The cost of doing politics in Ireland: What does violence against politicians look like and how is it gendered?

Irish elections, political culture and women in politics

What does political violence look like in Ireland?

Sources and timing of political violence

How to cite this publication:

Fiona Buckley, Lisa Keenan, Mack Mariani (2023). The cost of doing politics in Ireland: What does violence against politicians look like and how is it gendered? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2023:6)

Women who contest election in Ireland report experiencing political violence more often than men, experience different forms more frequently (specifically, degrading talk and false rumours), and are more likely to experience political violence with sexual connotations. Women are also more likely to report being less willing to run for election in future. These findings present challenges for efforts to improve gender equality in political representation in Ireland.

Key takeaways

-

75 percent of respondents have experienced at least one form of political violence.

-

Being subjected to degrading talk and false rumours is the most prevalent form of political violence followed by threats. Physical violence is least frequent.

-

Political party (another party and one’s own), digital media, and the community are prominent sources of political violence.

-

Political violence in Ireland is gendered, in its form, scope and consequences.

Irish elections, political culture and women in politics

Ireland uses a proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (PR-STV) electoral system. For local, national and European Parliament elections, the country is divided into a number of multi-seat constituencies or districts. Candidates from political parties and none, are listed alphabetically on the ballot paper. Electors vote preferentially for candidates. Due to the multi-seat configuration of constituencies, it is possible for a number of candidates from the same party to contest in the same constituency. The Irish electoral system creates incentives for politicians to cultivate their own vote, distinct from that of their party. This manifests itself in personalised campaigning during the election period, but also incentivises politicians to engage in a good deal of constituency work between elections. The Irish public respond to this with data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (2008) finding that the level of personal contact between public representative and constituent was highest in Ireland.

The personalised nature of politics in Ireland creates expectations that politicians are to be visible and available. Home addresses and personal mobile phone numbers are freely available. Politicians host clinics, whereby constituents can come to constituency offices and meet face-to-face with their public representative. The openness of Irish political culture is seen as an integral aspect of a healthy and functioning democracy. But this openness presents opportunities for perpetrators of violence against public representatives.

Simultaneously, international research has found that candidate-centric electoral systems are disadvantageous to women’s political representation (Thames and Williams 2010) and systems that cultivate clientelism, personalism and localism benefit male candidates, particularly in terms of campaign fundraising (Ballington 2003). Women are underrepresented in Irish politics - currently just 23 percent of the members of Dáil Éireann (lower house of parliament) and 25 percent of local councillors are women. To address the political underrepresentation of women, Ireland adopted a legislative party-based gender quota for national elections that came into effect in 2016, creating new opportunities for women, but in challenging the masculine norm that has traditionally defined Irish politics, it also has given rise to resistance.

Political Violence

Political violence occurs “when the goal of the violence is to affect political integrity and when the means by which the violence is conducted also violates the personal integrity of individuals involved in politics. Personal integrity can be violated by a range of acts and may be broadly categorised into physical and psychological violence (i.e. intimidation and threats) and can take place in the public or private sphere. Both forms of violence may have sexual connotations” (Bjarnegård 2018:690).

The Irish case-study

The survey population (2,141) consisted of any individual who contested the 2019 local elections or the 2020 general election in Ireland. The survey was conducted online. Research participants were invited to participate via email (where email address was known) or through a letter to their home address which contained a QR code to the survey. 362 usable responses were returned for a response rate of 16.9 percent. Women consisted of 38 percent of respondents which contrasts with 28 percent of the actual population, indicating a higher level of interest in the topic of the survey among female candidates.

Survey respondents were asked about their experiences of political violence during the election campaign. Those who were elected were also asked to share any experiences they had encountered while serving in office. Most questions were closed-ended and focused on occurrences of 1) degrading talk or false rumours; 2) threats; 3) physical violence; and 4) property destruction. Respondents were also asked whether someone associated with them had experienced any form of intimidation because of their connection with the respondent.

What does political violence look like in Ireland?

When asked if violence and intimidation is a normal part of politics in Ireland, of those surveyed, 15.6 percent said ‘yes, it is part of politics’; 51.7 percent said ‘no, but it happens sometimes’; and 32.7 percent said ‘no, it is not a normal part of politics’. Overall, 75 percent of respondents have experienced at least one form of political violence, with most respondents experiencing two forms. While physical violence is uncommon (10.2 percent), some 67 percent of respondents have been subjected to degrading talk and false rumours, 36 percent have been threatened, 27 percent have experienced the destruction of property and 33 percent recall their associates being intimidated. On the whole, those running in the 2019 local election were less likely to experience violence than their counterparts contesting the 2020 general election. The table above presents data on how often respondents who experienced political violence encountered different forms of violence.

