The rapid economic liberalisation and ruthless fight against corruption in Georgia – Interview with Dr. Tamara Kovziridze

How to cite this publication:

Fredrik Eriksson (2017). The rapid economic liberalisation and ruthless fight against corruption in Georgia – Interview with Dr. Tamara Kovziridze. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (U4 Practitioner Experience Note 2017:1)

Georgia’s rapid and substantial improvements in controlling corruption in an endemically corrupt society is an exceptional anti-corruption reform success story. As one of the exclusive contemporary achievers in improving the control of corruption, the Georgian reform experience is of particular interest. With so few rapid successes globally, it appears that the exceptional cases may help correct the failed assumptions of today’s dominant reform approaches.

Dr. Tamara Kovziridze was Deputy Minister of Economy between 2004–2008, and Chief Adviser to the Prime Minister and Head of Advisory Group on Foreign Relations in 2009–2012. In 2012, she was the Deputy Minister of Finance and Deputy State Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration. Dr. Kovziridze actively participated in planning and implementation of key regulatory reforms aimed at improving Georgia's business environment and control of corruption, particularly in the economic sphere. Today, Tamara Kovziridze advises Governments of more than ten countries in Central Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe on economic and regulatory reforms in her capacity as Senior Director and partner at Reformatics, a Georgian consulting firm headed by the former Prime Minister of Georgia, Mr. Nika Gilauri.

Dr. Tamara Kovziridze is one of the few that has insights into the thinking behind – and implementation of – the Georgian reforms immediately after the Rose Revolution. I first met Dr. Kovziridze during a workshop I held in Manila in early 2016. She was invited by the U4 workshop host (GIZ) as one of the resource persons. As she shared her experiences and advice with the workshop participants, I was struck by how very radical the Georgian reforms were. Her account of the reforms exposed a very pragmatic approach to address the deeply ingrained corruption and weak governance practices in Georgia from before the Rose Revolution. But as so often happens in formal presentations and settings, there was limited time for a more detailed and fuller narrative that could explain the Georgian government's various contextual considerations, as well as how reforms were led and managed. Anti-corruption reforms are sometimes described in formulaic terms, leaving strategic considerations and implementation factors aside. As we know that successful reforms in one context can rarely be replicated through export to another governance context, there is a strong need to complement the rather narrow focus on formal institutional reform components.

Dr. Kovziridze's presentation in Manila hinted at a departure from the common reform approach by developing a strategy entirely built on in-depth knowledge of the Georgian context. [i] The diagnosis process went further than identifying the forms and prevalence of corruption and the usual weaknesses of formal institutions. It sought to identify how the problems were sustained beyond a focus on technical capacities. Still, the strategic considerations, the factors that informed creative solutions, and the management of the implementation process that then followed remained elusive.

Impressive anti-corruption advances in Georgia

Against the odds, Georgia has made impressive strides in its fight against corruption since the Rose Revolution in November 2003.

Georgia has emerged as one of very few success stories of the recent decade in reducing corruption. Transparency International (TI) currently ranks Georgia higher than EU states like Bulgaria, Greece, Italy and Romania. A quick look at the Global Corruption Barometer by TI reveals this rare feat of rapid and substantial change: in 2004, 69% of survey respondents believed that corruption would increase during the following three years. The following year, that figure was only 11%.

Box 1: Substantially improved rankings

After only five to six years of reforms, numerous international organizations such as the UN, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the World Bank reported the following rankings and results on service delivery and performance of government institutions in Georgia:

- 2nd place in the category of “Improving Service Delivery” in the 2012 UN Public Service Awards.

- 1st place in respondent satisfaction on quality and efficiency of public service delivery in the category of “Official Documents Issuance” (Table 3.3 in Life in Transition Survey 2011, EBRD).

- Only 1% of respondents report that unofficial payments are usually or always needed in the category of “Official Documents Issuance” (Table 3.2 in Life in Transition Survey 2011, EBRD).

- Improvement from 112th place in 2005 to 16th place in 2012 in the Ease of Doing Business ranking produced annually by the World Bank Group.

