Zambia’s looming debt crisis – is China to blame?

Chinese development finance, loans and debt

Zambia’s fast-growing debt started in 2012

Three billion USD from the Eurobond market – at an increasing price

Loans from multilateral banks more-or-less steady

New loans from China and other untraditional sources

Why did Zambia borrow so much?

Inadequate economic benefit from investments

Are the Chinese loans any better – or worse?

Has Zambia national radio and TV been taken over by the Chinese?

How to cite this publication:

Arve Ofstad, Elling Tjønneland (2019). Zambia’s looming debt crisis – is China to blame? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2019:01)

Is China pressuring poor countries with debt? Debt trap diplomacy is a recent term that is used to describe Chinese loans for infrastructure and development in developing countries. Zambia is one of the countries where China is the biggest single creditor and a major provider of finance for development. It has borrowed heavily in recent years and is now in high risk of debt distress. However, the Chinese are not the main culprits for the looming debt crisis. This CMI Insight reviews the sources of the Zambian debts, examines how the loans have been used and misused, and asks whether any defaults will result in Chinese takeover of major public assets.

Main points

- China is accused of promoting debt trap diplomacy. This case study from Zambia shows that many of the dramatic claims about Chinese take-over of major state assets are exaggerated. Yet, they should not be disregarded.

- Zambia benefited from the HIPC debt relief in 2005 but has borrowed heavily since 2012 and is now in high risk of debt distress. China is the single biggest creditor, but Zambia has also borrowed from others, including the development banks and the commercial Eurobond market.

- Zambia has borrowed for important infrastructure in roads, energy, railways and telecom, while other loans have covered budget deficits. Some loans for infrastructure have had significant socio-economic benefits, while others have generated few benefits so far. Economic decision-making is centralised in the Office of the President without adequate economic considerations.

- Chinese project loans are often on a build-operate-transfer (BOT) model, resulting in Chinese or joint management for many years of specific projects, but no full take-over of whole institutions. In Zambia, this is the case inter alia for the hydropower projects with ZESCO, the digitalisation of the broadcasting service ZNBC, and two airports.

- There is limited transparency in Chinese lending and financial flows to Zambia with little accurate data on loan conditions. The Chinese approach to finance is creating incentives for kickbacks and inflated project costs that may lead to rent-seeking and cronyism. Despite government denials, “hidden loans” may also exist.

- The Zambian government must take full responsibility for the debt crisis as they have received ample warnings against the increasing debt burden from its own economists and opposition, as well as from external advisers, the IMF, World Bank and donors.

- China is concerned about the level of debt and viability of projects funded by the Chinese policy banks. This may lead to increasing attention to debt sustainability, especially in relation to concessional loans.

- Options for debt sustainability include postponing new loans and new projects, renegotiating loans from China and others, entering an IMF loan agreement, and generally more prudent financial management. The government’s approach so far has been inconsistent and too weak.

Chinese development finance, loans and debt

Over the past two decades, China has become a major source of finance for development in developing countries. The 2013 launch of China’s grand Belt and Road Initiative – a worldwide network of Chinese-funded infrastructure-development projects – reinforced this role. For some, like the US national security advisor, John R. Bolton, this is an indication of China making “strategic use of debt to hold states in Africa captive to Beijing’s wishes and demands.”[1]

China has emerged as a dominant provider of finance for infrastructure development in Africa, and is now a key player in transport, energy and telecommunications. [2] The most recent report from the Infrastructure Consortium for Africa finds that China’s role is the single biggest factor driving the higher level of funding for infrastructure in recent years.

Official Chinese statistics on financial flows to developing countries are poor and contain few details. Their lending operations are obscured by limited transparency. However, we do know that the Chinese state-owned policy banks (the Export-Import Bank and China’s Development Bank) are the main instruments. They are used to encourage Chinese companies to go abroad, and to get foreign companies and governments to purchase goods and services from China. There is solid evidence on how this has contributed to major Chinese commercial expansion in Africa and elsewhere. The evidence has also displayed the “Achilles Heel” of the Chinese approach and financing model: China’s control over the banking system and the close ties between the state and available funding may encourage investments, but it is also a model that relies heavily on Chinese companies developing projects together with host country officials. This model creates strong incentives for kickbacks and inflated project costs and may lead to rent-seeking and cronyism.[3]

China has an expanding development aid budget coordinated by a dedicated aid agency. Many of the disbursements are linked to lending from the two policy banks and to Belt and Road projects in selected countries. Details and the country breakdown are not provided, but the two most recent Chinese white papers on aid (from 2011 and 2014) provide the global figures. More than half of the aid budget are concessional loans (subsidising interests on commercial loans from the policy banks), typically infrastructure and economic development projects. A further 10% constitutes interest free loans, typically spent on major public and government buildings, stadiums and so on. Some have also been used for infrastructure, such as the railway between Zambia and Tanzania in the 1970s. Historically, these interest free loans have been cancelled when they mature. The remaining part of the Chinese aid is provided as grants – mainly to agriculture, health and education sectors.[4]

Debt sustainability

China’s expanded lending to developing countries contributes to increased debt. Debt sustainability has become an issue because of the sheer scale of Chinese loans posing a risk for failed projects and the misuse of funds. Careless borrowing for infrastructure could lead to balance of payments problems. Most countries borrowing heavily from China have histories of IMF bailouts, and unsustainable debt due to new such borrowing has become a main issue in some Central and South Asian countries[5].

