An Elusive Fiscal Social Contract: Three Lessons from South Africa

Lessons from the Western-European history of taxation and fiscal social contracts

South Africa an exceptional case

High taxes, yet weak governance and socially unproductive public expenditure

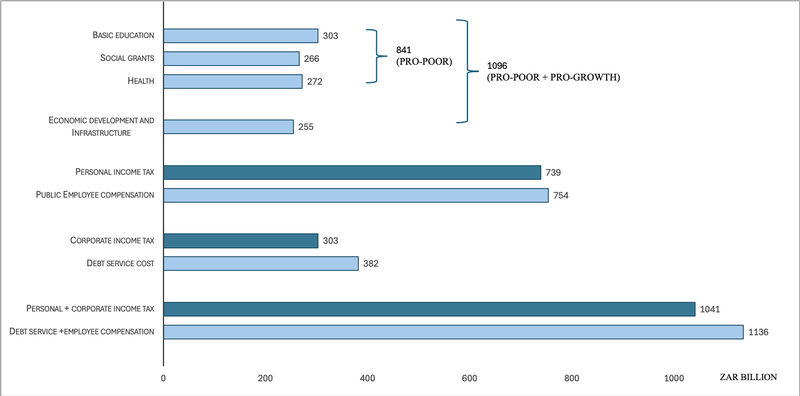

Figure 1 Pro-poor and pro-growth expenditure deprioritized in revenue allocation

Conditions favoring a fiscal social contract

Why has South Africa failed to develop a fiscal social contract?

How to cite this publication:

Sansia Blackmore and Odd-Helge Fjeldstad (2025). An Elusive Fiscal Social Contract: Three Lessons from South Africa. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2025:03)

Introduction

A common policy concern in developing countries is that inadequate government revenue hampers development. Hence, many countries focus on raising revenue through taxation, assuming governance improvements will follow because taxpayers will demand something in return for their tax payments, i.e. constituting a “fiscal social contract” between taxpayers and the government. Post-Apartheid South Africa has achieved remarkable success in revenue collection. However, despite high tax collection, governance and social indicators have declined. This policy insight explores three possible reasons why a fiscal social contract has not materialized in South Africa. We argue that (1) excessive coercion by the revenue administration undermines voluntary tax compliance; (2) fiscal bargaining is unlikely in a highly unequal society relying on a very narrow base; and (3) unlike in transactional settings, norms-driven societies require different triggers for fiscal accountability.

Lessons from the Western-European history of taxation and fiscal social contracts

The history of state-building in high-tax Western countries offers evidence that mobilizing domestic financial resources through the tax system is associated with improved governance (Levi, 1988; Tilly, 1990). The positive tax-governance link developed along three channels (Moore, 2015). First, taxation strengthens state capacity because dependency on taxes compels states to develop a competent bureaucratic apparatus for tax collection. Second, governments have stronger incentives to promote economic growth when they are dependent on taxes and therefore on the prosperity of taxpayers, which aligns the economic interests of a state and its citizens. Third, taxation may foster reciprocal bargaining between taxpayers and the state. The reciprocal nature of taxes offers taxpaying citizens leverage to bargain with the state: (quasi-) voluntary tax compliance in exchange for socially beneficial and accountable use of their taxes. In Western Europe, negotiations between states and citizens over taxes were intertwined with the emergence of participatory politics and also central to the development of productive fiscal social contracts.[1]

South Africa an exceptional case

South Africa, historically the largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa, democratized in 1994. A new constitution in 1996 institutionalized human rights and mechanisms of political accountability. Fiscal policy was a key instrument in the effort to address the inequality resulting from the economic and social exclusion of black South Africans during Apartheid. The fiscal mechanism was intended to accelerate transformation towards a just and inclusive society (Levy, Hirsch, Naidoo and Nxele, 2021).