The figures in Box 1 show not only the speed by which the improvement in control of corruption was achieved. They also reflect qualitative improvements in service delivery and in the business environment. The question is how sustainable these results are over time. The government of President Saakashvili initiated the reforms directly after the Rose Revolution in November 2003 until being replaced in October 2012 by President Margvelashvili's government.

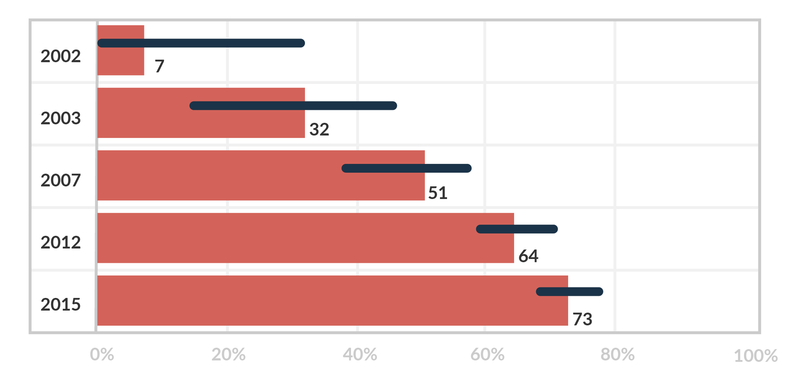

The World Governance Indicators’ Control of Corruption indicator for Georgia from before the Rose Revolution to the shift in government in 2012, and up until 2016, shows that the extraordinary reform results have proven stable after the shift in government (see Box 2) and yielded additional positive effects. The 2017 Ease of Doing Business ranking also confirms that Georgia's ranking appears stable despite an increased number of countries measured. In other words, so far the impressive results seem to have survived a shift in government.

Source: The World Bank Group. The bars indicate the percentage of countries worldwide that rate below Georgia. Higher values indicate better governance ratings. The thin line shows the statistically likely range of the indicator. For more details see endnote [ii]

Globally, despite almost two decades of implementing a specific set of anti-corruption reform policies, [iii] there are very few examples of reform efforts that show any considerable effects on corruption.[iv] The lack of results has of course not gone uncommented. Many have stressed the need for a rethink, both in terms of how to understand what maintains high corruption levels, as well as how to address it.[v] However, Georgia is a notable exception worth exploring.

Dr. Kovziridze, when you presented the Georgian anti-corruption reform components in Manila, you repeatedly mentioned speed and quick results as characteristic factors. From the perspective of the international anti-corruption reform agenda, anti-corruption reforms are often considered to take a long time, far beyond the normal donor intervention cycles. Many anti-corruption experts also advocate the virtue of an incremental reform strategy, with a robust measurement system to assess effectiveness and inform adjustments. The Georgian approach seemed to reject that. Why?

"The Georgian anti-corruption effort was characterized by speed, efficiency and quick results."

The Georgian anti-corruption effort was characterized by speed, efficiency and quick results. And those are characteristics that are often aspired to but rather seldom achieved by leaders worldwide.

But Georgia really managed to transform the urgent need to reform into concrete actions. There were not a lot of strategies, action plans or measurement systems developed. The team of reformers headed by the then President set the precedent of creating strong, non-corrupt institutions in the post-Soviet space. And that is quite an achievement in a region where vested interests are a common feature of political processes, and political leaderships are often corrupt. Add to that populations that are accustomed to corrupt practices, who have never experienced government institutions working differently.

Given the Georgian success, it seems to me that Governments who say they want to fight corruption but do not achieve it, do not really mean it and therefore do not give implementation an honest effort. It has even become fashionable these days to declare a fight against corruption, but as you know, success stories are few. The Georgian Government however, said it, meant it, and actually did it. And while doing so, it was convinced that it had no more time to lose, and so urgent action was needed. Let us not forget that the Government came to power after the Rose Revolution, which was preceded by an anti-corruption campaign by the opposition at the time. In other words, the sense of urgency for reforms was felt among the population as well, which gave the post Rose Revolution Government a strong mandate for bold and comprehensive reforms. This genuine sense of urgency drove the reform process and conditioned the speedy approach. Most frequently, actions were agreed verbally and implemented without any written guidelines. Instead, a Government decision or a short decree was adopted sometimes to formally identify the institution in charge as well as the reform timeline. However, although speed does not guarantee success, it helps to secure continued support in such turbulent times as following a revolution.

