Prospects for peace in a petro-state: Gas extraction and participation in violence in Tanzania

The link between unmet expectations and violent civil unrest

A survey experiment: Manipulating expectations about petroleum revenues in Tanzania

Limited desire to participate in violence

How to cite this publication:

Andreas Stølan, Benjamin Engebretsen, Lars Ivar Oppedal Berge, Vincent Somville, Cornel Jahari, Kendra Dupuy (2017). Prospects for peace in a petro-state: Gas extraction and participation in violence in Tanzania. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2017:10)

Significant petroleum discoveries in Tanzania have shaped the country’s political discourse in recent years, with politicians promising to turn this newfound resource wealth into rapid economic growth and poverty reduction. Large-scale extraction of petroleum has yet to occur, however, raising fears that creating unrealistic expectations about future economic gain could motivate citizens to participate in violent collective action if these expectations are not met. Deadly riots in the gas-producing Mtwara region in 2013 over dissatisfaction with a planned gas pipeline route demonstrate that these fears are not unfounded. However, while this incident should be taken seriously, it is does not necessarily indicate that Tanzanians are willing to take part in future protests or other violent actions against the government. We review evidence from a recent survey experiment that shows that petroleum-related expectations are not very likely to inspire large-scale participation in violence.

The link between unmet expectations and violent civil unrest

A large scholarly literature on the connection between resource wealth and violence generally concludes that high-value resources like oil, natural gas, and minerals and metals can fuel violent, armed conflict and sustain it (Ross 2015). Resource wealth has been statistically linked both to the onset of armed conflict and its duration, with scholars arguing that people take up arms either because they are upset over how government or private companies are (mis)managing resources and their revenues, or because they want to control resource revenues for their own personal benefit.

“Mtwara will be the new Dubai”

– President Jakaya Kikwete, 2010

But in the case of Tanzania, where petroleum resources have yet to be fully extracted, could expectations about the future management of oil and gas motivate people to engage in violence? One theory that can explain how expectations may motivate people to join a politically-motivated armed conflict aimed at the government is Ted Gurr’s relative deprivation theory. This theory states that the greater the mismatch between what people believe that they deserve or expect that they are rightfully entitled to on the one hand, and what they are actually capable of attaining and maintaining on the other hand, the greater will be their discontent or frustration. The greater the levels of frustration, and the higher and more widespread these feelings are, the greater the likelihood for violent conflict to break out. Key to the theory is the idea that people compare the status of their social or cultural group to that of other groups in society, and that these feelings of deprivation reflect subjective feelings, not necessarily absolute material deprivation (Gurr 1970). Those who feel they are worse off than other groups are likely to resort to violence. The novelty of Gurr’s theory is its insights into why people participate in collective violence. That is, since politically-motivated violent conflict occurs between organized, identifiable groups in society rather than random individuals, we must understand how groups of people decide that the use of violence is a legitimate way to resolve disputes.

“Unmet expectations about benefiting from future petroleum revenues could encourage individuals to participate in violent action against the government”

While relative deprivation theory provides an intuitive and well-reasoned explanation for how and why economic or other social inequalities can lead to violence, it is hard to predict when, exactly, shared feelings of disadvantage and dissatisfaction will turn violent. Here, collective action theories challenge the idea that emotions are sufficient to persuade people to engage in actions that are extremely costly for individuals. A good cause is rarely enough to spark large-scale group action, violent or peaceful, since such behavior is very risky (Olson 1965). Instead, groups must motivate members to undertake collective action by providing them with material or social benefits (i.e. wages, food, social status, or power) or by punishing them for breaking the rules. This is especially true in the case of violence, given that individuals risk death, imprisonment, and social, political, and economic exclusion for their participation in actions that directly and violently challenge the government. In other words, it is likely much more difficult to convince people to be violent for political reasons than established theories suggest.

A survey experiment: Manipulating expectations about petroleum revenues in Tanzania

To better understand whether expectations can influence individuals’ likelihood of participating in violence, we carried out a survey experiment in Tanzania, where politicians have openly raised citizen expectations about the benefits of petroleum extraction. 3060 individuals from Dar es Salaam and the gas-producing regions of Lindi and Mtwara took part in the study. The study randomly exposed the participants to different political discourses and information related to petroleum exploration, and then assessed how this exposure influenced their views of joining violent, collective actions like protests and riots aimed at challenging the government. Figure 1 depicts the text that was shown to the study participants and Figure 2 shows which groups received particular treatments.

Figure 1: Treatment scripts

Script 1: Tanzania has discovered large amounts of natural gas offshore in the regions of Mtwara and Lindi. Some politicians have previously stated that these gas resources could generate very large revenues and many new jobs, and that the gas resources could transform Tanzania into a much wealthier country. One leading politician recently stated that “the government have embarked on a grand plan, and Tanzanians in general should expect economic revolution in few years to come.”

Script 2: Today, Tanzanian future gas benefits and revenues are in reality very uncertain. According to some recent estimates, if the status quo continues, there could in fact be very modest revenues, or perhaps even no revenues, from gas extraction.

Script 3: One reason for the low potential revenues is that gas revenues are often poorly managed, weaken the government bureaucracy, and lead to a more authoritarian state. Potential incomes and benefits then become much smaller than what they could have been.

Script 4: Moreover, gas revenues are often unequally distributed between regions. A few individuals, often those who are already rich, typically become even richer, while the majority does not benefit much, causing overall inequality to rise.

Note: The scripts were administered in Swahili. We report here the English translation.

