Civilians’ Survival Strategies amid Institutionalized Insecurity and Violence in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan

2. The Nuba Mountains: Geography, History, and Violence

3. Institutionalized Insecurity and Perpetual Violence: Historical Account

4. Postcolonial Marginalization, Institutionalized Insecurity, and Nuba Peaceful Struggle

5. Shifting from a Peaceful to a Violent Political Movement: The First War 1985–2005

6. Renewed War and Civilians’ Responses in the “Killing Fields”

How to cite this publication:

Guma Kunda Komey (2016). Civilians’ Survival Strategies amid Institutionalized Insecurity and Violence in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (Sudan Working Paper SWP 2016:4)

1. Introduction

Recent literature indicates that wars in different parts of the world have changed radically since the early 20th century, to the point where some 80–90% of war victims are now civilians (Human Security Centre 2005; Wood 2008; Bellal 2014). Today, war-torn Sudan, with prolonged and recurring violent conflicts in Darfur, the Nuba Mountains and southern Sudan, showcases that change. Sudan’s civilian causalities are unprecedented. Sudan territories have in fact been recently described as Killing Fields associated with political violence and fragmentation (Beny and Halle 2015).

Key Argument

The Nuba’s peripheral homeland of the Nuba Mountains, in southern Kordofan, is one of Sudan’s current killing fields, with high numbers of civilian casualties, of wounded and internally displaced persons, refugees, families, and individuals. One key overarching argument framing this paper is that the recurring and prolonged wars in Sudan are better understood when put in a wider precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial historical context of the Sudanese socio-political historiography. Thus, it is argued here that the present excessive violence in Sudan in general, and in the Nuba Mountains in particular, is essentially a result of institutionalized insecurity prevalent throughout the precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial history of the Sudanese state.

The wide range of literature covering different political episodes in Sudan supports this assertion. It succinctly confirms the continuity of institutionalized insecurity and perpetual violence from the precolonial kingdoms (MacMichael 1922/67, 8; Spaulding 1987, 372); the Turco-Egyptian rule and its slave trade institutions (Pallme 1844, 307–324; Lloyd 1908, 55; Trimingham 1949, 244), the Mahdist’s brutal Jihaddiya of forced militarization (Sagar 1922, 140–141; Trimingham 1949, 29; Salih 1982, 37); the colonial closed district policy coupled with brutal punitive operations (Gillan 1930, 1931; Roden 1975, 298), the postcolonial violence and protracted civil wars generated by the state against its own citizens at the peripheries (Deng 1995; Johnson 2006; James 2007; de Waal 2007; Manger 2007; Komey 2010a, Komey 2013b; Ahmed and Sørbø 2013).

Focal Questions and Objectives

In light of the above, the aim is to trace institutionalized insecurity and perpetual violence in the Nuba Mountains and their impact on civilians in the war zone. Though it starts with an historical, analytical overview, the focus of the paper is to describe the circumstances civilians found themselves in amid violence in combat zones of the Nuba Mountains during the first and the second wars of 1986–2005 and 2011–. It traces the physical survival, the economic and cultural resilience adopted by war-affected communities and individuals in an environment of extremely high and sustained risk and insecurity during the first war (1983–2005), as well as during the second war, which erupted in 2011 and continues unabated.

The analysis of civilian self-protection through different coping and survival mechanisms during wars is important for a number of reasons, not least because of the duration and recurrence of wars, the lack of international assistance, the remarkable levels of self-reliance demonstrated by people facing extreme hardships, and the variation of human insecurity experienced by civilians in a situation mounted with high risk. Hence, two burning questions arise: What are the survival strategies or coping mechanisms deployed by the Nuba at different stages of the imposed perpetual violence and institutionalized insecurity? How effective are those strategies and mechanisms for their physical and cultural survival?

To examine these two key questions, different types of secondary data are utilized. Data includes recent publications and reports from the field, and my own observations resulting from a sustained intellectual engagement in, and following of, most of the key events in the region.

Following this introduction, part two of the paper presents the Nuba Mountains/South Kordofan as a social space and reflects on its geographic and historical dynamics. Part three instead provides a brief account of the precolonial and colonial forms of institutionalized insecurity and violence imposed on the Nuba people. Part four gives analytical details on the postcolonial institutionalized insecurity and state-driven violence, and Nuba responses through peaceful political movement during the 1960s and 1970s. The Nuba political shift from peaceful to armed struggle and the emergence of the first war in the Nuba Mountains is the subject of part five. Part six deals with the second war in the region with focus on war dynamics, intensity, and civilian responsive mechanisms deployed to physically, culturally and economically survive the killing fields. A brief summary of the overall discussion and findings concludes the paper.

2. The Nuba Mountains: Geography, History, and Violence

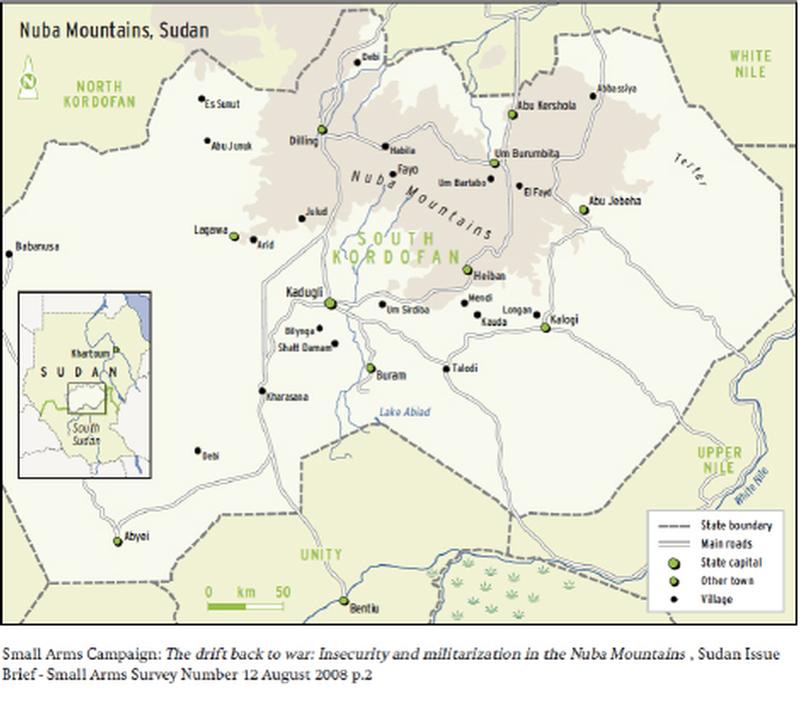

Before the separation of South Sudan in 2011, the Nuba Mountains region, which represents the greater portion of southern Kordofan, was located in the geographical centre of the former undivided Sudan, and covered an area of approximately 88 000 km² within the savannah summer belt (see Map 1). Following the separation of South Sudan, the relative location of the Nuba Mountains changed from central to borderland. This “new” relative location has situated the region in a unique and significant geopolitical position along the north–south divide. As an emerging borderland, it shares an international border with South Sudan. The entire international boundary between the two Sudans is some 2 010 km (1 250 miles) long, and the longest part of this north–south international boundary runs along the South Kordofan territory. Moreover, the region hosts most of the contentious, yet unresolved, issues between the two Sudans; namely, Abyei, oil, pastoral grazing zones and several disputed boundary points (Komey 2013a). At present, Abyei remains a highly disputed border area between Sudan and South Sudan associated with recurring different levels of clashes. As a result, the case was taken to Arbitration by a panel under the Permanent Court of Arbitration in Hague in 2008. At later stage, a hybrid AU-UN peacekeeping force was deployed which remains to present day awaiting final solution to be determined by a Referendum.

The Nuba people represent the majority of the population of South Kordofan, estimated to be around 2 508 000 persons. Nubas are a sedentary group of African origins. They embrace Islam, Christianity and some indigenous beliefs. The nomadic Baggara Arabs are the next largest group of people in South Kordofan. Of significant size are also the Jellaba traders from northern Sudan, who have strong links to state power and wealth, and the Fellata, originally migrants from West Africa.

The region is a promising agricultural zone and an economic base for the Sudanese agrarian economy. Since the 1960s, there has been a successive introduction of modern mechanized rain-fed farming in the region. The mechanized farming and trade businesses are controlled by the small but extremely influential groups of the Jellaba, from northern and central Sudan (Komey 2010a). Moreover, recently discovered fields rich in oil, have added more economic, political and strategic significance to the region. Despite the Nuba Mountains’ richness in natural and human resources, its salient features in precolonial, colonial and postcolonial history are economic underdevelopment, sociopolitical marginality, exclusion, and “institutionalized” violence (Mohamed and Fisher 2002; Johnson 2006; Komey 2010a, 2014).

