Turkey`s international relations

Turkey’s international relations – taking stock

Turkey’s relations with Russia; Is Turkey turning towards the East?

Turkey's relations with the US

Problems with the US Congress.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)

Syria: Disengagement and Pullout

Changing perceptions in the US?

Turkey's relations with the EU

Turkey’s stance towards the Assad regime

Turkey versus YPG/PKK in Syria: Strategy and tactical moves - Constraints by other actors.

How to cite this publication:

Siri Neset, Chr. Michelsen Institute, Metin Gürcan, Episteme Turkey, Hasret Dikici Bilgin, Istanbul Bilgi University, Mustafa Aydin, Kadir Has University, Arne Strand (2019). Turkey`s international relations. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2019:2)

Introduction

This CMI report takes a snapshot of a few of Turkey’s most important international relations and vital issues that frame these relationships. Obviously, this report cannot cover everything, as Turkey is a dynamic international actor situated in the center one of the world`s most fluid regions, where the situation both in the region and also within Turkey itself can change and does change from one day to another.

Additionally, the structures and processes of foreign policy decision-making within the Presidential System are new, and the effect that this has on the development of foreign policy in “New Turkey” needs more attention and research. The aim of this part of the study has been to take stock of (some) of Turkey`s international relations and the Turkish perspective on international issues that impact upon these relations, to put all of this into an analytical and theoretical context, and finally to identify some directions of future developments. The study is based on desk studies, the author’s collective knowledge, as well as conversations with our networks within Turkey. Fieldwork and consulting with networks was conducted in November- December 2018 and the report written in January – February 2019.

Turkey’s international relations – taking stock

To narrow our focus at the outset of writing this report the authors discussed what we thought would be the top targets for Turkey’s foreign policy moving forward. At the top of our list was Russia, because of the multifaceted strategic partnership Turkey has with that country. Next on our list was the United States of America, thanks to the longstanding, but difficult, alliance Turkey has with the US. Third, we expected that the Mediterranean situation would intensify and therefore that the countries involved would demand Turkey's attention. Finally, European countries would still be important to Turkey, especially with regards to the economy.

We decided to discuss Turkey's regional aspirations within the contexts of (1) the case of Syria, (2) the politics of the Eastern Mediterranean, and (3) the politics of the Black Sea Region. In the upcoming conference at Chr. Michelsen Institute, we will discuss more comprehensively Turkey's regional aspirations, its positions towards other regional actors such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, and its position with respect to regional struggles and ideological foundations (such as for example, Eurasianism, Islamism etc.).

We also discussed what issues might impact Turkey's relationship with other countries. Here, the Kurdish issue stands out as the top issue to impact upon Turkey's foreign relations, especially in the context of the Syrian war and Turkey's cross- border fight against PKK and the definition of YPG as PKK’s partner. Thereafter, energy is one topic that impacts relations with the US (over Iranian gas/oil), with Russia (from which Turkey imports most of its oil and gas), and not least with the countries involved in the Mediterranean situation, where the potential for energy exploration and extraction is a large part of the picture. We also anticipated that Turkey’s need for foreign investments would influence Turkish foreign policies. Syrian refugees would also have an impact upon Turkish policies in Syria and also the relationship with European countries, but maybe not to the same degree as before.

Finally, we identified domestic issues that we expect might have implications for Turkish foreign policy. With regards to the national debate amongst the different political parties in the upcoming local elections[1], we anticipate that Turkey's foreign relations would be a contentious issue that would play into the rhetoric, especially from the MHP/AKP camp. The implementation of the Presidential system, especially with regards to the processes of decision-making could be a factor, insofar as the workings between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA ) and the Presidency affects the quality of the information on the basis of which the President makes his decisions. Finally, the ideological struggle on issues such as religion and nationalism, and between AKP and MHP on foreign policy issues, could also be influential and set constraints upon the preferred policies of the President.

Turkey’s relations with Russia; Is Turkey turning towards the East?

“Turkey’s relationship with neighboring Russian Federation will remain as one of the fundamental elements of our foreign policy”. These were the words of Turkey's Foreign Minister at the Ambassadors’ Conference in August 2018,[2] and they highlight the importance of Russia’s relationship to Turkey. Nevertheless, the Foreign Minister continued to point out that Turkey would not stand back from addressing issues of disagreement.

Russia has been classified as a strategic partner (not an ally) to Turkey, and cooperation with Russia is and will remain for the foreseeable future especially important to Turkey with regards to Energy, Trade, and the Syrian conflict. Presently, the planned purchase of S-400 Triumf (SA-21 Growler) medium range ballistic missiles and air defense systems is also framing the relationship and has become an area where Turkey needs to balance Russian interests and demands with those of NATO. In the Black Sea region, Balkans, Central Asia, and the Caucasus where Russia and Turkey have competitive and often conflicting interests the relations, it is important for Turkey to get insights into Russian thinking and maneuvering. Turkey's East/West balancing is a difficult factor in Russian-Turkish relations and one where Russia has much to gain by splitting Turkey from its western allies and alliances. Moving forward Russia’s growing influence in the Mediterranean might also provide a source of concern for Turkey. Below we present a discussion of some of the major issues in Turkey-Russia relations: the nature of the partnership, trade, defense and security, energy, and the Black Sea Region. East/West balancing and the Mediterranean will be discussed later in the report.

The nature of the partnership

The relationship between Turkey and Russia is characterized by being an elite-driven process mainly shaped by the agencies of Erdoğan and Putin, meaning that it is not institutionalized. We observe some sort of a “strongman brotherhood” between Putin and Erdoğan, creating a unified front against Western criticisms regarding their domestic and foreign policies. Yet, this brotherhood lacks institutionalization/institution-building mechanisms in the sphere of economy (particularly energy, agriculture, tourism), defense, and security. It is also the case that the relationship has a short term focus, issues of discussion are time-framed around weeks rather than years, the relationship is pragmatic, both actors prioritize their self-interest first, and the relationship is characterized by a mutual reactionist attitude towards the West, where the EU and the US are of main concern.

Despite it being driven by elites, short-termist, pragmatist, and reactionary, the relationship between Turkey and Russia has been growing stronger. In Ankara’s bureaucratic circles, Russia’s influence is increasing. Also note that Russians know very well how to “empower” those pro-Russian actors/groups and networks in Turkey in the eye of state’s bureaucratic cadres. However, we have serious doubts as to what extent these institutionalization efforts would yield a long-term strategic alliance between Turkey and Russia in the near future.

In Ankara the strategic thinking seems to be revolving around the need for diversification of economic and strategic ties to soften the impacts of deteriorating relations with the Western block and to sustain Erdoğan’s rule in Turkey.

Turkey and Russia’s strategic relations have grown closer in four distinct ways.

First, relations between Turkey and Russia have slowly grown in response to Turkey’s disengagement (rhetorically) from EU, NATO and the US, particularly since the failed coup attempt. Immediately after the coup, Erdoğan received strong support from Putin, in contrast to what was seen as half-hearted support from Western countries. Although US leadership has rejected the accusations, AKP cadres remain skeptical of US involvement in the coup attempt. This critical issue has given Russia much leverage in strengthening its ties with Turkey.

The second way is future defense cooperation between the two countries. In late 2017, Turkey’s Presidency for Defense Industries, now directly attached to the presidential palace, announced that it had signed a contract with a Russian defense firm to purchase two S–400 air defense systems. The agreement received disapproval from the West, particularly the US, which criticized Turkey’s shifting toward Russia’s sphere of influence. The main problem is that the S–400 is not integrated into NATO’s defense systems. Here, Putin’s game plan might be, through the debate about the defense cooperation between Ankara and Moscow, to keep Ankara questioning its traditional NATO-centric geostrategic orientation so as to hold the Western security bloc in a chronic stalemate on the southern flank.

Third, economic parameters also play a huge role in the Turkey-Russia relationship. Turkey is Russia’s second largest natural gas market after the EU. For Russia, Turkey offers an alternative gas transportation route for Russian gas to going through Ukraine[3]. In addition to that, Turkey’s first nuclear power plant is being built by Russia’s Rosatom, which is expected to become a significant player in Turkey’s energy sector.

Finally, Moscow’s continuous emphasis on its regional Kurdish vision is respectful of the existing political borders and sovereignty of the host states of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Moscow has not established military ties with the YPG in Syria, and this fact, together with Moscow’s assurances to resolve the center-periphery problem between Damascus and the Syrian Kurds through a form of regional autonomy limited by a new constitution, would seem to make Russia a more reliable partner for Ankara in Syria than the US.

