Escaping Khartoum: Understanding forced displacement

The main drivers: Fear of violence and collapsed health and education services

Internet as a facilitator: Social media and communication apps

Networks and financial dependency

Mobility across borders: Legal pathways, refugee journeys, and the role of passport privilege

How to cite this publication:

Samahir Elmubarak (2025). Escaping Khartoum: Understanding forced displacement. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (Sudan Brief 2025:01)

The war in Sudan has triggered a mass displacement crisis. This brief examines the drivers and implications of forced migration, highlighting the urgent need for interventions to ensure safety and dignified mobility.

‘We were caught off guard by the loud sounds of bombs that were somewhat unfamiliar and terrifying …The source of the sounds was unknown creating confusion and fear…Private schools called the parents urging them to pick up their children, while the private sector companies dispatched buses to evacuate employees. Heavily armed military vehicles sped through the streets, and the scene in central Khartoum descended into a complete status of utter chaos and fear’. Abdulla, Male, 63 yrs, Interviewed on 24-02-2024.

On April 15, 2023, violent clashes broke out between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), soon escalating into a full-blown war. This brief is based on sixteen in-depth narrative interviews conducted with individuals who had to flee from Khartoum during the first year of the war. Abdulla is one of them. During the first week of war, he left Khartoum for his hometown in the White Nile State but soon after his house and company there were looted. Living conditions became unbearable, and he undertook a second journey from the White Nile State cross-country through the eastern border to Ethiopia, with Saudi Arabia as the final destination on a family visit visa. His experiences illustrate the trajectory of many of the 11.7 million Sudanese who are now displaced, either internally or in neighbouring countries.

The main drivers: Fear of violence and collapsed health and education services

A common thread through Abdulla and others’ stories is an increasing feeling of insecurity. As the war escalated, the lack of safety in Khartoum became a main driver of displacement. The respondents who hoped that the war would be short-lived realized that they were mistaken when their safety was compromised; others acted rapidly and relocated their families as soon as signs of RSF soldiers became visible in their neighborhoods. In many neighborhoods services, shops, and basic commodities became scarce.

Additionally, reports of sexual violence committed by RSF soldiers raised alarm, and the threat of gender-based violence drove families, particularly those with girls and women out of the city.

Reem is one of the women who was forced to flee along with her mother and sisters in the second month of the war, primarily because they feared getting raped by the RSF.

“Two days before we left, the RSF vehicles showed up on the main road, and some of them entered on foot into our neighborhood. …We were scared that something would happen, especially the gender-based attacks. We heard about attacks on girls and women, which was worrisome… The fear of rape and these types of violations are what made us leave. …This is what drove us out of our home.” Reem, Female, 32 yrs, Interviewed on 28-02-2024

Another crucial driver behind people’s decision to leave was the collapse of the health and educational sectors. Healthcare was severely disrupted by the war with more than 80% of the hospitals coming out of service. Families with chronically ill patients were forced out of Khartoum and as time progressed out of Sudan. It also caused many cases of preventable deaths such as in the case of Faisal’s aunt. Faisal is a 36-year-old male who moved with his aunt, a recovered cancer patient, to Aljazeera State for her to obtain medical care upon the discovery of the recurrence of her cancer in the second week of the war.

“The reason that I left Omdurman [Khartoum] was my aunt, who was a diagnosed cancer patient… her condition deteriorated, and her health got much worse, we went to a hospital, where we discovered the recurrence of cancer in a new area- her lungs. She was supposed to start chemotherapy immediately. We decided to travel immediately, the options were to choose a place that could be safe, where medicines and treatment could be available … After consultation and discussion with multiple acquaintances and medical professionals in the oncology field, we chose to go to Madani [Al Jazeera State].” Faisal, Male, 36 yrs, Interviewed on 20-02-2024.

The influx of IDPs into rural towns and villages strained already limited health services, causing waves of “multi-destination displacement” in search of areas with better healthcare infrastructure.

The war also had a significant impact on education as schools and universities remained closed indefinitely. The respondents with school-aged children chose to leave the country so their children could continue their education.

Hiba is a mother of two children, who in the first week of the war was displaced to her family’s hometown in Aljazeera State. A month later she returned to Khartoum to take her children to Egypt to catch up on the school year.

“This was a war. There were no schools and no chance that life was going to return to normal. I decided that for the kids and their education, I am going to travel to Cairo.” Hiba, Female, 39 yrs, Interviewed on 23-02-2024.

Education now more than ever has become a survival necessity to ensure better futures and in some cases better presents, as in some cases enrolling children in schools allow families to obtain residence permits in host countries.

