Negotiating access to health care for populations affected by conflict

Health care in humanitarian crises

Negotiating access to health care and humanitarian diplomacy

Tools for humanitarian negotiations and diplomacy

1. Theoretical and contextual knowledge

How to cite this publication:

Raju Sira Mahalingappa Guru (2021). Negotiating access to health care for populations affected by conflict. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Working Paper WP 2021:6)

Abstract

This Working Paper seeks to understand the tools required to allow negotiations for the access of health care by populations affected by humanitarian disasters. A review of theoretical knowledge about health negotiations together with resource materials relating to negotiation and document analysis found that humanitarian organisations lack robust, evidence-based, context-specific negotiation models and tools for accessing humanitarian spaces that allow health care in conflict situations. There is little academic research on humanitarian negotiations as they relate to health care and the protection of medical missions. However, humanitarian organisations have begun to realise the importance of humanitarian negotiations and the use of diplomacy in conflict situations and are beginning to forge partnerships with like-minded organisations, including academic institutions and think-tank groups in order to develop appropriate negotiation tools and methods. They are also establishing peer networks and training frontline humanitarian staff to address the needs of those staff and their organisations. The tools they are using, though, are based on resource materials specific to other fields. The Naivasha Grid offers a systematic and useful guide for enhancing negotiations for health care access in crisis settings.

Background

During a humanitarian conflict or crisis, medical infrastructures and medical services are usually partly or entirely destroyed. In these circumstances, local and international humanitarian organisations respond to provide life-saving medical, water and sanitation services to populations that are affected. Gaining access to humanitarian space through negotiation with belligerent states, non-state actors and state authorities is difficult and challenging. Most humanitarian staff and the agencies for which they work have both good and bad experiences of negotiation with the stakeholders involved. This negotiation is a challenge for every humanitarian professional. It is an art as well as a science, and it requires knowledge and experience of the context, stakeholders and tactics. Humanitarian negotiation is multidimensional, multicultural and varies from region to region; it depends on the type of organisation and their mandates, as well as the culture of the region in which the negotiation is taking place. While negotiating, the humanitarian ‘diplomat’ has the moral obligation to preserve and protect humanitarian principles while gaining access to the affected population. The diplomat also negotiates from a position of weakness, often with no power, influence or resources to convince other players, and this will always be a painful and difficult process.

Most humanitarian organisations that are involved in providing medical services to affected populations understand the importance of and the need for negotiation and diplomacy in their activities, but only a few large organisations have written humanitarian diplomacy policies with clear objectives. Other organisations conduct negotiations that are dependent solely on their vision document or a specific country’s policy document. Humanitarian organisations recognise the importance and usefulness of tools such as stakeholder analysis, risk analysis, risk mitigation and logical frame analysis in their daily operations and activities; but there is a lack of practical, evidence-based negotiation tools that frontline humanitarian workers can use in their regular field negotiations. However, some humanitarian organisations have developed policy guidance documents and field manuals on humanitarian negotiation as resources for their field staff. There has also been discussion about creating training materials and tools, documenting best practices of negotiations from the field as case studies and conducting training for future trainers.

There is a paucity of research and theoretical knowledge in the area of negotiation and access to health care, and a need to document challenges and lessons learned from various conflict contexts. Most examples in negotiation theories are adopted from the areas of law, international relations, business, mergers and acquisitions, and nuclear deterrence. Understanding the intricacies of negotiation in accessing health care can provide better understanding of stakeholders and their interests, and the various strategies that frontline workers can adopt to gain humanitarian access.

Health care in humanitarian crises

During a humanitarian conflict or crisis, one of the first things affected is the medical infrastructure, which causes the displacement of health care workers. Health care facilities are either destroyed entirely or left dysfunctional, being forced to close (Nonprofit Quarterly, 2017), with local medical personnel being among the victims who rush to seek refuge. Health workers, the facilities in which they work and other health resources face attacks when settings are fragile, affected by conflict and vulnerable (ICRC, 2015; WHO, 2020). Often, foreign aid is refused or humanitarian organisations are asked to close projects because of national and international political agendas. This is evident in the major refugee crises of 2021, among the Rohingya, Syrian and Afghanistan populations. The complex geopolitical and humanitarian situations in Myanmar, Syria and Afghanistan have challenged humanitarian access to routine and specialist health care among their respective refugee populations (MSF, 2018; UN, 2018; UNSC, 2018). Negotiating humanitarian space in conflict settings is both challenging and difficult, and often organisations do not succeed in achieving the desired access owing to geopolitical and security issues, control by non-state actors and mistrust of relief organisations and their intentions.