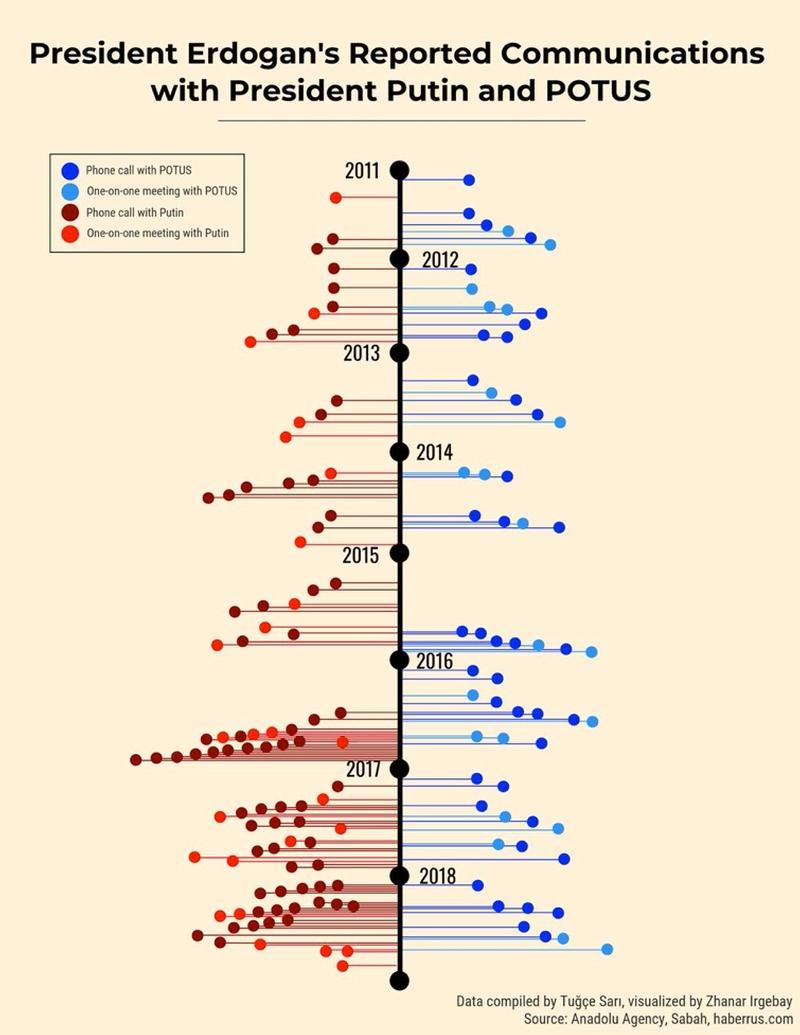

In sum, Turkish relations with Russia are of both great value and a source of concern (which will be discussed below) for Turkey. This relationship has grown to be more important over the recent years, largely due to the geopolitical shifts in the region. An illustration of this is seen in the increasing frequency of contact between Putin and Erdoğan, as demonstrated in the graphic below.

Trade

Before the downing of Russian jet in November 2015,[4] Russia was Turkey’s second largest economic partner, after Germany. Trade, infrastructure, transportation, energy (see below for a separate discussion on this), agriculture, and tourism are pivotal areas of cooperation. Trade barriers between the two countries have been lifted. Turkey was, for example, Russia's fifth biggest trading partner in the first half of 2018, and trade between Turkey and Russia has increased 37 percent year-on-year, reaching $13.3 billion. Turkey's exports to Russia soared 47 percent, while imports from Russia rose 36 percent. As could be seen from the high profile summits between Putin and Erdoğan and the meetings between the foreign ministers, the renewed Turkish Stream Project and the construction of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant are the most important issues. Tourism, where Turkey enjoys a comparative advantage, is also a critical sector for Turkey.

In Moscow’s view, the improvement of trade and economic ties with Ankara is now highly dependent on possible cooperation with respect to critical regional issues, specifically in Syria on one hand, and with respect to energy politics on the other. One should also note that Turkey-Russia bilateral relations on economy are not developing via institutional links, but rather are being steered by the political leaders in Russia and Turkey. In this sense, bilateral relations are more actor-driven.

Defense and security

We don’t expect Turkey to leave NATO in the foreseeable future. The Shangai Cooperation Organization (SCO) does not have the structure that can provide an alternative to NATO. But if there is to become a security-defense split, our network attributes this to a refusal of Western allies to understand Turkey and its concerns.

There are several issues that complicate defense cooperation between Russia and Turkey: Turkey’s NATO membership, the Ukraine crisis, and the Crimea annexation. Also note that one of the most interesting outcomes of the improvement in Turkish-Russian relations has been Turkey’s interest in the Russian air defense system S-400 (NATO reporting name: SA-21 Grumble).

First, one should remember that Turkey’s main argument about the S-400 procurement was centered on the West’s reluctance in military cooperation, especially when it comes to defensive strategic weapons. Open-source pieces of evidence suggest that the Russians offered no co-production, offsets, or tech-transfer for the S-400 sale, whereas certain levels of offset prospects are on the table with the Patriot offer. If Washington and Ankara could negotiate good offset options for Turkey’s burgeoning defense industry, and if the problems related to the F-35 deliveries could be ironed-out, the Turkish administration could find a face-saving way out of the S-400 deal without upsetting the critical bilateral ties with Russia.

The military cooperation with Russia could focus on short- to medium-range mobile air defense systems that combine anti-aircraft artillery and surface-to-air missiles. The Russian defense industry is also very capable of producing this class of weaponry. Acquiring such a capability would provide ground troops with reliable protection, especially when conducting cross-border incursions. Such a capacity, for example, could have prevented the Baath regime’s 24 November 2016 attack on the Turkish troops and the incidents that claimed four lives during Operation Euphrates Shield.

Overall, “ideal world” scenarios seem far from the present reality in the Turkey – Russia – US strategic weapons triangle. Most likely by some point in the 2020s, we will not see the Turkish Air Force flying ALIS-connected F-35s, deploying the Patriot PAC-3 MSE systems against ballistic missile threats, and fielding the S-400s for building A2/AD to be used as stand-alone systems at the same time. While all these arms are very capable and even inspiring to any military expert, they do not mix well due to political and technical reasons. Therefore, Ankara will eventually make a decision to go one direction or the other, depending on its foreign policy and defense modernization priorities. Forecasting this decision is not easy at the moment, yet we think that Ankara has recently been very eager to procure both Patriots and S400s.

Energy

Turkish-Russian relations have always been characterized by a complex set of geopolitical issues, in which energy “interdependence” has decreased the possibility of divergence between the two countries. Turkey is dependent on Russia to secure her energy needs. Today, Turkey buys about 55 percent of its natural gas and about 12 percent of its oil from Russia. This supply cannot (easily) be substituted from elsewhere. This fact, and the attendant risk of energy shortage, is such a major threat to Turkey that in many cases it hinders diplomatic maneuvers. For example, Ankara has remained passive with respect to Russia, opting not to protest too much at the Kremlin's assertive policies in the region and deciding to pursue its own political goals pragmatically. On the other side, Turkey is one of the countries that exports a significant percentage of Russian natural gas, second only to Germany. And in total Turkey is one of the foremost receivers of Russian energy export.

The Turkey-Russia-EU energy triangle is a relationship of interdependence and strategic compromise. Turkey has argued and will continue to argue vis-à-vis the West for their position (including relations with Russia) and relevance in a strategic energy relationship with the EU.

Russia and Turkey have also created a Joint Fund to arrange their economic relations. The mutual fund is a crucial step for both bilateral relations and the closure of the current account deficit. For officials in Ankara, the aim of this fund is to strengthen local currencies against the dollar. Energy security has long been a vital priority in Ankara’s foreign policy making. Its relationship with regional producers has been shaped by Turkey’s goal to be a transit country linking Russia, the Middle East, and the Caspian Sea to Europe. The aim has been twofold: (1) to diversify energy suppliers in order to meet its own needs, and (2) to increase the country’s relevance as a transit zone.

The energy sphere, in particular, highlights several contradictions. Turkey’s national security relies on its ability to diversify its energy sources, yet Turkey has taken steps in recent years that have increased its reliance on Russian energy and technology.