Yet, after three decades of democracy, unemployment and inequality remain among the highest globally. Economic stagnation and state-induced infrastructure failures have exacerbated poverty (Hausmann, 2023). Growth has stagnated below one percent for the last decade. Poverty is pervasive; approximately 28 million out of a population of 62 million subsist on tax-funded monthly cash grants with a weighted average value below the Food Poverty Line of ZAR 796 (approx. USD 42). Despite this, tax collection remains high at 25–28% of GDP, comparable to Switzerland and Australia (OECD, 2024). The largest collection comes from personal income tax that is concentrated on a small number of individuals (11 percent of the population). This small tax base continues to narrow and limits broad-based fiscal engagement.[2]

High taxes, yet weak governance and socially unproductive public expenditure

South Africa’s tax system resembles that of well-governed OECD countries, yet its governance standards lag behind even many of its low-taxing African peers. Despite tax collection between 25 and 28 percent of GDP, South Africa receives a negative score in the Control of Corruption pillar of the World Bank's governance indicators. This is unusual for a country with a tax-to-GDP ratio like South Africa’s. Most high taxing countries typically receive positive and much better governance ratings. Even neighbouring country Botswana has a positive governance score well above that of South Africa, although it only collects 15 percent of its GDP in taxes. Successful and significant tax collection has therefore not produced the governance dividend that would help shape a fiscal social contract in South Africa in a manner that is consistent with the Western European experiences.

The weaknesses in governance were not foreseeable during the optimistic early years of democracy given how firmly provision was made for institutional checking mechanisms and constraints on the executive in the Constitution of 1996 (Levy et al., 2021). State capture,[3] which became entrenched and gained momentum during the presidency of Jacob Zuma (2009-2017),[4] led to pro-elite diversion of public funds (GoSA, 2022). Taxes ceased to serve the needs of a society in need of huge public investments in social and economic transformation.

Figure 1 shows that in 2024, for instance, ZAR 266 billion was budgeted for social grants for 28 million people, while public employee compensation reached ZAR 754 billion—exceeding the total personal income tax revenue (the largest source of tax revenue). Rising debt-service costs further limit developmental spending. Debt servicing and employee compensation absorb more than half of total taxes collected and exceed total direct tax collections. Corruption and cadre deployment have eroded service delivery, leaving basic services, such as drinking water and electricity, unreliable.

Figure 1 Pro-poor and pro-growth expenditure deprioritized in revenue allocation

Conditions favoring a fiscal social contract

Much like bargaining between states and citizens produced participatory citizenship in Western Europe, a fiscal social contract is forged when citizens have both the capacity (in terms of bargaining power) and the proclivity (in terms of social norms) to negotiate with governments over taxation (Prichard, 2015).[5]

One of the conditions that would support the emergence of a fiscal social contract is when taxes contribute significantly to state revenue, which in theory strengthens the bargaining power of taxpayers (Levi, 1988; Braütigam, Fjeldstad and Moore, 2008; Moore, Prichard and Fjeldstad, 2018). Second, taxes that are salient, such as personal income tax, heighten taxpayers’ awareness of their contribution and are more likely to encourage demands for engagement and accountability with regard to the spending of revenue (Persson, Fjeldstad and Sjursen, 2025). Third, taxes that are broad based affect more taxpayers and mobilization around such taxes is bound to exert more leverage (Prichard, 2015). Fourth, salience in public expenditure also influences taxpayers’ perception of reciprocity (Doerrenberg, 2015). Expenditures that visibly violate reciprocity are more likely to invite taxpayer contestation. Fifth, the institutional setting matters. A fiscal social contract is unlikely to emerge in an authoritarian institutional environment that favours coercive enforcement and minimal taxpayer rights (Levi, 1988; Tayler, 2006).

Additionally, social values influence civic engagement by shaping citizens’ expectations from government and how forceful they are in their demands (Ali, Fjeldstad and Sjursen, 2014). Thus, social values can be a defining feature of the nature of the social contract in a particular context. In transactional societies, taxpayers demand direct returns, while norms-driven societies comply based on moral obligation, often tolerating misgovernance longer. The World Values Survey and the Afrobarometer Survey are helpful to indicate whether a country's social values are consistent with a norms-driven or with a transactional social contract.

In norms-driven societies, tax compliance is largely unconditional and taxes are not typically leveraged when citizens attempt to bargain with the state for greater accountability (Bak, 2019). Rather, taxpayers comply with tax obligations based on a moral conviction of what is right. Although tax resistance may not be a typical mode of civic objection in norms-based societies, it may emerge when citizens’ sense of morality becomes outraged. In a transactional social contract, taxpayers are more likely to demand a direct quid pro quo for their taxes and tax compliance is conditional on taxpayer expectations being met. Tax bargaining is more likely to ensue when lapses in accountability and governance become apparent and hence a productive fiscal social contract may emerge more readily in a transactional social setting.

