there are fewer women in elected positions and fewer women who are active in party politics than men.

The Role of the Political Parties

The political science and policy literature have debated lively the significance of political parties as strategic mediums for the promotion of women participation in politics. The “school of democracy” argument holds that by exposing citizens to politics, political parties are critical players in the socialization, recruitment, nomination, and election of candidates to public office, and in conveying the principles of democratic procedure. The importance of the political parties is rooted in the fact that access to political power and decision-making typically begins at the political party level. The expectations are even higher in multiparty democratic environments, where contesting parties represent multiple avenues for participation and representation of the hitherto marginalized segments of society, including, but not limited to, women.

Despite Malawi’s transition to a multiparty democracy in the early 90s, the political parties are still largely a masculine domain, with only a small minority of women represented. For instance, there are currently only 13.4 per cent women in the local councils elected in 2014.

The dynamics between women’s capabilities and ambitions on the one hand, and the political will and political power of the ‘gatekeepers’ of the political parties on the other, determine the extent to which women can participate in political parties and local politics. The gatekeepers are, in this case, influential individuals within the parties who can influence the decisions as to which party members should occupy contested positions at the local, regional, and even national level. They determine who will be elected or nominated to positions within the party, and they are influential in determining who will stand for the party’s ticket for general elections.

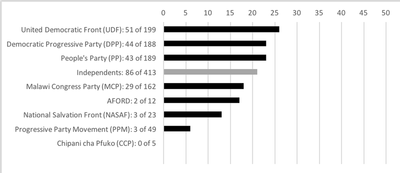

Malawi has a long history of male domination in politics. Men usually enjoy privileged access to the necessary material and political resources, even in traditionally matrimonial communities. Male domination in politics means that fewer women have been able to reach positions of decision-making within the political parties, and that women are nominated by the major parties in fewer numbers than men. Figure 1 illustrates this well. It shows how many women the parties nominated to stand for election in the 2014 parliamentary elections. (In absolute numbers and in relative terms with the horizontal bars).

Figure 1: Women candidates, 2014 parliamentary elections

Source: Chikadza in Amundsen and Kayuni (forthcoming 2016).

Figures in per cent, per party.

This table clearly demonstrates that women were underrepresented in the race, way before the votes were cast. If we are to judge the commitment of the political parties to the cause of equal political participation for women, based on the relative number of women candidates presented by the parties, the commitment is not impressive. Malawian political parties have indeed some ground to cover.

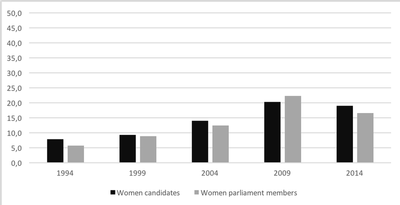

If the parties nominate more women candidates, this will (probably) translate into a higher number of women elected. This is because the voters largely elect the percentage of women that the political parties present (with only some small deviations). This is very clear from Figure 2, which shows the number of women candidates and the number of women elected from 1994 to 2014.

Figure 2: Trends in women candidates and women elected

Source: Mesikano-Malonda in Amundsen and Kayuni (forthcoming 2016).

Figures in per cent.

The table shows that in Malawi, the number of women candidates and the number of elected women are closely related, and this means that a higher number of women candidates, presented by the parties, in general leads to a higher number of women elected. The table also shows that women get only a slightly smaller percentage of votes compared to the party nominations. The only exception was the 2009 election when women received more votes compared to party nominations. We also note that despite a steady growth in the percentage of women presented, the 2014 elections was a setback.

Thus, the parties are the most important ‘gatekeepers’ and will have to nominate more women if the numbers are to approach equality, a promise made over and over again by various political leaders.

The Role of the Political Party Gatekeepers

The political parties and their ‘gatekeepers’ are critical to get more women into politics. In our study, we identified the party chairperson and the party general secretary as the main gatekeepers at the local level, and we found that support from political parties, through their respective gatekeepers, was a major factor in determining women’s entry into politics.