The most frequent example is the case of the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka. The Sri Lankan government secured in 2007 finance from China’s Export-Import (EXIM) Bank to develop the port. In 2015, however, Sri Lanka had to arrange a bailout from the IMF although the Chinese loans only accounted for some 10% of the debt. The government sought to raise cash by privatising state-owned assets, including a major stake in Hambantota port. A Chinese company was the successful bidder and bought 70% of the shares. The Sri Lankan government used the proceeds to make payments on the Chinese loans as well as other debt service (Bräutigam 2019). Chinese companies have made similar investments in other ports being privatised, e.g. the container terminal in Piraeus in Greece and the Zeebrugge Terminal in Belgium.

Chinese lending to Africa has made China a major creditor in several African countries. The China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) in Washington has examined the situation in 17 African countries who are either in debt distress or in high risk of debt distress. It notes that eight countries have received relatively small Chinese loans, and six have received more substantial loans. Chinese loans are major or dominant in three countries: Republic of Congo, Djibouti and Zambia.[6]

The high volume of the lending has forced China to address the issue of debt sustainability. This is handled in bilateral arrangements, mainly through rescheduling or new loans, but there are also a number of debt cancellations. However, most of the debt cancellations appear to be linked to China’s aid-funded interest free loans and are typically for smaller amounts (less than USD 100 million).[7] It is also noteworthy that there have been several recent examples of China becoming more careful in providing loans to Africa. China now admits that the planning of some of its major infrastructure projects abroad, was “downright inadequate,” and led to huge financial losses. A good illustration is China’s funding to the Kenyan government for the two first phases of the railway that connects Mombasa port with Nairobi, and then onto Uganda. The Chinese government has refused two attempts by Kenya to secure Chinese funding for the final leg beyond Nairobi connecting to the landlocked countries of the Great Lakes region.[8]

Djibouti has emerged as a new investment destination for China in Africa. Djibouti has a strategic location. It is at the entrance to the Red Sea, close to the transit routes of the Suez Canal shipping, and to the Horn of Africa and the Arab Peninsula. Djibouti has attracted several military tenants (the US, France, Italy and others). China opened its first military base outside China in Djibouti. China sees Djibouti as a potential hub for transhipment, industrial processing and duty-free wholesale. It has provided major funding for the development of a multi-purpose port connected to the Djibouti-Ethiopia railway terminal and funded the railway to Ethiopia. Today, Djibouti is at high risk of debt distress with perhaps two-thirds of the country’s debt being to China (Eom et al 2018).

The case of Zambia

Zambia’s debt is one of the fast-increasing ones in Africa. China is a major creditor. Several stories are circulating on China taking over essential infrastructure and central institutions as a result of the debt. Africa Confidential reported on 3 September 2018 that “The state electricity company Zesco is already in talks about a takeover by a Chinese company, AC has learned. The state-owned TV and radio news channel ZNBC is already Chinese-owned.” Others have added that Lusaka airport may also be taken over by the Chinese. The reality is a lot more nuanced. It is nevertheless correct to say that Zambia has a looming debt crisis; but the Chinese are not the main culprits.

Zambia’s fast-growing debt started in 2012

Zambia’s external public debt has risen dramatically in recent years, particularly since 2012. According to official figures, the debt reached 9.4 billion USD by mid-2018.[9] In addition, the government guaranteed for loans to its state-owned companies totalling 1.2 billion USD. Several critics and alternative sources claim that the figures may be even higher. These figures only account for the external borrowing. The government also had domestic debt of approximately 5 billion USD, and outstanding arrears of approximately 1.2 billion USD. The joint IMF/World Bank debt sustainability assessment concluded in October 2017 that Zambia was under a “high risk of debt distress”. The government’s own assessment in early 2018 came to the same conclusion. The total external debt had reached close to 40% of GDP according to official figures, while the domestic debt and arrears represented some 23%. Domestic debt is a considerable problem and leads to high interest rates and to out-crowding of local entrepreneurs’ access to credit. However, domestic debt is handled differently than external debt, and we shall not deal with domestic debt here.