Access to health, water and sanitation is one of the first interventions that most humanitarian organisations and governments want to provide to affected populations (UNOCHA, 2018). This is not easy in areas affected by regional conflicts, besieged cities or regions controlled by non-state actors where the host government is hostile towards the population. In addition, the average length of a major refugee situation has increased from nine years in 1993 to seventeen years in 2003 (UNHCR, 2004). This brings additional economic burdens and domestic political pressure to provide health care and other life-saving interventions. The average length of a war is currently thirty-five years (Uppsala Conflict Data Program, 2018), and it is clear that current and future conflicts will be protracted, with no clear winners or losers. Given these facts, humanitarian organisations must have long-term, multi-year strategies to address humanitarian issues through negotiation.

Negotiating access to health care and humanitarian diplomacy

Negotiating access to medical missions includes acquiring permission to open clinics and hospitals, and to set up immunisation programmes. It involves making contact with local community leaders, religious leaders and non-state actors, and also engaging with the affected population to build trust and acceptance. This is done by providing independent and impartial medical services, while being aware that these facilities and their patients might be attacked. These attacks, both on medical services and aid workers, are increasing (Humanitarian Outcomes, 2018; WHO, 2020), owing to a lack of respect for international humanitarian law (IHL), an increase in the number of international and non-international armed conflicts, the blurring of international boundaries and the use of aerial attack by unmanned aerial vehicles (commonly known as drones).

The type of negotiation undertaken in the field or at headquarters differs according to who is conducting it and at what level it takes place. Typically, negotiations are conducted by senior management staff based at headquarters elsewhere in the world, who are either professionally trained in negotiation skills or have a job description that demands this work as part of their role. In addition, local field staff are involved in day-to-day negotiations with community or regional leaders, state and non-state actors, and may or may not be aware that they are acting as part of their organisation’s wider mandate. Health diplomacy also involves negotiations with groups such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), the United Nations (UN) Cluster system, donor agencies, civil society organisations, foundations/trusts and corporations.

Negotiating access, especially in conflict settings, requires knowledge of the local and regional context and culture, the dynamics of various stakeholders and their influences in the region, and the affected population. Humanitarian organisations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and networks such as the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance (ALNAP) and the Humanitarian Practice Network have documented successes and failures by reflecting on their past attempts to negotiate humanitarian space (Magone et al., 2011).

While humanitarian interventions may not prevent attacks on hospitals, such as those in Kunduz in Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen, negotiations during complex conflicts can be used to mitigate or reduce such incidents in the future. In addition, humanitarian organisations may try to use quiet diplomacy and back-door negotiations to gain access; this has not been possible in complex situations such as those arising in the government-held regions of Syria and Yemen. Some aid agencies also use naming and shaming to denounce particular countries in order to gain access, but for various geopolitical reasons this method is rarely used.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) (2017) defines humanitarian diplomacy as “persuading decision makers and opinion leaders to act, at all times, in the interests of vulnerable people, and with full respect for fundamental humanitarian principles”. The term ‘humanitarian diplomacy’ has become fashionable among humanitarian organisations, but its meaning is often unclear owing to a lack of clear operational applications or of the impact of its use (Régnier, 2011; De Lauri, 2018). Mancini-Griffoli and Picot (2004, p. 12) report a comment from an experienced humanitarian worker: “We do nothing but negotiate, but are not always aware of it.” This shows that while the importance of negotiation is recognised, it is often not a formal part of an organisation’s culture or strategy. Minear and Smith (2007) have pointed out that humanitarian negotiators have to deal with potential conflicts between principles and interests as well as their own weak negotiating positions. An ICRC field practitioner has commented that “everything has to be negotiated by teams on the ground and it will always be painful and difficult” (Grace, 2014).

