Before going for fieldwork to the Tibetan settlements in South Karnataka, after a long gap of two years, everything felt different this time. The unprecedented Covid-19 pandemic has changed life in complex ways. More than excitement, my mind was filled with anxieties. The late-night Kaveri Express train from Chennai Central reached Mysuru early next morning. The graffiti artwork in the subway leading to the railway station entrance reminded me that the journey had begun. My eight-day fieldwork (October 23-30) in three Tibetan settlements – Dhondenling, Lugsum Samdupling and Rabgyeling – started with pouring rains in Mysore.

It was my first visit to Dhondenling Tibetan Settlement, located near Odeyarapalya village in Kollegal taluk of Chamarajanagar district. According to the CTA website, the settlement was established in 1974 and had a total area of 3000 acres. Like the other Tibetan settlements in Karnataka, Mysore Resettlement and Development Agency (MYRADA) was part of setting up Dhondenling in the initial stages along with GoI and the Karnataka State Government. At present, CTA appoints a Settlement Officer to look after the administrative affairs who works with the elected Camp Leaders of twenty-two villages. Like Rabgyeling Settlement near Gurupura in Hunsur, the villages are named alphabetically, and it is a predominantly agriculture-based settlement. The Biligiriranga Hills (B.R Hills), surrounding the vast agricultural fields, and the pleasant greenery combined with refreshing weather, at the height of above 3000 ft from sea level, is naturally appealing like many other villages in the Western Ghats region. The place is popularly known as ‘Mini Swiss’ among the Tibetan community.

After writing down the field notes for the first day, I opened Old Demons, New Deities late in the night to read. It is an anthology of short stories featuring works of Tibetan writers, including Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, Bhuchung D Sonam, Jamyang Norbu, Tenzin Tsundue, Tsering Woeser, Pema Tseden and others. In the compelling introduction, Tenzin Dickie, Tibetan writer and literary translator who edited the book, wrote something thought-provoking, which stayed with me throughout the fieldwork days and beyond. Recollecting the memory of watching a Tibetan film for the first time in her life, Dickie quotes Junot Diaz and writes,

“… I finally realized with a jolt what I was watching: this was a Tibetan film, a Tibetan romantic comedy. I had never seen a Tibetan film before. There were none. There were no Tibetan films, no Tibetan short stories, no Tibetan novels. Junot Diaz says, “You know how vampires have no reflections in the mirror? If you want to make a human being a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves.” We grew up, those of us who grew up in exile but also those of us who grew up in Tibet, all of us, without reflections.”

Reflections, in this context, is a powerful word. It challenges many pre-conceived notions about the history and lived realities of the Tibetan exile community. More importantly, it conveys how little we had listened and understood and shows the long-distance of learning ahead. How does contemporary Tibetan cinema or the realm of visual self-representation depicts and documents the diverse experiences, memories and histories of Tibetans? How does it ‘reflect’ the experiential realities of the community and their struggles? How many stories are left untold? How can the world of images, lights and sounds capture people’s intricate experiences without a reductive lens of displacement or alienation? Why is the denial of ‘reflections’ political? These questions occupied my thoughts.

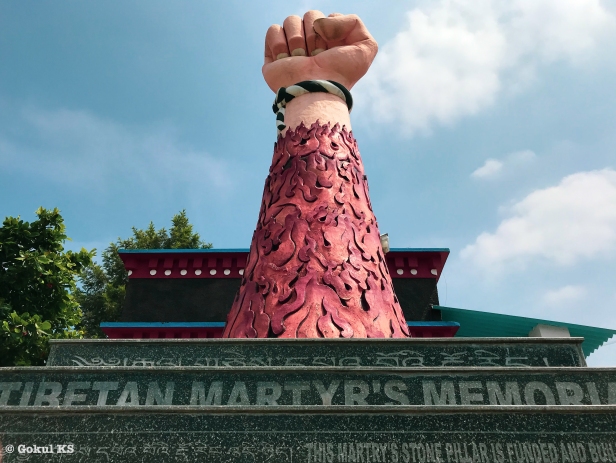

Human settlements and landscapes, beyond their geographical features, reflect past and present in unsaid ways. Paying close attention to those stories and observing the space matters in fieldwork. Tibetan settlements in Karnataka were built from scratch in the early decades of exile. As documented in many oral, visual and historical accounts, people escaping the PRC oppression in Tibet have come to different parts of the Himalayan region since 1959 searching for freedom and peace. Many elderly Tibetans recollected their early days in exile during our conversations. Some of them were part of the labour force behind the construction of high-altitude roads in Kullu-Manali. After the establishment of the settlement in the mid-1970s, many Tibetans were resettled in Dhondenling. The climatic conditions and environment were diametrically distinct from the Himalayan regions and Tibet. The people who talked to us about their early days in the settlement shared the stories of struggles and hardships. The history of Tibetan settlements is also about, among other things, the long journey of resilience and everyday negotiations with the experiential realities in exile. We also listened to the personal experiences of the ex-army men who were part of the Special Frontier Force (SFF) during the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence and the 1999 India-Pakistan armed conflict in Kargil.