Erdoğan’s decision to grant Rosatom the rights to build the Akkuyu nuclear power plant in southern Turkey is controversial and, according to a Brookings Institute article,[5] it would give Russia “control over a significant portion of Turkey’s electricity production.” In 2003, completion of the Blue Stream pipeline increased exports of Russian gas to Turkey, which now accounts for over 50 percent of Turkey’s overall gas resources. More recently, Erdoğan has signaled his approval for the Turkish Stream pipeline, which, as the paper highlights, will deliver 15.75 billion cubic meters of gas to Turkey and southeastern Europe by 2020. Interest in Turkish Stream could skyrocket if European Union countries decide to buy gas from Turkish Stream. The Russians are still planning to construct two pipes in the first phase. One of them will supply Turkey, and 16 billion cubic meters of gas from the other will be sold to Europe, Gokhan Yardim, the former CEO of BOTAS said in an interview with Al-Monitor.[6] However, if the EU does not turn out to be a good customer, gas from the second pipe could be sold to the Balkan states through bilateral deals. It is not possible to determine how lucrative the Turkish Stream will be as long as European demand remains unspecified. Next year, Turkish Stream will be entering the European arena as a producer and carrier when the TANAP, Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline, becomes operational.

In contrast to Turkey’s goals of diversification, both projects will aggravate Turkey’s dependence on Russian energy. Russia, by contrast, is interested in the stable export of hydrocarbons, the diversification of oil and gas transport routes linking it to external markets, and the export of nuclear technologies. As such, it has always regarded Turkey as one of its key energy partners in Europe.[7]

According to the Russian International Affairs Council,[8] energy cooperation between the two nations can be split into four major areas: (1) trade in energy products, primarily the flow of Russian natural gas to Turkey, which is the fastest developing area; (2) Russia’s oil and petroleum products that are shipped through the Turkish Straits, with a similar transit route for natural gas being a future possibility; (3) Russia’s foreign direct investment in the country’s energy industry, including the power generation sector, which has been increasing, specifically in nuclear energy, energy equipment supplies, and maintenance services; and (4) joint projects being carried out in the exploration and production of hydrocarbon resources in Russia and in third countries.

As long as Erdoğan “challenges” the Western world, particularly by challenging existing relationships with the US, NATO, and EU, Russia’s interest in being a “good friend” to Turkey will likely continue. But despite the efforts of “elites” to elevate the flourishing economic ties into a “strategic alliance,” in the long term such a move seems highly unlikely mainly due to the different (and, most of the time, conflicting) strategic cultures of the two countries.

The relationship could prove more difficult to balance against relationships with Turkey's Western allies and NATO membership as the conflict between Russia and the West intensifies. A close eye should be kept on developments in the Black Sea Region, a region that sometimes is overshadowed by the more explosive and rapidly developing issues in Syria. For Norway, this region is important with regards to Norway's NATO membership and multifaceted relations with European countries and the EU.

Black Sea Region

The security environment in the Black Sea region is rapidly changing. This region brings together Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, and a hinterland region, including the South Caucasus and Moldova. The situation in the Black Sea has been rather tense since Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014. The United States deployed some warships in the Black Sea after the Russian move. NATO refused to recognize the annexation.

The United States has been trying to counterbalance Russia’s growing military and logistics activities in the Black Sea by using NATO. In June 2016, NATO decided to boost its deterrence role in the Black Sea. This, after Erdoğan allegedly told the NATO general: “the Black Sea has almost become a Russian lake. If we don't act now, history will not forgive us.” NATO has become more and more important to Turkey in the Black Sea, irrespective of Turkey's rift with Western partners. Our interviewees told us that before 2014, Turkey could balance Russia in the Black Sea, but not any more, thanks to Russia’s military build-up in the region. For example, Russian cruise missiles cover the entire Black Sea and their air defense missiles range over 40-50%. Sevastopol (Russia's deep water port) has furthermore been a facilitator for Russian raids through the Bosporus into the Mediterranean and for quick supply runs to Russian forces in Syria. Turkey and other NATO members earlier favored a plan to anchor NATO institutionally in the Black Sea, with one example being a proposed naval task force that Romania, Turkey, and Bulgaria would form together with German, Italian, and US support. However, this initiative fell through. But again in 2017, NATO defense ministers endorsed an enhanced presence on the sea, in the air, and on land. Prior to 2014, NATO formulated their strategy with non-traditional security threats such as terrorism and trafficking in mind; now, NATO’s strategy focuses largely on Russian expansionism. According to Mustafa Aydin,[9] project member and Turkey's leading expert on Black Sea studies,

NATO’s current objective is to find a credible yet unthreatening strategy to deter Russia in its eastern and southern flanks. It is clear that further militarisation of the Black Sea will create an unstable environment that can bring Russia and NATO to the brink of a potential conflict. Though nobody benefits from such an escalation, we should remember that force projections in international relations, which are not countered properly, would eventually lead to further force projections and an eventual showdown.

The Black Sea brings together militarized confrontations, involving multiple actors and complex security and conflict dynamics, including those that stretch beyond the region to the Middle East and Europe. According to SIPRI,[10] protracted conflicts in the area have recently developed an external dimension in that they have become a source of political dispute between Russia and NATO, and furthermore, there is now increased military support for and military engagement with the different sides in the conflicts. With the Arab Spring, the boundaries between Middle Eastern and Black Sea security areas have blurred; some this development is due to the involvement of Russia and Turkey in the Syrian conflict.

Russian military involvement in Syria, Armenia, Georgia's breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and on the Crimean peninsula has fueled Turkish fears of encirclement.

Turkey, as mentioned earlier, has stayed away from being too vocal on Russia's annexation of Crimea and the Donbas conflict: for example, Turkey did not support Western sanctions, yet opposed the annexation of Crimea and supported the territories of the Tatar minority. This support increased during the Russia-Turkey crisis. However, the Crimea issue and the plight of the Tartars have little impact upon Turkish foreign policy. MHP is the only political party that has traditionally focused on Turkic communities abroad, and apart from within their base, typically has little domestic appeal in Turkey. Thus, although MHP is the “kingmaker” in the parliament, it is not likely that The Tartars is one issue for which they would try to exploit their leverage with AKP. Following Russian moves, Turkey also placed limits on shipping, but it seems like Turkish ships registered in other jurisdictions continue to break the ban.[11] Thus, although Turkey would prefer a stronger Ukraine that could act as an ally in the region, Turkey has for the most part stayed out of the conflict.

South Caucasus is another area where Russian and Turkish interests clash and where there is a potential for the two actors to be dragged into opposite sides of existing conflicts.

The Turkish tree-way partnership with Azerbaijan and Georgia has since the 1990s focused on energy, infrastructure, security, and defense. The near completed Southern Gas Corridor (expected to become operative in 2020), an initiative from the European Commission that is to link the Caspian Sea (and Middle Eastern) gas fields to EU countries, is one especially successful outcome of this partnership.

Since 2015 Ankara has both supported Georgia’s NATO application and signed defense agreements with Ukraine. But as partner in this region, Azerbaijan is the most important one. And on this issue the public supports the government. A study from Kadir Has University (2019)[12] showed that most of the respondents—63,6 %—regarded Azerbaijan as Turkey’s ally

and/or friend. Next on the list was Northern Cyprus with 59,1 %. Given that Turkey is a nation that wishes to become an energy hub, exerting influence over Azerbaijan's oil production and export as well as working together on different energy projects such as the Southern Gas Corridor are both important.

In 2010, Turkey and Azerbaijan signed an agreement on Strategic Partnership and Mutual Support that includes obligations to assist each other using “all possibilities” in the event of military attack on either by a third country.[13]

Turkey knows that Russia is the dominant actor in the Black Sea region, and consequently Turkey maneuvers to achieve its interests in the region without making too much noise.

The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan is a particular challenge to the Turkey-Russian relationship. Russia supports Armenia through defense cooperation and through the Collective Security Treaty Organization. Russia, however, also sells weapons to Azerbaijan and is moving closer to Baku for example through the Azerbaijan-Russia-Iran initiative.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is one that does not often hit the international headlines. It is a low intensity conflict that has had regular flare-ups since the ceasefire agreement in 1994, the most dangerous being the flare-up in April 2016. Exchanges of angry words between Turkey and Russia initiated by the flare-up in Nagorno-Karabakh illustrate the commitments on both sides. However, the rhetoric did not fuel further escalations: Turkey at the time was preoccupied with domestic and other regional problems, and Russia was able to renew the ceasefire between Azerbaijan and Armenia within days. While violence was relatively quickly controlled in 2016, it is important to remember that both Azerbaijan and Armenia are among the ten most militarized countries in the world. Azerbaijan has increased its military capability twenty-fold since 2004, and Armenia gets regularly military support from Russia. The conflict has the potential to draw in Russia and Turkey, but also other international and regional actors such as Iran and the US. The worst-case scenario is one where the conflict escalates out of control and melts together with conflicts in the Middle East, especially the one in Syria. Nagorno-Karabakh also has security and political implications for Europe. OSCE is involved as a facilitator and leads the Minsk group that, together with France, Russia, and the US, seeks to broker a peaceful resolution of the conflict.