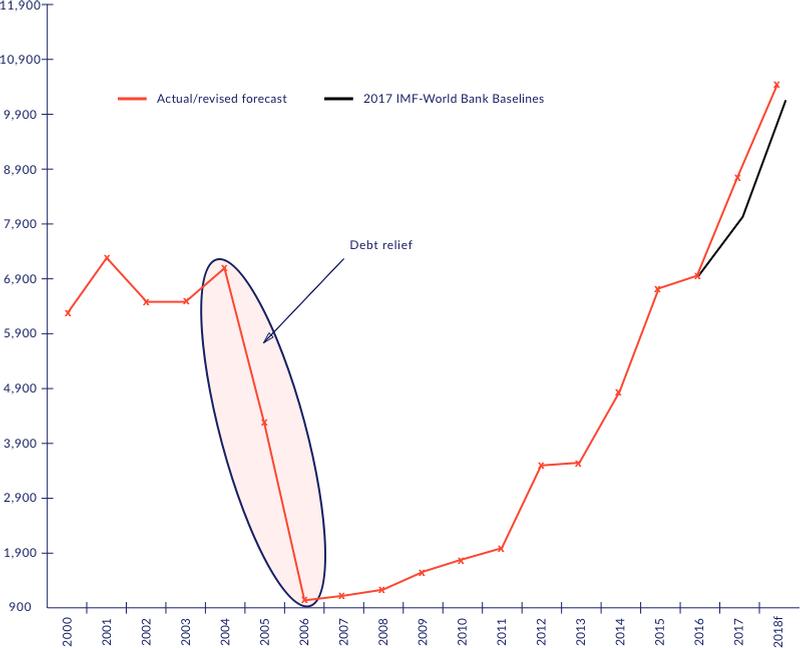

External public dept: excluding publicly guaranteed and arrears (US$ millions)

Source: Zambia Ministry of Finance, IMF and World Bank

Zambia benefited from the World Bank/ IMF-organised debt relief under the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative. Practically all external debt was cancelled in 2005. Thus, the rapid accumulation of external debt is particularly worrisome.[10] Until 2011, Zambia limited its borrowing while the economy had grown 6-7% annually since 2002. By the end of 2011, when the Patriotic Front (PF) government won the elections and took power, the external debt stood at only 1.9 billion USD or 8.4% of GDP, according to official and World Bank sources.[11] Since 2012, however, the PF government has borrowed more than four times this amount.

Most loans in the 1980s and 90s, and even up to 2011, were provided by multilateral banks such as the World Bank/IDA and the African Development Bank (AfDB) and other development donors on concessional (low interest) terms. The new loans, however, are mostly on commercial terms, meaning higher interests and shorter time frames. The main new sources for the Zambian loans are the commercial Eurobond market, and Chinese credits and loans, as well as banks in India, South Africa, Nigeria and the Arab world.

Three billion USD from the Eurobond market – at an increasing price

In 2012, Zambia followed the example of several other African countries and decided for the first time to raise money in the Eurobond market at commercial rates. The response was very positive. The first 750 million USD loan was quickly over-subscribed, and the interest rate was a reasonable 5.6%. However, the loan must be repaid in full within ten years. Encouraged by this relative success, Zambia managed a second Eurobond loan in 2014, this time borrowing 1 billion USD even though the interest rate had jumped to 8.6%. Despite the high price, Zambia decided to go for a third Eurobond loan in 2015, and borrowed 1.25 billion USD at a 9.4% interest rate. Zambia has thus altogether borrowed 3 billion USD at commercial rates and has to start heavy repayments in 2022. The then Finance Minister made a statement promising to create a “sinking fund” i.e. savings to enable repayments in time. However, Zambia has not yet been able to save anything into this fund. Instead, they have started to look for ways to extend the loan period or enter into new loans to be able to repay the present ones. As the year 2022 is approaching, this is becoming more urgent.

Loans from multilateral banks more-or-less steady

The “traditional” loans from the multilateral development banks have not increased much in recent years, and were 1.6 billion USD at the end of 2017.[12] These are mostly loans with practically no interest and long maturity. IDA credits from the World Bank represent around 900 million USD, and the African Development Fund around 430 million. In addition to a small loan from the IMF, the multilaterals thus represented less than 20% of the external debt at the end of 2017.

In 2011, Zambia was “elevated” from being a “low-income” to a “lower middle-income” country, according to World Bank definitions based on GDP per capita. Therefore, it can no longer borrow at the very low concessional rates under the IDA-only and the African Development Fund, but has to mix these with the closer-to-market loans. Zambia was less keen on borrowing on these new terms. Since 2012, Zambia has not entered into any new loans from the IMF.

New loans from China and other untraditional sources

Zambia has borrowed from several non-Chinese sources, including bilateral government loans, loans from fuel suppliers, the Arab Development Bank (BADEA), Israeli sources (for defence purposes) and from regular international banks in the UK, Nigeria and South Africa. Most of these loans probably have commercial market conditions.

