Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus after the Second Karabakh War. Prospect for Regional Cooperation and/or Rivalry

The Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus

Changed dynamics after the Second Karabakh War

The geopolitical impact of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

National Perspectives on the Changing Geopolitics

Challenges/constraints and opportunities for regional cooperation

Armenia as an actor in the South Caucasus region

Conclusion: An Armenian perspective

Azerbaijani perspectives on the geopolitical situation

Opportunities and potential for regional cooperation

Georgian views on the changing geopolitics of the South Caucasus

Georgian elites’ perceptions of the changing geopolitical climate

Assessing the potential for regional cooperation

Elite perceptions and Russia’s role in the region

Scenarios for the future of the Caucasus

Turkish positions in the changing geopolitics of the South Caucasus

Observations of the social and geopolitical context after the Second Karabakh War

Overview of the bilateral relations between Azerbaijan and Turkey

Discourses and perspectives on regional cooperation

The Role(s) of External Actors

How to cite this publication:

Siri Neset, Mustafa Aydin, Ayça Ergun, Richard Giragosian, Kornely Kakachia, Arne Strand (2023). Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus after the Second Karabakh War. Prospect for Regional Cooperation and/or Rivalry. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report 2023:4)

This report is from the research project “Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus: The Prospect for Regional Cooperation and the Role of the External Actors”, funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The report covers the period July 2021–June 2022 and presents an overarching analysis of the geopolitical changes in the aftermath of the second Karabakh War. The report further provides accounts and perspectives on conflicts, regional collaboration and trade in South Caucasus as seen from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. Additionally, the effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the initial impact of this war on the region is analyzed. The report concludes with an epilogue presenting updated reflections on the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the South Caucasus and recent initiatives for peace negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

This report is from the research project “Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus: The Prospect for Regional Cooperation and the Role of the External Actors”, funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The report covers the period July 2021–June 2022 and presents an overarching analysis of the geopolitical changes in the aftermath of the second Karabakh War. The report further provides accounts and perspectives on conflicts, regional collaboration and trade in South Caucasus as seen from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. Additionally, the effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the initial impact of this war on the region is analyzed. The report concludes with an epilogue presenting updated reflections on the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the South Caucasus and recent initiatives for peace negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The report and the project were executed through a collaborative effort by researchers from the South Caucasus, Turkey, and Norway, headed by Siri Neset. Throughout the project duration continuous desk-based research was undertaken. The project started off by a series of webinar group interviews with researchers working on relevant areas in relation to the region and with researchers working on institutional ties with the region (i.e. NATO, EU, OSCE) to pinpoint key variables and drivers. Thereafter, an interview protocol was developed, and the team conducted semi-structured expert interviews in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey as well as informal conversations with political elites. These strands of data were processed through a category-based analysis.

Executive Summary

This report presents the different country perspectives, main findings, and an updated epilogue from the research project “Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus: The Prospect for Regional Cooperation and the Role of the External Actors”, funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Throughout the project period between July 2021 and June 2022, the region continued to evolve with a stream of fast-changing developments in the countries and how it is perceived globally. The Russian invasion of Ukraine severely shook the region, and the possible long-term consequences for Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and external actors are somewhat unclear.

The 45-day war over Nagorno Karabakh in 2020 changed the geopolitical landscape dramatically. With Azerbaijan`s victory, new borders were drawn in the region. The regional balance of power also shifted, and the potential for regional cooperation increased while the role of external actors changed. Azerbaijan gained political and military dominance, Armenia`s power and influence dramatically decreased, and Georgia found itself in danger of being sidelined should Azerbaijan and Armenia manage to sign a peace agreement. Russia was the broker of the ceasefire agreement and increased the presence of military peacekeepers, and Turkey had a robust political comeback to the region and military presence in Azerbaijan. The new situation has set the stage for opening the region and increasing regional and international connectivity through new or re-opening transport corridors, railways, and energy transportation projects. Trade and transport are the most likely areas of cooperation between the regional countries and may proceed in tandem with, or independent of, the peace process between Azerbaijan and Armenia. The war and the Russian-brokered truce marked a significant blow to European and U.S. initiatives to solve the conflict through the OSCE Minsk Group format. And while the West stressed its readiness to contribute, the various actors needed more credibility to deal with hard security issues in the region.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the regional situation has become even more fragile, adding new risks to an unstable security environment. Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan have initially tried to connect with the Western block while also attempting to avoid drawing any attention from Russia. The long history of conflicts in the region and Russian dominance means there are serious concerns within all the countries that Russian influence may now increase. Still, there is also the possibility that the trembles of Russian actions in Ukraine and changes in the international order might change the historical patterns of behaviour that, in a best-case scenario, might lead to regional unification against a common threat. All countries might see a need to reduce the consequences of Russian pressure and protect their national sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence.

The war in Ukraine may catalyse the peace talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The E.U. , and more recently the U.S., has stepped in as a facilitator to the bilateral process that is perceived to make real progress. There is cautious optimism but also concern about how Russia will act. In general, the room for manoeuvring by external actors has increased. There is an awareness about a change in the regional power balance between Russia and Turkey, amongst the regional powers, and vis a vis external power. Turkey could increase its standing in the region and become a challenge to Russian dominance. However, this would necessitate a reshaping of its Russian policy. Under the current circumstances, the regional countries would no doubt benefit from a suitable platform to discuss the current situation and possible futures with external powers.

The Changing Geopolitics of the South Caucasus

Background

Mustafa Aydın

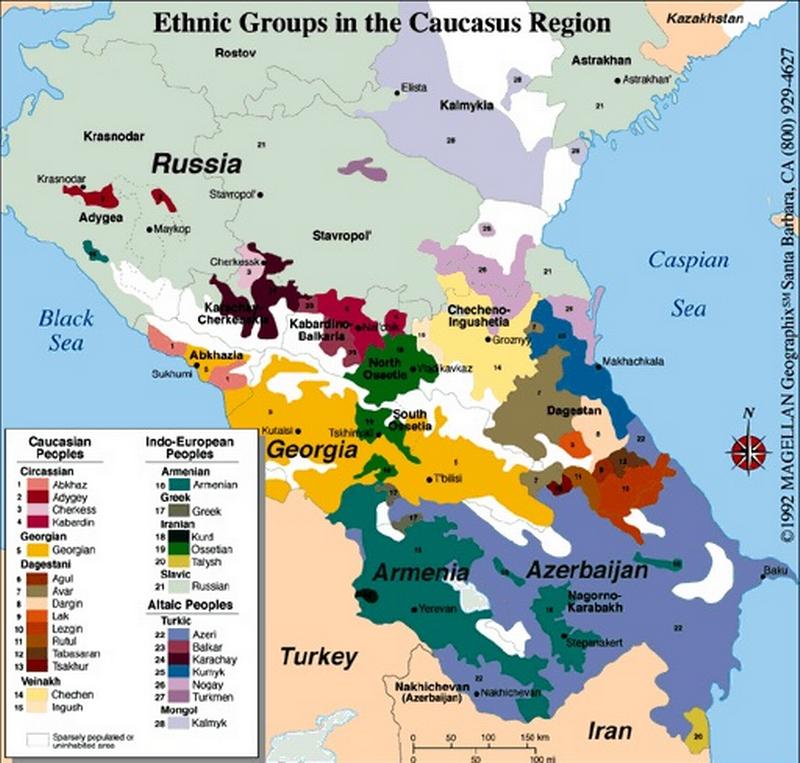

Before the establishment of the Soviet Union, the Caucasus was an area of competition between the Ottoman, Persian, and Russian empires, resulting in a blending of cultures along vital transit routes. The ensuing competition included religious, ethnic, and imperialistic overtures. Regional peoples were forced to migrate several times depending on their religion and/or political allegiance.

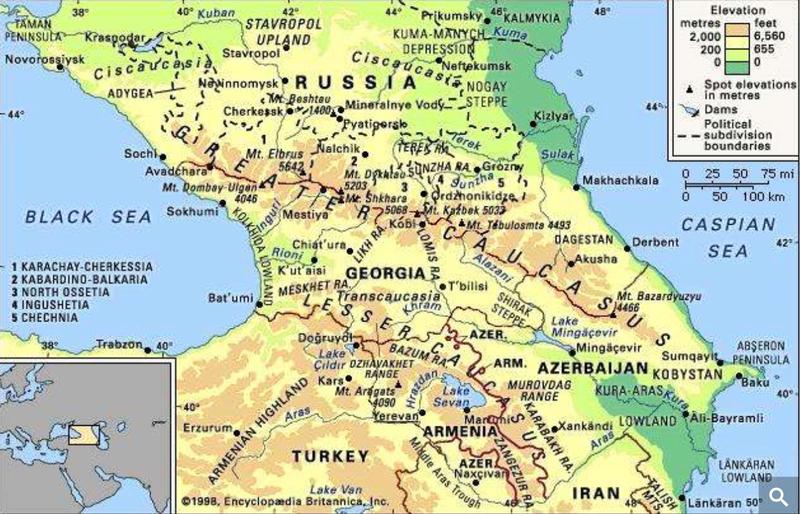

The Caucasus lies between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea and comprises Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia – although parts of Russia, Turkey, and Iran could also be included geographically. The Caucasus Mountains, where Europe and Asia converge, separate the North Caucasus, part of Russia, and the South Caucasus of the three independent Caucasian countries. From a Russian perspective, the latter was called Trans-Caucasus (Zakavkáz’je in Russian) in history, meaning the region “beyond the Caucasus Mountains”. The Greater Caucasus watershed is traditionally considered the dividing point between Europe and Asia. Consequently, while some analysts put the western portion of the Caucasus region in Europe and the eastern part (the majority of Azerbaijan and small parts of Armenia, Georgia, and Russia’s Caspian Sea coast) in Asia, others identify the Aras River as the border of Turkey as the continental demarcation line that presents Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia in Europe.