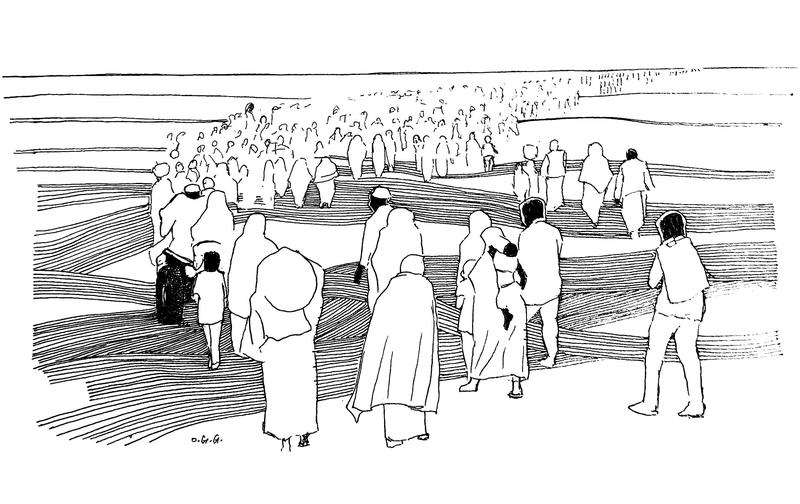

Initially, most respondents moved internally within Sudan due to their expectation that the conflict would be short-lived. Downplaying the duration of the conflict has influenced the initial decisions of the respondents, particularly in the choice of destinations and what they brought along. Most respondents were displaced internally during the first weeks of the war. They chose destinations they were already familiar with, often where members of their extended families lived. As the war expanded and their places of work and residence were destroyed, many started to reconsider and undertook a second cross-border journey, becoming part of the 3.1 million Sudanese that have left the country altogether.

Internet as a facilitator: Social media and communication apps

Social media and communication apps played a key role in keeping respondents informed and providing updates in real-time on safe routes and exits out of Khartoum. Many first learned about the war through Facebook, WhatsApp, and X (formerly Twitter) as in the case of the university graduate Mustafa.

“I went on Facebook and read that there was a movement of armed troops and others saying that they were hearing gunshots from the sports city, I went outside to verify if what people were posting on Facebook was real, and when I went out, I could hear gunshots.” Mustafa, Male, 25 yrs, interviewed on 28-02-2024.

These platforms helped the respondents manage challenges by facilitating connections with healthcare providers, assisting in the navigation of dangerous zones, and providing information about RSF checkpoints. It helped many families remain connected and eased their anxieties. The internet also facilitated financial transactions through banking applications as cash flow became both disrupted and dangerous. This was evident in Hala’s dependence on social media to overcome the everyday difficulties of being home with a bedridden father.

“I sent messages on Facebook asking if someone could help us find a doctor who could insert my father’s feeding tube. We found a doctor who happened to be in our neighborhood and coincidently it was the same doctor who had inserted it the first time [before the war].” Hala, Female, 30 yrs, Interviewed on 01-03-2024.

She also relied on Facebook to navigate the safest routes for her brother coming home.

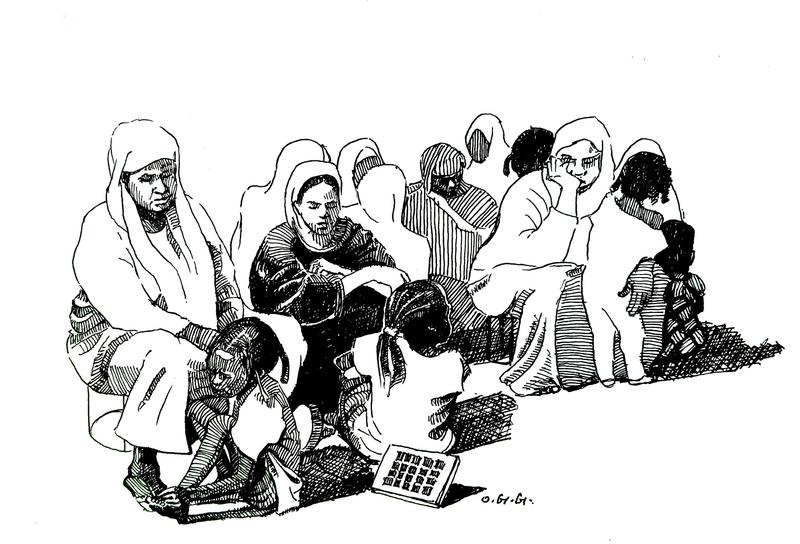

Networks and financial dependency

Many Sudanese citizens faced immense financial burdens due to displacement and loss of income, often relying heavily on family members abroad as savings were depleted, homes were looted, and income generation became challenging. The dependence on transnational networks continues and for many, the extreme hit to their financial independence has taken a toll on their pride and sense of autonomy. Nevertheless, those who had relatives in the diaspora were in a better situation than many others, even though there is a risk of the protracted dependency causing fatigue and overburdening among the diaspora.

Hiba did not only depend on savings for the initial part of her displacement journey. As she settled in Egypt and enrolled her children in schools, she continued to depend on money from relatives in the diaspora.