With the relations improved between Russia and Turkey, they could use their rapprochement to, if not solve the conflict in the Black Sea Region, at least diffuse violent outbreaks as ICG has argued.[14] However, according to Gürcan,[15] a cooperative attitude in the Black Sea between Turkey and Russia will not be easy to achieve as long as it does not include other coastal countries.

Concluding

Turkey will continue to reaffirm its relations with Russia. Erdoğan also has the backing of the Turkish people on this front. In a recent Kadir Has study[16] on foreign policy attitudes, 4,1%[17] considered Russia to be a friend of Turkey and placed Russia number two on the list of friendly countries (59,0% answered Azerbaijan and 22% answered that Turkey has no friends). 46,5% of the respondents, compared to 28,4 % in 2017, defined Russian-Turkish relations as cooperative. The top three ways in which Turkey was seen as benefiting from the relationship were energy cooperation, cooperation in tourism, and trade/economic cooperation. Top three sources of enmity were Russia's support to PYD/YPG forces in Syria, the historical rivalry and enmity between the two countries, and Turkey’s shooting down a Russian aircraft.

Turkey's dependence on Russia when it comes to energy and to reaching its objectives in Syria are the fundamental drivers when it comes to keeping the relationship on track. Ankara and Moscow will have to control negative impacts of external factors upon its relationship. The parties work on an ad hoc basis, rather than seeking to build new institutional mechanisms. It is also hard to ignore the importance of backdoor diplomacy, but the pace of bilateral steps taken for turning back to pre-crisis level cooperation seems to be falling behind the prevailing rhetoric.

There is little evidence to suggest that Turkey will opt to enter an alliance with Russia at the cost of its NATO membership. Turkey could use its relations with Russia to diffuse tension between East and West as well as to further its strategy to balance its relationship with Russia and with Western partners so as to (try to) maximize its interests. Andrey Kortunov, Director General of the Russian International Affairs Council asks, ”Why doesn’t Ankara take an initiative in promoting more confidence-building measures between Russia and NATO in the Black Sea?” And then he continues, “Thinking strategically, one can even imagine a more important role for Turkey as a country that might be best suited to facilitate a renewal of the currently nearly dormant NATO-Russian Council.”[18] Our assessment is that in theory, Turkey could aspire to such a role, but at the moment we do not foresee such a move by Ankara due to: (1) the Presidency’s anti-Western rhetoric and, Turkey’s estrangement from certain NATO members; (2) its lack of institutionalized connection to Russia; (3) the implementation of the presidential system that makes foreign policy strategic planning difficult, and (4) the weight of domestic and other foreign policy issues.

Turkey's relations with the US

By the end of the 2nd World War, Turkey chose to side with the Western alliance and moved close to the new superpower, the United States. When Stalin in 1946 opted for Turkish territory, the Turkish leadership’s alliance-forming initiatives with the US picked up speed. The threat posed by Russia aligned Turkey completely with the US, who in return granted Turkey security guarantees. The relationship with Washington became a bulwark of Turkish foreign policy and a crucial insurance policy against the Soviet Union. In 1952 Turkey became full member of NATO, thereby cementing Turkey's Cold War alliance with the US. During this period there were intermittent problems in the relationship, such as the 1974 Cyprus War. Still, the Turkish leadership placed trust in its close alliance with the United States to guarantee its security throughout the Cold War. According to Cagaptay,[19] while Erdoğan, like his predecessors, has sought to reclaim great power status for Turkey, he has departed from previous strategy in one significant way:

Erdoğan has rejected the idea of tying Turkey to great powers while working toward his goal. He has instead moved to cast Turkey as an autarchic power wielding influence over its neighbors, occasionally rejecting traditional Western partners, and seeking new relationships with Russia, Iran, and China.

From our contacts we learned that with the election of Trump and his apparent fascination with authoritarian leaders, some government officials hoped for an improvement in the relationship, after a rather cold period at during the end of the Obama period. This has proven at times to be the case: Erdoğan and Trump seem to get along on a personal level. Nevertheless, the relationship between the two countries has had some serious troubles in recent times.

The Andrew Brunson Case.

Andrew Brunson, a pastor who had for about twenty years been living in Turkey and who worked as a pastor of the Izmir Resurrection Church, in October 2016 was arrested and charged with espionage and links to the Gülen network and the PKK. In August 2018, after rounds of unfruitful diplomacy, the US Treasury Department imposed sanctions on two Turkish Ministers, and Trump announced sanctions on Turkish aluminum and steel imports. This move sent the Turkish Lira in a tailspin, and finally in October 2018, Brunson was released and sent back to the US and sanctions partly lifted.

Fethulla Gülen

Shortly after the botched coup attempt of 15 July 2016, the Turkish government stated that Fethullah Gülen and/or his movement had organized the coup attempt. Fethullah Gülen, an earlier strategic partner of the AKP, has lived in the US since 1999. After the failed coup, the Turkish government has made Gülen's extradition one of the central points of its foreign policy towards the US. The United States has demurred, claiming that Turkey has not presented sufficient evidence against Gülen to justify extradition proceedings. Trump has promised to look into the matter as White House spokeswoman Sarah Huckabee Sanders stated on 18 December 2018[20], however Turkish diplomats have claimed that Trump promised Erdoğan, at the G20 summit in Argentina, to extradite Gülen to Turkey. Early in January a special team from FBI came to Ankara on a special visit arranged by the Trump administration after the phone call with Erdoğan on 14 December 20118. The team visited prisons and interviewed the high profile figures who allegedly masterminded and commanded the coup attempt, such as Kemal Batmaz and some top generals. The team also visited Turkey's Ministry of Justice and was given some reportedly solid evidence to Gülen's involvement in the failed coup. Our perception is that the Trump administration is looking for solid evidence, if any, of Gülen's direct involvement to increase pressure on the Gülenist network in the US and possibly pressure the US legal system to extradite Gülen. As Sinan Ülgen has argued,[21] ”What Trump could do is press the US Justice Department to review and work more collaboratively with the Turkish authorities to build a case. They could work with their Turkish counterparts to prepare a file that would be sufficient for the US courts.”

Problems with the US Congress.

When Erdoğan's security detail beat up protesters in Washington, DC in May 2017, it caused heavy criticism from the Congress and prompted Senator John McCain to state that the US should expel the Turkish Ambassador. The Michael Flynn case, which involved an allegation that Mr. Flynn had lobbied the Congress for the extradition of Gülen and allegedly had a plan to “kidnap” Gülen and deliver him to Turkish authorities,[22] also did not sit well with members of Congress. Connected with the release of Mr. Brunson, Ankara tried to secure the transfer of a Turkish banker, Mehmet Hakan Atilla.[23] The deal was simple, but it failed. US sources suggested that Turkey added a demand at the last minute regarding Halkbank (a Turkish state-controlled bank) – asking for leniency in paying a US Treasury fine on the bank and for there to be no new indictment. Meanwhile, Turkish media reported that it fell through due to new investigations by the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). In 2012, Atilla was, according to the charge, involved in a scheme to help Iran spend oil and gas revenues abroad using fraudulent gold and food transactions through Halkbank, violating US sanctions. The delicate diplomatic twist to this case involves the wealthy Turkish-Iranian gold trader Reza Zarrab. He testified during the trial in New York that he bribed Turkish officials and that Erdoğan personally signed off on parts of the scheme while serving as Turkey’s prime minister. Atilla was sentenced to thirty-two months in prison. In July 2018, Legislation was introduced in the Senate that seeks to restrict loans from international financial institutions to Turkey until the Turkish government stops its “unjust” detention of American citizens.[24] This bill suggests directing the World Bank and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to oppose future loans to Turkey, except for humanitarian purposes. The EBRD invested 1.5 billion Euros in Turkey in 2017.