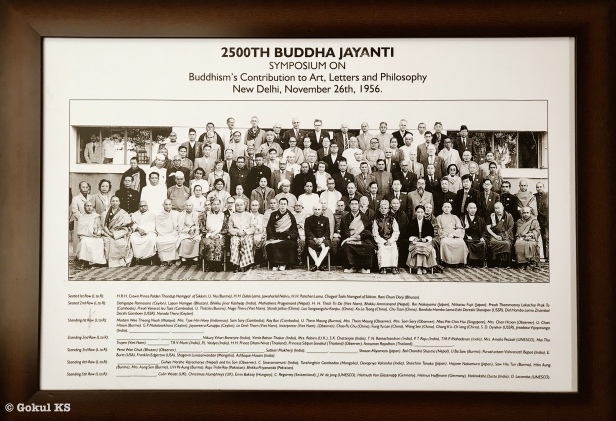

After listening to the personal/collective recollections, while processing and attempting to make sense of the specificities of diverse experiences, I could not help connecting the re-membering aspect of many of the conversations with what Dickie calls “reflections”. Tibetan and non-Tibetan filmmakers have made several films and documentaries to preserve these recollections over the last few decades. On the other hand, my research journey has been a travel to the location of the filmmaking process where these visual productions take shape and gain aesthetic, thereby political, momentum. During this week-long fieldwork, I interacted with filmmakers, visual artists and musicians, including Tenzin Choegyal, Gyurme Tenzin, Karma Yeshi Namdok, and Tenzin Choku, who, through their works, reflected on the lived realities that surround them. It constitutes everything, ranging from the small moments of joy in everyday life to harrowing memories of the journey into exile and the ongoing political struggle for self-determination. The images, music, lights, colours and rhythm carried many emotional layers. In our conversations, the thought process behind those cultural productions took precedence over the text, and we unpacked some of those layers. I realized that these interactions are also a process of chasing different aspects of the past that inform the present.

After spending four unforgettable days and nights in Dhondenling, the next stop was the Lugsum Samdupling Tibetan settlement near Bylakuppe in the Mysore district. Two years ago, in August 2019, my research on Tibetan cinema and filmmaking started with fieldwork to the same settlement. It is the first Tibetan settlement in India, established in the year 1961. The neighbouring Dickey Larsoe Settlement came at the end of the decade in 1969. We also spent a day in Rabgyeling Tibetan Settlement, located near Gurupura village in Hunsur taluk of Mysore district, established in 1971. Going back to a settlement where you have already been and have some relationship with people is a memorable experience. You will always have conversations to look forward to and places to revisit. The pandemic has affected the livelihoods of many Tibetans – including farmers, traders, shop owners and people engaged in sweater business – in these settlements in Bylakuppe. The architectural marvel of monasteries within the settlement – including the Namdroling, Sakya, Sera and Tashi Lhunpo monasteries – attract many international and local tourists. It is also known for Tibetan thangka paintings, handicrafts, souvenirs and restaurants serving Tibetan food.

Vast agricultural lands, clearly demarcated villages, architecturally imposing monasteries, and the unique flavours of Tibetan cuisine are some of the features of Tibetan settlements in Karnataka that frame the visual images about that space in our minds. I hope these images, in non-linear order, narrate a story of their own, similar to the spaces within its frames. Even though images freeze a moment and capture a particular view (inherently/simultaneously excluding others), they can be interpreted differently. This feature or possibility of photography consciously guides the choices I often have made in the field. More than the people, my attention is on what surrounds them. The settlement spaces are reflections of the communities that embraced them. It can speak volumes about the formation and evolution of, in this context, the Tibetan community in exile. Images, moving and still, cannot capture these reflections in their entirety. Nevertheless, they preserve some of them. I can see people in these images – the people with whom I travelled and spent time, the ones who shared many memories, brief encounters, deep conversations, those who smiled and waved, and the imaginary people I visualized in my mind when I heard stories about the times past.

On the last night of the fieldwork, I opened another book, gifted by respected Thubten Samphel la, when I met him this time at Tibet Kitchen for dinner. Tibet: Reports from Exile, published by Blackneck Books, is a collection of articles and essays written by Thubten Samphel for four decades on various aspects of Tibetan history, culture, politics, exile and society. The first piece in the book is an article titled “Impressions from Tibet”, published by Tibetan Review in December 1985. It is a detailed personal ‘recollection’ of his journey to Tibet as part of the Fourth Fact-Finding Delegation sent by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. One striking part of the article, three and a half decades later, is sadly a reality in Tibet (and beyond). He writes,

“… unlike in an open society where facts speak for themselves, in Tibet it is the officials who speak for the facts. They can even juggle the facts to produce a variety of conflicting ‘truths’. Truth is a matter of opinion whereas facts are sacred and in Tibet they can even be scarce.”

‘Reflections’ and ‘recollections’ are subjective truths, and it is a never-ending negotiation process with evolving conditions. The journey continues…

The author is a PhD Candidate at IIT Madras researching on ‘Tibetan cinema and filmmaking’ and co-curator of Tibetscapes

![Engasjert antropologi i turbulente tider [Engaged Anthropology in Turbulent Times].](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/19475-Screenshot-2025-12-25-at-180604.png)

![Å holde flammen tent: Engasjert antropologi i mørke tider [Tending the flame: Engaged anthropology in dark times]](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/19474-Screenshot-2025-12-25-at-175845.png)

![Ti år med flyktningkriser og folkerettsbrudd i Europa (2015–2025): Kunne EU og Norge ha svart annerledes? [A Decade of Refugee Crises and Violations of International Law in Europe (2015-2025) – Could the EU and Norway Have Responded Differently?]](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/19473-Screenshot-2025-12-25-at-173706.png)