Why has South Africa failed to develop a fiscal social contract?

Favourable features that may support the emergence of a fiscal social contract are that South Africa is a fiscal state and is reliant on tax for 98 percent of state revenue; the bulk of revenue is collected from salient direct taxes; the use and misuse of taxes are both salient; and, in theory at least, the institutional checking mechanisms exist. However, outweighing these factors, are a number of context-specific disqualifying factors.

The first refers to coercive tax administration. The Tax Administration Act (TAA) 28 of 2011 allows stringent enforcement that is more coercive than one would expect in a democracy with protection of taxpayer rights. Initially this was justified to fund transformation. However, it facilitated state capture rather than public benefit. It is the duty of the judiciary to enforce legislation. Hence, when taxpayer objections to the diversion of tax revenue (especially on municipal level) culminated in litigation, the court system enforced tax laws, leaving taxpayers without institutional recourse in the face of public-service failures. Recently, however, High Court rulings appear to have adjusted the scale to offer more protection for taxpayer rights.[6] This may create the beginnings of an institutional platform for tax barganing that previously did not exist.

The second relates to the narrow tax base and inequality. Personal income tax is highly progressive, but narrowly concentrated on 7.4 million individuals. One-third of personal income tax comes from 200,000 individuals. These taxpayers lack the numbers to mobilize for tax bargaining. The rules are too strict[7] and their numbers too few. Meanwhile, 28 million grants are paid out monthly to vulnerable citizens who out of necessity may have to tolerate clientelistic forms of accountability. Through lack of alternatives, they are forced to be co-opted into a system that perpetuates their vulnerability and state dependence and would not mobilize for greater accountability. Through these distortive effects, inequality dominates fiscal relationships between the state and taxpayers, and also the state and grant recipients, significantly lowering realistic prospects for tax bargaining.

Third, country reponses to specific questions in the Afrobarometer Survey (2024) suggest that South Africans adhere to a norms-driven contract, reducing tax resistance despite misgovernance.[8] A combination of a norms-driven social contract and the distortive inequality effects may explain the ANC’s prolonged electoral dominance despite social and economic decline.[9] The national election in 2024 eventually saw the liberation party lose its outright majority and having to share power in a Government of National Unity (GNU) with among other parties the Democratic Alliance (DA), the erstwhile official opposition party in Parliament.[10] The unsustainable fiscal dynamics of the past 15 years finally culminated in a political impasse during the budget season in February/March 2025. A budget proposal to raise value-added tax by two percentage points from 15 percent to 17 percent was rejected by the GNU partners, creating a deadlock on passing the budget through Parliament. The proposal, which would impose a regressive tax on the poor to fund yet another above-inflation salary increase for a well-remunerated yet ineffective bureaucracy, provoked widespread condemnation. It appears that the broad-based nature of the tax proposal coupled with the moral outrage citizens experience over the hardship imposed by corrupt governance has sparked nation-wide objection and resistance. Being unable to force yet another tax increase through Parliament as in the past, places the ANC and its alliance partners in unfamiliar fiscal territory. It may signal the tender beginnings of tax bargaining from which a fiscal social contract may be forged.

Conclusion

South Africa’s post-apartheid fiscal experience cautions that a singular focus on revenue mobilization to pursue development without ensuring reciprocal governance, may produce perverse fiscal outcomes. Three key lessons emerge:

- Excessive coercion undermines voluntary tax compliance. Building institutional frameworks for effective revenue collection is essential, but overdoing coercive enforcement undermines the development of an environment that would cultivate voluntary compliance. Overly coercive collection, as seen in South Africa, may instead fund corrupt activities at high cost to society.

- Inequality limits fiscal bargaining. While progressive taxation is essential in unequal societies, a narrow tax base weakens taxpayers’ leverage. Personal income taxes are typically used to facilitate transfer of income. Personal income taxes are also the salient kind of tax most likely to spur tax bargaining. Yet, the prospects of tax bargaining depend on the bargaining power that taxpayers may leverage. Narrow-based taxes simply do not offer the necessary leverage. Hence, as we observed in South Africa tax bargaining is unlikely in an unequal context relying on a very narrow base for personal income tax. Furthermore, if a large share of the population relies on state-funded social protection, this dependence may dominate their fiscal exchange, which is then characterised by tolerance for unaccountable governance in exchange for promises of a continuation of state assistance.