"Because results were quick, the public started to appreciate the tough reforms."

Because results were quick, the public started to appreciate the tough reforms. Had it taken long, reforms would have become unpopular. As for donor involvement and analysis by external experts, it should also be mentioned that Georgia very much concentrated on the analysis of its own corruption problems and designing ‘made in Georgia’–approaches. Although some of the approaches might not have been appreciated by our external partners, the results definitely were.

Can you give an example of such a ‘made in Georgia’–approach?

Well, in some cases, creative solutions were found to move corrupt practices into the legal sphere. For example, most people were paying a bribe to obtain a passport or any other document that they needed urgently and were not ready to wait for. Basically, public expectations of slow services and corruption meant that they were ready to pay extra for quick “services”. Subsequently, the public service delivery system was reformed in such a way that a fee-based service delivery was introduced: quicker services cost more, while services provided within a standard time are provided against an affordable fee or free of charge. Today, an international passport can be obtained within a day if a higher fee is paid. In addition, it is delivered in modern facilities were average servicing time is approximately no more than five minutes. And in stark contrast to before, applicants are greeted by government employees like clients that leave the facilities happy.

If you were to define the fundamental principles of the Georgian reforms against corruption which you believe were essential to achieve success, what would they be?

I think, looking back, there are two important rules that emerge from the Georgian experience. Firstly, all this success was possible in Georgia under one important precondition: the top leadership was non-corrupt. The rule-of-thumb is that if elites remain corrupt no country can really defeat corruption.

"The rule-of-thumb is that if elites remain corrupt no country can really defeat corruption."

Secondly, the fight against corruption was a cross-cutting objective in all reform areas, ranging from tax and customs reforms, labor legislation, business licenses and permits, healthcare reform, education reform, etc. This means that the Georgian anti-corruption agenda comprised all spheres of economic and social life, rather than an anti-corruption agenda as such, isolated from economic and social reforms.

That second rule is very similar to how the Scandinavian countries increased control of corruption. Originally, there was no specific anti-corruption strategy or institution set up to turn things around. Rather, the entire formal institutional system incorporates preventive principles throughout. But the first rule you mention may perhaps need some further explanation. In contexts where corruption is the norm and not the exception, it is highly unlikely that anyone is untouched by corruption. Particularly if they emerge from within the existing political system. So, I suppose you are saying that if the ruling elites do not want change and do not accept the loss of any potential vested interests due to that change, progress should not be expected? Or would you say that the desire for change and acceptance of loss must apply also to other elites, such as the economic elite?

I actually mean government elite, whether in charge of political, social or economic matters; those who are responsible for defining and implementing policies. One fundamental feature of the Georgian story is that the success in fighting corruption was preceded – but also made possible – by the almost complete replacement of the political elite. Those who did not embrace the policy of change, or were obstructing it, were replaced by new, young and motivated individuals with no links to corrupt practices. This is essential for defeating corruption. All the more so in countries where mentality and educational gap is immense between generations, like it is in the post-Soviet space.

I remember you mentioned a very radical measure that really drove home the point of developing homegrown policies based on a deep understanding of how formal institutions really function. Basically, where the harmful informal practices of the formal institutions outweighed their benefit to the public, the government shut them down. Can you describe the considerations that led to such decisions?

A corruption-free environment requires strong institutions. If we look at top performers in international corruption studies and surveys, these are typically countries with well-developed and stable institutional structures, which build the foundation for non-corrupt governance. As it takes time to build institutions, it is widely perceived that the fight against corruption takes time as well. But the Georgian reforms were based on a very special and radical approach towards dysfunctional institutions. Institutions and their functions were often entirely abolished rather than changed and reformed.