The history of the Caucasus is a history of centuries of constant movement across the region. The region geo-strategically lays along the roads connecting the north to south and east to west. Leaving aside the region’s earlier history, the northern part of the Caucasus has been defined by its resistance against Russian attacks and attempts to subdue its people since the early 19th century. The southern part also witnessed foreign invasions and power struggles among the Russian, Ottoman, and Persian states until the end of the First World War. Finally, the Soviet Union consolidated its control north and south of the Caucasus Mountains. Along the way, however, following the 1917 Revolution and the withdrawal of the Russian forces from the region, the South Caucasian people were able to unify into a single political entity as the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic between 9 April 1918 to 26 May 1918 and later as the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic from 12 March 1922 to 5 December 1936. Subsequently, however, they were incorporated into the Soviet Union.

During the Second World War, the Northern Caucasus witnessed intense clashes between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and German forces occupied significant parts. Nazi Germany withdrew from the region after the Battle of Stalingrad (1942-1943). Still, the cooperation between some local people and the Nazi troops led to the forceful removal of various ethnic groups from the region by the Stalinist regime.

Map 1: The Caucasus, physical. Source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Caucasus

During the rest of the 20th century, the Soviet Union closed the region to outside connections and influence. The South Caucasus formed one of the border zones between the Soviet Union and the Western Alliance. There was watchful suspense across the region as neither side could make any military or strategic move without risking nuclear war.

The Soviet Union’s direct control of the South Caucasus ended with the Union’s collapse in December 1991, and Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia were finally independent countries. However, the North Caucasus remains part of the Russian Federation, and various territorial disputes have since emerged, allowing Russia to exert its influence over the region. In the South Caucasus, the fall of the Soviet Union brought forth sources of tension and grievances that the Cold War suppressed. There was also an increased possibility that the West would move into former Soviet-controlled areas through partnerships and cooperation programs. However, the competition for influence over the region again rose in the post-cold war era between Russia, Turkey, and Iran. These tensions formed the background for the successive territorial, nationalistic, ethnic, and partly religious disputes across the region.

The changes in international relations since 1989 have significantly altered the political geography of Eurasia, putting the newly independent states into global calculations. The sudden emergence of the Caucasian (and Central Asian) states caught the local populations and the world unprepared. During most of the twentieth century, strategists and geopolitical experts considered these lands the Soviet Union’s hinterland. On the other hand, the U.S. tried to “contain” these areas by linking its various alignment systems. Thus, Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan became important outposts of this policy. However, the collapse of the Soviet Union changed this dramatically, putting the newly independent states firmly into global geopolitical calculations. This is because it was discovered that they have essential natural resources (i.e., Azerbaijan), sat across important transit routes (i.e., Georgia), or were engulfed in various conflicts (all three Caucasian countries). Where Russia’s power and influence weakened, the newly independent states have taken different roads toward national consolidation, economic development, and political alliances. This brought about international security and policy issues that did not exist before the fall of Soviet power. It soon became apparent that, besides the Russian Federation, the area constituted a matter of profound interest and vital concern for Turkey, Iran, China, the U.S., and the E.U.

While national minorities rediscovered long-suppressed identities and demanded new rights throughout the region, political leaders in all the countries plunged into what could best be described as a prolonged period of nation and state-building. Most of the region’s economy, logistical, and communication infrastructures were centralised during the Soviet period. Therefore, when the Union dissolved, the individual countries became independent and cut off from economic and financial connections, creating significant obstacles to national development.

The newly independent countries have dealt with the post-Soviet transition in different ways, which has resulted in varying levels of conflict. Most of the earlier post-Soviet leaders in the Caucasus discarded the Soviet political tradition and the legacy of the old regime. Instead, they tried to replace the old system with new power bases and institutions. However, their challenges to the previous political order resulted in several violent clashes, uprisings, and, in some cases, civil war. Even in cases where violent conflicts were avoided, several dynamics, including ethnic differences, religious diversities, economic problems, environmental issues, and external influences, have caused instability.

Table 1: Basic characteristics of the Caucasian countries

|

|

Azerbaijan |

Armenia |

Georgia |

|

Capital |

Baku |

Yerevan |

Tbilisi |

|

Area (km2) |

86,600 |

29,743 |

69,700 |

|

Population |

10,009,595 |

2,936,526 |

3,904,824 |

|

Governing System |

Semi- presidential republic |

Parliamentary system |

Semi-presidential representative democracy |

|

Current Leadership |

Ilham Aliyev (President) Ali Asadov (PM) |

Armen Sarkissian (President) Nikol Vovayi Pashinyan (PM) |

Salome Zourabichvili (President) Irakli Garibashvili (PM) |

|

Ethnic Groups* |

Azerbaijani (91%), Lezgi (2%), Armenian (1.3%), Russian (1.3%), Tallish (1.2%), Avar (0.5 %), Turkish (0.4%), Tatar (0.3%), Tat (0.3%), Ukrainian (0.25%) |

Armenian (98%), Yazidi, Russian |

Georgians (86,6 %), Russian (0,7%), Jew, Azerbaijani (6,3%), Armenian (4,5%), Ossetian (0,4%), Yezidi, Greek, Ukrainian, Laz |

|

Religious Groups |

95% Muslim |

Armenian Apostolic Church (93%), Sunni Islam |

Orthodox Christianity (83,4%), Armenian Christian (2,9%), Muslim (10,7%), Roman Catholic (0.8%) |

|

GDP Growth Rate |

5,6 % |

5,7 % |

10,4 % |

|

Life Expectancy |

73.1 years (70.3 years for males, 75.7 years for females) |

74.9 years (71.6 years for males, 78.5 years for females) |

72.6 years (68.3 years for males, 76.8 years for females) |

* Figures for Georgia are according to the 2014 census, excluding Abkhazians and Ossetians living in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Ethnic Georgians comprise three groups: Kartvelian, Mingrelian, and Swan.

During the Soviet era, the central government tried to suppress any distinction that challenged the supremacy of communist ideology, including national identities. However, ethnic minorities in all republics were recognised and written at the ethnicity line of their I.D. cards. The borders of the union republics did not aim to create homogeneous republics or confirm historic quasi-identities. Instead, they divided people and endeavoured to replace them with identities flowing across officially recognised republic borders.

The attempted nationality engineering under the Soviet regime included a mixture of local, tribal, and ethnic groups and identities in each country. While strict totalitarian rule and suppression kept the destabilising character of ethnic and religious diversity under control during the Soviet era, the root causes of instability remained, leading the region into turmoil after the collapse.

Each of the Caucasian states has a dominant titular nationality alongside many minorities (see map two and table one for more details). Moreover, the region has a complex diversification of religious faiths closely related to separate national-ethnic identities. The Azerbaijanis belong to the Turkic ethnicity, most of whom are Shi’ite Muslims. Most Armenians and Georgians are followers of two branches of the Eastern Orthodox Church. The affiliations of national churches interact with national identities in Georgia and Armenia. Azerbaijan has been concerned about possible Iranian influences as most of its population are Shiite Muslims. Finally, there are Armenians living in Azerbaijan and Georgia. While the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region is located within the borders of Azerbaijan, and most of its population was Armenian at the time of the independence. In contrast, the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic, part of Azerbaijan but located between Armenia and Iran, is populated primarily by Azerbaijanis.

The geopolitics of the South Caucasus in the post-Cold War era have constantly evolved, mainly to the interests of nearby regional countries (Russia, Turkey, Iran) and global powers (the U.S., the E.U., and individual European countries such as France). During the 1990s, the leading outside players were Russia, Turkey, and Iran, the latter of which played for more cultural and semi-political influence with economic undertones. At the same time, Turkey and Russia were locked in intense competition with political, ethnic, economic, energy, security, and religious dimensions. Turkey received support from the West, especially the U.S., as a conduit with the regional countries in this competition. Turkey’s offer to link the region to Europe with energy pipelines, road-rail connections, and political, military, and economic advisory and support roles is attractive to the regional countries. Nevertheless, they felt constrained by the existence of Russian soldiers in their territories – a legacy of Soviet-era agreements with various military bases. Further, there was an increased emergence of ethnic/national conflicts, with Russia as a player.