Classic literature on Nuba historiography asserts that the Nuba people were the first to settle in greater Kordofan, thousands of years before any other group. They, therefore, identify as indigenous to the region (Lloyd 1908, 55; MacMichael 1912/67, 3, 197; Trimingham 1949/83, 6; Saavedra 1998, 225). Despite this, the Nuba were not incorporated into the Sudanese mainstream political culture, religion and social identity. As a distinctive, yet excluded, sub-national community, the Nuba and their region, the Nuba Mountains, exhibit three major features of contemporary Sudan: the African and Arab character of the diverse Sudanese society; the unequal and exploitative forms of centre–periphery relations within a broader socio-spatial system; the consequences of political marginality, distorted forms of development interventions by the state (Komey 2005, 2011; Ille, Komey, and Rottenburg 2015). Most importantly, they represent one of Sudan’s most bloody killing fields of the last three decades.

3. Institutionalized Insecurity and Perpetual Violence: Historical Account

Contemporary recurring conflicts and violence experienced in the Nuba Mountains in postcolonial Sudan are nothing but a replication of violent episodes experienced during the precolonial and colonial eras of Sudan. A brief review of those historical eras speaks to this assertion.

3.1 Precolonial Violence through Forced Relocation, Enslavement and the Jihadiyya

Literature covering the precolonial history of the Nuba demonstrates that when the Arabs started to conquer the northern part of Sudan, the Nuba were forced southwards, first into the plain areas of greater Kordofan. There, they enjoyed a period of relative tranquility and peace until they were forced to retreat further up into the mountains of southern Kordofan when the nomadic Baggara penetrated the Dar Nuba from the west in the 1780s (MacMichael 1912/67, 3; Trimingham 1949, 244). Upon their arrival, the Baggara Arabs began to raid the Nubas, enslaving everyone they could lay their hands on. In response, the Nuba retreated into their jebels (mountains) in remote areas. The severity of these raids resulted in wide-scale deterritorialization of the Nuba from their plains (Spaulding 1987). This early subjugation marked the beginning of the Nuba’s displacement and enslavement (see Pallme 1844; Lloyd 1908; MacMichael 1922/67; Spaulding 1987).

The Fung Kingdom rulers, the Jillaba, the Mahdiyya regime, foreign slave traders and the Turco-Egyptian rulers made things even harder (Komey 2010a, 35–38). In the middle of the 17th century, allied forces of the Fung Kingdom and local Arabs invaded Kordofan and brought further disorder and insecurity among the Nuba. The Nuba were forcibly pushed once again southwards and ended up occupying uninhabited jebels. From that time onwards, there were periodic raids. Some accessible Nuba hill communities were subjugated to Fung rule through two channels: the Sultan of Ghudiyat of Kordofan, and the vassal fiefdom of Tegali. By the middle of the 17th century, the kings of Tegali reigned supreme over northern-eastern Jebels. To the southwest, many Nuba hill communities were indirectly subjugated to Tegali, including the Kwalib, Alleira, Heiban, Shawai Nuba and possibly also the Otoro. One prominent historian reported that:

In the Nuba Mountains… the government imposed a system of coercive control that may be called “institutionalized insecurity.” The government itself raided the deviant or recalcitrant, and fomented hostilities among groups of subjects by exacting taxes in the form of slaves or livestock which could be obtained most easily, if not exclusively, by attacking one’s neighbors. Universal insecurity had the effect of making farmland politically scarce and stock raising precarious. These conditions favored a second major government policy, the diversion of labor away from agriculture to extractive activities such as washing of gold and the hunting of ivory, honey, and slaves. (Spaulding 1982, 372–73)

Such, roughly, was the state of the Nuba affairs when the whole of Sudan entered a new violent phase during the Turco-Egyptian rule (1821–1885). The process of Nuba enslavement and the dispossession of their land was reinforced and institutionalized during the Turco-Egyptian rule. The Turco-Egyptian rulers did not attempt to conquer the Nuba region, “but took tribute, at first in the form of slaves, for recruits from more accessible jebels such as Dilling, Ghulfan, Kadaru, and Kadugli. A few were also attacked and either reduced or wiped out” (Lloyd 1908, 55; Trimingham 1949, 244).

For several years, the Turks, Egyptians, and foreign and local traders raided these areas. For example, in 1824, four years after the conquest, the number of Nuba who had been taken into captivity was estimated at 40 000, but by 1839 the figure had reached 200 000. The Nuba captives were distributed as follows: the best men were recruited into the army, others were handed over to Turkish soldiers in lieu of pay, and all those remaining were sold at public auctions (Pallme 1844, 307, 324, 309; Salih 1982, 33–5).

Violence against the Nuba further escalated during the Mahdiya era, with far-reaching ramifications—territorially, socioeconomically and politically. At the outset, the Mahdiyya movement launched a direct and forcible mobilization of the Nuba into the Jihadiyya (the Mahdist armies) to support its troops in Omdurman (Sagar 1922, 140). In the process, it gathered a large number of recruits, mostly by force, often associated with mass atrocities. Even children did not escape the massacres “where they were seized by the feet and their brains dashed to pieces on the rock” (Wingate 1892: 98–9, quoted in Salih 1982, 37). The lucky ones were taken as captives, and there was a slave market in al-Obeid where women and children, mostly Nuba, were sold. Sometimes, the Mahdiyya would arm an allied group of the Baggara and instruct them to encamp at the foot of the Nuba jebels (Salih 1982, 38).

Towards the end of the Mahdiyya, and the beginning of the Anglo-Egyptian (colonial) rule, the state of the affairs in the Nuba Mountains was characterized by (1) wide-scale slave raids in the Nuba communities, all of which were associated with their subjugation, overlordship and suzerainty by local Baggara, slave traders and Tegali Kingdom rulers; (2) deterritorialization, mass devastation and permanent displacement of the Nuba from the fertile areas of their plains and, consequently, from their livelihoods following the repeated attacks and violent occupation of their homeland by others; and (3) subjugation by those whose centre of power was located elsewhere.

3.2: Colonial Punitive Operations and Forced Resettlement

Following the overthrow of the Khalifa in 1898, the Anglo-Egyptian administration found that the Nuba were still insecure due to some slave raiding by local Baggara. For example, “in November, 1902, a series of slave raiding cases carried out by the local Baggara on the Nuba was reported” (Komey 2010a, 37). Hence, the immediate challenge that faced the colonial administration was to put an end to the slave raiding and to eliminate local Baggara Arab suzerainty and overlordship. However, the colonial administration interpreted the spatial distribution of the Nuba on the top of the hills and the Baggara in the fertile land adjacent to those hills as a norm rather than as an anomaly brought about by a series of violent interventions and sustained institutionalized insecurity.

Given that their memories of the precolonial slavery and subjugation were very much alive, the Nuba resisted any direct contacts or cooperation with the colonial administration. Instead, they fortified on their hills. As a result, the colonial government carried out a series of policies against them, including (1) pacification campaigns among various defiant Nuba hill communities followed by forced down-migration; (2) the introduction of the Closed District Ordinance of 1922, and Gillan’s Nuba Policy of 1931; and (3) the introduction of cotton production in 1925 (Gillan 1930, 1931; Trimingham 1949).

In the process of pacification, several punitive operations were carried out against defiant Nuba hill communities. These punitive operations were atrocious, resulting in massive killings and destruction of the means of livelihood of the Nuba hill communities. Similar to the precolonial era, the government adopted a policy of institutionalized insecurity. It also mobilized the local Baggara to actively participate in these violent operations against the Nuba. For example, in the case of Patrol No. 32 against the Niyam Hills, 100 Baggara with their horses participated in the operation alongside government forces while attacking the Niyma Hills. Below, and as detailed elsewhere (Komey 2014, 19), is a brief list of some major punitive operations that resulted in massive violence and insecurity:

- Operations against the Agabna Aruga Mek of the Niyma Jebel 1917–1918;

- Operations against the El-Faki Mirawi Mek of Miri Jebels, 1915; and

- Operations against the people of Jebel Eliri 1929–1930.

The main objectives of these operations were to kill or capture the defiant Nuba leaders, to destroy crops and villages, to capture cattle, to capture all the young men and the leaders involved in the resistance and, consequently, to pacify the Nuba. In some inaccessible hills, the colonial government used planes to bombard those hiding in caves. Operations against Jebel El- Liri are an illustrative case. The punitive and pacification processes resulted partially in further movement of some defiant Nuba hill communities higher up into the hills, seeking protection. Ultimately, many, if not most, were forced out of their hiding places and back down into the valley. They were then “forcibly resettled in accessible valleys and lower slopes, ridges and foothills as part of the process of pacification, while others were gradually moving down voluntarily” (Komey 2014, 19).

Initially, the British were not in favour of allowing Arab culture and Islam to influence the Nuba’s cultural identity. That is exactly why they introduced the Closed District Ordinance of 1922, followed by Gillan’s Nuba Policy in 1931. Contrary to those policies, however, the introduction of cotton production in the region in 1925 had already strengthened daily contacts between the Nuba and the local Baggara and inevitably exposed the Nuba to Arab culture and Islam influences. Moreover, it accelerated the transfer of the Nuba land to more powerful newcomers, namely the Baggara, the Migrant Felata and the Jillaba merchants. In fact, the government failed miserably in empowering the Nuba economically, culturally or politically. Instead, it “stimulated the involvement of more powerful actors who presented a further threat to the powerless Nuba’s livelihood and survival” (Komey 2010a, 42).