"Institutions and their functions were often entirely abolished rather than changed and reformed."

This happened in cases where informal corrupt practices clearly outweighed the formal role or benefit of the institutions. Such institutions were weak and inefficient, so there was little need or benefit to keep them as they were. Importantly, the Government dramatically objected to the argument often brought by bureaucrats – “if we abolish this institution, everything will collapse”. The Government did not shy away from this bold step.

But there were also radical measures taken within the formal government institutions that remained as well?

The informal practices mentioned above were deep-rooted, often having a history of several decades. Informal practices, for example in the form of informal payments and bribes, was a huge cost for the economy as businesses and citizens had to carry those costs. But it was also a cost for the government in the form of lost revenues due to the shadow economy and informal activities.

The corrupt practices in the formal institutions were conditioned by two main factors. The formal rules of the game were prone to corruption, and there was a corrupt mind-set shared by employees and managers. Therefore, I think it is possible to say that there are two main features that contributed to the quick delivery in the fight against corruption in Georgia. As mentioned, one was this outright abolition of institutions instead of a gradual reform of institutions and their rules of the game. The second feature was the dismissal of all, not just some, individuals in charge of informal and corrupt practices in remaining formal institutions. The approach was rather radical. Commonly, a new head of agency or minister was appointed with a broad mandate to undertake structural and personnel reforms aimed at quick results. Such newcomers might have had little experience in the field, but the right attitude towards reforms and no links to corrupt practices. These were often western-educated individuals. So, a large number of civil servants were simply dismissed, which was a very painful and unpleasant process, although key for reform success.

How was the risk of resistance from vested interests managed when deciding to shut down entire institutions? And how did the public respond?

To give you a straight-forward answer, these vested interests were simply ignored. But again, to do so you need un-waivering and consistent commitment from the highest political leadership. I served about nine years in the Government and was entirely free to choose my staff. Whenever I had a reform idea, most of the times, I felt great support from the leadership, not shying away from change, even at the cost of offending and dismissing corrupt individuals.

For example, in 2004 we were reforming the system for issuing export certificates. Up to 20 people were working in the responsible unit, and the costs for exporters to obtain this certificate in the form of money for bribes, delays, and time spent on visits to the Ministry were much too high. In short, there was no effort from the Government to facilitate exports by keeping transaction costs low. After the reform, two employees were doing the same job previously done by 20, and only one day was needed to obtain the certificate. All other employees were dismissed, and the salaries of the remaining ones were substantially raised. During the reform, I was approached by friends and relatives of the dismissed officials trying to convince me that they should be allowed to stay. I just disregarded them while knowing I had the full backing by my Minister at the time.

But besides disregarding vested interests, one important feature that distinguished the Georgian anti-corruption reforms was that they were by no means bureaucrat-driven. On the contrary, they were mostly championed by persons who had no prior affiliation with Government institutions. Often, they had little or no detailed knowledge of how the institutions functioned. This pre-empted the existence of vested interests.

"You cannot fight corruption by placing in charge the same corrupt individuals but giving them a different instruction."

You cannot fight corruption by placing in charge the same corrupt individuals but giving them a different instruction. Unfortunately, this is what most countries do. In corrupt environments officials in charge try to please others through, for example, offering jobs in key positions. They know that one day they will ask reciprocal “service” from such individuals. In Georgia, in contrast, the newly recruited young elite cared about the change and not about other individuals and their benefits.

This question of vested interests and institutional resistance to reforms is of course a problem for a reform-minded government in many ways. A population used to very high levels of corruption have expectations of corrupt behaviour, both by the bureaucracy as well as by citizens. Somehow, any real change must be demonstrated and communicated to the public so expectations can change, and hopefully also the behaviour of people interacting with the bureaucracy. In the Georgian case, that communication of change was not left to waiting for a change in the conviction rates for corruption, hoping that that would change expectations after a few years. Nor did you stop at communicating new laws and regulations, hoping that they would also be effectively implemented. Both those typical approaches to communicate reform results rely heavily on the willingness of the judiciary and the bureaucracy to support the reforms. How did the Government approach communication of change?