In this aspect, the emergence of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict even predates the demise of the Soviet Union. Armenians and Azerbaijanis had remained in a state of tense watchfulness towards each other during most of the 20th century as their versions of national histories clashed over most of the modern territories of Azerbaijan and Armenia. With plenty of examples of grievances on both sides to cite, only the Soviet heavy hand kept them from outright conflict, although occasional local clashes did break out. What started yet another clash between the two countries over the demands of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic to join the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1987 turned into a full-scale war by the end of 1991 when both Azerbaijan and Armenia declared their independence. The Azerbaijan SSR parliament abolished the oblast’s autonomous status on 26 November 1991, before it declared independence. In turn, the Armenian population of the oblast declared their independence, which was immediately supported, though not recognised, by Armenia. The ensuing conflict saw Armenian forces capture the whole territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and, quickly, seven raions (regions) around it, amounting to 20 % of Azerbaijan’s territory. The ceasefire reached in 1994 provided a degree of fragile stability due to the lack of a negotiated resolution to the conflict. Finally, Azerbaijan regained control of the occupied rayons and some of the territories of the former autonomous oblast during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Meanwhile, Georgia has been engulfed in not one but three ethnic disputes in its territory since its independence. The heavy-handed Georgian nationalist rhetoric of the Gamsakhurdia regime in the early 1990s could be blamed for the emergence of resistance among the Acara, Ossetian and Abkhazian minorities of the country. However, their geographical location could explain Abkhazia’s descent into civil war with the central government while Acara found a way forward. Acara sits on the border with Turkey, which did not encourage its secession. Abkhazia and South Ossetia are straddled along the border with Russia, which has not missed an opportunity to get involved. Critical in this aspect was the decision of the Saakashvili government in the early 2000s to move towards NATO membership, which irked Russia even further. In the end, a brief war between Russia and Georgia in August 2008 saw the effective declaration of independence by Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which is recognised by only a handful of countries and Russia, while most of the international community recognises the territorial integrity of Georgia.

The August 2008 Georgia-Russia War affected regional geopolitics immensely as the regional countries realised the length Russia would go over its presumed interests in the region and the inability of other players to prevent such an outcome. Moreover, the withdrawal of the U.S. from the area, which had shown growing military/security interests after the 9/11 attacks, also played a role. Finally, Turkey reorientated its foreign policy towards the Middle East in the early 2000s after securing the establishment of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) pipelines. The calculation that cooperation with Russia over various neighbouring geographies would yield better results than competing with it was equally important in this outcome. Similarly, the E.U.’s internal problems and declining interest in the region after sharing the region’s energy resources was accomplished were instrumental in increasing the influence of the Russian Federation, which had developed its relations with Azerbaijan and expanded its hold over Armenia.

Changed dynamics after the Second Karabakh War

Siri Neset and Mustafa Aydın

The Second Karabakh War again showed that the region’s geopolitics have continued to evolve. This time we have witnessed a comeback from Turkey; the marginalisation of Iran; the further weakening of the role of the West, including the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE); and the emergence of a Russian-Turkish partnership and competition for the future of the South Caucasus. More recently, the Russian attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 yet again dramatically and instantly altered the already delicate geopolitical landscape. As it is seen as the Russian leadership’s resentment of any degree of “sovereign choice” among its neighbours, it is perceived as a grave security problem for the South Caucasian states, too.

The 44-day war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh and the occupied territories of Azerbaijan from 27 September to 9 November 2020 culminated in a protracted conflict over the region since the end of the Cold War and the independence of these Caucasian states. The war ended with a ceasefire agreement on 9 November 2020, with Russian mediation, though no peace treaty has yet been signed.

The war marked a dramatic shift in the balance of power in the region. While Azerbaijan now clearly dominates the political and military scene in the area, Armenia’s power and influence have dramatically weakened. Georgia is poised to be side-lined should the two warring countries sign a peace treaty and embark on a road of cooperation. Among the outside powers, Russia and Turkey have both increased their influence. Russia has now placed its soldiers as peacekeepers in Azerbaijani territory 30 years after their initial withdrawal. Turkey has succeeded in a robust political comeback and increased military presence in Azerbaijan for the first time since the First World War and is poised to benefit further from any regional openings and cooperative initiatives. The Western presence generally suffered from a lack of strategy, weak interest, and general absence. As a result, national (i.e., The U.S., EU, France) and institutional (i.e., the OSCE and its Minsk Group) influences weakened significantly.

Russia’s main goal for the region has been to project itself as the dominant military and security actor and keep the Western powers, such as the U.S. and the E.U., out. With the deployment of 2.000 Russian peacekeeping forces in Karabakh, Russia now has troops in all three South Caucasus states. With the withdrawal of the Armenian forces from Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia has become a de facto patron in this area. It has already introduced Russian as a second language in the region. Russia is not only present militarily in Karabakh, but it also operates a military base with nearly 3.000 military personnel in Gyumri, Armenia. Additionally, Russia defends Armenia’s borders with Turkey and Iran, secures the transit route between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, and will play a crucial role in a future corridor to Nakhichevan from Azerbaijan through Armenian territory. This entails a strong presence in the security sector in the South Caucasus and a significant loss of Armenia’s sovereignty.

Although Russia has lost its most significant leverage over Azerbaijan -i.e., the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict – it retained some of its leverage by deploying Russian peacekeepers on Azerbaijani territory and the newly signed agreement between the two countries. Moreover, in the post-war environment, Russia has enforced its position as the leading security actor in the South Caucasus through its exclusivity in brokering the ceasefire and its deployment of “peacekeeping forces” without an international mandate. However, Russia is challenged by Turkey, Iran, and China, especially regarding economy and transportation. Moscow is “dragging its feet” to negotiate a final solution to the conflict, which might represent its policy of taking advantage of conflicts rather than solving them. Yet, as noted by Stefan Meister, this “(…) can only work as long as Russia has sufficient resources to back it up with military force.”

As the victorious actor after the war, Azerbaijan increased its power in the region. Not only by being able to change the facts on the ground but also because it psychologically overcame its long-suffered humiliation of losing the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and the occupation of its territory by its historical opponent in the early 1990s. Besides regaining territory lost in the First NK War, Azerbaijan has already invested USD 3 billion in the reconquered areas, building infrastructure and housing facilities with the intention of future resettlement of the 700,000 Internally Displaced People (IDP) who had to leave their homeland in the early 1990s. Moreover, it will undoubtedly continue to benefit from the close security relations it has established with Turkey and Israel in the run-up to the war. Finally, any economic cooperation and the possibility of linking its Nakhichevan exclave through Armenian territory will eventually connect Turkey to Central Asia and China through Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea, making it an essential link for China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Georgia was alarmed that Russia had increased its military presence in the South Caucasus and was concerned about further Georgian isolation, especially if the warring countries could move forward with bilateral cooperation. The post-war challenges for Georgia principally lie within the economic domain, primarily as consequences of future transport routes that might challenge Georgia’s position as a vital regional transit country.

In the latest war, Armenia lost territory that it has been controlling since the early 1990s and, as such, is seen by many as the clear loser of the war. However, the country could turn this into a positive sum if it can domestically overcome the objections of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians and ultra-nationalists and gain support for further liberalisation, democratisation, and normalisation of its relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan. This would undoubtedly end its hitherto isolated position in the region, creating and strengthening its connections with other regional countries and Europe. In turn, this would weaken its dependency on Russia, thereby strengthening its sovereignty and independence. Such a development would also help the Armenian economy to develop. Nevertheless, much of this depends on developments in Armenian domestic politics.

Like Russia, Turkey has increased its foothold in the region but has not yet been able to challenge Moscow’s hegemonic position. Turkey’s close relationship with Azerbaijan, as reflected in the unique place it obtained in the Shusha Declaration of 15 June 2021, between the two countries, together with its re-established military presence in the region after more than a century, sets it up for a future stronger position if, and when, Russia withdraws its peacekeeping forces from the area. Should it be successful, the normalisation process between Armenia and Turkey will also increase Turkey’s position in the region by establishing further land connections between Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan. It will further realise Turkey’s long-term goal of gaining direct access to the Caspian Sea and beyond, bypassing Iran, and becoming a transfer and transit hub for this region to Europe. Moreover, Turkey is poised to benefit from the reconstruction of the liberated territories of Azerbaijan and the successes of the Turkish-produced drones and other military systems used in the war by Azerbaijan against Russian-armed Armenia.

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War further decreased Iran’s role in the region. Although it is the only country with relations with Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, it did not participate in the war or the settlement. Iran cannot compete with Turkey and Russia in the post-war environment regarding security issues, political influence, or economic infusion. In contrast to Turkey and Israel, Azerbaijan has not invited it to rebuild areas bordering Iran due to its tense relations with Azerbaijan. Iran has held a seemingly pro-Armenian position for years, despite not being involved in the conflict and not supplying any military gear to Armenia. The fear of possible inducements of Iranian citizens of Azerbaijani and Turkic origin has created a tense atmosphere. Furthermore, and especially problematic for Tehran, the military cooperation between Israel and Azerbaijan has resulted in solid condemnations from Iran and even stronger reactions from Azerbaijan.