Thus, by the time of the independence of Sudan in 1956, the communities of the region were highly stratified; the Jillaba, the Baggara and the Nuba essentially occupied the top, the middle and the bottom of the ladder vis-à-vis socioeconomic development in the region. Within this stratification, the Nuba were largely bereft politically and economically. At the same time, the region as a whole lagged behind other regions of the periphery, functionally tied to the centre through various forms of unequal and exploitative sociocultural, economic and political relations (Komey 2010a, 43, 2014, 19).

4. Postcolonial Marginalization, Institutionalized Insecurity, and Nuba Peaceful Struggle

When Sudan gained its independence in 1956, the bulk of the people in the peripheral regions of Sudan realized that, despite their contribution to the struggle for the new state, they were being purposely denied access to, and participation in, power and wealth sharing, coupled with socio-cultural exclusion and suppression of their identities (Roden 1974; Niblock 1987; Komey 2005). The Nuba, and their peripheral region, were no exception.

Power struggle between the economically, socially and politically dominating centre and the deprived periphery in Sudan can be traced back to the colonial history. The colonial administration concentrated development in favorable geographical regions of Sudan. After independence, regional disparity in national development was already sharp (Komey 2005). As a response, some Nuba activists established a peaceful political movement called “Nuba Mountains General Union” (NMGU) in 1957. The NMGU strove to foster development and political participation of the Nuba people while trying to promote African identity as an essential ingredient in the formation of the national character (Abbas 1973, 37).

The manifestation of this peaceful political movement was evident in the 1965 election when the NMGU managed to contest and defeat the dominant ruling elites of the Khatmiyya-based National Unionist Party and the Ansar-based Umma Party by winning eight of the thirteen seats in the region. In the same year, it submitted a petition to the central government demanding the abolition of the Poll Tax still imposed on the Nuba, despite its abolition nationwide.

However, through time, this peaceful political striving proved fruitless. The marginalization of the Nuba people in national political, socio-cultural and economic spaces continued during both the military and democratic regimes (Battahani 1986; Kadouf 2001; Komey 2010a). For example, during the first democratic national government of Ismil al-Azhari (1956–58), the ruling elite pursued strict policies of Islamization and Arabization in the education system of the whole country, with no consideration for any cultural, religious, or linguistic distinctions. To achieve complete cultural assimilation, indigenous languages were forbidden, including their banning in schools in the Nuba Mountains. Nuba children were not allowed to attend school unless they adopted Arabic names and spoke Arabic in school (Johnson 2006, 131; Saeed 1980, 19). The military regimes of Ibrahim Abud (1958–64) and Nimairi (1969–85) pursued the same policies but with greater determination towards excessive Islamization and Arabicization among Nuba children (Komey 2010a, 73).

Moreover, land grabbing was at its peak through the Mechanized Rain-Fed Farming Schemes in the region (see Bathanni 1986; Saeed 1980). As a result, the Nuba traditional farmers became strangers in their own land, with many forced to migrate to urban areas in search of new means of livelihood in central and northern Sudan. In those urban centres, however, the Nuba and other migrants faced other forms of marginalization: a brutal and forced deportation campaign, known locally as Kasha, was launched in Khartoum against all those without identification cards or employment on the pretext that they were a threat to public security and order. They were taken against their will to the area of their respective ethnic origins or otherwise to agricultural schemes in central Sudan as forced labor. According to Kadouf (2001, 51) “the Nuba, and all those with obvious African features, were the main target. The army was deployed in the streets of Khartoum to implement the decree […] the kasha was performed in a brutally humiliating and inhumane way.”

This situation, characterized by state-driven multiple forms of cultural and political exclusion and economic marginalization, paved the way for a shift from peaceful to violent political struggle in the region as detailed below.

5. Shifting from a Peaceful to a Violent Political Movement: The First War 1985–2005

After they were, rightly or wrongly, convinced that peaceful struggle is fruitless, some young Nuba leaders decided to establish several interlinked underground movements during the Nimairi military regime (1969–85), namely al-Sakhr al-Aswad (the Back Rock), Nahnu Kadugli (We are Kadugli), and Kumalo (Kadouf 2001; Komey 2010a). The emergence of these underground movements marked a turning point in the Nuba political struggle led by the late Yusuf Kuwa Mekki (1945–2001).

The 1985 event of al-intifadh—i.e., a popular uprising that overturned the Nimairi Government—created an opportunity for political freedom that encouraged the Nuba underground movements to surface. Several Nuba parties were formed including the NMGU, led by professor al-Amin Hamuda, and the Sudanese National Party (SNP), led by Fr. Philip Abbas Ghabush. The latter came to dominate regional politics in the Nuba Mountains through the election of 1986, winning eight seats in the region in the National Assembly. Despite this political representation, the Nuba and the entire region of the Nuba Mountains remain at the margins of Sudan’s economy, politics and culture.

When the civil war broke out in the South in 1983, the Nuba, particularly the active Kumalo members, were ripe for rebellion (African Rights 1995, 32; Johnson 2006, 131). The following year signified a shift to armed struggle in the Nuba Mountains when Yusuf Kuwa Mekki, among others, joined the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). Kuwa argued that:

We wanted some equality, some services; so that people could feel that they were belonging to the same country. [But] it wasn’t possible, because whenever you talked, you would be […] described as a racialist, a separatist, this and that and always they would try to find something to condemn you for. That is why we were enthusiastic to read the SPLA manifesto of 1983, which talked about fighting for the united Sudan, for equality and share of power, share of economy, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of practicing culture. That is what made us join the SPLA in 1984. We were disappointed with the situation. (Komey 2010a, 77)

Thus, the civil war that started in southern Sudan in 1983 extended gradually to northern regions via the Nuba Mountains in the mid-1980s. Since then, the Nuba Mountains, as a social space, have become a battleground between the central government and the rebel forces. The event of the Nuba joining the armed struggle under the southern-led SPLM/A signifies a shift of the conflict from its local scale to a larger civil war scale with significant repercussions on Sudan’s entire political landscape.

At the national level, two key dimensions of this event are evident. First, the event spatially extended the civil war, which was confined to the South, in the northern Sudan territory. Second, the Nuba experience was soon followed by other peripheral regions having similar land-based grievances; namely, the Igassana in southern Blue Nile, the Beja in the east, and the Darfur in the west. At the regional level, the war brought about major new territorial and political re-spacing. As the war intensified, the previously shared Nuba Mountains territory was progressively divided into two heavily militarized geo-political and administrative zones: (1) areas controlled and administered by the Government of the Sudan, with the Baqqara having the upper hand in public affairs; and (2) areas controlled and administered by the Nuba-led SLPM/A with the Baqqara nomads having no access to their traditional seasonal grazing lands and water (Komey 2010a, Komey 2010d).

The crux of the matter here is that the joining of the armed struggle by the Nuba was a political turning point not only for the history of the region but for Sudan as a whole, with far-reaching socio-political repercussions. The event extended the civil war from southern to northern parts of then undivided Sudan via the Nuba Mountains territory. One major consequence was the turning of the Nuba-Baqqara partnership into rivalry, despite the Nuba’s declaration that their original intention was to fight the government and not their local partners, the Baqqara. The Baqqara started to form pro-government militias that battled against the Nuba-led SPLA forces in the region. Thus, the tensions, and eventually the war, took on a new dimension, intensifying the antagonism between the two communities along ethno-political divides. The government took a risk and redirected the war—originally between the central government and the armed Nuba—into a conflict between two marginalized local groups. In doing so, two local and disadvantaged communities, the sedentary Nuba and the nomadic Baqqara, were made to fight each other for externally generated reasons coming from the centre of power (African Rights 1995, 23–4; Komey 2010a, 80). All the communities of the region were impacted heavily by the war, but the Nuba in the battle zone were the ones most affected as they faced Jihad, ethnocide, and genocide by attrition.

5.1: Forms of Institutionalized Insecurity: Jihad, Ethnocide, and Genocide by Attrition

At the start of the war, the government had sealed off the region, and allowed no relief into certain targeted areas of the Nuba Mountains for thirteen years to place additional food pressure upon the population. The government pursued not only military campaigns against the Nuba, but also an ideological and religious strategy aimed at destroying Nuba culture, identity, and even their very survival as an ethnic group. At the centre of this strategy was a politically driven Jihad (Mohamed Salih 1995, 1999; Africa Watch 1991; African Rights 1995; Komey 2010a).