Meanwhile, Zambian borrowing from Chinese sources has increased dramatically in recent years. Starting from a relatively low figure in 2011, it reached at least 2.3 billion USD at the end of 2017 according to official sources (Ministry of Finance 2018). The major creditor is China’s EXIM Bank. Other loans have been obtained from China Development Bank and China National Aero-Technology Import & Export Corporation (CATEC). The EXIM Bank and the Development Bank provide loans on partial concessional terms, and are thus less costly than commercial terms.

However, the official figures on Chinese loans are much lower than those estimated by the China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) at Johns Hopkins University. CARI found that Zambia had accumulated loans from China totalling almost 6.4 billion USD at end-2017.[13] If this figure is correct, Zambia may have a total debt of 14.7 billion (including state guaranteed loans), of which Chinese loans account for some 44%.

As with the official Zambian figures, it is difficult to assess the accuracy of the CARI figure. They aim at reporting only confirmed figures and actual disbursements rather than commitments, while adding that they do not have sufficient information on repayments. They are also uncertain about whether the loans are fully guaranteed by the state, as they may have been granted to entities organised as “Special Purpose Vehicles” (SPV) such as the hydropower plants.

According to CARI, Zambia borrowed only small amounts from China up to 2009, but in 2010 they may have borrowed 1.2 billion USD. This figure is not recorded in official statistics, and it is unclear how this loan was used. It was the year before elections in 2011 and may have been secured by the then ruling party MMD to boost their popularity. Loans in 2011 were lower, possibly awaiting the outcome of elections. In the following years, borrowing from China started to increase again, and reached almost 1 billion USD in 2015 and nearly 2 billion in 2016, according to CARI. These are very high figures, and again not fully reflected in the official figures on foreign debts.

Hidden loans?

Several critics have raised the question of whether Zambia has “hidden loans”, similar to those disclosed in Mozambique recently. In Mozambique, the disclosure led to an economic crisis and major conflicts with donors who provide budget support and other grants. The IMF uses the official figures provided by the government, but they also feel uncertain about the accuracy of Zambia’s official statements regarding outstanding loans and new commitments. This is one of the reasons why negotiations on an IMF loan stalled in 2017. In August 2018, the government asked IMF to withdraw its representative Alfredo Baldini, claiming that he was supposedly 'spreading negative talk' on Zambia’s debt situation.[14]

The main issue seems to be borrowing from China and other sources for special projects organised by various state agencies. If the loan is to be repaid from income generated directly by the project, the responsibility of the government may be unclear. Without a clear government guarantee, the loan is actually more similar to an investment in a competitive enterprise.[15]

Zambia has recently published some of their loans for military and security purposes, but most of these are usually kept secret from the general public. Therefore, the amounts involved are uncertain.

In 2017, a former Vice President and present leader of an opposition party, Nevers Mumba, claimed that Zambia’s real debt may be as much as 30 billion USD or even higher. Just three days later, however, Mumba admitted a gross miscalculation. He had included two loans amounting to 20 million as 20 billion.[16] As he had “forgotten” the Eurobond loans of 3 billion, he concluded that the external debt was 16.7 billion. Adding the domestic debt, the total debt reached 23.4 billion. His revised figure is still much higher than the official figures, but not quite as sensational. The explanation is partly that he added all new loan commitments, whether actually disbursed or not. He included some that were at a very preliminary stage, such as the Chipata-Serenje railway line at 2.3 billion USD, which has now been postponed. For other projects, he may have mixed total costs and how much is to be borrowed. Mumba’s point that loan commitments will have a cost in the future, if realised, is correct. However, his (mis)calculations also illustrate how various figures may easily be used, and misused, for political purposes.

Finance Minister Mwanakatwe issued a strong statement in April 2018 denying that Zambia had any hidden loans. She added that Zambia had not defaulted on any of the Eurobond interest payments or on any of the Chinese loans. Furthermore, she stated that “the issue of debt from China has been grossly misrepresented by some members of the public.”[17]

In Zambia, however, major economic decisions are primarily made in the Office of the President (often just described as “State House”), rather than in the Ministry of Finance. While the state budgets presented to Parliament make reasonable sense and highlight priorities and good financial management, the President and his advisers, under various political pressures, decide on actual spending. This became very clear under President Sata (2011-14) and has more-or-less continued under President Lungu. Former Finance Minister Chikwanda (2011-2016) may have found borrowing to be the easy way out, rather than opposing the President’s expenditures. In addition, even though all state-guaranteed loans in principle should pass through the Ministry of Finance and be approved by Parliament, this has not always been the case.

The more recent Finance Minister Felix Mutati (2016-18) and the current Minister Mwanakatwe (since 2018) may have been trying harder to control the economy which is drifting into a heavy debt dependency. It remains to be seen how Mwanakatwe will manage.

Why did Zambia borrow so much?

Zambia had a relatively healthy macroeconomic position in 2011, resulting from a high economic growth since 2002 and a sound government budget. However, the growth had a relatively small impact on living conditions for the majority. The reduction of the poverty rate was limited. Unemployment and unrest were growing, especially among the urban youth. The change of government in 2011 created high expectations of a broader growth, and the new PF government in response initiated a high number of construction projects.