The gatekeepers may promote as well as hinder candidature. If the chairperson or secretary general supports a particular candidate, that candidate is likely to be endorsed by the party. Thus, once they were identified, the chairperson and secretary played an advisory and moral support role for the candidate, and they also mobilized support for the candidate and ‘sold’ the candidate on behalf of the party. Without this endorsement, it is hardly possible for candidates to win party primaries for elected public office, let alone get a position within the party hierarchy.

According to our interviews with candidates as well as with party officials, the gatekeepers will normally support and promote individuals who are like themselves, and consequently, because there are few women gatekeepers, women tend to end up being side-lined. In other words, if there were more women gatekeepers, it is likely that they would promote more women.

We also found that the political party gatekeepers will support women candidature to party positions when they want to support the party structures at the grassroots level. In interviews with several secretaries of the political parties at district level, we found that gatekeeper support for women was high in many cases, but this was for women representation in non-important positions within the party.

Firstly, women often spearhead the party with dances and through mobilizing supporters. One senior PP official said that what “is a political party without the women and their dances?’’ In this regard, women help by inviting others to join the party, especially during the campaign period. Their singing is perceived as boosting the morale of the party.

“What is a political party without the women and their dances?”

Collage pictures by Govati Nyerinda 1 2, Gilbert Sauti 3, Lise Rakner 4

Women members also facilitate logistical issues related to organising party meetings such as welcoming visitors. More importantly, they help bring more support by attracting their fellow women to the party. According to one of the gatekeepers, “women articulate the merits of the party much better than men”.

At the same time, the party gatekeepers were less interested in promoting women candidates for contested elected public positions like MPs and district and local councillors. The criteria for gatekeeper support for the different candidates is usually their “electability”, and this is largely based on the candidate’s economic status.

Economic strength is considered important by the party gatekeepers as well as the voters. A candidate stands stronger who has adequate funds for a campaign and for handouts, and who will not financially squeeze the party. Consequently, this disfavours women because they do not have the necessary financial resources. In fact, when analysing the socio-economic status of the nominated and elected female candidates (for MP and councillor positions), we found that the majority of them had stable businesses, independent livelihoods, and/or rather well-to-do spouses. As one female committee member of MCP in Phalombe mentioned,

People have too much love for money. No one can win without money. People have no problem with women and all they want is material and financial support.

One senior DPP party official in Chiradzulu provided another example that shows how much economic status matters. He said that the DPP campaigned strongly for their female candidate, Dr Mbilizi, and that the DPP was the most popular party in the whole district so according to him the elections were just a matter of formality. Dr Mbilizi was posed to win. However, a little known male independent candidate, Mahomed Osman (who was not originally from Chiradzulu, but a Malawian of Asian origin), managed to win the elections. The general view was that Mr Osman won because he was good at giving handouts, such as blankets and bicycles, and he had sunk numerous bore-holes in Chiradzulu. Thus, although the DPP candidate was endorsed by the party gatekeepers because she was perceived to be economically strong (the main criterion, in addition to being well educated), the independent candidate proved to be economically stronger, and he won with a good margin.

Next to financial means, the gatekeepers we interviewed mentioned the candidates’ popularity. The the elections in 2014 was not a good time to endorse too many female candidates. This was because of the bad legacy of the out-going female president; many voters were demotivated by the performance of incumbent President Joyce Banda, among other things because of the so-called ‘cashgate’ corruption scandal that emerged during her presidency. Many were also demotivated by what was perceived as the bad performance of some female MPs. In Chiradzulu, for instance, the chairperson of the DPP mentioned that the party had nominated three women in 2009, but they had disappointed the people with their arrogance and with ‘power gone to their heads’.

Thirdly, our interviewees mentioned that due to cultural norms, very few women are assertive. Allegedly, they lack confidence, and this is exploited by their male rivals. According to the gatekeepers, the cultural attitudes, which expect women to obey their men, extend into the political parties, where most women remain virtually quiet. Often, they wait for men to lead the way, and men look down on women’s capacity. As one government official in Phalombe mentioned: “Culture has condemned a woman to the kitchen, child bearing, and washing household utensils”.