The war and the subsequent ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia can only be described as a spectacular failure by the EU and the US in their many efforts to contribute to stabilisation, confidence building, and conflict resolution in the region through the OSCE Minsk Group and other platforms since 1992. The OSCE Minsk Group format had been the main multilateral framework for negotiations since the end of the First Karabakh War, but it was side-lined this time. Furthermore, France, the co-chairman of the Minsk Group and front representative of the EU in the region has been criticised by Azerbaijan -and Turkey- strongly for its pro-Armenian stand during the second war, thereby weakening its and EU’s position in the region.

Over the past decade, the regional powers and the security environment shaped by the interaction between Russia and Turkey have increasingly dealt with issues related to security. Both the EU, which has declared its readiness to contribute to peace in the South Caucasus, and the U.S., where the Biden Administration is stressing its willingness to push for more U.S. presence on the global stage, have significantly weakened in terms of influence when it comes to dealing with hard security issues in the region. However, it must be noted that Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine might change this picture. We see the EU already taking a position in the bilateral negotiations between Azerbaijan and Armenia, and the US stepping up in direct negotiations between the two states since May 2023.

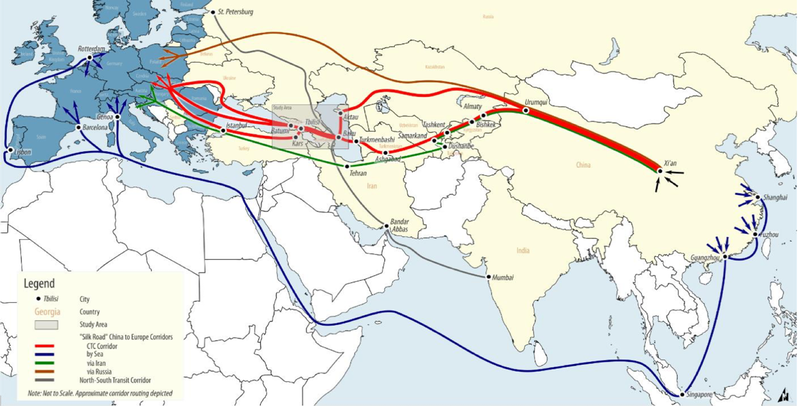

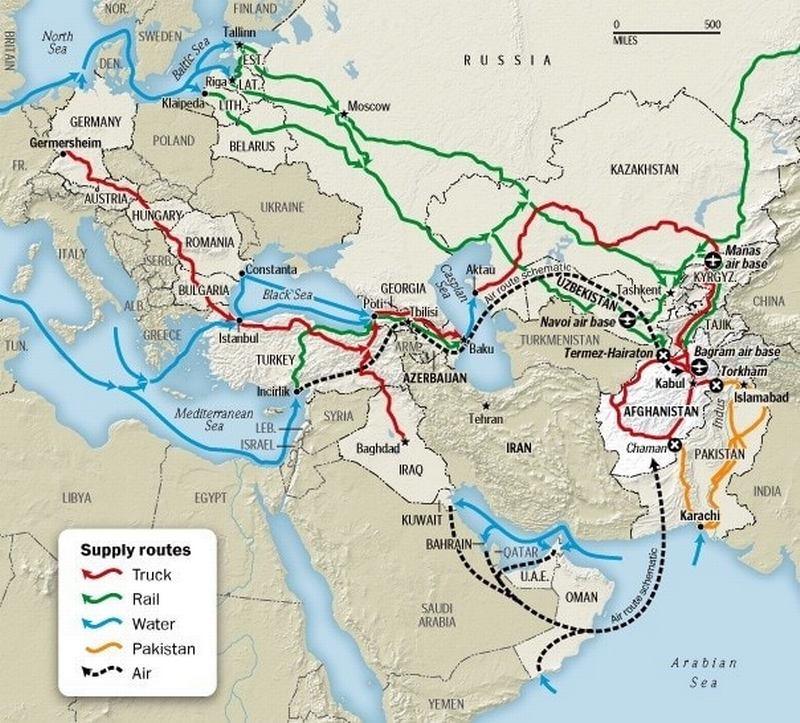

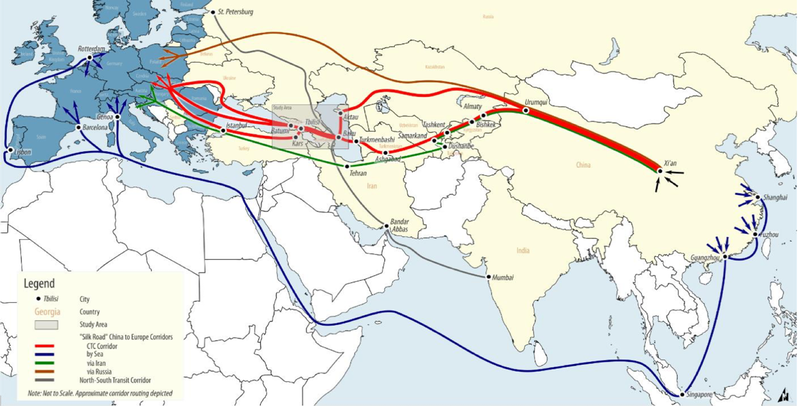

As the geopolitical changes since the 2nd NK War have somewhat opened the region, the most likely future change will be experienced in its regional and international connectivity. The outcome of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine can have further implications for the degree and extent of interregional connections and might influence the likelihood of realising the different options. Some of the already discussed alternatives within transport corridors, rail connections, and energy supplies routes are summarised below:

- North-South Corridor: International North-South Transport Corridor, a projected rail route stretching from Finland through Russia to the Persian Gulf and India.

- Middle Corridor: A route carrying goods between China, Central Asia, Turkey, and the European Union via the South Caucasus.

- East-West Corridor: A transit route envisioned at the end of the Cold War, carrying energy resources as well as other goods between Europe and Central Asia, going through the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, and Turkey, eventually linking up with China in the East and Pakistan and India in the South.

Map 5: The proposed Trans-Caucasus transit corridor and alternate routes. Source: Improving Freight Transit and Logistics Performance of the Trans-Caucasus Transit Corridor, World Bank, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33554/Improving-Freight-Transit-and-Logistics-Performance-of-the-Trans-Caucasus-Transit-Corridor-Strategy-and-Action-Plan.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed= - China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Including the China-Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor that runs through the South Caucasus, though Beijing has not yet invested in significant infrastructure or transport projects. It has provided sizable funds for transit infrastructure, digital infrastructure, and other projects in Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia.

- The Zangezur (Syunik in Armenian) Corridor: Connecting Nakhichevan with Azerbaijan through Armenian territory encompasses controversy about who will control the route. While Azerbaijan insists on possessing control over the route and points to the Lachin corridor that connects Armenia to Nagorno Karabakh across Azerbaijani territory, Armenia adamantly opposes any Azerbaijani control on its territory, lets it would lead to further claims in the longer term.