Numerous road projects were started, some have since been completed, while several have stalled and been left half-finished. Among the most spectacular projects are the expensive Mongo-Kalabo road crossing the Zambezi flood area in Western Province, a four-lane highway to the Copperbelt region, and the bridge crossing the Zambezi from Kazungula in Southern Province linking Zambia directly with Botswana and Namibia.

In addition to road building, the PF also borrowed for other infrastructure purposes, such as a new terminal for the Lusaka airport and a new airport in the Copperbelt (Ndola). Funds were also allocated for improvement of the railways, which had been de-privatised and reorganised as a state-owned company. Other loans were for hydropower plants including the Itezhi-Tezhi on the Kafue river, additional turbines in the Kariba Dam, and a major new plant to be constructed in Lower Kafue Gorge.

Most people agree that borrowing for investments in infrastructure is necessary for developing countries as it makes trade and travel easier, providing improved access. The economy will grow with improved transport and communications and a stable energy supply. China strongly emphasises the importance of infrastructure. In earlier decades, Western development aid contributed heavily to infrastructure development including roads, energy and telecommunications. The main development banks still do this. The basic thinking is that a country with economic growth will be able to repay such loans.

Inadequate economic benefit from investments

However, in Zambia several factors have inhibited many of these positive effects. Zambia is growing its debts without yet seeing enough benefits from its investments. First, there was hardly any systematic priority for which roads were most needed. Second, the contracts were in many cases awarded without proper tendering, partly because of tied funding from Chinese banks. Third, the cost of construction was often very high compared to neighbouring countries. There is strong suspicion that decision-makers in or close to the President’s office benefited from such contracts.

The energy sector has also been unable to cover the costs of its loans. This is mostly because the state-owned energy company ZESCO was not able to increase its electricity tariffs to the major mining companies in line with its higher costs, and for political reasons was not allowed to increase tariffs for other customers.

However, not all loans have been spent on infrastructure or other investments. Zambia has also borrowed to cover its growing budget deficit while maintaining an expansionary budget policy. The budget deficit started to grow in 2013-14 as the economic boom from previous decade was fading. The following year, falling exports earnings from the mines combined with crisis in the power generation contributed to high-cost imports of electricity, a major drop in the exchange rate for the Zambian kwacha, and inflation beyond 20%. Meanwhile, government expenditures continued to expand. Despite efforts to strengthen public financial management, budget discipline was poor. As a result of the deteriorating financial management, international donors stopped further budget support when the agreements came to an end in 2013 and 2014.

Are the Chinese loans any better – or worse?

China has tried to present itself as a donor that is different from the Western and multilateral donors and development funders. They claim that they provide grants and loans for development purposes without political conditions and that their terms are more beneficial. They claim to be on more “equal terms” since China is also a developing country.

However, China is also less transparent in its finances and aid, and these challenges are apparent in Zambia. It is difficult to obtain information about the actual figures and the full terms and conditions for their loans and development support. In many cases, contracts were awarded to Chinese contractors without public tendering. Accusations regarding “gifts” and corruption are rife. The Chinese packages may seem to be “too good” not to be accepted. It is nevertheless the responsibility of the Zambian decision-makers to ensure that they get value for money, to make a full assessment of the terms of any contract and loan agreement and to make sure that the borrowing is sustainable.

China has funded several spectacular projects in Zambia such as two big football stadiums in Ndola and Lusaka and the new government complex conference centre in Lusaka. While these have been partly financed by grants and interest-free loans, none of them will generate enough income to cover their costs. The Chinese have also funded major housing complexes for Zambia Police Services and the Zambian Air Force. It is particularly difficult to know the terms of the funds for the security forces.

The energy projects

In the energy sector, China funded additional turbines on each side of the Kariba dam. Although they were only supposed to be used during high floods, it seems as though they were used extensively during 2014 to increase the revenue for ZESCO and its sister utility in Zimbabwe. This contributed to the serious lack of electricity in 2015.

The Chinese funding for the major 750 MW hydropower station at Kafue Gorge Lower may illustrate the relationships and considerations involved. The power plant had been planned for several years and a memo of understanding was finally signed under the MMD government of President Banda. The construction was to be undertaken by the Chinese SinoHydro company with full Chinese funding. However, after the change of government in 2011, the new Minister of Finance questioned whether such a complete package was beneficial to Zambia and whether there were sufficient transparency and control mechanisms in place. He also wanted a second opinion on the technical solutions proposed by the Chinese. Norway was requested to review the plans and give further advice, but the Norwegian Ministry did not wish to be involved in such a task.[18] Zambia nevertheless decided to “unpack” the original proposal and looked for alternative funding and investors. They even broke the agreed MoU with SinoHydro at the political risk of annoying its relations with China.