Yes, there was a strong need to communicate that the Government was delivering the change advocated for during the Rose Revolution. To demonstrate the Government's attitude to the broader public and make it very clear that the time of nepotism and corruption was over, there were cases when arrests were broadcast through media. Moreover, when a corruption case was found among officials serving for the Government, that was an opportunity to discuss it publically and broadcast those discussions widely.

"The approach was ruthless and the same rule would apply to everyone without any exceptions."

The objective was to make clear that no one would be pardoned or shielded in case of corruption and that the Government was committed to this change. Some of our external partners may have criticized such approaches, but at the end of the day they worked. The approach was ruthless and the same rule would apply to everyone without any exceptions.

Another typical anti-corruption reform component concerns raising public sector salaries in order to remove the incentive for the so called ‘needs-based’ corruption. In research, there is ambiguous support for the impact of such measures on corruption. Was that also a component of the Georgian public sector reforms?

Yes it was. But the rationale was not only to remove the incentive of ‘needs-based’ corruption but also to satisfy the human resources needs. Salaries in the public sector increased by about 15 times on average, within a short time after the start of the reform process. I will give you my personal example. When I joined the Government as Deputy Minister of Economy in 2004, my initial remuneration was less than 100 dollars a month. Prior to joining the Government, I had studied and worked in Europe (Germany and Belgium) for almost eleven years. My motivation to join the Government was to participate in this important transformation that was taking place in Georgia, as I saw a realistic chance of positive change in my country. Had the remuneration not been increased to a decent level, I would not be able to stay in this position, let alone have a motivation to participate in the reform process. This remuneration reform happened quickly, within a couple of months after the change of Government following the Rose Revolution. It was very clear to the Government that otherwise it would be impossible to attract and retain qualified individuals and fight corruption.

One factor that is very rarely covered in the research on anti-corruption reforms is the quality of leadership. We see lots of research and recommendations on reform components, policy principles and scope, but the issue of leadership remains elusive. Can you tell me a little about what you perceived as being the leadership qualities that brought progress in the reforms? And do you think they would be useful in other country contexts as well?

Personalities do make a difference. Committed, consistent, radical – in a healthy way– and result-oriented leadership is key.

Any fight against corruption will most likely fail if the process is bureaucrat-driven, and if the political leadership is not involved in this fight itself. It is important to stress that although formal institutions might be key to anti-corruption reforms, personalities and leadership teams are of utmost importance.

The Georgian anti-corruption reforms were characterized by a number of features as far as the leadership role is concerned. There was top-down coordination by the leadership. And there was no chance for mid- or low-level bureaucrats to block key reforms because of corrupt motivations. Also, the leadership strongly encouraged a healthy competition amongst government members for reform ideas by promoting reformers. And another important feature was this non-reliance on bureaucrats, as I mentioned earlier. Ministers were often acting as technocrats and following the reform to the smallest level of detail to ensure progress and success. This might not be an exhaustive list, but they were definitely important.

You have said that the main priority for the reforms was to strengthen the Georgian economy. For me, this rings a bell. Current research seeking to identify the factors that contributed to increased control of corruption in recent times highlights the pursuit of neoliberal economic policies, where increased control of corruption appears to be an externality. In the Georgian case, was the choice to focus on the economy a strategic approach to address corruption in order to win the support of powerful economic elites, and maintain the backing of the public demanding economic reforms? Or was the reduction of corruption more of an externality to the priority of strengthening the Georgian economy?

Georgia is a small country which has neighbours that are either large markets and thus attractive for investment, such as Turkey, or they are rich in mineral resources, such as Azerbaijan. Given that Georgia does not have any of those assets as a basis for economic growth and development, but is located on a transit route between Europe and Asia, the Government decided to transform the country into a regional trade, transport, investment and tourist hub with easy and simple rules. The Government identified a corruption free environment as a key feature and competitive edge of such a hub, especially in a region where most countries perform poorly in terms of corruption.