For people who were subjected to degrading talk or false rumours, these were sexual in nature in 40 percent of cases. For those who experienced threats, a quarter were sexual in nature. While instances of physical violence are low, when it occurs, it is typically non-sexual in nature (82.9 percent).

|

Form of political violence |

Once |

A few times |

Several times |

Very often |

Total |

|

Degrading talk/false rumours |

4.24 |

42.37 |

32.63 |

20.76 |

100 |

|

Threats |

9.09 |

52.27 |

31.06 |

7.58 |

100 |

|

Physical violence |

37.50 |

42.50 |

17.50 |

2.50 |

100 |

|

Destruction of property |

20.39 |

55.34 |

22.33 |

1.94 |

100 |

|

Intimidation of associates |

10.08 |

58.82 |

26.89 |

4.20 |

100 |

Gendered differences

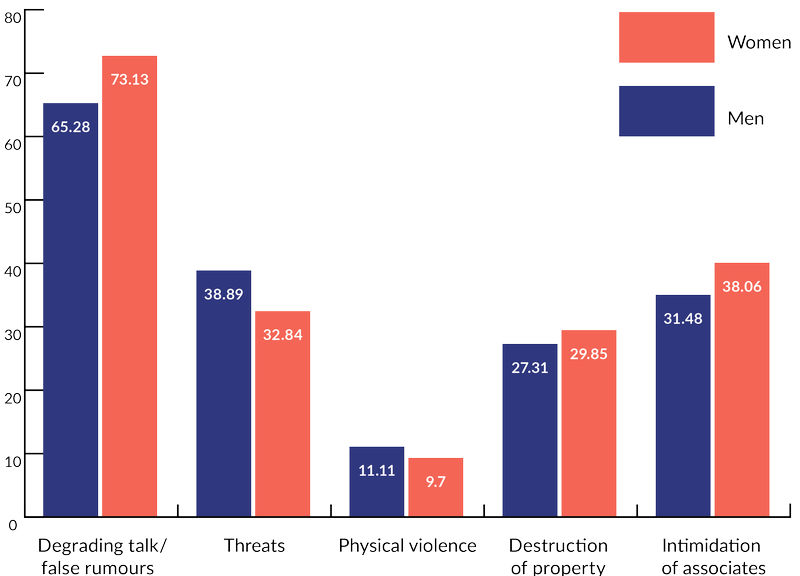

Women contesting election in Ireland experience political violence more frequently than men. Holding other variables constant (age, political prominence, party affiliation), women experience instances of political violence at a rate that is 1.2 times greater than that of men. Women are particularly vulnerable to degrading talk and false rumours; they are 2.3 times more likely to experience this than men. Furthermore, women who are subject to false rumours or degrading talk, more often experience rumours that are of a sexual nature. This is also the case for threats: women more often experience threats of a sexual nature. For more information about gendered differences in terms of political violence experienced, please see the graph.

Gender aspects of political violence (GAPV)

In recent years, the election of greater numbers of women to office, a series of high-profile acts of violence against women politicians and emerging coalitions of women politicians and women’s groups at the national level and international organisations, have put additional focus on gendered political violence. The Inter-Parliamentary Union (2016) and the National Democratic Institute #NotThe Cost (2018) identified three defining characteristics of violence against women in politics (VaWiP): it targets women because of their gender, it takes a gendered form, and it has the purpose of discouraging or denying women the ability to participate equally in politics.

Sources and timing of political violence

Political party is a significant source of political violence. Nearly 71 percent of those who were subjected to degrading talk and false rumours say it was started by another party, while almost a third of respondents note the rumours originated within their own party. Women are more likely than men to experience political violence from within their own party.

Over half of respondents who reported being the subject of degrading talk or false rumours (52 percent) identify digital media as the source of that form of political violence.

With respect to threats, digital media and ‘other party’ are important sources – 39.7 and 38.5 percent respectively – but for nearly half of those who are subject to threats, it originates in the community.

In general, political violence is most likely to occur during an election campaign – of those who experienced destruction of property, 74 percent note it took place during this period, while 69 percent of those subjected to degrading talk or false rumours experienced this during an election campaign. Yet, for those who are elected, political violence is more likely to take place while in political office.