Gaining humanitarian access to affected populations in order to provide medical aid, protection and to maintain dignity is the fundamental duty of humanitarian organisations. To gain this access, negotiators at field level and at headquarters interact with state and non-state actors, going through various levels of negotiation or agreement depending on the nature and complexity of an individual situation. For a successful negotiation to take place, both humanitarian principles and the specific interests of involved parties need to be addressed and agreed upon. Often, the dilemma for humanitarian negotiators is whether they should make compromises for the sake of access or not. Each organisation has its own set of mandates and agendas that it applies when deciding whether to operate in a conflict situation. Methods of negotiation vary depending on an organisation’s size, political and religious ideology, availability of trained staff, sources of funding and leverage available with state or non-state actors. Additionally, in many contexts and regions, governmental and/or non-state actors do not respect or follow humanitarian principles, or IHL, while conducting negotiations for access. Either they do not understand the ethical and legal complexities of these principles or they think that these instruments are being used to control them. Both parties are aware of the interests at stake, and they have to find common interests.

Herrero (2014) describes the challenges of negotiations between the UN and the Syrian government: “Comfortable or not comfortable, we simply have to accept the situation, and live with some second best options […] we are caught between a rock and a hard place.” She ends her analysis of interests shared by state and non-state actors, their modi operandi and the approaches to negotiations thus:

The days when it was enough for humanitarian actors to simply invoke moral and legal obligations without referring to geostrategic and political considerations, if they ever existed, are long gone. While moral and legal arguments can still play an important role in negotiations, the expectations stemming from humanitarian actors´ leverage should be put into a more realistic perspective.

An analysis by Ratner (2011) describes the ICRC’s rationale for framing issues of legality in terms of interests, noting various situations in which ICRC delegates will not merely argue for compliance based on humanitarian, political, economic and pragmatic or moral grounds, but will rather refrain from invoking the IHL. Ratner (2011) further documents that invoking the language of interests is more useful than using IHL, and that the ICRC often avoids IHL arguments entirely. References to the use of IHL can become counterproductive and create resistance to future dialogue. In their Humanitarian Negotiations Revealed Report (Magone et al., 2011), MSF has documented the challenges faced by the organisation in gaining access to vulnerable populations, and the acceptable compromises with humanitarian principles that are necessary while negotiating with various state and non-state actors.

While international conflicts are becoming rare, there has been an increase in internal armed conflicts (Uppsala Conflict Data Program, 2018). In these situations, stakeholders are either legitimate states or non-state/semi-state entities, all of whom need to be engaged in dialogue during negotiations. In cases such as the attack on medical facilities by legitimate government forces in Kunduz, Afghanistan, negotiations occurred at international forums such as the UN Security Council to protect hospitals and patients and prevent further attacks on them (MSF, 2016; UNSC, 2016). As global health, foreign policy and politics are intertwined in either the provision of or denial of health care to a population in crisis, humanitarian organisations and their staff need to develop specific negotiation skills and the capacity to understand the complex interplay of power dynamics in this sector. The challenge for negotiators is to understand dilemmas in which they may have to make compromises with humanitarian principles that are usually considered non-negotiable, choosing the interests of both parties so that they can gain access – but without crossing any humanitarian red lines. To achieve this, they require a comprehensive understanding of the conflict, analysis of the stakeholders involved and the skills to engage with, and build long-term professional trust among, other parties, and persuade them to act.

Global health diplomacy

Global health diplomacy has been defined as “multi-level and multi-actor negotiation processes that shape and manage the global policy environment for health … the coal-face of global health governance — it is where the compromises are found and the agreements are reached, in multilateral venues, new alliances and in bilateral agreements’’ (Kickbusch et al., 2007). Kickbusch (2011) also notes that “health is an integral part of global agenda and foreign policy because of three global agendas, namely security, economic and social justice agendas”. Health is considered a security agenda owing to the emergence of pandemic diseases such as COVID-19, Ebola, H1N1, SARS and HIV, and an increase in natural disasters and conflicts. Developed and developing countries consider these issues to be national security issues that may affect their internal security owing to the import of a new disease or mass migration of population. Health is on the economic agenda owing to the economic impacts of pandemics and crises resulting in the poor health of the population and that these disasters and diseases give business opportunities for companies who provide services and products such as vaccines and medicines. Health is a social justice agenda, with the argument that health is a fundamental human right and that all populations need to have affordable and accessible health care to increase the chance of a healthy and safe life. Health is also an inherently political subject because it influences the well-being of an individual as well as the economic productivity and growth of a nation (Oliver, 2006).