S-400 (SA-21 Grumble)

The US Congress seeks to prevent Turkey from purchasing F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Jets should Ankara decide to go for the S400 (a long range surface-to-air missile systems) deal with Russia. Forecasting this decision is not easy at the moment, yet we think that Ankara has been very eager to procure both Patriots and S400s. The real question is whether or not this endeavor would be tolerable in Washington. The US Congress, the Pentagon, and many circles in NATO have been very disturbed by Ankara’s decision to procure these two systems together. Many factors, ranging from the US support to the YPG / PYD in Syria to Russia’s stance in Idlib, could affect the Turkish administration’s roadmap on this front. One thing is certain, though: Turkey is a powerful G-20 and NATO member with a game-changing regional posture. Whatever the decision between the Patriot and the S-400 is, it will have broad geopolitical ramifications.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)

Trump's disregard for the Iran-deal (JCPOA) is another area where Turkey and the US don't see eye to eye. Erdoğan wants the deal to stay in place, in line with the wishes of the other partners in this deal and of several others. Turkey has many interests in trading with Iran, especially in Iranian oil and gas. On 25 July 2018, Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu rejected US sanctions against Iran: “We have no obligation to support the unilateral sanctions of one country against another country, especially when we think they are inappropriate,” he said, adding, “If we do not buy oil and gas from Iran, where should we provide our needs from?”[25] Turkey is on the list of countries that is temporarily exempted from secondary sanctions imposed by the US. However, we expect the JCPOA to be a source of disagreement and tension in the future.

Jerusalem Peace Plan

Just as we are about to conclude this report, the news broke that Jared Kushner (US senior advisor in charge of brokering peace in Israeli–Palestinian conflict and son-in-law of President Trump) met with Erdoğan and Albayrak (Minister of Finance and Treasury and son-in-law of President Erdoğan) at the Presidential Palace in Ankara. One of our contacts in Ankara informed us that the following topics were on the table at that meeting:

- Ankara’s support for Trump’s Jerusalem peace plan, as well as Kushner’s asking for Ankara’s support to influence Palestinians.

- Iran and US’s economic sanctions: Kushner warned Ankara that, in the post-ISIS setting, both in Iraq and Syria, Iran is the emerging enemy and the Trump will not tolerate Ankara’s attempts to break US-imposed economic sanctions against Iran.

- Ways to boost economic ties between Turkey and the US, and Ankara’s attempts to boost American investments in Turkey (we think this is why Albayrak attended the meeting[26])

- Potential removal of Turkey from the F-35 consortium and the possible second order impact on legacy licensing, both of which hit right at the post-1980 framing of the bilateral relationship. We perceive this problem to be the most explosive issue in the bilateral ties between Turkey and the US in the coming months. We expect that Erdoğan asked for Kushner’s help to defend Turkey in Washington, DC against the Congress and US’s security bureaucracy.

- Halkbank/Zerrab case and Trump’s backing for the possible return of Hakan Atilla, the deputy president of Halkbank currently imprisoned in the US.

We expect that if there were to be presented a new peace plan for the Israel – Palestine conflict, that this will result in substantial disagreement between the two countries. President Erdoğan will advocate for the Palestinian case in the international, regional and domestic arena if he sees/perceives that the plan fails to accommodate the Palestinian's claims/rights. A counter-argument to this involves the mediation aspirations of The Turkish government. If there were a role for Turkey to assume in this peace process, this prospect would put a temporarily lid on criticism coming out of Ankara.

Syria: Disengagement and Pullout

First, Turkey perceived that is was left alone in advocating that the Assad regime had to step down after the US disengagement from Syria (apart from ousting/fighting ISIS). Now Turkey is “forced” to work with Iran and Russia. Turkey perceives that it does not have the option to leave Syria militarily or otherwise, since the developments there are closely linked to Turkey's security. The latest cooperative plan of Iran, Russia, and Turkey has come via the Astana process (see image below).

Second, the US has demonstrated a lack of sensitivity toward an ally's national security concerns by partnering with YPG (against ISIS) in Syria. YPG, which has (strong) connections with the PKK, has been designated a terrorist group by both Turkey and the US. Washington and Ankara have strongly disagreed about whether YPG is connected to PKK, Interestingly, in their yearly threat assessment the US intelligence community confirms this connection.[27]

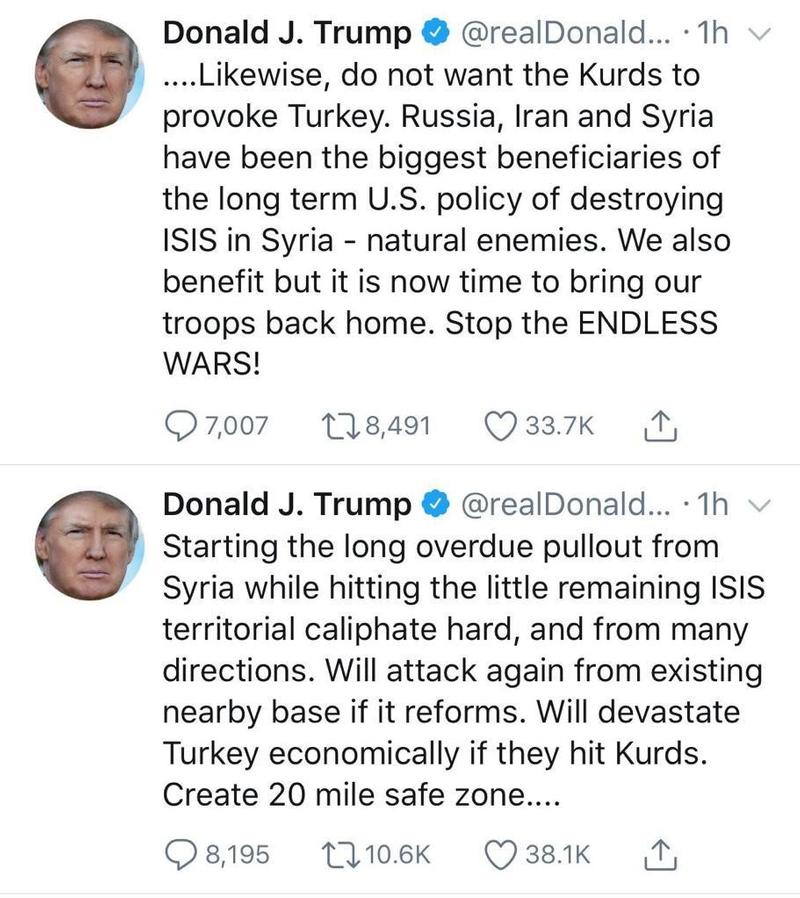

Third, on 16 January 2019, President Trump announced that the US would withdraw from Syria through this Twitter:

President Erdoğan responded through an Op-Ed in New York Times:[28]

Erdoğan gives Trump right in his decision to depart Syria, but that it should be done so as to to meet “interests of US, international community and Syrians”

Erdoğan argues: (1) Turkey is the only actor that can lay claim to “American Succession” in Syria, because it’s a loyal, combat-capable NATO member safeguarding its southern borders from ISIS terrorists. (2) Turkey is the only one who simultaneously works both with the US and Russia; on both Geneva and Astana processes – the US needs Turkey to understand Moscow’s moves. (3) Turkey is also a victim of ISIS, Erdoğan is their personal sworn enemy, and thus the policy to finish them has a deep personal dimension to Ankara – and employing this argument, he dismissed arguments of those criticizing Ankara for collaboration with terrorists. Erdoğan also made three arguments disparaging the US: (1) unlike the US, Turkey knows how to operate carefully (points to destruction of Raqqa, Mosul, and preservation of Al Bab); (2) unlike the US, Turkey has a “comprehensive strategy;” and (3) the US didn't learn lessons from the Iraqi campaign, but Turkey did. Here he addresses nationalists at home and seeks to make align with skeptics of the US government. Finally, Erdoğan offered reassurance: Turkey is not what “Turkey-haters” imagine. Turkey hosted both Christians and Yezidis when they had to flee from ISIS. Turkey is no enemy to Kurds. Those who joined YPG are just prodigal kids who will be accommodated. And he reiterated that YPG is a branch of PKK, which is recognized as a terrorist organization by US as well.

Anti-US/West sentiments

Amongst the nationalists and in the press close to Erdoğan, the US pullout was seen as a result of Turkey’s policies in Syria, as Yeni Safak illustrates:[29]

Trump's decision to withdraw from Syria, even if only seemingly, is a result of Turkey's determined attitude since Operation Euphrates Shield; it is the US faltering and taking a step back.” But also with skepticism: ”if US troops withdraw from Syria, even partially, it is going to continue its plans with organizations, terrorists, hypocritical evil forces and countries that are its puppets.