Following further negotiations, Zambia ultimately provided a share of funding from its own sources (from the Eurobond loans), but the China-Africa Development Fund (a subsidiary of China Development Bank) remains the major funder. After an open tendering process, SinoHydro re-won the contract. The total costs are stipulated at around 2 billion USD. This time, however, ZESCO engaged a Norwegian private company, Norconsult, to act as their technical advisors and quality controller to ensure that SinoHydro and other contractors operate within contracts and international standards. SinoHydro lists this as a Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) project, implying that they intend to operate the power plant for some years after completion of construction.

In another case, SinoHydro won an open tendering to construct the Itezhi-Tezhi hydropower plant and extend the dam on the Kafue river. This time without any Chinese funding. The power plant is owned jointly by ZESCO and the Indian Tata company, and was funded by a consortium of development banks including the African Development Bank, the Dutch FMO, the French PROBARCO, the South African DBSA, the European EDB and the Indian Ex-Im Bank. It was completed in 2015, and Tata and ZESCO will operate the plant on a BOT basis for 25 years.[19]

Has Zambia national radio and TV been taken over by the Chinese?

The Zambia National Broadcasting (ZNBC) is a state-owned enterprise and has been running a deficit for many years. According to the most recent report from the Zambia Auditor General, it owes money inter alia in taxes and pension payments.[20] StarTimes of China entered Zambia in 2011 during the previous MMD government when the StarTimes subsidiary Star Software Technology won a 220 million USD tender that covered the design, supply and commissioning of the country’s national digital terrestrial broadcasting system. The PF government, however, cancelled the contract two years later, citing irregularities in the awarding process. They also wanted to split the contract into four parts, covering civil works, studios, network and consultancy services.

In 2014, StarTimes was nevertheless awarded a new and smaller contract of 9 million USD for phase I of the migration.[21] Then in 2016, ZNBC and StarTimes of China agreed to establish a joint venture company called Topstar Communications Company Ltd. ZNBC will own 40% while StarTimes will own 60% during the initial 25 years. The purpose of this joint venture is similar to the 2011 contract: the digital transformation of ZNBC, including the provision of decoders. In December 2016, the Zambian government signed an agreement to borrow some 232 million USD from China’s EXIM Bank to fund this digitalisation and to build more studios for ZNBC.[22] The terms were similar to many other EXIM credits; 2% interest rate and a 20-year repayment schedule after a 5-year grace period without instalments. As in most cases in Zambia, rumours circulated that some decision-makers involved in the deal received a “share”.

However, as the Auditor General has pointed out, ZNBC had no repayment plans. The first interest payment of 2.3 million USD due in July 2017 was not paid on time, presumably because all the agreements and arrangements had not yet been finalised. According to other sources, the interest payments have started.[23] The full agreement only became known to the general public in Zambia in October 2017 when the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission confirmed that they had approved the establishment of the joint venture, which they erroneously termed a “merger” between ZNBC and StarTimes. The ZNBC remains a separate institution, fully owned and controlled by the state. The loan is to be repaid with income generated by Topstar from sales of decoders, subscriptions and advertisements.

The Chinese StarTimes has thus taken over some of ZNBC activities, and will manage Topstar until the loan has been paid in full. They have not taken over the whole of ZNBC, however.

Topstar and ZNBC illustrate China’s growing role in telecommunications in Africa. Chinese StarTimes is identified by the Chinese Ministry of Culture as a “Cultural Exports Key Enterprise”, and as the only private Chinese company that has been authorised by the Ministry of Commerce to go into projects in foreign countries’ radio and TV industry. The EXIM Bank provided the company with a 163 million USD loan in 2012 to help it expand its operations in Africa. In June 2014, it received an additional 60 million USD loan for the same purpose. The Development Bank’s China-Africa Development Fund has become StarTimes’ second largest shareholder. The Fund has extended a 220 million USD loan to the StarTimes’ African operations.

The Beijing-based StarTimes Group is now one of Africa’s most important media companies with 10 million subscribers across 30 countries. It dominates the market for digital TV and pay-TV along with the French Canal Plus and South Africa’s Multichoice/DSTV. StarTimes also has a continental centre for TV and film production in Nairobi. Their productions are translated into many African languages. StarTimes also support organisations like UNAIDS and SOS Villages as part of their corporate social responsibility.

StarTimes is a main actor in Africa’s transition from analogue to digital television. Its Zambia deal is typical for how it operates; it facilitates an attractive Chinese loan and strikes a deal with broadcasting authorities. Many of the deals in other African countries have been met with protests and accusations of opaque deals between StarTimes and ministers of communications, telecommunication regulators and state-owned broadcasters. African authorities have also cancelled some deals, as in Ghana.[24]

What happens if Zambia does not service the loans?