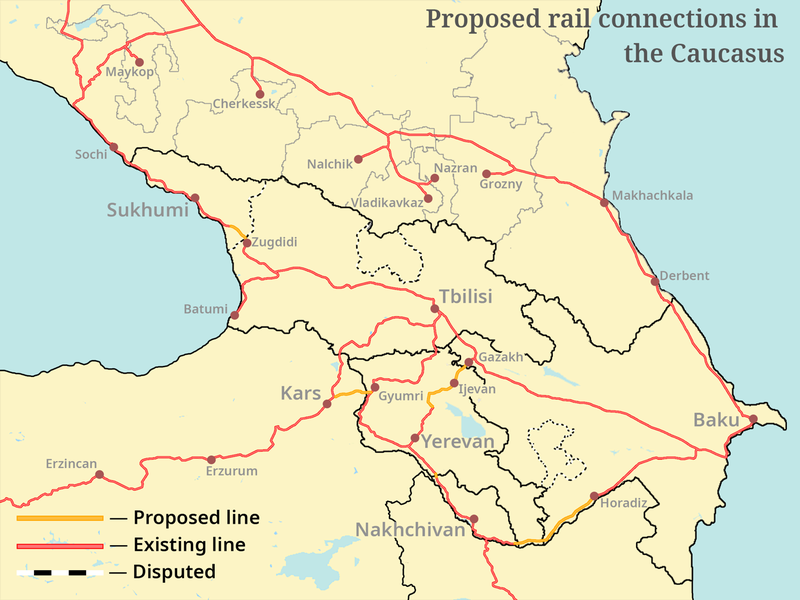

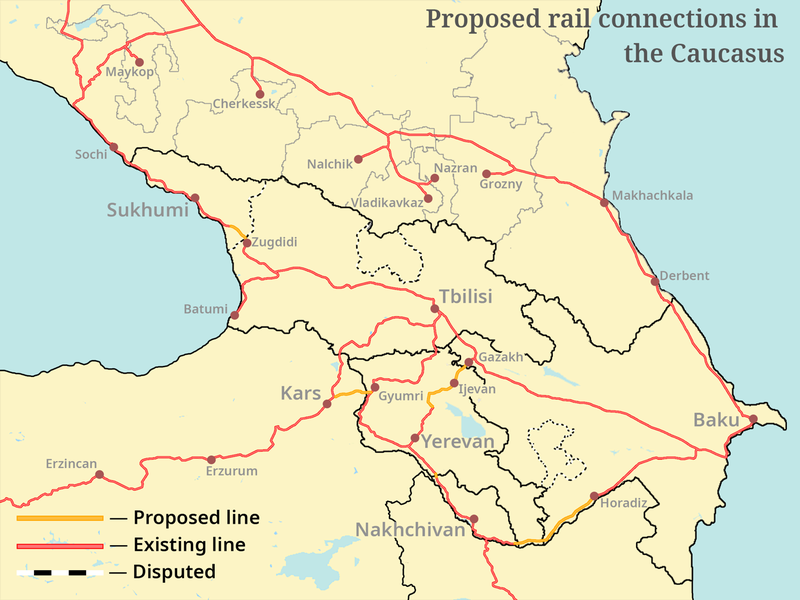

- The Arax(es) Rail Link: The primary railway connection between Azerbaijani and Armenia, built between 1899 and 1940 but damaged and later destroyed during and after the Nagorno-Karabakh War. Azerbaijan announced in February 2021 that it had started reconstructing the line on its territories. Realising this project would put the region at the centre of a future Black Sea–Persian Gulf rail link.

Map 6: Transport corridors Europe-Caucasus-Central Asia (TRACECA), 2021. Source: https://aze.media/transport-corridors-europe-caucasus-central-asia-discussed-between-head-of-traceca-and-azerbaijani-foreign-minister/ - Gyumri–Kars railway: Directly linking Armenia and Turkey would facilitate trade between the two countries and between Nakhichevan and Turkey and benefit Azerbaijan, Iran, and Russia.

- If the Araxes rail link is realised, Iran might need to shelve its costly project for the Astara–Resht line and instead use its existing rail network through Julfa across the border with Nakhichevan to further connect with Azerbaijani and Armenian lines.

- Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) Railway: A massive project that kicked off in 2017, connecting Turkey, Georgia, and Azerbaijan plus Europe to Central Asia and China.

- Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Oil Pipeline: operative from 2006. This pipeline carries oil from Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey and then via the Mediterranean to Europe.

- Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) Natural Gas pipelines run parallel to BTC and carry natural gas primarily to Georgia and Turkey. It has the potential to supply Europe with Caspian gas through the planned southern gas corridor and also to carry gas from Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan.

- Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP): a section of the Southern Gas Corridor that became operative in 2020. It carries gas from the Caspian Sea through Turkey to Europe.

Map 7: Proposed rail connections in the Caucasus. Source: https://oc-media.org/features/is-an-interconnected-caucasus-on-the-horizon/

- Baku–Supsa oil pipeline runs from the Sangachal Terminal near Baku to the Supsa terminal in Georgia. It transports oil from the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field and is operated by British Petroleum (BP). This pipeline’s history has been problematic; the Russian invasion of Georgia allowed Russia to take control of a short length of the pipeline, and there have been several spills and thefts. Although there is potential for expansion, there are no plans to date.

- Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (proposed) is a pipeline transporting gas from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan across the Caspian Sea via an undersea pipeline. It is also known as the South Caucasus Pipeline Future Expansion (SCPFX) due to its connection with the South Caucasus Gas Pipeline.

The geopolitical impact of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

Mustafa Aydın and Siri Neset

The consequences of the Russian war on Ukraine are impossible to grasp as the situation is still evolving. However, we do know that the results will be severe and extensive. In general, observers in the South Caucasus (SC) perceive the Russian aggression as a reaction to Ukraine’s desire to choose its future, which resonates across the South Caucasus.

It is not just the war that poses a risk for the SC countries– even if one considers increased refugee flows, Russian emigration, and escalation in the Karabakh region – it is the different consequences of the various possible post-war scenarios. Regardless of Russian victory or defeat, we will most likely see a bitter, isolated, and weakened Russia that potentially would pose a greater risk vis-à-vis the SC countries, for example, by using frozen conflicts as leverage.

Turkey’s regional role might increase as a balancer vis-a-vis Russia, a gateway to the West, and a transport corridor. This possible increased role would be strengthened with the success of the Turkey-Armenian normalisation process. This would open the region, decrease conflict behaviour, and defuse the consequences of Russian spoiler behaviour in using this conflict as leverage.

The Caspian region will become more critical regarding energy supplies and a transport corridor for the EU and Europe. This would imply an enhanced geo-strategic and commercial role on the East-West corridor, from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, at a critical time when everyone wants to circumvent Putin’s Russia. However, much of this depends on the Black Sea security environment, which has been a concern for littoral states for quite some time. The Romanian president first said, “The Black Sea is turning into a Russian lake, “ in 2005. Then, President Erdogan stated the same in 2016 to NATO Secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg with a more significant impact.

Nevertheless, NATO’s power in the area has not increased, and Russia has been able to increase its dominance further. Russia strengthened its military build-up in the region after the annexation of Crimea; primarily, it has pursued increased control over the seas surrounding Crimea and eastern Ukraine, particularly the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait. Turkey then lost its naval superiority in the Black Sea to Russia. The Russian invasion could cut Ukraine’s access to the Black Sea by taking control of the Mariupol and Odesa regions. This will enable Russia to control the entire Ukrainian coastline, landlocking Ukraine and providing a land corridor from Russia to Crimea and Transnistria in Moldova. There were also alarming reports that drifting mines released by Russia have been detected in the Western Black Sea from the Odesa port to the Bosporus. If these reports are valid, this behaviour will seriously damage the prospect of developing the newly discovered oil and gas fields within the Turkish Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the transport and trade routes in and through the Black Sea.

For Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, the Russian invasion of Ukraine entails (new) security risks to a region already burdened by the security environment following the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. For Armenia, the Russian peacekeeping forces within Nagorno-Karabakh could influence the Armenian government and public opinion in line with Russian interests. Notwithstanding, the general military build-up within Armenia proper might also risk the elected government’s degree of self-rule. For Azerbaijan, one might expect a decreased tolerance on the Russian part for Azerbaijan’s geo-strategic role (together with Turkey) regarding energy strategy/policies. Russia might pressure or influence Azerbaijani decision-making by increasing or decreasing its room for manoeuvre in the post-Second Nagorno-Karabakh War environment. Georgia might experience a worsening situation in the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and Russian attempts to project power through this conflict. Russian propaganda may also increase in Georgia, escalating societal and political polarization. All the countries in the region will have to reduce the consequences of Russian pressures and protect national sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence. Thus, international laws and regulations regarding territorial integrity must be reinforced for the region. If Ukraine’s territory changes due to the war, this would have potentially grave implications for the countries in the South Caucasus by the precedent it entails.

Besides the severe security risks the region may encounter, the South Caucasus has already experienced significant economic pressure due to the war and, mainly, the massive sanctions imposed on Russia. Factors such as the downward spiralling of the Russian Ruble and the decrease in trade and economic activity are taking effect. Furthermore, all three countries have large diaspora communities in Russia that regularly send money back to their relatives; anecdotal evidence suggests a decline in these remittances even before the sanctions came into effect. Russia may also try to use its networks and dependency structures in the three countries to circumvent the sanctions, putting the countries in confrontation with the US, EU, and other parts of the international community.

The South Caucasus has a long history of conflicts and Russian dominance to varying degrees that may now continue and even worsen. Still, there is also the possibility that the shock of Russian actions in Ukraine and the changing international order might change the historical behavioural patterns. In a worst-case scenario, the spill-over effects of the Russian war on Ukraine might lead to further divisions between the countries of the South Caucasus to stay on Russia’s good side to avoid Russian aggression and obtain maximum autonomy. In a best-case scenario, the spill-over effects of the war could lead to unification against a common threat.

To illustrate the worst-case scenario, on 22 February 2022, only two days before Russia invaded Ukraine and one day after the Russian recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states, Azerbaijan signed an agreement with Russia. The agreement was an “allied cooperation” agreement. It attempted to bring Azerbaijan’s relations with Russia to the level of Armenia-Russia relations and secure Azerbaijan’s gains after the second Karabakh War. However, the 43-point agreement also outlines some points that might hamper Azerbaijan’s room for manoeuvre in international relations (points 4 and 7) and its aspiration as an energy supplier with Turkey and the Caspian to Europe route (point 25). The meeting was further described as a humiliation of President Aliyev in how it came about, the meeting procedures, and the meeting date, i.e., the Treaty of Turkmenchay, which went into effect on 22 February 1828. The Persian Empire ceded the control of several areas in the South Caucasus to Russia, including the territory now south of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

However, there have been some developments that reflect a better scenario. One such event is the evolving bilateral peace talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan, facilitated by the EU and without Russian involvement (although Moscow is not expected to step aside).