- Norms-driven societies require different triggers for fiscal accountability. Unlike in transactional settings, tax resistance in norms-driven societies emerges from moral outrage with taxes that are diverted and have ceased to serve the collective interest of society rather than from direct reciprocity concerns. Thus, tax objections may eventually emerge in non-transactional contexts. Although slower to emerge, norms-driven fiscal social contracts can be cultivated too. The recent rejection in Parliament of the VAT hike signals a potential shift towards tax bargaining and a future fiscal social contract.

Literature

Afrobarometer. (2024), Summary of results. Afrobarometer Round 9 Survey in South Africa, 2022. Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

Ali, M., Fjeldstad, O.-H., and Sjursen, I. H. (2014), To Pay or Not to Pay? Citizens’ Attitudes Toward Taxation in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and South Africa. World Development, 64: 828-842.

Bak, A.K. (2019), When the Fiscal Social Contract is not about Tax: Understanding the Limited Role of Taxation in Social Accountability in Senegal. PhD Dissertation, Aarhus University.

Besley, T. (2020), State Capacity, Reciprocity, and the Social Contract. Econometrica, 88(4): 1307-1335.

Blackmore, S. and Fjeldstad, O.-H. (2025), Taxation and governance in post-apartheid South Africa: Prospects for a fiscal social contract. CMI Working Paper WP 1: 2025. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Braütigam, D., Fjeldstad, O.-H. and Moore, M. (2008), Taxation and State Building in Developing Countries: Capacity and Consent. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Doerrenberg, P. (2015), Does the Use of Tax Revenue Matter for Tax Compliance Behavior? Economics Letters, 128: 30-34.

Fritz, C. (2017), An Appraisal of Selected Tax-Enforcement Powers of the South African Revenue Service in the South African Constitutional Context. Unpublished LLD thesis, University of Pretoria. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/62233.

Gethin, A. (2020), Extreme Inequality and the Structure of Political Cleavages in South Africa, 1994-2019. Paris: World Inequality Lab, Paris School of Economics. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03022282

Government of South Africa [GoSA]. (2022), Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including organs of state ("Zondo Commission").https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202203/judicial-commission-inquiry-state-capture-reportpart-3-ivsss.pdf.

Hausmann, R., O’Brien, T., Fortunato, A., Lochmann, A., Shah, K., Venturi, L., Enciso-Valdivia, S., Vashkinskaya, E., Ahuja, K., Klinger, B., Sturzenegger F. and Tokman, M. (2023), Growth Through Inclusion in South Africa. CID Faculty Working Paper No. 434.

Hellman, J.S., Jones, G. and Kaufmann, D. (2000), Seize the State, Seize the Day: State Capture, Corruption, and Influence in Transition. Policy Research Working Paper 2444. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Levi, M. (1988), Of Rule and Revenue. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Levy, B., Hirsch, A., Naidoo, V. and Nxele, M. (2021), When Strong Institutions and Massive Inequalities Collide. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Meagher, K. (2018), Taxing Times: Taxation, Divided Societies and the Informal Economy in Northern Nigeria. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(1): 1-17.

Moore, M. (2015), Tax and the Governance Dividend. ICTD Working Paper 37, July 2015. Brighton: International Centre for Tax and Development.

Moore, M., Prichard, W. and Fjeldstad, O.-H., (2018), Taxing Africa: Coercion, Reform and Development. London/New York: African Arguments Book Series, Zed Books.

Moosa, F. (2017), The 1996 Constitution and the Tax Administration Act 28 of 2011: Balancing efficient and effective tax administration with taxpayers' rights. Unpublished LLD thesis, University of the Western Cape. http://hdl.handle.net/11394/5532.