With this in mind, the Government conducted a series of reforms focusing on establishing a business-enabling environment, creating a strong comparative advantage for the Georgian economy both regionally and globally. This objective might sound logical and maybe even banal, but international experience shows that in many countries great objectives are declared but poor results achieved. Georgia is quite remarkable in this sense.

But to answer your question whether economic reforms were chosen as a strategy to address corruption, or if anti-corruption effects was a mere externality of economic reforms, I have to say neither. The economic reforms would not have been successful without anti-corruption efforts in these areas. And on the other hand, there would be no successful fight against corruption without drastic economic liberalization in the form of deep-going deregulation. Increasing or maintaining excessive state regulation at the same time as fighting corruption would have been a counterproductive and inefficient effort.

I guess it is possible to say that the reforms created a virtuous circle. The Georgian liberal economic reforms resulted not only in growth, increased export and investment. They also led to the emergence of a middle class as well as a business sector, which saw the economic opportunities for themselves in a deregulated, corruption-free market. That reinforced their support of the economic reforms.

In your view, what parts of the economic reforms do you think had the greatest impact on corruption in Georgia and why? Slimming the public sector, stronger role for business, reduction of regulations, improved transparency or other similar measures?

I think the Georgian reform process was successful precisely because reforms were done in several areas in parallel. So, there was a concerted “attack” on corrupt institutions and processes. The objective was to create small Government, open and free market environment and growth driven by private sector. That way, Georgia would function as that regional hub for trade, transport and investment we set out to achieve. No one single reform played a key role, instead they all complemented eachother.

"Governments fail to deliver results because they shy away from drastic measures and choose to adopt a phased or a sector-by-sector approach."

Governments fail to deliver results because they shy away from drastic measures and choose to adopt a phased or a sector-by-sector approach. This way corruption is maybe somewhat mitigated in one area, but still persistent in the other, not changing the overall picture.

In my view, in Georgia, the reform of tax legislation by reducing the number of taxes from 21 to 6 was as important as the establishment of the customs one-stop-shop, and the 85% reduction of business licenses and permits. Equally important was the reform of the energy sector, or the introduction of ‘silence is consent’-principle in Government service delivery. For example, in the energy sector, a drastic turnaround was possible, among others, because corruption was rooted out. Subsequently, a country with almost permanent black-outs was transformed into a net electricity exporter to all its neighbours within two-three years.

This simultaneity of reforms was key to success, and the transformation in many areas in parallel was an important factor conditioning success. They all need to be seen as reinforcing and contributing to the necessary transformation. Picking one or a few would not have achieved the same success.

In what way do you think the reforms impacted on corruption in Georgia?

The reform policies in Georgia, including in the economic sphere, were characterized by a number of horizontal principles applied across different areas. Their purpose was to simplify and streamline government for business and citizen interaction. I mentioned the the ‘silence is consent’–principle, which means that if state services, e.g. licenses and permits, are not delivered within a legally defined deadline, the state service is automatically granted. So, the regulation favours the applicant and no longer civil servants and their vested interests. This way, civil servants lost the possibility to extend delivery time and ask for bribes in exchange of accelerated services.

Another principle that I mentioned before is the ‘fee for speed’–principle. A service fee depends on the speed of service delivery, e.g. delivery within a day costs more than standard delivery of services. This principle is applied to services in various areas ranging from registration of a company to obtaining an ID and passport documents.

There is also the ‘one government’–principle, which was key to increasing the efficiency of government institutions and eradicate corrupt practices. The principle means that no government agency can request of a service applicant to provide documents from another government agency. Thus, no time is wasted on going from agency to agency and no money is spent on acquiring government generated documents separately. All government agencies have access to the same applicant-related information, which removed a previous cause of inefficiency and many opportunities for corruption.

Then there is the ‘regulatory guillotine’–principle, which was another tool to fight old-fashioned Soviet-style regulation prone to corruption. It meant that a deadline was introduced for the Government to identify all the necessary legislative acts. As a result, more than 1500 regulations were abolished in Georgia right after the deadline.