Zambia is already in high risk of debt distress. The present economic growth at around 3-4% annually is only slightly above the population growth –meaning that there is hardly any growth per capita. Zambia will have to manage its budget a lot more carefully to avoid deepening the crisis, at least until it succeeds in accelerating growth and generate more revenues. In late 2017, the government announced an “Economic Stabilisation and Growth Programme” (ESGP) to mobilise domestic revenues (taxes) and allocate more of the public spending to core public sector tasks. The programme sought to minimise unplanned expenditures, improve transparency, and ensure more policy consistency. However, the concrete measures to follow-up have been weak and actual spending has deviated from the plan.

Postponing new loans: Regarding the external debt, the first option is to reduce or postpone future borrowing and to not make full use of loan commitments. In 2018, Finance Minister Mwanakatwe announced that ongoing projects that were not yet at least 80% complete, should be postponed or delayed. This was part of the government’s “Debt Restructuring Programme” and the ESGP. Planned projects such as new railway lines have been cancelled or postponed. However, several of the unfinished (road) projects were implemented by Chinese contractors, and President Lungu soon after felt it necessary to reassure China’s ambassador that there would be “no disruption in the ongoing projects” financed by China.[25]

Refinancing: The second option is to refinance some of the more expensive loans to obtain better terms and/or longer maturity. Zambia is already trying this option by negotiating with Chinese banks and authorities, as well as trying to refinance the Eurobond loans. Refinancing may extend the loan period, but may also increase the interest rates thereby increasing the costs and pushing the problem into the future.

Borrowing from IMF: An IMF loan would be part of this second option since it would imply refinancing – but on lower interests than the commercial market. Taking this loan would also be a strong signal to analysts that Zambia tries to revise its economic policies to move away from the brink of the debt trap, and become creditworthy for regular borrowing and investments. This would be beneficial for further economic development, despite the fact that the envisaged 1.3 billion USD loan would only cover part of the present debt.

Meanwhile, the government has still not been able to convince IMF that its debt restructuring programme and the economic stability and growth programmes are sufficient to move the country away from its high risk of debt distress. While the political statements may be good enough, the government has still not shown in practice that it will deliver. In particular, the issue of “hidden” debts and various unpaid bills and arrears still lingers, and the government continues to take on new commitments and extra-budgetary expenses.

At the same time, the memory of the previous deals with the IMF in the 1990s, which resulted in the HIPC debt relief, is still alive. Many in Zambia, including parts of the government, viewed this as “dictates” by the World Bank and IMF resulting in privatisation of major state-owned companies and drastic cuts in government expenditures. Many claim that this also resulted in deteriorated social welfare, while in reality the economic crisis in the previous years (during the Kaunda period) was the main cause for the breakdown of the social services in health and education. The scepticism and negative attitudes towards the IMF remain, despite the different conditionalities this time from the IMF side.

Chinese options: The Chinese options may be different. Zambia is already actively negotiating refinancing, and several ministers travel regularly to Beijing for this purpose. The Chinese banks and other creditors are not so different from other creditors, and they want their money back. In the past, the Chinese government may have bailed them out for political reasons, and actually provided debt relief. This may not be so easy in the future. We expect that some of the Chinese loans – the interest-free loans funded by Chinese aid – may be cancelled, but such loans only account for a small share of total debt to Chinese creditors.

As described above, several Chinese loans have been provided for joint ventures or on BOT terms. In these cases, the Chinese partner will be co-owner and/or manager until the loan has been repaid. In such cases, the risk is shared, and the Chinese partner is co-responsible for economic returns and effective management. This may contribute to a more predictable relationship.

In other cases, it seems that the Chinese loans are secured by collateral assets, which may be possessed if there is a default on the loan. What may happen if Zambia defaults on the new airports in Lusaka and Ndola is unclear, but most likely these will be managed on a BOT basis until the loans have been fully recovered.

Concluding remarks

Zambia’s growing external debt has resulted in a “high” risk of debt distress only 12 years after receiving full debt relief under the HIPC scheme. Since 2012, Zambia has borrowed extensively. The primary lending sources have been the Eurobond market and Chinese creditors, but Zambia has also borrowed from other non-traditional and commercial sources. The loans have been used both for major infrastructure investments and to cover an increased budget deficit. Poor economic management combined with centralised decision-making in the Office of the President and likely illicit payments to politicians and other decision-makers have contributed to the continued accumulation of debts. The government has disregarded strong warnings from independent economists and the opposition, as well from external actors, including the World Bank, IMF and international donors. It must therefore take full responsibility for the looming debt crisis.

Various media outlets have made dramatic statements on alleged hidden debts and Chinese take-over of central state-owned institutions. These statements have often turned out to be exaggerations, but should not be disregarded completely. Chinese partners have entered into joint ventures and will manage new investments on a build-operate-transfer basis for several years. However, Zambia needs to be much more careful in managing its economy and should avoid further irresponsible commitments to escape the more dramatic outcomes of major defaults, whether this affects the Chinese or the non-Chinese creditors.