Following on from a meeting between senior representatives from Armenia and Azerbaijan coordinated by the EU in Brussels on 30 March 2022, another meeting was held on 6 April, after which the European Council President Charles Michel said: “The leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan have met and agreed to “rush toward a peace agreement.”

Furthermore, the fact that the three South Caucasian countries share many challenges from Russia could potentially be a unifying force. For the time being, though, such a process lacks a suitable platform which is probably needed given that the region has had few experiences of cooperation - the exception being during the Soviet era when the countries were closely integrated but isolated from the outside world.

It remains to be seen if US negotiation efforts of spring 2023 might help unify the three countries and provide the required platform to further regional and international policy and trade collaboration.

National Perspectives on the Changing Geopolitics

Armenian perspectives

Richard Giragosian

The geopolitical landscape of the South Caucasus has undergone a significant shift in the wake of the war for Nagorno Karabakh that erupted in September 2020. The post-war reality has left the region in uncharted territory. Specifically, the unprecedented vulnerability in the area led to Armenia and Azerbaijan accepting the terms of a Russian-crafted agreement in November 2020 that effectively ended the war and triggered the immediate deployment of 2000 Russian peacekeepers to the region for an initial five-year deployment. The agreement introduced a cessation of fighting, consolidated significant territorial gains by Azerbaijan, and affirmed Armenia’s defeat. While the acceptance of the agreement saved lives and preserved the remaining territory of Nagorno Karabakh in the hands of the local Armenians, the conflict remains unresolved with several outstanding questions, ranging from the status of Karabakh to the terms of the withdrawal and possible demobilisation of the Karabakh armed forces, making further diplomatic negotiations essential to ensuring security and stability.

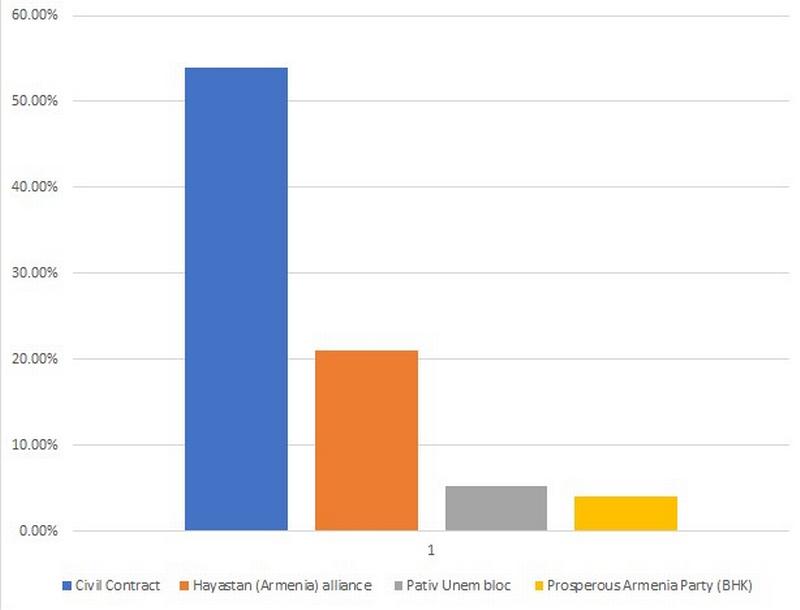

Given the lack of preparation of Armenian society for the severity and scale of the losses from the 2020 War, the government of Nikol Pashinyan faced an immediate series of protests, leading to calls for the prime minister to resign and demanding accountability. Against a simmering shock over the losses from the war, the challenges from an already polarised Armenian society seemed likely to end Armenia’s experiment with democracy. Yet since he came to power after the “Velvet Revolution” of 2018, Prime Minister Pashinyan has demonstrated impressive resilience. As the Armenian leader who has “lost Karabakh”, Pashinyan weathered a severe crisis, facing a revolt from his senior military officers and forcing an early election in June 2021.

The June 2021 re-election not only re-granted Pashinyan legitimacy with a fresh mandate in the newly elected Parliament but also weakened the chance for a political comeback by the old-guard authoritarian leaders that were ousted in 2018. It also instilled self-confidence and allowed the Pashinyan government to embark on a new strategic leadership course capable of adapting to post-war reality. Yet, such optimism has proven premature as Armenia struggles with challenges. With sporadic clashes along the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, post-war instability has increasingly been driven by a widening of the battlespace well beyond the confines of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This expanded context of the conflict poses a new threat to broader regional stability in the South Caucasus.

Armenia still faces several general challenges, including a prolonged war, overcoming post-war state paralysis, and early elections. We elaborate on these challenges below.

1) A prolonged state of war. Armenia remains constrained by a prolonged state of war, driven by two pressing issues: uncertainty over the urgent necessity to secure the full release of Armenian prisoners of war and non-combatant civilians from Azerbaijani captivity and insecurity from a series of border incursions by Azerbaijani military units that began in May 2021 along with several contested areas on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. This virtual state of war is further exacerbated by the delayed resumption of diplomatic negotiations necessary to transform the fragile Russian-imposed ceasefire agreement of November 2020 into a more durable peace agreement over Nagorno Karabakh.

2) Overcoming post-war state paralysis. With limited diplomatic engagement with Azerbaijan for several months after the war’s end, Armenia was unrestricted by a lack of accountability for the unexpected defeat in the war and a pronounced perception of state weakness and paralysis. This was seen in the Armenian government’s failure to adapt to the post-war reality, the absence of a new diplomatic strategy, and a failure to adjust the country’s military posture or defence reform, contributing to a “state of denial.” Despite achieving hard-fought democratic gains since coming to power, the government’s inadequate response to the demands of the post-war crisis has also fostered a perception of state paralysis.

This was exacerbated by the delayed resumption of diplomatic negotiations and uncertainty over the vague and incomplete terms of the Russian-imposed agreement that ended the war. Although that agreement resulted in an essential cessation of hostilities that allowed for deploying a Russian peacekeeping force to Nagorno Karabakh, it fell far short of either a peace deal or a negotiated resolution to the conflict itself. Moreover, it deferred the status of Nagorno Karabakh to a later stage of diplomatic negotiations and left several important issues unanswered, such as military demobilisation and border demarcation.

3) Moving to early elections. The domestic crisis was further marked by political polarisation that fostered a stalemate between a largely unpopular and discredited opposition and a government with no viable replacement. A reluctant recognition led Prime Minister Pashinyan to accept the necessity for early elections in June 2021 to diffuse the domestic deadlock. The polls were also characterised by intense polarisation and increasingly inflammatory language.

Nevertheless, with the return of former President Robert Kocharian as the frontrunner of the opposition’s attempt to unseat Pashinyan, the election was defined by a contest of personalities rather than a competition of policies. For the Armenian electorate, it was also a choice between an appeal to the authoritarian “strong man” leadership of the past versus continued confidence in the democratic reforms of the Pashinyan government.

Despite some expectations of a more competitive contest, the opposition failed to pose a significant challenge to the incumbent government. Nikol Pashinyan emerged with an impressive victory with nearly 54 % of the vote, securing a decisive majority of 71 seats in the 107-seat parliament. The election renewed the incumbent government’s legitimacy, political stability, and democratic resiliency.

The new post-war environment

After the war’s end, there were many questions about what came next, with no clear answers and even fewer certainties. When Armenia accepted the terms of a Russian-imposed agreement that ended the war, it also ceded territory to Azerbaijan. While the agreement halted the fighting, it also raised several questions over the “status” of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians, their sovereignty or autonomy, and their legal standing.

In the first meeting between the Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders since the start of the war in late September 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin succeeded in brokering a preliminary resumption of diplomatic negotiations. The 11 January Moscow meeting between Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan focused on restoring trade and transport links, including granting Azerbaijan access to its exclave Nakhichevan through Armenian territory. All sides assented to creating a tri-partite “working group” on a deputy ministerial level to manage the “practical modalities of restoring transport links between Armenia and Azerbaijan.”

The weakness of the Armenian side allowed Azerbaijan to dictate terms in this first return to the diplomatic arena, including protesting the visit of the Armenian foreign minister to Karabakh. For his part, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was firm in dismissing Azerbaijani protests but warned Armenian officials against “emotional” statements when visiting Karabakh. The Russian foreign minister also specifically downplayed any urgency to settling the “status issue” of Karabakh, explaining that Moscow prefers to “leave it to the future” and to instead focus first on “confidence-building measures” and other issues. Armenia conceded by agreeing to defer the status issue to the later stages of negotiations, but with a focus on the return of all prisoners and detainees, practical confidence-building measures, and de-escalation as immediate concerns.