Anti-American sentiment rose in Turkey, with the Turkish president blaming Washington for the collapse of Turkey’s currency. Consider the following example of his fierce rhetoric from August 2018: ”An attack on our economy is no different from a direct strike against our flag and call to prayer. The aim is no different. It is to bring Turkey and the Turkish people to their knees.”[30]

Ibrahim Kalin offered a typical follow up on this line of argument when, in a written statement to Reuters[31] Kalin responded to John R. Bolton, National Security Advisor of the United States, commenting on the sanctions. There Kalin claimed: “His statement is proof that the Trump administration is targeting a NATO ally as part of an economic war”

One of the more explicit examples of anti-American rhetoric in the Turkish press came from Ibrahim Karagul, editor in chief of the pro-government Yeni Safak:[32]

What’s more, the US is now the closest, greatest and most open threat for Turkey. It is an enemy country. It is a serious threat to our country’s existence, its unity, integrity, present and the future. It is carrying out an open attack, and an undeclared war against Turkey.

Ankara seems to have no appetite for keeping pro-Western sentiment strong throughout Turkey. The “New Turkey” and its motto “Yerli ve Milli Turkiye” (Local and National Turkey) constitute the foundational theme of Turkey’s new executive presidential system, which revolves solely around President Erdoğan’s persona. However, the heart of the issue is the multilayered relationship between the AKPs new self-image project, neo-Ottomanism, and the international developments shaping it. Just after the 15 July 2016 military uprising, the AKP, leaning on existential anxiety, retreated to survival mode, making a U-turn from the inclusive internationalist discourse it began peddling in 2002 and turning toward the “yerli ve milli” route of ultra-nationalists. Unfortunately, the perceived other—or the enemy—of this new national identity and collective memory construction process has become the collective image of the West, thus diluting pro-Western sentiment among Turkish citizens.

International image theory endorses a functional approach in suggesting that images, such as the image of another country an enemy, serve to justify behavioral tendencies toward other nations, as well as maintain a positive and moral image of one’s own nation.[33] Specifically, the enemy image has the power to unite people against a mutual enemy. Erdoğan has over the years consistently used both outside and inside enemy-images to energize politics for domestic political consumption. After consuming the energy of all domestic rivals, his new enemy is pro-Western sentiment in Turkey. To weed out the West and its ideas, President Erdoğan’s “other-ification” of NATO, for example, has come to the fore of his political agenda. Domestically, he is merging the established Kemalist-leftist discourse and the conservative-nationalist discourse controlling his powerbase so as to create a “nationalist bloc” around his persona as Turkey speedily heads toward local elections in March 2019. According to image theory, for people who highly identify with one's country (e.g., nationalists), the intensity of emotional responses to threats or opportunities will be strong.[34] Some analysts have pointed to this wave of nationalist sentiments as proof that the Eurasianist ideology has gained popularity in the population and in Ankara. The Eurasianist advocates argue that the international geo-economic and geo-strategic center is shifting to the East and, as a consequence, Turkey is becoming a new strategic geographical center. Second, they argue that global security issues are not something that the West is capable of resolving. They warn further that Turkey's two-century Westernization process should undergo a critical review so as to not end up with a new Treaty of Sevres (1920). The EU and NATO are currently struggling with structural crisis, and globalization is deepening inequalities in the world at the benefit of the West. Turkey's position is clearly becoming one situated within the clash between global capitalism and national state structures. And finally, since NATO, the US, and Europe are not supporting Turkey’s security concerns, Ankara needs to draw up its own strategic vision, relying on its own power. In political circles, the marginal Vatan Party[35] led by Doğu Perinçek is perhaps the best representation of this ideology. Turkish think tanks such as the Anka Institute, 21st Century Turkey Institute, Center for Middle Eastern Strategic Studies, Turkish Asian Center for Strategic Studies, and the Institute of Strategic Thinking have increasingly come to articulate the idea that the West is broken and that it is time for Turkey to turn towards the East. We should note, however, that this rising trend is more apparent in terms of foreign policy, defense, and security rather than economic and social life.[36]

So does this mean that Turkey will take a Eurasian turn at the expense of relations with the US, EU, NATO, and other Western nations? We think such a move is not very likely, as described when it comes to security and defense above (p. 8,17). Another significant argument against this position is the fact that Turkish Islamists, although they may reject the Western culture, embrace the capitalist economic order, which they see as necessary for Turkey's exports and capital accumulation. Also, remember that the Islamist-conservative movement grew up with and benefited from Turkey’s economic liberalization and its deepening integration with the capitalist world economy.

Public perceptions of the US

In a recent survey of social and political trends in Turkey (2019) conducted by Kadir Has University and led by Mustafa Aydin[37], the US is ranked as the greatest threat to Turkey (in response to the question: Do you think the following countries pose a threat to Turkey?). Before commenting on this result, it is worth noticing that the inclusion of respondents along political party affiliation in this study provide a quite accurate mirror of the actual election results from 2018 general election.[38] The perception of the US as the number one threat to Turkey, in the context of foreign relations, has been consistent throughout the past three years. However, during the last year there was a significant rise: from 64,3% of the surveyed in 2017 to 81,9 % of the surveyed in 2018 (2016: 60,4 %).

In another Kadir Has survey (summer 2018)[39], specifically focusing on foreign policy, 79,3 % of the respondents reported that they found that the relationship between the US and Turkey had problems. The top three problematic issues were listed as (1) Counterterrorism, (2) Extradition of Fethullah Gülen, and (3) US support of PYD. When it comes to the most important areas of cooperation between Turkey and the US, the respondents listed Economic cooperation, Military Cooperation and Counterterrorism. When the respondents were asked to define the US in its relations with Turkey, 84, 2% used negative characteristics to describe the relation, while 15,5 % used positive terms: Unreliable country (38,9%), Imperialist country (29,1 %), Hostile country (16,2%), Strategic partner (11,4%), Ally (3,0%), and Friendly country (1,1%). While reading these results as an indicator of how a cross-section of the population perceive the relations with the US, it is also important to notice that 15% of the respondents thought that Turkey should act alone on the international arena. No country apart from Azerbaijan (38,9%), Turkic republics (31,8%) and Muslim countries[40] (23,4%) got over 15% (Turkey should act alone).

All in all, these results (and similar results for other Western allies) suggest that political leaders like President Erdoğan, who stir up tensions with the West, highlight connections with the Muslim world, and promote military operations outside Turkey, are likely to receive public support. However, given the importance of Western countries to the Turkish economy and security, to fully act on the apparent preferences of the people would likely prove too costly. Although political leaders and the public are likely to maintain their anti-Western stance for ideological reasons, we expect that the leadership will continue to manage its economy and security predominantly via its relations with the West.

Changing perceptions in the US?

There are signs emerging in the US that foreign policy political elites also are re-evaluating the partnership with Turkey. It is argued that Turkey and the US do not share interests or values and that their ties are characterized by ambivalence and mistrust. When it comes to economic relations, according to Khush Choksy (senior vice president for Middle East and Turkey Affairs at the US Chamber of Commerce),[41] significant challenges exist and are preventing the US-Turkey commercial relationship from reaching its full potential. Turkey maintains a spot in the G20 as the 17th largest economy in the world, but the $20 billion in trade volume between the US and Turkey is lower than that of US trade with smaller economies, such as Belgium, Colombia, and the Philippines. High tariffs and market access barriers on both sides of the Atlantic limit the free-flow of goods and services. Steven Cook argues in his latest Council of Foreign Relations Report that we are witnessing the gradual but steady demise of a relationship: Turkey may be an ally in the formal sense, but it is no partner.[42]

Concluding

Perceptions in international relations are often shaped in terms of mirror images: while considering one’s own action good, moral, and just, the enemy is automatically found to be evil, immoral, and unjust. This might be what is happening in the Turkish – US relations, where the two actors seems to mirror one another in important areas in undermining the idea that the United States and Turkey share interests and goals. US and Turkish officials believe their counterparts support terrorists, abet the exercise of Russian power, and pursue policies that destabilize the Middle East.