The discussion has also revealed another important dimension: there is little transparency in the Chinese lending operations. Neither the full scope of the loans nor the conditions are fully known. This leads to much uncertainty and speculations. China has, through its state-owned policy banks, made it relatively easy for Zambian authorities to access loans and credits. This gives Chinese companies and the Zambian officials scope to identify and design projects and creates incentives for kickbacks and inflated project costs that may lead to rent-seeking and cronyism. It is a major challenge for Zambia, and other African governments, to counteract such incentives through transparent and strong financial management control systems by the Ministry of Finance, parliament and by other governance bodies.

Meanwhile also the Chinese state-owned lending banks and other commercial creditors have an obligation to assess the viability and quality of their project lending as well as the sustainability of the debt burden on the borrower.

Notes

[1] “Remarks by National Security Advisor Ambassador John R. Bolton on the Trump Administration’s New Africa Strategy”, given at the Heritage Foundation, Washington DC, 13 December 2018

[2] See the most recent (2017) report from this World Bank/African Development Bank dominated consortium - Infrastructure Financing Trends in Africa – 2017

[3] See also D. Bräutigam (2019), “Crony capitalism. Misdiagnosing the Chinese infrastructure push”, The American Interest, 4 April

[4] Global figures are provided in the 2011 and 2014 white papers, but the guidelines are repeated in the current 2018 draft guidelines for the new Chinese aid directorate, reproduced in the China Aid Blog

[5] See also G. Wignaraja et al. (2018), Asia in 2025. Development prospects and challenges for middle-income countries, London: Overseas Development Institute (Report, September).

[6] See Janet Eom, Deborah Bräutigam, and Lina Benabdallah (2018), The Path Ahead: The 7th Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, Washington: SAIS-CARI (Briefing Paper No 1, 2018).

[7] See more on this in Oxford China Africa Consultancy (2019), China: Debt Cancellation, consultancy report 17 April, prepared for the Beijing-based Development Reimagined

[8] See also “Kenya fails to secure $3.6b from China for third phase of SGR line to Kisumu”, The East African 27 April 2019

[9] 2019 Budget Address by the Minister of Finance, Margaret Mwanakatwe, delivered to Zambia National Assembly 28th September 2018.

[10] Caleb Fundanga, a former Governor of Bank of Zambia and presently Executive Director at Macroeconomic and Financial Management Institute of Eastern and Southern Africa, is among those concerned. See inter alia Caleb M. Fundanga (2017): Public debt trends in Zambia and prospects for long term debt sustainability. Harare: MEFMI 23p.

[11] Nevers Mumba, a former Vice President and leader of one faction of the opposition MMD party, claims that the debt at end-2011 was 3.5 billion USD or 15 % of GDP. See Lusaka Times 28 July 2017

[12] Ministry of Finance (2018): Zambia Economic Report 2017.

[13] Statistics tables found at SAIS-CARI website

[14] “IMF Rep’s open talk on debt angered govt” in The Mast 28 August 2018

[15] Zambian independent researchers also have challenges in accessing information. See Trevor Simumba (2018): He who pays the piper: Zambia’s growing China debt crisis. Lusaka: Centre for Trade Policy and Development.

[16] “Zambia’s hidden debt crisis Part 2: Alternative calculations put debt at $23.4 billion (and counting)”, Lusaka Times, 31 July 2017

[17] “Zambia is not hiding its debts – Mwanakatwe”, Lusaka Times, 14 April 2018.

[18] Based on personal knowledge.

[19] This case is well described in J.Hwang, D.Bräutigam and N.Wang (2015): Chinese Engagement in Hydropower Infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa, The SAIS China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkin University, Working Paper 1, December 2015, p20.

[20] Report of the Auditor General on the Accounts of Parastatal Bodies and other Statutory Institutions for the Financial Years ended 31st December 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 pp 196-206.

[21] See “Zambia contracts with StarTimes for DTT broadcasting system”, Digital TV News, July 10th, 2014.

[22] According to press releases, the government signed a contract for 273 million USD in September 2015, while the minister of information and broadcasting stated in July 2017 that this amount had still not been disbursed. The actual figures involved are therefore unclear. Lusaka Times, 19 September 2015 and 29 July 2017.

[23] “ZNBC Takeover Dispute: Topstar is a Viable Project and must be Supported – Lusaka Lawyer” in The Zambian Observer (online) 24 October 2018.

[24] See more about StarTimes and Africa in Helge Rønning & Elling Tjønneland (2018), China and Telecommunications in Africa, Paper Presented at the Conference China-Africa in Global Comparative Perspective, 27-29 June 2018, Université Libre de Bruxelles.

[25] Press statement issued by State House, Lusaka, 11th July 2018: “President assures China over debt management”. See article “There will be no disruption to Chinese funded projects or financing – Edgar Lungu” in The Zambian Observer (online) 11 July 2018.