Despite the post-war tension and insecurity, there were two crucial breakthroughs. The first came in September 2021 with a meeting of the Armenian and Azerbaijani foreign ministers on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York. With the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs, this meeting marked an essential return to diplomacy between Armenia and Azerbaijan. This resumption of diplomacy, which included a planned visit to the region by the OSCE Minsk Group, is crucial to widening post-war security in the wake of border tensions since May 2021. A follow-up ministerial meeting was held in Paris in early November 2021. Such diplomatic re-engagement offers more than a reliance on negotiations over the force of arms and acts to lessen the risk of resumed hostilities and paves the way for continuing the return of Armenian prisoners from Azerbaijani captivity.

The issue of returning prisoners from Azerbaijan is critical for Armenia and is an emotional element contributing to the Armenian perspective of an ongoing war. The continued holding of the prisoners contributes to an atmosphere of mistrust, especially as the Armenian side returned all Azerbaijani prisoners immediately after accepting the ceasefire agreement.

Some observers see the 45-day war as a victory for Turkey as much as for Azerbaijan. This view stems from the Turkish military’s unexpectedly direct engagement in waging war. Although this effort succeeded in seizing large areas of territory and capturing parts of Nagorno Karabakh for Azerbaijan, several factors diminished the possible gains for Turkey. There were some unexpected results for Turkey after Russia’s belated engagement, which could be seen in the controversy over Russia and Turkey’s future peacekeeping missions in the region. Moscow seems to have reneged on its earlier promise of a more direct role for Turkish peacekeepers. The final role for Turkey appeared more symbolic, with a minimal position in peacekeeping planning and supervision in Azerbaijan. This effectively gave Russian peacekeepers the dominant role in the region.

Yet, at the same time, Turkey regained its lost role as the primary military “patron state” for Azerbaijan, replacing Russia as the leading arms provider and source of weapons. This was also matched by a “power exchange” defined by a deeper trend of a shifting balance of power, with a resurgent Turkey empowering a confident Azerbaijan after the successful military campaign against Nagorno Karabakh. For Armenia, the primary perception is that despite unprecedented military support for Azerbaijan, Turkey came away from the 2020 war with less than expected. In some way, that Armenian perception has allowed the Pashinyan government to begin efforts to pursue normalisation with Turkey in late 2021.

Challenges/constraints and opportunities for regional cooperation

Despite the ceasefire agreement in November 2020 that ended the 45-day war, post-war stability and security has been undermined by three factors:

- First, the absence of diplomatic negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan exacerbates the fragility of the ceasefire agreement. It poses a significant obstacle to transforming the ceasefire into a peace agreement.

- Second, the tenuous position of Nagorno Karabakh and the physical security of the Armenian population of Karabakh are overwhelmingly dependent on the presence of Russian peacekeepers.

- Third, the lingering burden of Armenian POWs is still in Azerbaijani captivity. Despite the November 2020 ceasefire agreement, which called for exchanging all POWs and prisoners, Azerbaijan has repeatedly resisted, offering only partial releases of small numbers of Armenians.

Against this backdrop, there is also a more recent crisis of insecurity. This was triggered in May 2021 with an escalating confrontation between Azerbaijan and Armenia consisting of border disputes and a series of border incursions by Azerbaijani units into Armenian territory.

The insecurity also triggered a Russian military build-up in southern Armenia and at strategic points along the Armenian border with Azerbaijan. Although separate and distinct from the Russian peacekeeping operation in Nagorno Karabakh, this expansion of the Russian military presence secures the Russian role in controlling and managing the potential restoration of regional trade and transport links, including the planned establishment of road and railway links between Azerbaijan and its exclave Nakhichevan through southern Armenia.

The enhanced presence further means a subsequent control of the Armenian border with Azerbaijan by Russian border guards, a development with strategic implications, as an inherent threat to Armenian sovereignty and independence given existing Russian control over two of Armenia’s four external borders: complete control over the Armenian-Turkish border and supervisory authority and oversight of Armenia’s border with Iran.

More broadly, the escalation of tension along the Armenian-Azerbaijani border is part of a trend of increasingly serious confrontation, which began in May 2021 with an incursion of Azerbaijani military personnel and then escalated with the interference over Iranian trucks passing through southern Armenia. In this context, it is notable that this escalation has little direct relationship with either the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict or the Russian peacekeeping presence. Instead, the tension between Armenia and Azerbaijan poses a new challenge from a broadening of post-war confrontation to a bilateral dimension. This escalation is significant for three reasons:

- First, the tension on the ground and sporadic clashes have revealed a dangerous disconnect between more positive signs of progress on the higher level of diplomacy between the heads of state and developments on a local level. This is especially worrisome as local forces on the ground may seriously impede efforts by the leaders to de-escalate tension and move forward with essential steps seeking post-war stability.

- Second, there is a concern over implementing the looming preliminary agreement on restoring regional trade and transport. In this context, the viability of the planned first-stage agreement offering Azerbaijan new road and railway links to its exclave of Nakhichevan may be impacted by an absence of security on the ground.

- Third, the escalation of tension also erodes recent gains and progress in a “return to normalcy,” marked by a more predictable and calmer post-war environment. Such an environment is essential for successfully resuming diplomatic engagement and establishing confidence-building measures between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Despite the promise of diplomatic re-engagement, Azerbaijan’s counter-productive maximalist stance and Armenia’s still not fully adjusted position to the post-war reality have led to three troubling trends:

- The military victory for Azerbaijan suggests a dangerous confirmation of “might make right,” with the war being seen as a validation of force of arms based on an acceptance of applying a military solution to the Nagorno Karabakh conflict.

- An unfortunate result of the war was the perception of the inherent weakness of democracy, as seen by the military victory of a larger, more powerful authoritarian state over a small infant democracy. In addition to the broader lesson, this will weaken and imperil continued democratisation, political will, and commitment to reforms in Armenia.

- The post-war geopolitical context raises concerns over the future of regional security and stability, considering Russia’s unilateral deployment of peacekeepers and the return of Turkey as Azerbaijan’s primary military patron state. Azerbaijan will be challenged to maintain its precarious balance between Turkey and Russia. At the same time, the inherent rivalry between Ankara and Moscow may only resurface, with the South Caucasus serving as the arena for a new competition between regional powers, which could trigger a response from Iran.

A breakthrough in the relationship between Azerbaijan and Armenia came when the meetings of the tripartite working group on regional trade and transport resumed, and Armenian Deputy Prime Minister Mher Grigoryan reported significant progress in these talks. Armenia initially suspended the meetings in response to Azerbaijani border incursions in May due to Baku’s intransigence over the return of prisoners. More specifically, the working group’s resumed negotiations resulted in an essential preliminary agreement reaffirming Armenian sovereignty over all road and railway links between Azerbaijan and its exclave Nakhichevan through southern Armenia. It also confirmed unilateral Russian control and road and rail traffic supervision, including legal customs control and access provisions. The successful agreement over the restoration of regional trade and transport is limited to the links between Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan as the first stage, however, with the planned reconstruction of the Soviet-era railway link and the construction of a highway.

The broader second stage of regional trade and transport encompasses a more expansive (and significantly more expensive) strategy that includes the reopening of the closed border between Turkey and Armenia and the restoration of the Soviet-era railway line between Kars and Gyumri, as well as the eventual extension of the Azerbaijani railway network to allow Armenian rolling stock from southern Armenia through Baku on to south Russia.

Discussions in this tripartite working group include a Russian pledge to provide a new gas pipeline running through Azerbaijan to deliver Russian natural gas to Armenia, partly as an alternative to Armenian dependence on the Russian sole gas pipeline from Russia that runs through Georgia. The tri-partite (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia) working group of regional trade and transport stands out as the only area of progress. It represents a “win-win” scenario for post-war stability, with the economic and business opportunities significant for Armenia in overcoming isolation, Azerbaijan in developing the regained districts, and Russia, which now controls regional integration. However, the lack of specific information on the status of the talks increases the risk of misinformation or disinformation. Additionally, with Russian management of the process, there is an added danger of external manipulation, with both Yerevan and Baku vulnerable to Moscow’s agenda.

Armenia as an actor in the South Caucasus region

For a small country like Armenia, one of the more critical challenges is to attain a degree of relevance and strategic significance. As a landlocked country in a relatively remote region, garnering recognition and bearing has been difficult. In addition to the lingering tension with Turkey, the simmering conflict with Azerbaijan and the mounting unreliability of Russian patronage, the Armenian foreign policy has been defined by its historical understanding as a state founded on the survival of a genocide.

There are several fundamental limits and challenges to the defence and development of Armenian statehood. The first of these limits is seen in the country’s unforgiving geography, as the lack of secure access to the World seas has contributed to its isolation as a “landlocked” country. Second, the geographical limits also pertain to neighbouring countries, as two of the country’s four borders remain closed. These geographical constraints have magnified the importance of Georgia as the main route for Armenian exports and imports, especially given the limits of using Iran as an effective alternative. They have also led to the development of a “siege mentality” within Armenia.