These principles contributed to the re-engineering of institutional processes in such a way that they prevent corruption. On the other hand, incentives were created for civil servants to act in an efficient and client-oriented way. Such incentives are among others various bonus systems as well as increased salaries of civil servants.

So, there seems to have been a strong service principle at the heart of reforms as well, considering the focus on efficiency and client-orientation in the civil service. True?

Absolutely. The Government decided that the state should treat its citizens like clients and even compete with the most qualified private sector representatives in terms of efficiency in providing various services. To introduce this citizen-driven rather than bureaucracy-driven approach, the existing legal and institutional environment was reviewed from the point of view of recipients of Government services, followed by necessary improvements. Today, a company can be registered within a day and a property transaction can also be completed within a day. These, and many of the other 450 Government services are delivered at client-friendly Government one-stop-shops, which are located in all major cities of Georgia. The Georgian Public Service Halls are perfect examples of this approach where hundreds of Government services are provided in one space, in electronic form. The average waiting time is five minutes, and the average servicing time only six to seven minutes. Not many countries can match that, certainly not in our region.

When you read about the few successful contemporary achievers in controlling corruption in research, they are often described as having nothing to do with the common anti-corruption reforms that the international community recommends or that you find enumerated in UNCAC. What do you think the international community is missing? What could it learn from the Georgian reforms?

There are many typical problems that obstruct progress in controlling corruption. Often, the same type can be found in different regions worldwide. I have already mentioned the seeming lack of genuine political interest to whole-heartedly take the political risk of addressing corruption in countries where corruption is deeply ingrained. I guess that lack of conviction and genuine commitment may also be explained by a perception that corruption is normal and part of everyday life, which cannot be otherwise. But besides that, perhaps there are a few lessons of the Georgian reforms that can be seen as a corrective to some commonly held beliefs of the international community. One of those beliefs that I think Georgia has dispelled concerns a slow and step-by-step approach. That is also closely linked to an approach to address corruption which is very process-oriented, focusing a lot of attention on concepts, strategies and documentation rather than real actions. The Georgian reforms clearly show that to address pervasive corruption you need strong political leadership that does not delegate reform responsibilities and rely on the bureaucracy to take reforms forward. A hands-on personal engagement in reforms with a highly technocratic role appears to be the type of leadership required. Another feature which does not seem to be represented in the standard anti-corruption recommendations of the international community is the importance of a reform-minded team which is not scared of innovative approaches and radical change. That unflinching reform commitment can only exist if they have nothing to lose if corruption is gone and therefore have no interests in preserving the existing structures.

So, with these lessons from the Georgian reforms, do you think the international community can become more successful in providing recommendations and offering support to anti-corruption efforts?

International community recommendations – even though based on common sense and best intentions – are often powerless in specific country contexts. In my view, this is because to successfully defeat corruption, you need the right combination of factors on the ground. The key factors I have already mentioned, but I also think the right moment matters. The post-revolution period provided a very strong popular mandate for the Government, paving the way for radical reforms. They were both expected and welcome. That moment of strong popular support may possibly be created by national leaders or some particular corruption scandal, without a revolution. Still, without strong popular backing, the scope that remains for reforms is probably an ineffective piecemeal approach.

But importantly, based on my practical experiences, I do believe that a successful fight against corruption is much more efficient when it happens in parallel with an economic liberalization and deregulation agenda. The fight against corruption is at the same time a fight against unnecessary regulation, Government requirements and institutions. The international community was at times sceptical towards Georgia’s radical liberalization and drastic institutional measures, but as results were quickly visible, the attitudes towards our reforms changed gradually.

Finally, I just want to touch very briefly on the issue of critique against the government that initiated the reforms. In the context of a revolution, it is unlikely that a transition towards improved governance will not encounter resistance and as a consequence, outright government and economic dysfunction to various parts. The question then comes up what a legitimate way to handle such circumstances is. Personally, I have come across statements dismissing the value of Georgian reforms due to various critiques of how some politically volatile situations were handled. What do you think about such statements? Is the value of the Georgian reform achievements as regards control of corruption nullified by circumstances surrounding the wider societal and political transition?