Global health diplomacy has been used effectively to address issues such as negotiations concerning the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO, 2003), plain packaging for tobacco products (Intellectual Property Watch, 2018) and levying a sugar tax on sweetened beverages. Health diplomacy has also been involved in trade negotiations, vaccine negotiations and negotiations on access to medicine. However, current trends show that many developmental and humanitarian assistance programmes use health as a political tool to influence the objectives of global health. Health programmes such as fake polio vaccination campaigns in conflict regions (Lancet, 2014) to achieve foreign policy and political goals are unethical and unacceptable.

There are no accurate data on the effectiveness of the soft power of health diplomacy and negotiation, but it can be observed that better interactions between different stakeholders are beneficial (Kickbusch, 2011). The lessons learned from the implementation of health diplomacy in public health are transferable to the humanitarian sector.

Tools for humanitarian negotiations and diplomacy

Humanitarian negotiations take place between state and non-state actors in conflict situations, and can also be used effectively during other crises – natural disasters, pandemic outbreaks – and when negotiating access to affordable medicines through trade agreements. In 2017, the humanitarian sector employed approximately 570,000 personnel, according to the report ‘State of the Humanitarian System’ (ALNAP, 2018). Most of the staff are involved in negotiations at field and management level, interacting with local stakeholders, governments and armed non-state actors. The level of training and technical knowledge about negotiation techniques are not harmonised across field staff, management staff and international staff, although negotiations occur at all levels, each of which requires different skills.

The ICRC’s definition of humanitarian diplomacy is based on the committee’s mandate and is limited to the humanitarian sphere; it is independent of state humanitarian diplomacy (Haroroff-Tavel, 2005). Similarly, the IFRC adopted a humanitarian diplomacy policy in 2009, when a Governing Board (IFRC, 2017) focused on four signposts for action — the responsibility to persuade; persuading via appropriate diplomatic tools and actions; focusing on areas of knowledge and expertise; and engaging at appropriate times with external partners. Many small and medium organisations, however, may not have the capacity to create their own specific humanitarian diplomacy strategy or plan that allows them to formulate programme and training policies, so their staff can be equipped with the relevant negotiation skills.

During one of the panel discussions held at the first annual Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN) meeting, the lack of models and absence of best practices for negotiations that aimed to protect medical missions were identified. The same panel also stressed the need for the development of standard operating procedures, risk assessments, preventive measures and minimum standards to ensure the protection of medical missions (CCHN, 2016). There was a demand for negotiation tools and standard operating protocols that were specific to various humanitarian contexts.

A survey conducted by the CCHN showed that “frontline humanitarian negotiators were often left isolated and under-resourced and that they had to learn by doing, with limited contact with their peers”. It also showed that only a few of the respondents had any formal training in humanitarian negotiations (CCHN, 2017, p. 23). The availability of systematic tools to guide contextual differences would not only help with access to the population but also enhance negotiations to prevent attacks on medical infrastructure. The CCHN survey showed that there were two types of challenges to negotiations, internal and external (Table 1).

Table 1: Internal and external challenges to humanitarian negotiations

|

Internal challenges |

External challenges |

|

|

Modified from Final Report at Second Annual Meeting of Frontline Humanitarian Negotiators, 5–6 December 2017, page 23. (CCHN, 2017)

Negotiation capital is required to address these challenges. According to Benoliel (2017), there are four types – cognitive, emotional, social and cultural. There is an over-emphasis on cognitive capital in the capacity-building and training of professionals, ignoring the others, even though these are important traits. Humanitarian organisations need to create a negotiation ecosystem, which includes structures, processes and a support system for the negotiation team. Grace (2017) highlights the importance of capacity-building in humanitarian negotiations, and of a holistic approach towards development of all four types of capital, which are perceived as equally important.

A paediatric nurse checks a young girl for symptoms of diphtheria in the Kutupalong refugee camp, Bangladesh.