After it sealed off the region and tightened security where no foreigners were permitted access—and Sudanese citizens had to obtain passes from the military authorities to travel in the area—the government embarked in a large military operation followed by an intensive campaign to eradicate the Nuba identity through ethnic cleansing. In great secrecy, physical genocide and cultural genocide (ethnocide) were being perpetrated. By the early 1990s, some 60 000–70 000 Nuba had been killed in government military operations—brutal campaigns virtually invisible to the outside world (Meyer 2005, 26). The army and People Defense Forces (PDFs) large-scale military operations came to have disastrous consequences with (i) a series of systematic mass killings and destruction of people’s livelihoods, with many villages reduced to ashes; and (ii) displacement with massive loss of human life. As people fled from the army and the PDFs, many died of hunger and/or thirst (Meyer 2005; African Rights 1995; Africa Watch 1991; Mohamed Salih 1995, 1999; Komey 2010a).

Several works, including African Rights (1995); Mohamed Salih (1995, 1999); Bradbury (1998); de Waal (2006, 2007); Totten (2012); and Totten and Crzyb (2014), agree that the government’s isolation of the Nuba people in the mountains amounted to a “genocide by attrition.” As one prominent scholar and human rights activist has said: “Not only did the government aim to defeat the SPLA forces but it also intended a wholesale transformation of the Nuba society in such a way that its prior identity was destroyed. The campaign was genocidal in intent and at one point, appeared to be on the brink of success” (de Waal 2006, 1). Due to the various military assaults in areas held by the government’s forces as well as in those held by the SPLM/As, the Nuba were subjected to large-scale depopulation, displacement and forced relocation processes associated with severe hunger, diseases, and mass fatality (Africa Watch 1991).

Socio-economic marginalization, political oppression, and military campaigns against the Nuba reached a climax with the emergence of the politicization and mobilization of the religious factor in the civil war (Mohamed Salih 2002; African Rights 1995; Kadouf 2001, 2002; Manger 2001–2002; Komey 2010a). As the war intensified in the region, the government changed its war tactics by evoking the religious factor. It declared a Holy War, the Jihad, against the Nuba. On 27 April 1992, a fatwa (an Islamic decree) was issued, in a conference in El Obeid, the capital of North Kordofan, on the pretext of fighting the SPLM/A forces (which included a substantial number of Nuba Muslims). For that purpose, the fatwa extended the definition of apostasy by declaring that:

The rebels in southern Kordofan and southern Sudan started their rebellion against the state and declared war against Moslems. Their main aims are killing women, desecrating mosques, burning and defiling the Quran, and raping the Moslem women. These foes are the Zionists, the Christians and the arrogant people who provide them with provisions and arms. Therefore, an insurgent who was previously a Moslem is now an apostate; and a non-Moslem is now a non-believer standing as a bulwark against the spread of Islam, and Islam has granted the freedom of killing both of them. (Manger 2001, 49–50, 2001–2002, 132–33; African Rights 1995, 289; Johnson 2006, 133; Komey 2010a, 84)

This widely quoted fatwa and the subsequent supporting Jihad arrangements came to have far-reaching and multifaceted implications for the war waged against all Nuba, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, and their respective religious institutions including mosques in the SPLA-held area. The government imposed a “territorial distinction distinguishing the Dar al–Islam (Abode of peace) from the Dar al–Harb (Abode of war). Mosques found outside government control have been destroyed and defaced, and Muslims enjoined to relocate themselves to the Dar al–Islam of government garrison” (Johnson 2006, 133).

However, from the viewpoint of the majority of the Nuba, the war being waged was not a religious one. It was, rather, a war against their African identity and for possession of their ancestral land (see Komey 2008, Komey 2010a, Komey 2010b, Komey 2010d). For them, the declared Jihad was merely an act of politicizing religions along ethnic lines by the Arab-Islamic ruling elite in order to continue consolidating their economic, political, and socio-cultural domination over the Nuba (Kadouf 2001, 57–61; Komey 2010a, 84).

5.2: Playing Identity Politics for Physical Survival

and Cultural Resilience

During the long war, the Nuba communities, in the SPLM/A held areas in the Nuba Mountains, exercised different forms of survival strategies, mechanisms, resilience and resistance. Along with others, I have discussed in several contributions how the Nuba elites played the identity politics card to avert the government-led ethnocide and genocides during the 1987–2005 war (see Komey 2009a, 2009b, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Manger 2001, 2001–2002; Mohamed Salih 1995, 1999). The focus here is on the 1983–2005 war period. Describing the exceptional performance of the Nuba resistance, de de Waal (2006, 7) asserts that there was “no humanitarian presence in the region at all. There was no news coverage, and in any case the people in the mountains had no batteries for their radios. The Nuba felt forgotten by everyone. With nothing but themselves to rely on, they found [the] necessary determination and reserves of energy.” Winter (2000, 60) referred to the Nuba experience of resistance, resilience, and self-reliance during the long period of isolation as something unique and unprecedented. He stated that:

[in] today’s pattern of conflict, in which communal and ethnic struggles predominate and civilians rather than opposition militaries are the primary target, much of what is seen in the Nuba Mountains is not unique. What is rare, however, is that such a war by a government against a civilian population is being waged so invisibly. The years-long isolation of the victims is unique in the case of the Nuba. As a result, the Nuba have been forced into a pattern of self-reliance that is also not common. (Ibid.)

Through this self-reliance and resilience, the Nuba eventually overcame the genocide. The Nuba fought with virtually no outside assistance, demonstrating a remarkable toughness and ability to defy all odds. But the future of the people of the Nuba Mountains still hangs by a thread (Komey 2010a, 88). One of Nuba’s unique forms of resilience during the war was the ability of its leaders to establish an exceptional civil administration in war zones. In the midst of the catastrophic military operations and the outcries of the suffering people, Commander Yusuf Kuwa initiated the formation of a civilian institution, an Advisory Council, in the Nuba SPLA-controlled areas. This significantly boosted popular support for continuing the armed struggle.

On 30 September 1992, a five-day conference of the Advisory Council convened in Debi with one topic on the agenda: Whether or not to continue the armed struggle. After two days of orientation, Commander Kuwa concluded that “Up to today, 1 October 1992, I am responsible, I take responsibility for everything that has happened in the Nuba Mountains up to now. But, from today, I will not be responsible. If we are to continue the war, then this must be our collective decision.” On the final day, the Advisory Council voted overwhelmingly to continue the armed fight despite their total isolation from the outside world and the grave increase in the incidence of genocidal and ethnocidal atrocities in the government’s military offensives (African Rights 1995, 131; Komey 2010a, 86).

The event was described in dramatic terms by many writers, such as Meyer (2005) and de Waal (2006), as a rare situation in which a political leadership has to rely entirely on the wishes and support of its constituency for its own survival. As a civil administration parallel to the military administration in the region, the Advisory Council put “the Nuba on a unique experiment in popular wartime democracy” (Meyer 2005, 91). This was unprecedented throughout the SPLM/A-controlled areas. In the words of de Waal (2006, 6), “their resilience bought time: by slowing down the advance of the government troops, they ultimately defeated the genocide.”

With these collective and newfound reserves of determination, the Nuba fought on in the following years with resourcefulness and self-belief, while the civil administration opened schools and clinics. All this was accomplished with no financial support or external assistance. That is why, “when international agencies began to operate in the Nuba Mountains in 1995, they were first impressed with the self-reliance and pride of the people” (de Waal 2006, 7; Meyer 2005).

Another important achievement of this civil administration was that it established several secretariats specialized in the fields of health, education, agriculture and animal resources, among others. In close collaboration with some international agencies, the secretariats have played a vital role in delivering basic needs and services to the Nuba people, not only during the war period but also during the transitional period during which the government services in the former SPLM/A-controlled areas were negligible (Komey 2010a, 86).

Solidarity through global advocacy campaigns was another form of resilience and resistance exercised by the Nuba community during the war. At a time of total isolation, with no news available from the Nuba Mountains, the Nuba diaspora made a tremendous effort to reveal to the international community the atrocities being perpetrated by the army, security and PDF forces. Thus, they played a key role in reinforcing international support to redress this human tragedy through a series of solidarity campaigns, in collaboration with international organizations and human rights activists. As a result, the aims of the atrocities of the secret war, to eradicate Nuba identity or even their very existence, were widely disseminated. Reports revealed that the Nuba resisted this programme of genocide while in complete isolation due to their fearless resistance, self-reliance and unprecedented resilience (Meyer 2005; Komey 2010a, 87).

During the civil war, some Nuba elites in diaspora were especially able to promote the Nuba cause internationally as endangered indigenous communities. Towards that end, several Nuba entities were formed in the 1990s in Europe and elsewhere. These included “Nuba Solidarity Abroad”; “Nuba Survival Organization” and its newsletters Nafir and The Nuba Vision in London; and “Nuba Relief, Rehabilitation and Development Organization” (NRRDO) founded in 1996 in Nairobi, Kenya.