The Legal Framework

Although a legally enforceable legislation has proved to be an asset elsewhere, for instance legislation that compels political parties to field a minimum number of women in parliamentary elections, the legal instruments governing elections and political parties in Malawi, do not provide for such affirmative action. Legislation does not protect, let alone promote women participation in party leadership and general elections.

As a result, the political parties in the country are at liberty to field candidates of their choice, regardless of gender considerations. While this is not a vice in its own right, the implication is that male candidates usually dominate the nomination lists of the key political parties, due to their superior positions of political as well as financial power. Women have to be better educated, more exposed to politics, financially affluent, and (most importantly) better connected to the top leadership of the respective political parties to get a nomination. The following interview excerpt illustrate this point:

Political parties do not just choose parliamentary candidates anyhow. We have to choose people who are appealing to the electorate. They have to be educated, financially stable, with some working experience elsewhere. Unfortunately, in this district, most of our women do not have these attributes and they lack the confidence to convince us even at primaries (PP Constituency Governor, Mangochi).

However, activism and personalities have in some instances challenged these established (formal and informal) rules of the game. For instance, at the local level of the party structures (branch and district committees), there is a good balance between men and women (and youth) represented within most political parties’ organisations at the local level, at the same time as women are disproportionally represented in elected political positions and within the parties’ leadership structures. A careful appraisal of the political party constitutions and practices demonstrates that voluntary quotas exist and are observed in the recruitment of party leaders in grassroots structures. We have found, for instance, that UDF has an equal representation of men and women in all committees from the Branch level to the District Executive Committee level, and this also applies to the DPP and the MCP. Thus, we can conclude that there are formal institutional arrangements, created by the party elites, which promote gender equality at the grassroots level.

From the Regional Executive Committee level to the National Executive Committees, however, these gender considerations tend to fall off. Unsurprisingly, membership in these top party structures is dominated by men, because of their privileged political, economic and human capital. The following interview excerpts illustrate this well:

At the Regional and National Executive Committee levels, we do not consider gender equality because at those levels we are interested in individuals who are educated, experienced, and those who have been exposed to politics in different countries. So, we don’t normally consider gender. For one to reach those levels it requires demonstrating one’s capabilities. Nonetheless, we have a few women even at the National Executive Committee (UDF District Governess, Mangochi).

At the National Governing Council level, individuals are elected into positions at a national convention based on their competencies regardless of their sex. They have to be appealing based on their levels of education and experience in politics. Some are appointed by the elected party leaders. The idea is to make sure that only genuine members of the party hold key positions, for fear of ‘selling’ the parties to ‘aliens’ (DPP District Governor, Phalombe).

In sum, we can conclude that there are some mechanisms (even formal rules) that promotes equal representation at the lower levels, at the same time as there are other (informal) rules and mechanisms that ensure male domination at the higher levels of the political parties. Women representation at the lower level is mainly ‘symbolic’: the political parties engage women in singing, dancing, and praising, but the top level of party politics is a masculine domain.

Policy Options

Legal instruments and affirmative action is one possible option to enhance women representation in politics in Malawi. However, even when we know that the formal institutional arrangements and legal obligations will have an effect on women participation, we should not forget that formal and informal rules are deliberately created and enforced, largely by the political gatekeepers.

We will therefore argue against an indiscriminate adoption of the popular line of thought that asserts that the institutional environment of the big political parties is unfavourable to women participation. As demonstrated, the formal rules of the game that regulates participation of women range from the indifferent to the rather promotive. We have seen there are formal institutional arrangements, created by the party elites, which promote gender equality at the grassroots level, but at the same time, informal rules and their application by the party gatekeepers, tend to restrict women’s entry into more powerful positions.

When the formal rules and institutions have made some inroads to gender equality, notably in terms of equal representation in local party structures, we have also seen that informal rules then emerge and supersede the formal ones when decisions and made on who can participate, at what level, and how. The formal and informal institutional mechanisms, internal to the key political parties, are all products of political deliberations, made by the political gatekeepers.

We have identified the party gatekeepers as decisive. Consequently, there is a need for more attention on identifying these gatekeepers, their origin and specific role. We have mentioned that more women gatekeepers are likely to promote more women, but more needs to be done to positively influence the gatekeepers to be more gender sensitive in their decision-making.