National Treasury. (2009 to 2024), Budget Review. Pretoria: Government of South Africa. OECD, African Union and African Tax Administration Forum. (2024), Revenue Statistics in Africa 2024. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/c511aa1e-en-fr

Persson, A., Fjeldstad, O.-H. and Sjursen, I.H. (2025), Taxing for a Social Contract in Sub-Saharan Africa. CMI Working Paper (forthcoming). Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Prichard, W. (2015), Taxation, Responsiveness and Accountability in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Dynamics of Tax Bargaining. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, J. A. (2023), Tax Aversion and the Social Contract in Africa. Journal of African Economies, 32: 33- 56.

Tayler, T. (2006), Psychological Perspectives on Legitimacy and Legitimation, Annual Review of Psychology, 57: 375-400.

Tilly, C. (1990), Coercion, Capital, and European States: AD 990-1990. Cambridge: Blackwell. World Bank. World Governance Indicators Databank. Accessed February 2025. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Notes

[1] The concept of the social contract has its origins in the work of a range of influential philosophers, such as Plato (c. 375 BC), Hobbes (1651), Locke (1690), Rousseau (1762), and Kant (1797). They argued that ‘civil and political rights constitute a form of exchange where a citizen accepts obligations in return for benevolent government’ (Besley, 2020: 1309). Such a contractarian perspective allocates a central role to reciprocal obligations in establishing an effective state in which the power to tax is as fundamental (Levi, 1988) as the state’s monopoly on violence. The idea of a fiscal social contract expresses the notion that fiscal state-society bargaining and exchanges produce socially beneficial outcomes such as political representation, state-building, and responsive and accountable governance.

[2] According to the South African Revenue Service’s annual tax statistics for 2024, 37 584 citizens have ended their tax residency in South Africa during 2023 resulting in a loss of ZAR 3 billion in collectable taxes for the 2023/24 tax year. Over the ten years from 2014 to 2023, a total of 432 848 taxpayers have terminated their South African tax residency either through emigration or changing their tax status. The trend is prevalent among high-income taxpayers; in 2023 for instance 2 380 taxpayers earning more than ZAR 1 million per year ended their tax residency.

[3] State capture refers to the way formal procedures such as law and policy making, and government bureaucracy are manipulated by government officials, state-backed companies, and private companies or individuals, to influence state policies and laws in their favour (Hellman et al., 2000).

[4] Jacob Zuma served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018 and president of the governing party, the African National Congress (ANC), from 2007 to 2017. His presidency was beset by controversy and mismanagement. By early 2016, there were widespread allegations, later investigated and confirmed by the Zondo Commission (2018–2022), that the Indian Gupta family had acquired immense influence over Zuma’s administration, amounting to state capture characterised by systemic political corruption in which the Gupta’s private interests significantly influenced the state’s decision-making processes.

[5] A growing body of literature explores why fiscal social contracts remain elusive in developing countries (Meagher, 2018; Bak, 2019; Robinson, 2023).

[6] In December 2024, the High Court delivered a landmark ruling with regard to SARS’s interpretation and use of the TAA. Ruling against SARS with a punitive cost order in ASPASA NPC and other v C:SARS, the court noted that statements by SARS were “intemperate, disproportionate, and reflective of an inappropriate hostility toward taxpayers”. The court further noted that SARS “adopted a hostile and contradictory stance” in opposing the applicants’ reasonable and lawful application and acted in a manner “not befitting of a public authority tasked with administering the tax law fairly and respectfully”.

[7] For instance, sections 45(1), (2), 63(1) and (4) of the TAA authorize SARS to conduct warrantless inspections and searches, limiting taxpayers’ rights to privacy. Sections 45(1) and (2) may in fact be unconstitutional (Fritz, 2017; Moosa, 2017).

[8] For a detailed discussion, see Blackmore and Fjeldstad (2025).

[9] A study on Extreme Inequality and the Structure of Political Cleavages in South Africa, 1994-2019 (Gethin, 2020) uses data from the South African Social Attitudes Surveys (SASAS) to report that ‘the poorer, Black population have kept their support for the government broadly unchanged’ (p. 18 ) and that ‘opposition parties from across the political spectrum have been incapable of mobilizing low-income, low-educated citizens’ (p. 23).

[10] The seventh national election held on 29 May 2024 produced a result that may appear to signal voters’ willingness to mete out electoral sanction for poor governance, with support for the ruling ANC dipping sharply to 40 percent, down from 62 percent in 2014 and 57.5 percent in 2019.