The world was progressively informed of the government’s genocidal intent towards the Nuba through a series of reports and publications. These included Sudan: Destroying ethnic identity: the secret war against the Nuba (Africa Watch 1991); Sudan: Eradicating the Nuba (Africa Watch 1992); Facing genocide: the Nuba of Sudan (African Rights 1995); Resistance and response: ethnocide and genocide in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan (Mohamed Salih 1995); Land alienation and genocide in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan (Mohamed Salih 1999); The right to be Nuba: the story of a Sudanese people’s struggle for survival (Rahhal 2001); Modernization and resistance: the plight of the Nuba People (Kadouf 2001); War and Faith in Sudan (Meyer 2005); Averting genocide in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan (de Waal 2006); Proud to be Nuba: faces and voices (Ende 2007).

These massive human violations, lasted throughout the 1990s and only ended in late January 2001, when the government allowed the delivery of international aid to the Nuba Mountains for the first time since 1986. This came as a result of Senator John Danforth’s peace initiative, which culminated in the signing of the Cease Fire Agreement in January 2002.

6. Renewed War and Civilians’ Responses in the “Killing Fields”

The renewed conflict in South Kordofan and the Blue Nile in 2011 is largely a continuation of the Second Civil War (1983–2005) fought by the SPLM/A against the Sudanese government’s centralization of power and wealth and increasing homogenization of the country’s society. These issues were left largely unresolved by the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) (Alessi 2015, 12). It is worth noting that the basic premise of the CPA signed in 2005 was to provide a comprehensive and lasting solution to the root causes that led to the civil war in Sudan. But the CPA allowed only for a transitional period of relative peace before the war resumed in the two regions. It resumed first in South Kordofan in June 2011, and expanded to the Blue Nile in September 2011. The heart of the matter is that instead of providing durable peace, the CPA prepared the political ground for another violent phase in the two areas (see Small Arms Survey 2008; ICG 2008, 2013; Komey 2013b; Rottenburg, Komey, and Ille 2011).

Since then, the second war in the two regions has continued unabated with far-reaching repercussions on the civilians and their livelihoods (see Komey 2011, 2013a; Ille, Komey, and Rottenburg 2015). As shown in more detail in the subsequent analysis, the resumption of war in 2011 in the Blue Nile and Nuba Mountains shows that “the CPA was not a ‘comprehensive’ and ‘final’ settlement to Sudan’s recurring political conflicts. It was rather a long-term truce or ceasefire, at least as far as northern Sudan was concerned” (Ille, Komey, and Rottenburg 2015, 118). Thus, the ongoing conflict has been perceived elsewhere (Komey 2014) and here as well, not as a singular event on a time axis but as a continuation of Sudan’s violent episodes that characterizes its precolonial, colonial and postcolonial eras.

6.1: Triggering Factors, Intensity, and Massive Human Atrocities of the Renewed War

Several successive contributions affirm that the renewed war in these two regions was triggered and subsequently sustained by several factors; namely, the CPA’s failure to redress the political question in the two regions (Komey 2010a, 2013b; Gramizzi and Tubiana 2013). After the end of the transitional period, it was clear that key provisions of the CPA remained without implementation. Other triggering factors included tensions over the fate of the Nuba-led SPLA and heated disputes over elections in the region (Verjee 2011; Ille, Komey, and Rottenburg 2015). Other factors contributed even more to rising tensions, like the unresolved status of Nuba SPLA combatants (Gramizzi and Tubiana 2013) and popular consultations as a mechanism for resolving conflicts in the two regions (Komey 2013b).

Unlike the previous war (1987–2005), the second war in the two regions, which continues to this day, proved to be more brutal, intensive and extensive. Within just a few weeks, this “new war” saw the mobilization of thousands of men and huge quantities of weapons and ammunition, air strikes, and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. The new conflict pits Sudanese forces—the national army and paramilitaries—against the northern branch of the SPLM, including former members of the southern SPLA, and allied elements of the Darfur armed opposition (Gramizzi and Tubiana 2013, 8).

Since the beginning of the war in 2001, numerous reports document a wide scale of gross human rights violations, including mass arrests of Nuba civilians, forced displacement of hundreds of people, arbitrary executions, and cases of rape and sexual violence perpetrated by Khartoum-backed militias as well as ordinary security forces. At the beginning of the conflict in particular, civilians and civilian areas considered to be pro-rebel—reportedly on the basis of ethnicity or election results—were allegedly targeted in a systematic manner (see UNMIS 2011; Rottenburg, Komey, and Ille 2011, 10; Gramizzi and Tubiana 2013, 23). Some reports contain evidence that SAF used a number of indiscriminate weapons during its military operations. The Small Arms Survey identified anti-personnel and anti-tank landmines, as well as unexploded sub-munitions from a cluster bomb (Gramizzi and Tubiana 2013, 43).

SAF reportedly used more sophisticated and harmful weapons, including cluster bombs, longer range rockets, and drones. It quickly intensified the use of these more advanced military capabilities for both air and ground bombardments indiscriminately. Recently, Amnesty International reported:

That has predominantly involved the use of unguided bombs rolled or pushed out of the back of high-flying Antonov aircrafts, a type of attack which does not allow for accurate targeting to distinguish between civilians and civilian objects on the one hand, and legitimate military targets on the other in civilian populated areas. (Amnesty International 2015, 6, 13)

To demonstrate the intensity of this second war and its brutality on civilians, Amnesty International (2015, 13) reported that between January and April 2015, an estimated 374 bombs were dropped in 60 locations across South Kordofan. The result was the death of an estimated 35 civilians, with approximately 70 injured. In addition to the numerous accounts of bombings, there were repeated long-range ground shelling attacks on villages and IDP sites, and against or very close to hospitals, medical clinics, schools, homes and market areas, which killed or injured civilians and destroyed civilian targets. Another report revealed that the “relentless bombing is accompanied by a scorched earth campaign on the ground designed to destroy crops, disintegrate communities, and starve the rebel forces into submission. Thousands of civilians have taken to living in caves: the only refuge from the bombs and the indiscriminate violence” (IRIN NEWS 2015, 1).

One member of the community describes the uncertainty surrounding people all the time and in all places: “Bombs have fallen in hospitals, schools and foxholes. Little babies and the very old have been killed. In South Kordofan I don’t think that there is anywhere that is safe, and I don’t think there is anyone who is safe” (Amnesty International 2015, 13). From 2011 to the end of 2015, it was reported that “more than 3 000 bombs have been dropped on civilian targets in rebel-held territory of South Kordofan” (All Africa 2015).

The intensity of the war manifests itself in the government’s sustained dry season offensives, which started in 2012. On 12 November 2013, the Government of Sudan (GoS) announced that its third dry season offensive would begin in 2014. Despite the massive fighting and displacement of the population, the third dry season ended with the overall military status quo largely unchanged. The government then changed its strategy when it announced its first “decisive summer campaign” against the rebels in the region (Alessi 2015, 16). The dry seasons of 2014 and 2015 saw the largest offensives since the fight started in 2011, where the newly trained Rapid Support Force (RSF) was moved into the region as a critical new element in the fight against SPLA-N.

A massive government offensive against the rebel SPLA-N in South Kordofan managed to end many lives, but did little to change the frontlines of the conflict: SPLA-N continues to hold much of the territory across the Nuba Mountains, while SAF controls the state’s major towns. It was the largest offensive since the new stage of Sudan’s civil war started in 2011. The initial attack in 2014 was successful in putting the government forces within striking distance of the rebel’s political capital, Kauda. But the offensive could not be sustained. Within a couple of weeks, SPLA-N regained its original positions (Nuba Reports 2015b, 1). Each campaign tends to cause a wide-scale humanitarian crisis in terms of sizable civilian causalities associated with massive influx of both IDPs and refugees.

Through this series of “decisive summer campaigns,” the government meant to create persistent institutional insecurity among the civilians in clear violation of the fundamental rule of international humanitarian law that parties to any conflict must at all times distinguish between civilians and combatants. The affected communities adopted different types of survival mechanisms in order to cope with key threats to minimize the damage caused to their lives and properties.