This reality of inherent limitations and challenges has spurred the need for Armenian foreign policy to seek greater space for manoeuvre, demonstrated by the strategy of complementarity, which strives for strategic balancing and greater options. Despite some setbacks and mistakes, this “small state” strategy has generally managed to mitigate the damage from gradual over-dependence on Russia and maximise opportunities. The latter success in seizing opportunities was most evident in Armenia’s rare second chance to regain and restore strategic relations with the European Union (EU), such as with the successful negotiation and conclusion of the Armenia-EU Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA). As a country coerced to sacrifice its earlier Association Agreement and related Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the EU in favour of joining the Russian-dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU), this was a significant achievement.

Armenia seems to be moving quickly to embrace a more forward-looking strategy toward Europe due to an updated understanding of the limits within the EU`s Eastern Partnership program and perceived changed dynamics between EU member states. This policy is expressed through an approach to pursuing closer ties with Germany and France. While it is based on an assessment that Germany is the most influential economic actor within the EU, it is also rooted in recognition of the emerging role of France as a pivotal geopolitical power, especially as French President Macron is emerging as the primary driver of EU foreign and security policies in post-Merkel Europe. Although both factors seek to exploit Armenia’s special relationship and close ties with both countries, it is also in part a response to a recent French initiative to engage Russia, which Armenia sees as an opening and opportunity to forge a more significant role as a strategic “bridge” or “platform” to guide closer EU ties to both Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU).

Conclusion: An Armenian perspective

Since Armenia’s Velvet Revolution in 2018, democracy has been strengthened by two back-to-back free and fair elections. Yet, despite substantial gains in reform and achievements in consolidating its democracy, Armenia’s credentials were not enough to safeguard the country from the impact of the 2020 war for Nagorno Karabakh. Most significantly, the war posed dangerous and distressing precedents for Armenia, standing out as a destructive demonstration of a victory of authoritarian Azerbaijan while seemingly reaffirming that there was a military solution to a political conflict. If left unchallenged, these dangerous precedents undermine Western values and elevate the force of arms over diplomacy.

Post-war Armenia now faces a new challenge from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. For over twenty years, Armenian foreign policy has been defined by a pursuit of “complementarity”, where Armenia struggled to maintain a strategic “balance” between its security partnership with Russia and its interest in deepening ties to the EU and the West. This policy has been difficult to maintain over the years, especially given the underlying trend of Armenian dependence on Russia, driven by security and military ties. Since the Second Karabakh War, the limits of Russian security promises to Armenia have become open and obvious. But with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Armenia now faces an even more imposing and perhaps impossible challenge to meet Moscow’s expectations for loyalty and support for Russian aggression against Ukraine. In the case of Armenia, however, concern and worry are somewhat offset by two factors.

First, the lack of direct military involvement in the Russian invasion provides Armenia with a degree of safety from the imposition of punitive measures and sanctions. However, there is a risk of Armenia becoming subject to secondary sanctions if Russian attempts to utilise Armenia to subvert or sidestep sanctions on Russian companies. The Armenian government is expected to try hard to avoid such risk given their demonstrable success in conforming to similar Western sanctions against Iran and considering past precedents of Western sanctions imposed on Russia for its 2008 war in Georgia and its seizure of Crimea in 2014, which never included Armenia.

Second, Armenia benefits from the advantage of geography. Armenia is over 1400 kilometres from Ukraine’s conflict zone and has no land border with Russia. As such, the country is far removed from the conflict and is not engaged in Russia’s war against Ukraine in any form.

For Armenia, both in terms of lessons for and from the war in Ukraine, perception is as important as reality, as defined by two reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine: First, a demonstrable double standard in both the media coverage and the concerted Western response to the war in Ukraine, in stark contrast to both elements of the 2020 war for Nagorno Karabakh. Second, despite significant differences and the distinctly different contexts between the Ukrainian and Karabakh wars, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has triggered a strong Western reaction that imposed punitive costs and sanctions against Russian aggression that were never invoked against Azerbaijan for the war in 2020.

Moreover, there is a certain degree of Armenian vulnerability comprised of four factors:

- Armenia is exposed to competing and contradictory demands from Russia for loyalty and submission, against expectations from the international community to stand against Russian aggression. This poses a strategic risk of Armenia’s isolation on the wrong side of history, misperceived as a supplicant state or pro-Russian vassal.

- In the face of more restricted room to manoeuvre and fewer options under Russian pressure, Western commitment to Armenia is in danger of coming into question, with a lack of Western understanding and patience, greater Russian intolerance, and diminished strategic significance of Armenia. These factors could enhance Armenian timidity and trepidation regarding Russia and impact Armenian commitment to the West.

- In that context, a third factor stems from the reality that the accidental “convergence of interests” between Russia and the West that was defined by a shared interest in post-war stability in Nagorno Karabakh no longer holds, with likely developments that include the demise of the OSCE Minsk Group as a mediating diplomatic format, new doubt over Russian support for Armenia-Turkey “normalisation,” and a questionable Russian commitment to the restoration of regional trade and transport in the future, as well as a more bleak outlook for a Russian-supported process of border delineation and demarcation between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

- The broader danger for Armenian domestic reform and democracy is the onset of new Russian pressure and a new Russian policy framework using post-war Armenian insecurity and Nagorno Karabakh as a key “pressure point” while leveraging Karabakh as the most attractive commodity to barter with Azerbaijan and Turkey.

In response, Armenian foreign policy has embarked on a more delicate diplomatic positioning, jockeying between placating and mollifying Russia while maintaining a bare minimum of support and commitment to the Russian side. This adaptive diplomatic response relies on a tactical policy of employing “strategic silence”, designed to do and say as little as possible while avoiding any open or outright defiance of Moscow. This is most clearly seen in the lack of statements by the Armenian Prime Minister or Foreign Minister. Instead, the Foreign Ministry spokesperson issued a diluted statement of support for a “diplomatic resolution” to Russia’s conflict with Ukraine. From this perspective, Armenia also exercises abstentions in key diplomatic votes in the UN and Council of Europe.

However, there are limits to the success of such “strategic silence” by Armenia, as demonstrated by Armenia’s reluctant vote in the Council of Europe against the move to suspend Russia from that body. Although Armenia’s position, as the only other country besides Russia to oppose that move, dangerously isolates it, there was little choice and even less of an alternative for Armenia. The danger now is that as Russia demands more significant support and open loyalty from Armenia, the diplomatic balance may be lost, threatening to push Armenia into a vulnerable and even more isolated position.

Beyond possible Russian demands for stricter Armenian submission, there is a genuine risk of Armenia facing a more assertive Russian policy to limit each of its neighbours’ sovereign choices and strategic options. This likely Russian pursuit of tightening control over the “near abroad” as a Russian-dominated “sphere of influence” may impose new limits and invoke greater demands on Armenia’s developing ties to the West while threatening to overturn hard-fought gains in Armenian democracy.

Azerbaijani perspectives on the geopolitical situation

Ayça Ergun

The outcome of the Second Karabakh War changed Azerbaijan’s perception of regional security structure and cooperation. It pushed Baku to modify its diplomatic language and international engagement, which had been developed based on the outcomes of the First Karabakh War in the 1990s, where the occupied territories were the number one issue on the agenda.

First, despite three decades of international engagement and diplomacy, Azerbaijan’s clear military victory realised what Azerbaijan had not earlier. The Second Karabakh War led to the de-occupation of many territories under the effective control of Armenia and broke the deadlock of diplomacy over the Karabakh issue.

Second, Azerbaijan perceives a shift in the regional security environment. Along with Russia, Turkey is now a key player in the post-war situation. Turkey has provided military, political, and energy infrastructure support to Azerbaijan since the 1990s, primarily with U.S. support and Western engagement. However, Ankara had no serious voice in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict other than the border closure with Armenia, which was part of Baku’s policy to isolate Armenia from regional projects during the occupation.

Third, Russia has obtained some leverage over Azerbaijan. Specifically, Russia now has an armed contingent stationed in Azerbaijan’s territory. The absence of Russian military forces has been a point of pride for Baku since their eviction in the early 1990s. The current Russian military contingent of peacekeepers is in place until 2025, with the chance of further extension. According to many among the Azerbaijani governing elite, after the failure of a diplomatic solution in 2014 and the previous clashes, the only possibility for a peaceful resolution is to allow Russian peacekeepers in the country in exchange for Moscow’s support to Baku and pressure on Yerevan. This led to the difference between the Madrid Principles and the modified Russian version, which suited Baku’s interests. The elite also saw the West as absent in conflict resolution long before the 2020 war. This was complemented by the apparent unpreparedness of the OSCE Minsk Group members to create a multinational peacekeeping force, which usually falls under its mandate to monitor and guide the relevant OSCE institutions such as the High-Level Planning Group.

In the post-war era, Azerbaijan saw more positive geopolitical trends (i.e., not Russian monopolisation) because of the increased Turkish role and influence in the region. At the same time, Azerbaijani authorities are sympathetic to Western involvement in the post-war situation, not to ‘balance’ Russia but to support the region’s development and help Baku and Yerevan achieve final peace. However, today there remain lingering suspicions, but not definite dismissiveness, regarding the reliability of Western involvement based on the disappointment of the 1990s.