Turkey's relations with the EU

“The EU will never allow Turkey inside because of its religion and big population”, Erdoğan recently stated.[43] But he should have added that Turkey’s departure from fundamental EU standards makes an entry into the Union impossible. The most recent breaking point of the relationship can be attributed to the failed coup d’état in Turkey in 2016. The perception advanced by Ankara is that the EU did not and still does not understand the seriousness of the failed coup to the country’s security and democracy, and that the EU applied double standards in its condemnation of post-coup actions taken by the government. Amongst the people there is a feeling of abandonment—that European countries don’t really care about Turkey and the trauma that people experienced the night of the coup and in the following days. They point to the unity and compassion that was extended to France, both from world leaders and people, in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo (2015) attack. Although not similar events, the psychology of experiencing a national trauma and receiving support and empathy versus experiencing a national trauma and receiving only conditional support or indifference helps create negative images of other countries as well as shape the self-images Turks hold of their own country and fellow countrymen[44].[45]

Following the failed coup the Turkey - EU relations fell into its most difficult period since the accession negotiations were opened for Turkey in 2005, and perhaps even in its history.

The most difficult issue of divergence was the degree to which the coup attempt and the coup-plotters posed a threat to the Turkish political system. Ankara claimed that Turkey confronted an existential threat that warranted extensive actions that the government undertook by declaring state of emergency and implementing an unprecedented crack-down on people who could have had something to do with the coup or the Gülen-movement in general (and many others in opposition to the regime). Turkish commentators throughout the Turkish media-spectrum noted the lack of understanding EU officials demonstrated to the dangers Gülenists posed. When the European Parliament voted to suspend negotiations in November 2016 and on 6 July 2017,[46] this was seen as further proof that the EU was clueless about political struggles in Turkey.

Within the EU member states, the Turkish question can be seen as a fault line, where Central and Eastern European, Baltic, and Mediterranean member states are more in favor of keeping the accession framework in place, whereas Germany from 2017 became highly vocal about its opposition to Turkey’s EU accession. Angela Merkel went as far as stating, “There cannot be a Turkish accession to the EU.”[47] By that time the relations between Turkey and Germany had already hit an absolute low point, with Erdoğan calling the German position towards Turkey's accession comparable to “Nazi Germany” in the context of Turkey’s accusing Germany of harboring terrorists behind the coup attempt and Germany’s criticizing Turkey for arresting German nationals without due process.[48]

The Turkish people have over the years varied in how they view Turkish potential EU membership. After the coup attempt in 2016, the percentage of the respondents in favor of membership hit an all time low since Kadir Has and Prof. Aydin had started the surveys in 2012, with only 45,7 % favoring[49]. Compared to a similar study[50] surveying foreign policy perceptions conducted before the coup attempt showing that 61, 8 % of the surveyed were favorable, we can assume the response from the EU on the coup attempt and the following deterioration in relations along with the government's rhetoric had an clear effect on public opinion. The latest survey (2018)[51] on foreign policy perception show that 55,1% is in favor of a membership. 50,8% agree that being an EU member would be beneficial to Turkey and of those 73,4 % think economic standards would improve, 46,1 % that democracy would improve, and 37,8 % that human rights would improve. The two latter results serve as an indicator that the Turkish people still assess that the EU would have an ability to convey normative and value-based change in Turkey. However, in a more pessimistic assessment 71,7 % think that Turkey will never become a full member. 64,4% of the respondents believe that Turkey's membership is being blocked and 58,7% (of those 64,4%) attributes this to religious and identity differences.

Recent developments in Turkish –EU relations have been rather negative on the part of Turkey. On 19 February 2019 the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament told the European Commission and EU member states to freeze accession talks with Ankara over amongst other issues:[52] its human rights record, partisan judiciary, and the Cyprus case. There, the Committee stated:

Taking all of the above into account[53], recommends that the Commission and the Council of the European Union, in accordance with the Negotiating Framework, formally suspend the accession negotiations with Turkey; remains, however, committed to democratic and political dialogue with Turkey (…).[54]

As only the EU heads of state have the power to freeze or end Turkey’s accession process and given that such a decision would have to be unanimous, this decision of the Foreign Affairs Committee is just a recommendation, but it is an indication of current attitudes within the Union. In the same document the committee stresses that:

(…) the modernisation of the Customs Union would further strengthen the already strong ties between Turkey and the EU and would keep Turkey economically anchored to the EU; believes, therefore, that a door should be left open for the modernisation and upgrade of the 1995 Customs Union between the EU and Turkey (…).

and furthermore:

Notes the importance for both the EU and its Member States and Turkey of maintaining close dialogue and cooperation on foreign policy and security issues; encourages cooperation and further alignment on foreign policy, defence and security issues, including counter-terrorism cooperation (…).

The Foreign Affairs Committee is also highlighting the importance of the “EU-Turkey joint action plan”[55] by asking the Council of the European Union to recall “the important role played by Turkey in responding to the migration crisis resulting from the war in Syria (…)”. The three highlighted area-recommendations for further cooperation, in case of suspension of the accession talks, displays the weight that the EU puts on strong ties with Turkey on the commercial, economic, military, counterterrorism, and humanitarian fronts.

What kind of partnership?

The European Union is Turkey’s irreplaceable partner for exports, service provision, and foreign direct investment. With regard to foreign direct investment, of which Turkey is in dire need given its economic situation, 63, 4 % came from the EU in the period from January to April (2018), with Austria, the Netherlands, and the U.K. being the top three European sources.[56] Turkey says joining the affluent bloc remains one of its strategic goals. As stated by the Turkish Foreign Minister: “In Europe we are at home, just like the EU countries are”, and furthermore: “Both the NATO alliance and the EU membership will continue to be our key direction.”[57] And in light of recent developments it is worth remembering that in the Turkish diplomatic context, tensions with Washington regularly lead Ankara to look to Europe instead. Past difficulties with the European Union appear on hold and shared anger directed at US President Donald Trump is providing a helpful common ground. Turkey has sought to repair ties over the past year, especially commercial links with its biggest trading partner during a harsh economic downturn. However, given Turkey’s current differences with Europe, Ankara may have to pay a high diplomatic price for any reduction in diplomatic tensions. Turkey will have to demonstrate some improvements in its governance system if it wants to see progress in even limited areas such as the Customs Union and visas.[58] Through our network we have also been informed that Turkey-EU ties have recently been warming and Ankara seems to have no appetite for scapegoating European countries, even though it is “election season” in Turkey. Furthermore, somewhat to our surprise, many in Ankara believe that, if Erdoğan were to get what he wanted, he would over time initiate a big normalization process with the EU, leading to the reemergence of pro-EU sentiment in Turkey.

Consequently, the vital interests of the EU and Turkey are in many areas intertwined, and even if there is an termination of the accession talks, the two parties must find ways to move forward with the relationship. There has been talk that Turkey could acquire a “privileged partnership” that the German Chancellor Angela Merkel contemplated in 2005[59] and which the Turkish government vehemently opposed.[60] Turkey already has a high degree of functional cooperation with the EU, which takes multiple forms in terms of economic, political, judicial and internal affairs, energy, and environmental cooperation.[61] According to Meltem Müftüler-Baç Professor at Sabancı University in Istanbul:[62]

External differentiated integration for a non-EU member such as Turkey might involve temporal alignment to EU policies and territorial inclusions—such as security cooperation, its Customs Union or visa rules for third parties and policy opt-ins such as the adoption of EU regulations in electricity, telecommunications, and education. These multiple layers of integration between Turkey and the EU keep their functional cooperation on track.

From the Kadir Has survey on foreign policy perceptions[63] we see that the idea, although not popular, has attracted more support over time. Answering the question Should Turkey and the EU establish a model of relationship other than membership? 30,4% of the respondents answered yes in 2017 and 32,1% in 2018. Comparably, the idea of a “privileged partnership” received positive reaction of 22.8% in 2015, and of 23.8% in 2016. Some analysts also seem to conclude that President Erdoğan seems to have warmed up to the idea when he recently stressed, in the context of EU membership, that: “We should obviously have Plan B, Plan C,” although it is not fully clear what he meant by this statement.[64]

Concluding

The Brexit process (should it be concluded) indicates that different models of integration are possible for the countries that either is unwilling or unfit for EU membership, as is the EEA of which Norway is a member state. On the side of the European Union, they know that for the next five years they would have to deal with President Erdoğan. If they decide to end Turkey’s accession process talks, reinstating them would require unanimity, which would be almost impossible to attain again. This makes suspension a highly risky path to pursue. So the safe thing to do might be to treat Turkey with a privileged partner status, if not formally stated, at least in practice. The project members do not in any case foresee a break in relations moving forward and developments should be read through the high level of interdependent interests between the two actors.

Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean forms a geostrategic fault line between Europe and the Middle East. Wars, genocidal acts, nationalist movements, and upheavals have scarred the region over centuries and have presented the international system with some of its most vexing strategic challenges.