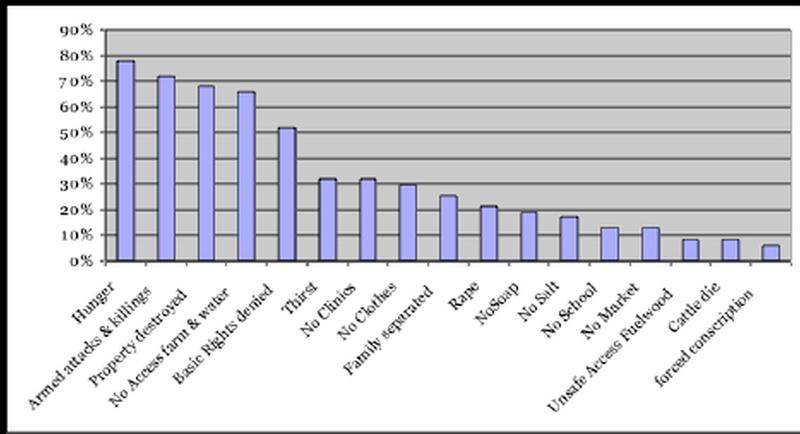

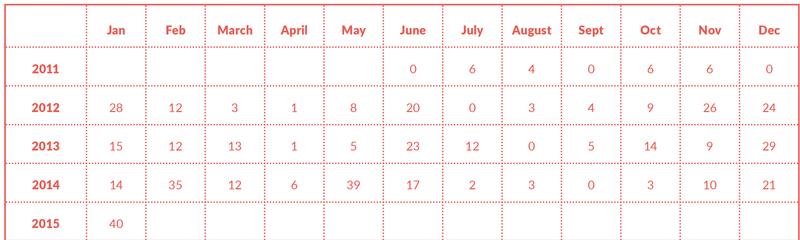

Table 1 below demonstrates the frequency of responses related to core survival threats faced by civilians on the battleground. The table indicates that the problems most commonly facing civilians in war zones fall into two categories. The first category of threats is related to hunger due to restricted or unsafe access to farm land, forced displacement, loss of livestock, and agricultural inputs, death of family labour, lack of access to markets, loss of employment, lack of disposable income. The second category is related to human security risks that may result, at any point in time and space, in injury and or death due to military attack through ground forces and militias, artillery and aerial bombing, mines, poisoned wells, abduction, and rape (to mention a few). The results are massive human rights violations and humanitarian crises among civilians in war zones.

Table 1: Frequency of Responses Related to Core Survival Threats. Source: Corbett 2011, 14.

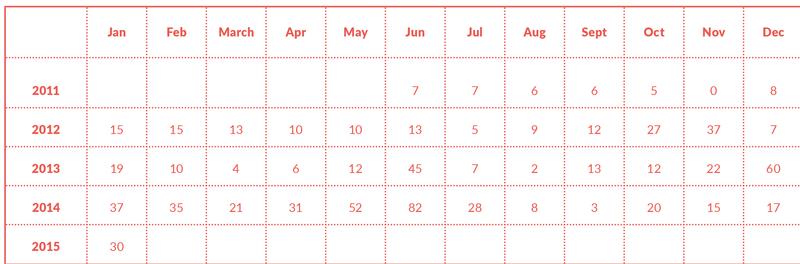

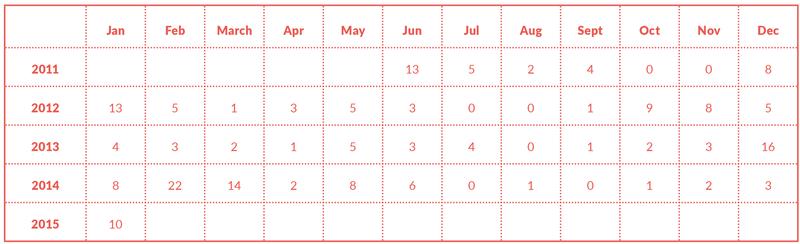

Table 2, below, summarizes the number of confirmed bombing and shelling attacks on civilian objects in South Kordofan during the June 2011–January 2015 time period; while Tables 3 and 4 provide the number of confirmed dead or injured civilians as a result of bombing and shelling attacks from June 2011 to January 2015. A quick glance at the figures shown in the three tables demonstrates that war intensified after “decisive dry season campaigns” that started in 2014, resulting in a sharp increase in number of deaths and injuries during the dry season, particularly during the January-March period of 2014.

Table 2: Number of confirmed bombing and shelling attacks on civilians and civilian objects in southern Kordofan, June 2011–January 2015. Source: The Sudan Consortium: African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan 2015, 3.

Table 3: Confirmed number of civilian deaths by bombing and shelling attacks in southern Kordofan, June 2011–January 2015. Source: The Sudan Consortium: African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan 2015, 4.

Table 4: Confirmed number of civilians injured by bombing and shelling attacks in southern Kordofan, June 2011–January 2015. Source: The Sudan Consortium: African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan 2015, 5.

Although it is difficult to verify the accuracy, therefore, the reliability of the provided statistics, they reflect, to some degree, the reality of civilian suffering in the killing fields. This is due to the fact that, unlike the previous war of 1987–2005 in the Nuba Mountains, this war is fought by a sizable generation of educated and trained young individuals from the area. Their know-how and technical skills seem to be making a significant difference. For example, the Nuba Reports are “produced by a network of journalists from the Nuba Mountains. They know the conflict better than anyone. Armed with cameras and journalistic training, they have returned to their homeland to document the conflict for audiences both inside and outside Sudan” (Nuba Reports 2016, 1).

Despite the intensity of the war associated with indiscriminate use of more advanced military devices and arms, civilian survivors remain resilient. Each individual and family deploys a set of survival mechanisms in order to reduce risk and insecurity. The following subsection outlines some of those mechanisms.

6.2: Some Civilians’ Survival Responses and Mechanisms

During the first war, the affected communities developed several survival tactics. Some of those tactics were implemented when the war resumed, while new ones were developed in response to new weapons used in the second war. As detailed below, the survival mechanisms and responses can generally be categorized into physical survival and economic resilience.

(i) Physical Survival

Civilians responding to physical threats, and who remain within their homeland after evacuating their homes, usually adopt a combination of the following strategies:

- In the face of displacement, people seek physical safety from military attacks by leaving their homes to live in the mountains, or move out of the war zone altogether to live elsewhere in northern Sudan.

- In a situation mounted with insecurity and risk, individuals may use trees and plants for basic needs like food, medicine, soap, and clothes.

- People invest in social networks and communal solidarity.

- Some individuals only undertake activities at night to reduce risk of exposure to violence

(Corbett 2011, 22; bold in original).

Using the mountains of their homeland as a resource is one of the most important survival mechanisms deployed by civilians in war zones. Several informants testified that: “We survived because of three things: the mountains, the forests and the unity of the people.” Another individual pointed out that: “Our safety was from the mountains, our food and medicine from the trees and wild plants, our support was from one person and to another. The mountains protected us. We ate wild food and treated ourselves with traditional medicines. We depended on our communities, collaboration and unity to help each other to survive and not give up” (Corbett 2011, 22). The protective element of the mountains is not something new for the Nuba, as they relied on it for survival during different types of violent campaigns carried out throughout their precolonial, colonial and postcolonial histories. In fact:

For generations the Nuba people have sought physical safety from armed attack by fleeing their homes in the plains to live up in the mountains. Indeed, the Nuba tribes are thought to have settled this uniquely mountainous part of northern Sudan many centuries ago for precisely this reason. With their knowledge of the area and its hidden paths, caves, sources of water, forests and cultivatable areas, they have proved time and again the efficacy of such a strategy. (Corbett 2011, 23)

Apart from using the mountainous features of their homeland as resources by hiding in caves during conflicts or bombings, Nuba civilians also resort to borders as a survival strategy, through long-range spatial mobility. The most significant difference between the first and the second war in the Nuba Mountains is the change in direction of the geographical (spatial) movement of the affected population. During the first war, most of the affected communities moved northwards seeking refuge as IDPs in the Sudan government-controlled areas, while some remained in their homeland in SPLA-controlled areas. There were almost no waves moving southwards to southern Sudan (Komey 2013a, 99). As IDPs, they experienced gross human violations, described by many as “genocide in intent” or “genocide by attrition” (Mohamed Salih 1995 Totten 2012; Totten and Cryzeb 2014).

In the current war, however, a sizable number of the affected Nuba moved southwards and crossed the border to seek refuge inside the South Sudanese territory for their physical survival (Komey 2013a). “Resourcing borders,” for physical security and protection, as well as for economic interest is indeed an interesting concept. Mobility of people, ideas, goods and services across internationalized borders is currently a conspicuous feature as individuals seek refuge and security beyond their territories due to the intensity of war, and particularly because of air bombardments by the government of Sudan. The Yida refugee camp, 12 miles inside South Sudan and with a population of more than 80 000 (Voice of America 2015), is illustrative of war-affected people seeking refuge and security through spatial mobility beyond borders (UNHCR. 2015).

Three key factors played a decisive role in this reversed pattern of movement as a survival strategy. First, the legacy of the shared armed struggle with the people of South Sudan during the first war promoted a sense of social belonging and political attachment to South Sudan rather than to Sudan. Second, for the Nuba IDPs, the independence of South Sudan provided a feeling of security beyond the reach of the Government of Sudan (Komey 2013a). Third, the legacy of the previous war and its painful memories suggests that it is better for the affected people to seek refugee status or even an alternative citizenship in South Sudan than to expose themselves to the risk of another massive violation of human rights similar to that experienced by the IDPs in the government-controlled areas during the first war (1987–2005) in the region (Komey 2013a, 99). In a nutshell, the war-affected communities continue resourcing borders for their own physical survival despite its internationalization after the separation of South Sudan. But “the relocation strategies of threatened families to protect safety and livelihoods resulted in severe psychological suffering associated with alienation and lack of belongingness” (Corbett 2011, 27).