For me, a real fight against corruption is associated with radical and dramatic reforms. I do not believe that one can exist without the other. The fact is that almost all countries worldwide undertake some effort to fight corruption or at least declare to do so. Very few of them have a real success story to tell, let alone a low-income country with fundamental developmental challenges, weak institutions and a fragile economy, such as Georgia immediately after the Rose Revolution.

Some aspects in the Georgian process of fighting corruption may have been criticized, and not all the elements in this process were optimal.

"Georgia managed to fight corruption successfully, while most countries do not."

In many other countries fighting corruption, the same or other types of mistakes are made without any palpable results in controlling corruption. Therefore, let’s measure success by results. Georgia has indeed something to show.

The U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre at CMI works to identify and communicate informed approaches to partners for reducing the harmful impact of corruption on sustainable and inclusive development. Sign up for our newsletter.

Comments and Feedback

We welcome your feedback. Please don't hesitate to send your thoughts to U4 Senior Advisor Fredrik Eriksson.

Or follow us on Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn.

Disclaimer

All views expressed in the interview section of this U4 Practitioner Experience Note are those of the interviewee, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U4 partner agencies, or CMI/U4.

Endnotes

[i] The case of Georgia as a ‘contemporary achiever’ is described in Norad's Contextual Choices in Fighting Corruption: Lessons Learned (Norad 2011a) and in Mungiu-Pippidi's The Quest for Good Governance (Mungiu-Pippidi 2015). The Georgian reforms fit well with the empirically tested Resources and Constraints model, describing the required components for effectively shifting a corruption equilibria.

[ii] Percentile ranks have been adjusted to account for changes over time in the set of countries covered by the governance indicators. The statistically likely range of the governance indicator is shown as a thin line. For instance, a bar of length 75% with the thin line extending from 60% to 85% should be interpreted as 75% of countries rating worse and 25% of countries rating better than Georgia.

[iii] Khaghaghordyan 2014.

[iv] NORAD 2009, 2011a, 2011b; World Bank 2011.

[v] Rothstein 2011; North, Wallis and Weingast 2009; Persson, Rothstein and Teorell 2013; Johnston 2014; Marquette and Peiffer 2015; Norad 2011a; Mungiu-Pippidi 2015; Booth and Cammack 2013; Khan 2010, 2012.

References

Booth, D. and D. Cammack (2013) Governance for Development in Africa: Solving Collective Action Problems. New York: Zed Books.

Johnston, M. (2014) Corruption, Contention, and Reform: The Power of Deep Democratization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Khaghaghordyan, A. (2014) 'International Anti-corruption Normative Framework: the State of the Art. Project deliverable for the European Union funded research project ANTICORRP'.

Khan, M. (2012) Beyond Good Governance: An Agenda for Developmental Governance. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Khan, M. (2010) Political Settlements and the Governance of Growth-Enhancing Institutions. DFID Research Paper on Governance for Growth. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Marquette, H. and C. Peiffer (2015) Corruption and Collective Action: Shifting the Equilibrium? Research Paper No. 32. Birmingham: Developmental Leadership Program, University of Birmingham.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015) The Quest for Good Governance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Norad (2009) Anti-Corruption Approaches –A Literature Review. Oslo: Norad.

Norad (2011a) Contextual Choices in Fighting Corruption: Lessons Learned. Oslo: Norad.

Norad (2011b) Joint Evaluation of Support to Anti-Corruption Efforts, 2002-2009. Synthesis Report 6/2011. Oslo: Norad.

North, D; Wallis, J. and B. Weingast (2009) Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Persson, A.; Rothstein, B. and J. Teorell (2013) Why Anticorruption Reforms Fail – Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem. Governance 26(3): 449-471.

Rothstein, B. (2011) The Quality of Government. Chicago: Cambridge University Press.

World Bank (2011) World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2012) Doing Business 2012: Doing Business in a More Transparent World. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2017) Doing Business 2017: Equal Opportunity for All. Washington, DC: World Bank.