Photo: Russell Watkins/Department for International Development

Discussion

1. Theoretical and contextual knowledge

The humanitarian negotiator needs to acquire not only field knowledge about the context and conflict, but also theoretical and practical knowledge of negotiations and diplomacy. This knowledge and experience can be used in order to persuade decision-makers and opinion leaders to take action, so the population in need can be accessed. Negotiations happen at various levels and in different contexts. The negotiation team ideally comprises negotiators who have diverse technical and field experience, so they complement each other when planning and conducting negotiations. Carruth (2016) describes the process of health diplomacy at a medical clinic in the Somali region of Ethiopia, and concludes that:

the medical interventions at communities are shaped by local and interpersonal relations of power, distrust, and violence; the negotiations can either worsen the social conditions under which conflicts and crises recur or create spaces for trust and reconciliation … when diplomacy is practiced with this kind of sensitivity and explicit intentionally … peace can begin in the clinic.

Wilder (2008), in his analysis of the response to an earthquake in Pakistan, presents the importance of local cultural sensitivities and the motives of humanitarian organisations during the relief and reconstruction phases. For example, there were lengthy negotiations with local elders to allow Western women in the area to work with their heads covered, and he also shows how local cultural attitudes and practices that violate international human rights norms and laws were dealt with.

2. Risk of instrumentalising

Yves Daccrod, Director-General of the ICRC, describes the effect of a shift in the nature of conflict from civil war to proxy war in places such as Syria and Yemen: “the current diplomatic toolbox doesn’t work anymore”. He advocates for a diverse approach to allow for the varied nature of conflicts by adopting diversity in thinking, perspectives and opinions for negotiation teams (Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, 2018). This approach is useful in assessing the interests of individual actors, their intentions in keeping conflicts active and the approaches that the humanitarian agencies need to adopt to access the population. It may take many months, or even years, for these complex negotiation processes to build trust between the actors and local people. The negotiation team should be multidisciplinary, able to address the issues at local, regional and international levels. Neuman and Weissman (2016), discuss the challenges in negotiating with armed state actors and the UN Security Council:

What is more, we do not need new legal norms or mechanisms to condemn attacks against hospitals. The Security Council’s invitation looks more like a diversionary tactic that makes it possible to avoid addressing the urgent need to condemn the states responsible for attacks currently underway, including members of the Security Council and the diplomatic difficulties involved.

There is also a risk of instrumentalising humanitarian organisations, with either state or non-state actors utilising agencies for their own benefit, putting the affected population at risk. In these cases, a humanitarian negotiation strategy that provides a proper risk analysis of all the stakeholders will assist in making informed decisions.

3. Resource materials for humanitarian negotiations

The staff involved in negotiations need to be provided with appropriate training and mentoring within their organisation so they understand the complex issues and are able to design an appropriate negotiation strategy. This should ideally include training in core technical skills related to public health, water sanitation and similar subjects, as well as basic negotiation skills at the field level (Katz et al., 2011). Humanitarian and public health professionals may act without knowledge of larger diplomatic strategies while a humanitarian crisis is ongoing, but the long-term success of a project depends on the good will and trust that are built up between local populations and stakeholders (Katz et al., 2011). Therefore, training and capacity-building at field and management level are important in achieving effective humanitarian negotiation on the ground.

Various policy guidance documents and tools are currently used by humanitarian organisations to understand and learn negotiation skills. However, resource materials are often specific to a particular field, whether this be armed groups, protection or public health, for example (Table 2). Although useful in general terms, these resources are not suitable for planning systematic negotiations that require cross-disciplinary understanding and discussion, for example when talking about accessing health in humanitarian settings.

Table 2: Resource materials for humanitarian negotiations

|

Sources: Dragner et al. (2000); Mancini and Picot (2004); UNOCHA (2006).

One such systematic and useful resource is The CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation, which was developed by the CCHN, an entity established in October 2016 by five humanitarian organisations with the objective of facilitating the capture, analysis and sharing of humanitarian negotiation practices. In this field manual, the Naivasha Grid for planning and conducting negotiations provides a systematic framework for designing and conducting frontline negotiations by field practitioners, which can be adapted according to their contexts and needs.