(ii) Economic Resilience

As in the previous conflict, as the war intensified, the bulk of the Nuba communities in the areas under the control of the SPLM/A-N were completely cut off from supplies of all basic urban commodities and services that used to flow from the major towns in the northern and central parts of Sudan. Hence, their livelihoods and daily life were not only radically transformed, but their very survival was also endangered. It is within this context that a phenomenon of sporadic market exchange, known locally as suk sumbuk, re-emerged along the divides between the government- and rebel-controlled areas (see Komey 2010a). During this war, it was reported that:

An enormously important initiative for livelihood protection by the besieged Nuba were the clandestine negotiations with Arab traders from GOS-controlled areas that led to the establishment of covert (and transient) cross-line markets and opportunities for trade. The existence of these markets depended on local agreements between groups across conflict lines—often highly complex and always very sensitive and fragile. The markets were risky from a security point of view and were very expensive for the besieged Nuba, but (until INGO interventions started towards the end of the war) they provided the only supply of basic commodities. These included life-saving items such as salt, soap, matches, some medicines (paracetamol, broad-spectrum antibiotics, anti-malarials) as well as more “luxurious” basics such as sugar, tea, needles and razors, mirrors, cooking utensils, batteries (for transistor radios and torches), clothes, wheat flour, yeast, some vegetable seeds, bicycles, tools, and weapons. Since there was little or no cash for many of the war years in the opposition areas, barter with livestock was the main currency of trade. (Corbett 2011, 39)

Resourcing borders is not only for the purpose of physical survival but also for economic survival. The Nuba refugees perceive proximity to border as a resource/safe haven because security is seen as more bound up with cross-border kinship connections than with the provision of security by government or international organizations (UNHCR. 2015). Thus, cross-border local trade and economic transactions intensified along the border areas under SPLM-N control despite the formal closure of the border. This is to the degree that some areas along the south-north border have become zones of overlapping economic sovereignty and active intermediary economic spaces for these war-affected communities. Different types of currencies, in fact, are used interchangeably; namely, old and new Sudan banknotes, South Sudanese banknotes, and $US. In some cases, and where there is severe shortage of cash, exchange of commodities in kind (barter trade) is practiced.

Another economic survival mechanism is the utilization of social media technologies and mobile phones for economic transactions, including money transfers, as well as for exchange of information of economic utility between the divided members of families. Technology is not only being deployed to communicate but also for financial transferring purposes within families that no longer live together. For example, when war broke out in 2011, several families were disconnected along the divides of the government and SPLM/A-N areas. There are often family members in government-controlled areas who need to send money to their relatives in the war zone, or vice versa. Such a transaction would have been normal practice during peace times. But the war put an end to that as areas controlled by the SPLM/A-N were formally cut off from the rest of the country.

7. Conclusion

Photo by Tim Freccia / Enough Project. CC-license.

Precolonial, colonial and postcolonial histories indicate that the current human tragedy facing the Nuba people is not something new. Rather, it is a continuation of episodes of institutionalized insecurity and perpetual violence driven by more powerful forces, including the state. The current war represents a violent phase of a situation that has always characterized the region’s history with territory and identity standing as two key drivers for their constant struggle (Manger 2007, 72). The crux of the matter here is that the fundamental problem in the Nuba Mountains/South Kordofan is political. As such, it will be resolved only by a political agreement that acknowledges the rights of the currently socio-politically excluded and economically marginalized.

The overall analysis reveals that the ongoing violent conflict in the Nuba Mountains in southern Kordofan is one of the biggest human tragedies not only in postcolonial Sudan but also in contemporary Africa and the world at large, worsened by the lack of humanitarian help allowed in the area. Because of how pervasive the conflict is and based on the scarcity of outside intervention, civilians resorted to different types of self-protection and survival mechanisms and strategies. However, despite these survival mechanisms, deaths, injuries, and displacements are still very high.

Moreover, the analysis concurs with other contributions that point to the importance of the fundamental role of threatened communities in protecting themselves from violence. It also highlights that, however remarkable such self-protection, there will be death and suffering on a terrible scale if state-sponsored violence against civilians is not prevented by other actors.

The self-protection strategy is necessary but not sufficient as it still results in high levels of mortality and suffering. The plight of the Nuba and other war-affected communities in the Blue Nile and Darfur, associated with state-driven institutionalized insecurity and excessive violence against the civilians, poses a serious question as to whether there is a tradeoff between state sovereignty and maintaining basic human rights and needs. Keeping civilians in such tragic circumstances is a real test for the fundamental principles of the “responsibility to protect” that goes with humanitarianism and humanitarian international laws and practices. The case at hand would suggest that state and international systems and regulations failed at that.

Nuba demonstrating cultural resilience in the capital Khartoum during their celebration of the International Day for the Indigenous Peoples in Dar EL-Nuba in Omdurman. Photo taken by the Author, August 2015, Khartoum.

References

Abbas, Philip Ghabush. 1973. “Growth of Black Political Consciousness in Northern Sudan.” Africa Today 20, no. 3: 29–43.

African Rights. 1995. Facing Genocide: The Nuba of Sudan. London: African Rights.

Africa Watch. 1991. Sudan. Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Secret War against the Nuba. London: Africa.

———. 1992. Sudan: Eradicating the Nuba. London: Africa Watch

All Africa. 2015. Sudan: Bombings Exceed 3 000 in the Nuba Mountains. http://allafrica.com/stories/201502161088.html.

Ahmed, Ghaffar M. and Gunnar M. Sørbø (eds.). 2013. Sudan Divided: Continuing Conflict in a Contested State. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Alessi, Benedetta de. 2015. Two Fronts One War: Evolution of the Two Areas Conflict, 2014–2015. Geneva: Small Army Survey, Graduate School of International Development Studies.

Amnesty International. 2015. Don’t We Matter: Four Years of Unrelenting Attacks against Civilians in Sudan’s South Kordofan State. London: Amnesty International.

Battahani, Atta El Hassan El. 1980. The State and the Agrarian Question: A case study of South Kordofan 1971–1977. Khartoum: University of Khartoum.

———. 1986. “Nationalism and peasant politics in the Nuba Mountains region of Sudan, 1924–1966.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sussex.

Bellal, Annyssa. 2014. The War Report: Armed Conflict in 2014. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beny, Laura Nyantung and Sondra Hale (eds.). 2015. Sudan’s killing fields: political violence and fragmentation. Trenton, NJ: The Red Sea Press, Inc.

Bradbury, Mark. 1998. “Sudan: International responses to war in the Nuba Mountains.” Review of African Political Economy 25, 77: 463–74.

Corbett, Justin. 2011. Learning from the Nuba: Civilian resilience and self-protection during conflict. London: Local to Global Protection.

Deng, Francis Mading. 1995. War of Visions. Conflict of Identities in the Sudan. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Ende, N. Op’t. 2007. Proud to be Nuba: Faces and Voices. Amsterdam: code x.

Gillan, J. A. 1930. Arab-Nuba Policy (Arab overlordship). Durham: University of Durham, Sudan Archive: 723/8/10–12.

———. 1931. Some Aspects of Nuba Administration: Sudan Government Memoranda No. 1. Khartoum: Government of Sudan.

Gramizzi, C., and Jerome Tubiana. 2013. New war, old enemies: Conflict dynamics in South Kordofan. Geneva: Small Arms Survey and Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

Human Security Centre. 2005. Human security report 2005: war and peace in the 21st century. Oxford University Press, USA.

Ille, Enrico. 2015. “The Nuba Mountains during the Mahdist Rule.” Northeast African Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2015: 1–64.

Ille, Enrico, Guma K. Komey, and Richard Rottenburg. 2015. “Tragic entanglements: vicious cycles and acts of violence in south Kordofan.” In Sudan’s killing fields: political violence and fragmentation, edited by Nyantung Beny and Sondra Hale. Trenton, NJ: The Red Sea Press, Inc.

International Crisis Group (ICG). 2008. Sudan’s Southern Kordofan Problem: The Next Darfur Africa Report No. 145. Brussels.

———. 2013. Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (1): War in South Kordofan, Africa Report No. 198. Brussels.

Irin News. 2015. Forgotten Conflicts – South Kordofan: the Nuba, Prisoners of Geography. http://newirin.irinnews.org/forgotten-conflicts-sudan-south-kordofan-nuba-feature/.

James, Wendy. 2007. War and Survival in Sudan’s Frontierlands: Voices from the Blue Nile. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Douglas. H. 2006. The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars: Updated to Peace Agreement. Oxford: James Currey.

Lloyd, W. 1908. “Appendix D: Report on Kordofan Province, Sudan.” In Sudan Archives: SAD783/9/40–86. Durham: University of Durham.

Kadouf, Hunud Abia. 2001. “Marginalization and Resistance: the Plight of the Nuba People.” New Political Science 23, 1: 45–63.

———. 2002. “Religion and Conflict in the Nuba Mountains.” In Religion and Conflict in Sudan, edited by Yusuf Fadl Hasan and Richard Gray, 107–113. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa.