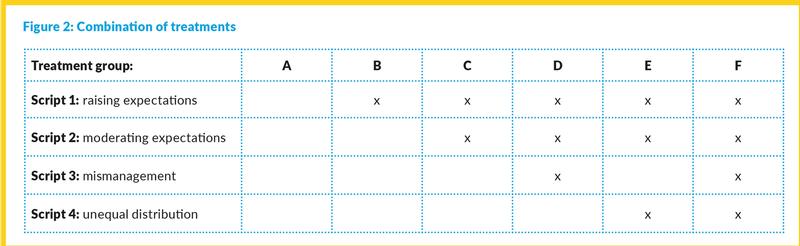

Figure 2: Combination of treatments

The analysis proceeded as follows. The survey answers of Group A – who was not provided any information – was compared to Group B, who read Script 1, which was designed to raise expectations. To assess how the current uncertainty about future petroleum revenues might shape perceptions and thus propensity for violence, Group C read both Scripts 1 and 2, and their responses were compared to Group B. To assess the influence of mismanagement of the petroleum sector, Group D read Scripts 1, 2, and 3. Group E was given Scripts 1, 2, and 4 to judge the effect of the petroleum sector increasing income inequalities. Finally, Group F was presented with all four Scripts.

Limited desire to participate in violence

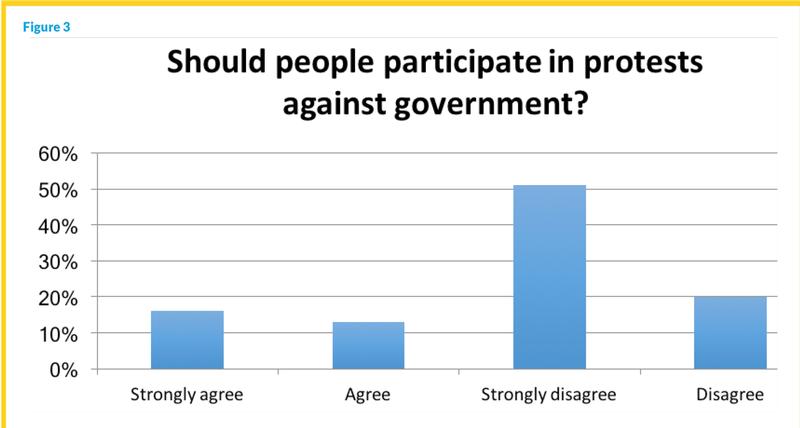

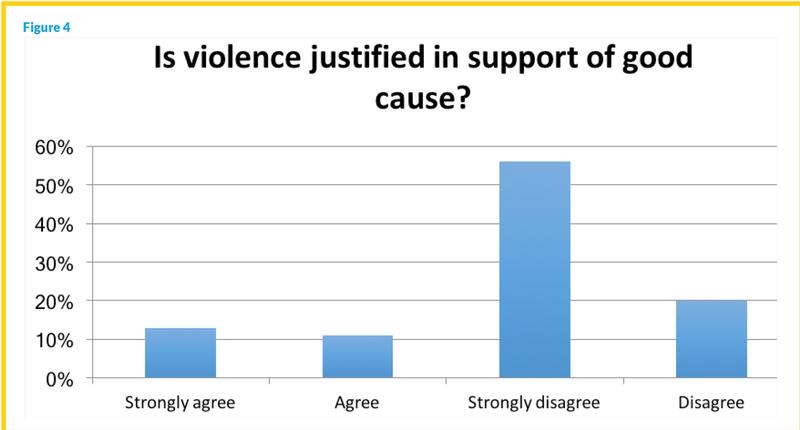

The main findings of the survey experiment are that most participants disagreed with participating in violence against the government, even after being provided with information that tried to change their expectations about benefiting from future petroleum revenues. Figures 3 and 4 show how respondents answered questions about their attitudes towards violence after being exposed to the information treatments. 70% of respondents from the entire sample stated that they disagreed with participating in protest, while 76% agreed that violence should not be used to support even a just cause.

In line with the conflict literature’s findings that people in certain demographic categories are more inclined towards violence, we also correct for relevant respondent background characteristics such as gender, level of education, geographical origin, and other relevant factors. However, even after controlling for these factors (that is, holding them constant), we continue to find that the majority of respondents do not favor using violence, even after raising their expectations about future petroleum revenues.

Implications for petroleum management

Our study challenges the notion that people are relatively easy to motivate to participate in violence, particularly when there is a sense of shared injustice. Violence is a rare event, especially organized and politically-motivated violence in the form of riots, protests, and armed conflict. As other work on petroleum-related violence and expectations argues (see Must and Rustad 2016), expectations about what people deserve and what they are likely to receive are not sufficient on their own to convince people to act violently against the government. It is likely that a combination of emotional and material conditions must be in place in order to do so. Furthermore, political elites and conflict entrepreneurs must create and raise expectations by crafting convincing narratives around injustice. Expectations can, however, be tempered by access to alternative sources of information. Providing citizens with thorough and updated information about the natural gas sector can help them to make better informed choices and reduce expectations, lowering the risk of violence breaking out due to unmet expectations.

References

Gurr, T.R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ross, M. L. (2015). What have we learned about the resource curse? Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 239–259.

Must, E., and Rustad, S.A. (2016). Perceptions of justice and violent mobilization: Explaining petroleum related riots in southern Tanzania. Oslo: Peace Research Institute of Oslo, Conflict Trends brief 06/2016.