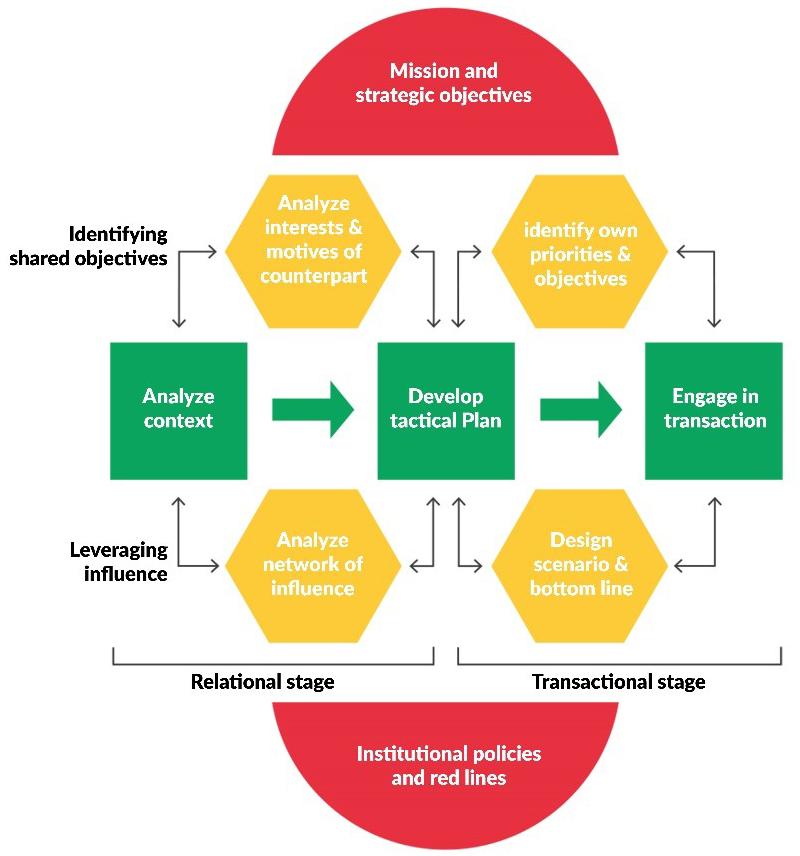

Figure 1: The Naivasha Grid

Source: CCHN (2018)

The Naivasha Grid helps with the analysis of context, stakeholder mapping, identifying priorities and objectives of an organisation and its opposite number, designing scenarios, designing tactics and defining red lines during all phases of negotiation. This tool can be adapted according to the context and type of negotiation – such as negotiating access to health care in regions affected by humanitarian disasters.

Conclusion

Humanitarian negotiation is multidimensional, multicultural and varies from region to region and culture to culture (Régnier, 2011). An effective humanitarian negotiator is one who can understand these challenges and learn to adapt and apply his/her skills and knowledge to persuade his/her counterpart to achieve the desired objectives. Negotiation skills and personal aptitude are important in building the knowledge and ability of a humanitarian negotiator. He/she needs to have a clear professional development plan, support from the organisation and mentoring opportunities, both inside the organisation and in the wider humanitarian sector.

Recommendations emerging from this study include: (1) documenting the processes and challenges of negotiations in conflict situations for a better understanding of stakeholders and their interests and needs, for future learning and to help adopt lessons learned; (2) advocating for an institutional culture that allows capacity-building of negotiation methods and skills (CCHN, 2016, p. 12); (3) investing in developing capacity by training medical, para-medical and other technical humanitarian professionals to conduct negotiations at field level and management level; (4) focusing on experiential learning and peer learning methods, soft skills and local cultural understanding to build good professional relationships with counterparts in the field and at higher levels of negotiation; (5) establishing a platform where best practices of negotiations from the field can be shared, with case studies from professional peers helping to build knowledge among humanitarian professionals; (6) developing context- and culture-specific tools of negotiation to allow access to health care for populations affected by conflict; and (7) advocating for investment in research relating to negotiations and conflict resolution among humanitarian and health organisations, the UN and donor agencies.

References

ALNAP (Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance). (2018). The State of the Humanitarian System. ALNAP Study. London: ALNAP/ODI. Available at https://sohs.alnap.org/help-library/the-state-of-the-humanitarian-system-2018-full-report [Accessed 14 December 2018].

Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. (2018). “Humanitarian Diplomacy” A conversation with Yves Daccord and Clare Dalton of the ICRC. [Seminar] Series: The Future of Diplomacy Project. Available at https://www.belfercenter.org/event/humanitarian-diplomacy-conversation-yves-daccord-and-clare-dalton-icrc [Accessed 21 December 2018].

Benoliel, M. (2017). Building negotiation capital. Asian Management Insights 4(1), 54-60. Available at https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/ami/67 [Accessed 21 December 2018].