“The money that we have is finished. We are now dependent on the money that we get from abroad, from family. Even that is not enough, especially with the schools being expensive, the rent and the expenses, and the children's requirements.” Hiba, Female, 39 yrs, Interviewed on 23-02-2024.

Mobility across borders: Legal pathways, refugee journeys, and the role of passport privilege

The Sudanese who were able to leave on family visas, temporary visas, or tourist visas are not part of the statistics showing the number of displaced persons. They find themselves in a grey zone where they will remain until they can get their paperwork sorted out. For many who could afford to leave Sudan legally, Egypt was initially the preferred destination due to feasible visa requirements for women, children, and the elderly. However, as the war continued new visa restrictions were introduced making it difficult for many to cross borders. Other destinations the respondents mentioned included Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Uganda, and Rwanda seeking opportunities through existing networks or temporary visas.

As a result of countries’ different visa regimes, many families have been spread across multiple countries. The men have moved to for example South Sudan, Uganda, and Rwanda, because their gender has acted as the intervening factor rendering displacement to Egypt impossible.

Others have chosen to cross the border illegally, risking their lives along the way. In Egypt, asylum seekers faced difficulties reaching the UNHCR offices as they were in Cairo and not in cities near the border. Nasir left Khartoum with his family after the first month of war, to go to their hometown in the Northern State. Six months later with the war expanding to other states, in addition to the lack of health services and the narrowing down of visa options, Nasir and his parents and sisters entered Egypt by road through a human smuggling route to seek asylum there.

“We had the intention to apply for international protection, but there was no office for the UNHCR in Aswan, or anywhere close to the border, so we had to go to Cairo, we had no choice. Had there been an office closer to the border, we would not have had to take the risk of going all the way to Cairo to apply at the UNHCR offices.” Nasir, Male, 43 yrs, Interviewed on 15-02-2024.

People with dual citizenship or foreign passports had greater mobility options than individuals with Sudanese passports, who in turn were more privileged than those who did not have passports at all. Despite the chaotic conditions, having a foreign passport made crossing borders possible, and the experiences of Shahd, a Sudanese-British citizen stood in sharp contrast with others in her family who did not benefit from the same freedom of movement.

“A day later, together with my grandma and my aunt, we were like, you know, we have British passports we can figure it out not like into you, so it does not get worse and more difficult to leave, you need to make a move. They decided to move and went to Cairo. They have Sudanese passports, and we had a feeling that it was going to get worse, and more difficult for Sudanese citizens.” Shahd, Female, 24 yrs, Interviewed on 27-02-2024.

Conclusion

The ongoing war and the forced displacement have deeply impacted Sudan’s social fabric. Factors like gender, age, education, and socioeconomic status influence how an individual experiences and navigates displacement. However, some elements show up repeatedly in the displaced persons’ accounts of their journeys, such as the fear of violence and challenges regarding visas. Despite Sudan being the biggest displacement crisis the world has seen, there is a lack of safe migration pathways and little access to basic health and education services. Although the chronic underfunding to the Sudan crisis is an obvious obstacle, there are concrete steps that can be made. For example, the UNHCR could set up more offices at border points and strengthen the capacity of existing offices. Multilateral efforts could also be made to open consulates or service offices in Port Sudan and to facilitate visa processing. Such measures must of course come in addition to the immediate actions necessary to address the root causes of forced displacement and during an on-going war to fulfill the obligation to protect civilians.

This brief is an output from the Sudan-Norway Academic Cooperation. It is based on Samahir Elmubarak’s master’s thesis ‘Narratives Behind Numbers – A Narrative Research on Forced Displacement from the State of Khartoum During the First Year of War in Sudan’, submitted at Lund University’s International Master Programme in International Development and Management (LUMID).

References/Further reading

ACLED 2024, Sudan Situation Update: April 2024 | One Year of War in Sudan, ACLED.

Bastia, T 2014, ‘Intersectionality, Migration and Development’, Progress in Development Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 237–248.

Castles, S 2003, ‘The International Politics of Forced Migration’, Development, vol. 46, no. 3.

Haug, S 2008, ‘Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 585–605.

Hydén, G 2015, ‘The Economy of Affection’, in Routledge Handbook of African Politics, Routledge, London, pp. 334–345.

Koser , K & Martin, S 2011, The Migration-Displacement Nexus, The Migration-Displacement Nexus Patterns, Processes, and Policies, Berghahn Books, United States of America, pp. 1–13.

Lischer, SK 2007, ‘Causes and Consequences of Conflict-Induced Displacement’, Civil Wars, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 142–155.

Saltsman, A & Majidi, N 2021, ‘Storytelling in Research with Refugees: on the Promise and Politics of Audibility and Visibility in Participatory Research in Contexts of Forced Migration’, Journal of Refugee Studies, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 2522–2538.

OCHA 2024, Sudan Humanitarian Update (1 - 30 November 2024)