Party action

In a majority of cases, those who experienced political violence did not report it to their party. When it was reported, it usually related to physical violence. However, respondents who experienced violence and reported it to their party, indicate that action was taken less than half the time. Political parties most often take action when their members (candidates or elected politicians) are victims of threats.

Consequences of political violence

In general, politicians do not feel constrained in their public and political utterances as a result of political violence, but women were more likely than men to say that their political engagement made them more afraid. Women were also more likely than men to report having lower levels of political ambition (i.e. being less willing to run in the future). However, women who were elected were not more likely than their male counterparts to indicate opting out of politics. The number of respondents here is small, so this finding should be treated with caution, but it suggests that there may be a difference between elected and unelected women that should be probed further. Further research is needed to explore the implications of these results. It may indicate greater resilience among those currently in elected office. For women who are successful, they enjoy the fruits of the campaign – they get to participate in Dáil Éireann or their local council and contribute to policymaking. Those who lose have nothing to counterbalance the political violence experienced, so it is unsurprising that politics doesn’t seem worth the cost. However, since many candidates in Ireland run multiple times for different offices, the discouragement effect might have significant consequences and make it more difficult for parties to recruit women who have run before for future election campaigns.

Why does this matter?

While our study is rooted in the Irish experience, the findings are not unusual from a global perspective. International research points to the “devastating consequences for the quality of democracy” of political violence directed at politicians (Krook 2017), especially for women in politics. This includes its impact on sustaining women in politics and inhibiting the ambitions, motivation and mobilisation of new candidates. Research also highlights the intersectional nature of political violence, particularly that directed at women, with women of colour, young women and women from the LGBTQ+ community particular targets (see Collignon et al 2021). Given the increasing global evidence of the abuse, intimidation and harassment directed at politicians, questions have arisen about who would want to enter political life and who can withstand the level of abuse directed at political actors? Moreover, who ends up running for political office is important to consider, as they will have a significant bearing on future policy and political decisions. Thus, to ensure a diversity of people feel safe to participate in political life and a multiplicity of perspectives are brought to bear on policymaking, we need to acknowledge that political violence is happening, recognise its various forms and understand its differential consequences for women and men.

References

Ballington, J. (2003) ‘Gender equality in political party funding’, a paper presented at the Is financing an obstacle to the political participation of women workshop, Inter-American Forum on Political Parties, OAS, Washington DC. Available online at: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/speeches/Gender-Equality-in-Political-Party-Funding.pdf (accessed 27 September 2023).

Bardall, G; Bjarnegård, E. and Piscopo, J. M. (2020) ‘How is Political Violence Gendered? Disentangling Motives, Forms, and Impacts’, Political Studies, 68(4), 916–935.

Bjarnegård, E. (2018) ‘Making Gender Visible in Election Violence: Strategies for Data Collection’, Politics & Gender 14(4), 690-696.

Collignon, S; Campbell, R. and Rüdig, W. (2022) ‘The Gendered Harassment of Parliamentary Candidates in the UK’, The Political Quarterly, 93, 32-38.

Inter-Parliamentary Union (2016) Issues Brief: Sexism Harassment and Violence against Women Parliamentarians, Geneva. IPU. Available online at: https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/issue-briefs/2016-10/sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-parliamentarians (accessed 27 September 2023).

Krook, M.L. (2017) Violence against women in politics is rising – and it’s a clear threat to democracy. Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2017/08/12/violence-against-women-in-politics-is-rising-and-its-a-clear-threat-to-democracy/ (accessed 1 September 2023).

National Democratic Institute (NDI) (2018) ‘#NotTheCost: Stopping Violence Against Women in Politics’, submission by the National Democratic Institute to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women. Available online at: www.ndi.org/not-the-cost (accessed 1 September 2023).

Thames, F.C. and Williams, M.S. (2010) ‘Incentives for personal votes and women’s representation in legislatures’, Comparative Political Studies, 43(12), 1575–600.

Project Information

The results are from a survey conducted in Ireland as part of The Cost of Doing Politics: Gender Aspects of Political Violence project. The project is hosted by CMI and is funded by the Research Council of Norway. The Cost of Doing Politics project brings together an international research team to undertake a comprehensive, multi-method examination of if and how gender shapes political violence targeting politicians. The project investigates gender differences in the extent and type of political violence experienced by men and women, and the gendered consequences of violence against political actors across three different types of regimes: stable democracies (Norway and Ireland); a new democracy (Ghana); and an authoritarian system (Uganda).