Carruth L. (2016). Peace in the Clinic: Rethinking “Global Health Diplomacy” in the Somali Region of Ethiopia. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 40(2), 181–197. Available at http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11013-015-9455-6 [Accessed 19 December 2018].

CCHN (Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation). (2016). Annual Meeting of Frontline Humanitarian Negotiators. 25-26 October 2016. Available at https://frontline-negotiations.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Annual-Meeting-Report-2016.pdf [Accessed 19 December 2018].

CCHN (Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation). (2017). Second Annual Meeting of Frontline Humanitarian Negotiators. 5-6 December 2017, page 23. Available at https://frontline-negotiations.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Annual-Meeting-Report-2017.pdf [Accessed 19 December 2018].

CCHN (Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation). (2018). The CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation. Available at https://frontline-negotiations.org/home/resources/field-manual/digital-field-manual/ [Accessed 26 August 2021]

De Lauri, A. (2018). Humanitarian Diplomacy: A New Research Agenda. Available at https://www.cmi.no/publications/6536-humanitarian-diplomacy-a-new-research-agenda [Accessed 23 September 2021].

Drager, N., McClintock, E. and Moffitt M. (2000). Negotiating Health Development: A Guide for Practitioners. Conflict Management Group and World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, p89. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66659 [Accessed 19 December 2018].

Grace, R. (2014). Preparatory Review of Literature on Humanitarian Negotiation, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Harvard University.

Grace, R. (2017). The Humanitarian as Negotiator: Developing Capacity across the Sector. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available at https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3043968%20[Accessed 14 December 2018].

Harroff-Tavel, M. (2005) ‘The humanitarian diplomacy of the International Committee of the Red Cross’, January 2005. Available at http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/humanitarian-diplomacy-icrc.pdf (Accessed December 2018).

Herrero, S. (2014). Negotiating humanitarian access: Between a rock and a hard place. Available at https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/herrero-humanitariannegotiations_0.pdf [Accessed 14 December 2018].

Humanitarian Outcomes. (2018). Aid Worker Security Database. Available at https://aidworkersecurity.org/ Humanitarian Outcomes, USAID. [Accessed 18 December 2018].

ICRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Crescent Societies). (2015). Health care in Danger. Violent incidents affecting the delivery of health care. Available at https://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/publication/p4237-violent-incidents.htm [Accessed 01 September 2021].

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Crescent Societies). (2017). Humanitarian Diplomacy Policy. Available at https://www.ifrc.org/media/11944 [Accessed 23 September 2021].

Intellectual Property Watch. (2018). WTO Panel On Australia’s Tobacco Plain Packaging: A Fact Dependent Analysis Of TRIPS Art 20. Available at http://www.ip-watch.org/2018/07/03/wto-panel-australias-tobacco-plain-packaging-fact-dependent-analysis-trips-art-20/ [Accessed 14 December 2018].

Katz, R. et al. (2011) Defining health diplomacy: changing demands in the era of globalization. The Milbank Quarterly, 89(3): 503–523.

Kickbusch, I. (2011). Global health diplomacy: how foreign policy can influence health. British Medical Journal, 342(jun10 1), p.pp. d3154–d3154. Available at http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.d3154 [Accessed 19 December 2018].

Kickbusch, I. et al. (2007). Global health diplomacy: the need for new perspectives, strategic approaches and skills in global health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, March 85, p.pp. 230–232. Available at https://scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862007000300018&lng=en&tlng=en [Accessed 20 December 2018].

Lancet, T. (2014). Polio eradication: The CIA and their unintended victims. The Lancet, 383(9932), 1862. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60900-4

Magone, C., Neuman, M. and Weissman, F. [eds] (2011). Humanitarian Negotiations Revealed: The MSF Experience. Médecins Sans Frontières. London: Hurst & Co.

Mancini-Griffoli, D. and Picot, A. (2004). Humanitarian Negotiation – A Handbook for Securing Access, Assistance, and Protection for Civilians in Armed Conflict”. Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. Available at http://www.hdcentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Humanitarian-Negotiationn-A-handbook-October-2004.pdf [Accessed 09 December 2018]

Minear, L. and Smith, H. [eds] (2007). Humanitarian Diplomacy: Practitioners and Their Craft. Tokyo and New York: United Nations University Press.

MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières). (2018). “No One Was Left”: Death and Violence against the Rohingya in Rakhine State, Myanmar. Médecins Sans Frontières https://www.doctorswithoutborders.ca/sites/default/files/2018_-_03_-_no_one_was_left_-_advocacy_briefing_on_mortality_surveys.pdf

MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières). (2016). MSF President to UN Security Council: “Stop these attacks.” [Speech] Médecins Sans Frontières International Available at https://www.msf.org/msf-president-un-security-council-stop-these-attacks [Accessed 20 December 2018].

Neuman, M. and Weissman, F. (2016). Humanitarian diplomacy, a fig leaf for extreme violence. 27 September 2016. Available at https://www.msf-crash.org/en/blog/war-and-humanitarianism/humanitarian diplomacy-fig-leaf-extreme-violence. [Accessed 21 December 2018].

Nonprofit Quarterly. (2017). When Your Medical Infrastructure Is Destroyed: Report from Syria. Available at https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2017/03/17/medical-infrastructure-destroyed-report-syria/ [Accessed September 26, 2018]

Oliver T. R. (2006). The politics of public health policy. Annual review of public health, 27, p195–233. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123126

Ratner, S.R. (2011). Law Promotion Beyond Law Talk: The Red Cross, Persuasion, and the Laws of War. European Journal of International Law, 1 May 22(2): 459–506. Available at https://academic.oup.com/ejil/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/ejil/chr025 [Accessed 14 December 2018].

Régnier, P. (2011). The emerging concept of humanitarian diplomacy: identification of a community of practice and prospects for international recognition. International Review of the Red Cross, December 93(884): 1211–1237. Available at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1816383112000574 [Accessed 14 December 2018].

UN (United Nations). (2018). Rohingya refugees face immense health needs; UN scales up support ahead of monsoon season https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/02/1003122 [Accessed 12 December 2018].

UNHCR. (2004). Protracted Refugee Situations. Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme, Standing Committee, 30th Meeting, UN Doc. EC/54/SC/CRP.14, 10 June 2004, p. 2

UNOCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). (2006). Humanitarian Negotiations with Armed Groups - A Manual for Practitioners by UNOCHA. Available at https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/HumanitarianNegotiationswArmedGroupsManual.pdf [Accessed 12 December 2018].

UNOCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). (2018). UNOCHA - Appeals, Available at: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2018. [Accessed 23 August 2021].

UNSC (United Nations Security Council). (2016). Security Council Adopts Resolution 2286 (2016), Strongly Condemning Attacks against Medical Facilities, Personnel in Conflict Situations, Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. Available at https://www.un.org/press/en/2016/sc12347.doc.htm [Accessed 20 December 2018].

UNSC (United Nations Security Council). (2018). SC/14612. https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sc14612.doc.htm [Accessed 23 August 2021].

Uppsala Conflict Data Program. (2018). Department of Peace and Conflict Research- Uppsala University, Sweden. Available at http://www.uu.se/en [Accessed 20 December 2018].

WHO (World Health Organization). (2003). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organisation. Geneva. Available at https://fctc.who.int/publications/i/item/9241591013 [Accessed 14 December 2018]

WHO. (2020). Attacks on Health Care: Three-Year Analysis of SSA Data (2018-2020). https://www.who.int/data/stories/attacks-on-health-care-three-year-analysis-of-ssa-data-(2018-2020) [Accessed 22 Sept. 2021].

Wilder, A. (2008). Perceptions of the Pakistan Earthquake Response https://fic.tufts.edu/assets/HA2015-Pakistan-Earthquake-Response.pdf [Accessed 14 December 2018].

![Engasjert antropologi i turbulente tider [Engaged Anthropology in Turbulent Times].](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/19475-Screenshot-2025-12-25-at-180604.png)

![Å holde flammen tent: Engasjert antropologi i mørke tider [Tending the flame: Engaged anthropology in dark times]](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/19474-Screenshot-2025-12-25-at-175845.png)

![Ti år med flyktningkriser og folkerettsbrudd i Europa (2015–2025): Kunne EU og Norge ha svart annerledes? [A Decade of Refugee Crises and Violations of International Law in Europe (2015-2025) – Could the EU and Norway Have Responded Differently?]](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/19473-Screenshot-2025-12-25-at-173706.png)