Komey, Guma Kunda. 2005. “Regional Disparity in National Development of the Sudan and Its Impact on Nation-Building: With Reference to the Peripheral Region of the Nuba Mountains.” PhD Dissertation, University of Khartoum.

———. 2009a. “Striving in the Exclusionary State: Territory, Identity and Ethno-politics of the Nuba, Sudan.” Journal of International Politics and Development 7(2): 1–20.

———. 2009b. “Autochthonous identity: its territorial attachment and political expression in claiming communal land in the Nuba Mountains region, Sudan.” In Raum – Landschaft – Territorium. Zur Konstruktion physischer Räume als nomadische und sesshafte Lebensräume (Nomaden und Sesshafte 11), edited by Roxana Kath and Anna-Katharina Rieger. Wiesbaden, Reichert: 205–28.

———. 2010a. Land, Governance, Conflict and the Nuba of Sudan. London: James Currey.

———. 2010b. “Land Factor in War and Conflicts in Africa: the Case of the Nuba Struggle in Sudan.” In Wars and Peace in Africa: History, Nationalism and the State, edited by Toyin Falola and Raphael C. Njoku, 351–81. Durham NC, Carolina Academic Press.

———. 2010c. “The Comprehensive Peace Agreement and the questions of identity, territory and political destiny of the indigenous Nuba of the Sudan.” International Journal of African Renaissance 5(1): 48–64.

———. 2011. “The Historical and Contemporary Basis of the Renewed War in the Nuba Mountains.” Discourse 1, 1(2011): 24–48.

———. 2013a. “The Nuba Political Predicament in Sudan(s): Seeking Resources Beyond Borders.” In The Borderlands of South Sudan: Authority and Identity in Contemporary and Historical Perspectives, edited by Christopher Vaughan, Mareike Schomerus and Lotje de Vries, 89–109. Bringstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

———. 2013b. “Back to War in Sudan: Flawed Peace Agreement, Failed Political Will.” In Sudan Divided: Continuing Conflict in a Contested State. Basingstoke, edited by Ghaffar M. Ahmed and Gunnar M. Sørbø, 203–22. Palgrave Macmillan.

———. 2014. “The Nuba Plight: An Account of People Facing Perpetual Violence and Institutionalized Insecurity.” In Conflict in the Nuba Mountains From Genocide-by-Attrition to the Contemporary Crisis in Sudan, edited by Samuel Totten and Amanda Grzyb, 11–35. London: Routledge.

–––.2010d, ‘Ethnic Identity Politics and Boundary Making in Claiming Communal Land in the Nuba Mountains after the CPA’, in Elke Grawert (ed.): After the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in Sudan: Sign of Change? London, James Currey: 110–129.

–––. 2008. “the denied land rights of the indigenous peoples and their endangered livelihood and survival: the case of the Nuba of the Sudan”. Ethnic and Racial Studies 31(5): 991–1008.

MacMichael, Harold A. 1912/67. The Tribes of Northern and Central Kordofan. London: Frank Cass, 2nd edn.

———. 1922/67. A History of the Arabs in the Sudan and some account of the people who preceded them and of the tribes inhabiting Dar Fur. Vol. 1, London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

Manger, Leif. 2001. “The Nuba Mountains: battlegrounds of identities, cultural traditions and territories.” In Sudanese Society in the Context of War: Papers from a seminar at the University of Copenhagen, edited by Maj-Britt Johannsen and Niels Kastfelt. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

———. 2001–2002. “Religion, Identities, and Politics: Defining Muslim discourses in the Nuba Mountains of the Sudan.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 4: 111–31.

———. 2007. “Ethnicity and post-conflict reconstruction in the Nuba Mountains of the Sudan: Processes of group-making, meaning production and metaphorization.” Ethnoculture 1: 72–84.

Meyer, Gabriel. 2005. War and Faith in Sudan. New York: William B. Eerdman Publishing Company.

Mohamed, M. A. and M. Fisher. 2002. “The Nuba of Sudan”. In Endangered Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, edited by R. K. Hitchcock and A. J. Obsorn Westport, 115–128. London: Greenwood Press.

Mohamed Sali, M. A. 1995. “Resistance and Response: Ethnocide and Genocide in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan.” Geo–journal 36, no. 15: 71–78.

———. 1999. “Land Alienation and Genocide in the Nuba Mountains.” Cultural Survival Quarterly 22, no. 4: 36–38.

Niblock, Tim. 1987. Class and Power in Sudan: the Dynamics of Sudanese Politics 1898–1985. London: Macmillan Press.

Nuba Reports. 2015a. Thousands Flee Refugee Camp As Opposition Seize Unity State. http://nubareports.org/thousands-flee-refugee-camp-as-opposition-seizes-unity-state/.

———. 2015b. Summer Offensive Sweep Across Sudan. http://nubareports.org/summer-offensive-sweeps-across-sudan/.

———. 2016. About Nuba Reports: News and Films from Sudan’s Frontline. http://nubareports.org/about-nuba-reports.

Pallme, Ignatius. 1844. Travels in Kordofan. London: J. Madden and Co. Ltd.

Rahhal, Suleiman Musa. 2001. The Right to be Nuba: The Story of a Sudanese People’s Struggle for Survival. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press.

Roden, David. 1974. “Regional inequality and rebellion in the Sudan.” Geographical Review 64, 4: 498–516.

———. 1975. “Down-migration in the Moro Hills of Southern Kordofan.” Sudan Notes and Records 53: 79–99.

Rottenburg, Richard, Guma Kunda Komey, and Enrico Ille. 2011. The Genesis of Recurring Wars in Sudan: Rethinking the Violent Conflicts in the Nuba Mountains/South Kordofan. Halle: University of Halle.

Saeed, Mohamed H. 1980. “Economic Effects of Agricultural Mechanization in Rural Sudan: the Case of Habila, Southern Kordofan.” In Problems of Savannah Development: the Sudan Case, edited by Gunner Haaland, 167–84. Norway, Bergen: University of Bergen, Department of Social Anthropology.

Savaadra, M. 1998. “Ethnicity, Resources and the Central State: Politics in the Nuba Mountains, 1950 to the 1990s.” In Kordofan Invaded: Peripheral Incorporation and Social Transformation in Islamic Africa, edited by Endre Stainsen and Michael Kevene, 223–253. Lieden: Brill.

Sagar, J. W. 1922. “Notes on the History, Religion and Customs of the Nuba.” Sudan Notes and Records 5: 137–56.

Salih, Kamal al Din Osman. 1982. “The British Administration in the Nuba Mountains Region of Sudan 1900–1956.” Ph.D. thesis, University of London.

Small Arms Survey. 2008. “The Drift Back to War: Insecurity and Militarization in the Nuba Mountains.” Sudan Issue Briefs 12.

Spaulding, Jay. 1982. “Slavery, Land Tenure and Social Class in the Northern Turkish Sudan.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 15, 1: 1–20.

———. 1987. “A Premise for Precolonial Nuba History.” History in Africa 14: 369–374.

Sudan Consortium. 2016. African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan Human Rights Update June 2015 Eight cluster bombs fall on Umdorein County: http://www.sudanconsortium.org/darfur_consortium_actions/reports/2015/SKBNJune2015FINAL.pdf

Totten, Samuel. 2012. Genocide by Attrition: the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. Transaction Publishers: New Jersey.

Totten, Samuel and Amanda Crzyb (eds.). 2014. Conflict in the Nuba Mountains From Genocide-by-Attrition to the Contemporary Crisis in Sudan. London: Routledge.

Trimingham, J. Spencer. 1949/83. Islam in the Sudan, London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

UNHCR. 2015. South Sudan Situation: Yida Refugees Camp: Online http://data.unhcr.org/SouthSudan/settlement.php?id=34&country=251®ion=26, accessed November 29, 2015.

UNMIS. 2011. Preliminary Report on violations of international human rights and humanitarian law in Southern Kordofan from 5 to 30 June 2011. Khartoum, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Verjee, Aly. 2011. Disputed Votes, Deficient Observation: The 2011 Election in South Kordofan, Sudan. London: Rift Valley Institute.

Voice of America. 2015. New Fighting Sends Surge of Refugees to Sudan’s Border Region. http://www.voanews.com/content/new-fighting-surge-refugees-sudans-border-region/2655166.html.

Waal, Alex de. 2006. “Averting Genocide in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan”. Social Science Research Council. http://howgenocidesend.ssrc.org/de_Waal2/

——— (ed.). 2007. War in Darfur and Search for Peace. London: Justice Africa.

Winter, Rodger. 2000. “The Nuba People: Confronting Cultural Liquidation”. In White Nile Black Blood: War, Leadership and Ethnicity from Khartoum to Kampala, edited by Jay Spaulding and Stephanie Beswick, 1–3. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press: http://www.occasionalwitness.com/content/documents/Cultural_liquidation.htm

Wood, Elisabeth Jean. 2008. “The Social Processes of Civil War: The Wartime Transformation of Social Networks”. Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 11: 539–561.