Today, the Eastern Mediterranean Sea is also a very busy place, and tensions abound among coastal neighbors there. In addition, the involvement of several “outside” powers such as Russia, Iran, China, and the US is not making the situation any easier.

The area has been and still is burdened with: State fragmentation as for example in Libya and Syria, where the situations are made worse by non-state actors like ISIS. Migration from conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, creating one of the largest refugee crises since World War II and resulting in nationalist and xenophobic political sentiment that has strengthened ultranationalist political parties. Geostrategic rivalry between the US-led Western Security block and Russia, particularly, over the control of sea routes and air space over the Eastern Mediterranean. Economic crises as in Greece, Cyprus, Lebanon, and Egypt; countries that have faced destabilizing economic crises in the last decade that have created deep political and strategic vulnerabilities, and Turkey could possibly face similar challenges. Energy prospects as for example gas discoveries outside Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt that have boosted economic prospects in the region and drawn the attention of external actors.

In the sections following we will take a look at the East Mediterranean from the viewpoint of Turkey, focusing on energy and security.

With the discovery of natural gas and the prospects of further discoveries, costal governments are declaring exclusive economic zones (EEZs), but the problem is that those zones overlap. States are granting duplicate licenses for natural gas exploration and drilling. Mammoth energy corporations and coastal states are signing hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of hydrocarbon agreements that cover contested research zones, the legal status of which remains fuzzy. Frequent maritime safety broadcasts inform citizens of endless military exercises.[65]

The energy issue has been seen as one factor that could aid the unification of Cyprus, as the two parts of that nation realized the potential economic benefits to a unified island. But the energy issue has become a negative factor, problemazing the negotiations and leading to intense conflict between Turkey and the Greek Cypriots. Turkey does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus (RoC) and argues that the Greek Cypriots cannot conclude agreements, such as the delineation of an EEZ, or issue licenses for the exploration of natural resources without the Turkish Cypriots’ consent or participation. The Greek Cypriots, however, point to past ”understandings” reached under negotiations that any revenues from resources would be shared with all Cypriots. The admission of RoC to the EU in 2004 turned this bilateral crisis into a more complex one, operating at multiple levels of analysis. The United States and the EU have long supported the RoC's right to explore for energy in its EEZ, but both have expressed their hope that the economic benefits of such exploration could eventually redound to everyone on the island. In 2004, after the admission, the European Union had declared the Greek Cypriots the sole entity representing the island of Cyprus. Feeling their strength following the EU decision, the Greek Cypriots claimed the right to natural resources exploration in the EEZ around Cyprus. Turkey, however, has been insisting that the Greek Cypriot administration in Nicosia cannot unilaterally “adopt laws regarding the exploitation of natural resources on behalf of the entire island,” as it doesn’t represent the Turkish Cypriots.

Turkey has not declared EEZs, but one map (below) showing a maximalist viewpoint and circulated amongst nationalists has been mentioned as being used to pressure the government to declare one.

Greece and Turkey have its own disagreements beside the Cyprus case. The very first issue in this context is the question of if or not the Greek islands of Crete and Rhodes have their EEZs around them. For Greece, these two bid islands have separate EEZs and Greece has right to announce EEZ around them. In contrast to this claim, Turkey suggests that these two islands have no EEZs and Turkey has sovereign right to announce 200-mile long EEZ in the Mediterranean.

There are some positive signals on the Greek-Turkish relations. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras recently (Febr, 5th) meet with President Erdoğan in Ankara[66]. Such meetings are always useful, as is bolstering the lines of communication between the two neighbors at every level. In this regard, the invitation extended by Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar to his recently appointed Greek counterpart Evangelos Apostolakis is also a positive development. Carrying its own special weight, the language of military men – the former is a general, the latter an admiral – sometimes proves more effective than that of politicians.

Territorial disputes and their tussle over oil and gas riches off the coast of Cyprus were on the agenda, in addition to the thorny issue of Greece providing sanctuary to Turkish army officers who fled the failed coup. The Greek PM described his relationship with Erdoğan as one of «respect, honesty, and directness» but noted that those ties were «challenged in very difficult moments».

Keeping channels of communication between Athens and Ankara at every moment because problems can be solved only with dialogue is the overarching message of the Greek side on this trip, as was confirmed by government representative Dimitris Tzanakopoulos.

It is indeed a pressing message at a time when Turkey is challenging Greek sovereignty in the Aegean and is interfering with the gas exploration program of the Republic of Cyprus on the grounds that Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots must be a partner to and approve of initiatives in Cyprus’ energy program.

We perceive that one important reason for this visit is Greece’s eagerness to be a part of Turkish Stream. Athen has been lobbying about this in Moscow and Moscow may very well have asked Tsipras to ‘normalize’ ties with Ankara to make Greece’s involvement to the project possible. Time to see when Erdoğan plans to visit to Athen in return.

Military involvement

The crisis between Greek Cyprus and Turkey is becoming increasingly militarized as is the whole situation in the Eastern Mediterranean. For example, according to our contacts within military and political circles in Ankara, Turkey is about to launch its largest naval exercise of the past 20 years. It is planned by the navy and air force and take place in the Aegean, eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. The exercise is called Blue Homeland (Mavi Vatan) and will be held between Feb. 27 and March 3 in an area of 462,000 square kilometers. According to the Turkish media the exercise is also a message to the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), that is planning to explore energy sources, including in disputed areas in the Mediterranean. EMGF is a coalition formed recently by Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority. This forum is long wished for by Greek Cyprus and the hope is that it may offer support for its political and energy related positions possibly also in physical defense against Turkish confrontational actions. To top off the military exercise the Turkish foreign minister announced on 21st of February that Turkey would begin drilling for oil and gas near Cyprus with two new exploration ships; stating firmly that: "Nothing at all can be done in the Mediterranean without Turkey, we will not allow that," The move is expected to inflame regional tensions with Greece. Currently Turkey is conducting several seismic surveys within Cypriotes declared EEZ's The seismic surveys are considered illegal by the Republic of Cyprus, as under international law a foreign state must request permission from the country of jurisdiction (Cyprus) to conduct any economic activity within its waters. Turkey does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus. The Turkish warship shadowing the Turkish ships is not in violation of international law as it is sailing in international waters.

In August (2018) the Turkish government decided that it will establish a naval base in Northern Cyprus in order to protect its rights and interests in the Eastern Mediterranean and to guarantee the sovereign rights of the Turkish republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). The location of the new base will be Yeni Iskele and an agreement between Turkey and the TRNC is forecasted to be signed within 2019.

So why does Ankara want a naval base in Northern Cyprus?[67] International waters of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea are running out of free space and becoming more crowded with elements of the US 6th Fleet, a plethora of naval vessels with the Russian Mediterranean Task Force, UK submarines, French frigates and others. The crisis in Syria and rivalry over hydrocarbon reserves are the main causes of this unprecedented military naval concentration and activity.

Rising tensions and naval movements have rekindled the debate in Turkey on whether to set up a permanent naval base in the Turkish part of Cyprus (the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, or Northern Cyprus). According to reports initially leaked to Turkish media, the Turkish navy has submitted a report and recommendation to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the urgent need to set up a naval base at an appropriate location there.

The report noted that in addition to ensuring the sovereign rights of Northern Cyprus, such a naval base would also guard the rights and interests of Northern Cyprus and Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean, prevent violations of maritime energy zones, and equip Northern Cyprus and Turkey with stronger cards in any negotiations that may resume.

According to Gürcan, the Turkish navy’s recommendation for a permanent naval base in Northern Cyprus is an important geopolitical development. Because such a base in Northern Cyprus will provide significant facilities for the Turkish navy. Naval experts in Ankara also believe that setting up a naval base outside of Turkish borders will provide serious self-confidence not only to the Turkish navy but also to the entire Turkish Armed Forces.

Of interest to Norway, is Turkey’s purchase of Fatih (Deep Sea Metro II) and Deep Sea Metro I from Norway[68] for deep sea drilling up to 3500 meters down to sea surface. With the purchase of these ships, Ankara has started to claim that it has sovereign right to conduct exploratory deep-sea drillings in the high seas around the island. We expect that, in the summer of 2019, these two ships are to be sent to the south of Cyprus so as to conduct deep sea drillings in the RoC’s self-declared EEZ zones. If Turkish naval elements escorts to these ships, then this move would escalate the existing tension in a rapid fashion.

Turkey - Russia