What causes Latin America’s high incidence of adolescent pregnancy?

How to cite this publication:

Camila Gianella, Marta Rodriguez de Assis Machado, Angelica Peñas Defago (2017). What causes Latin America’s high incidence of adolescent pregnancy? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 9)

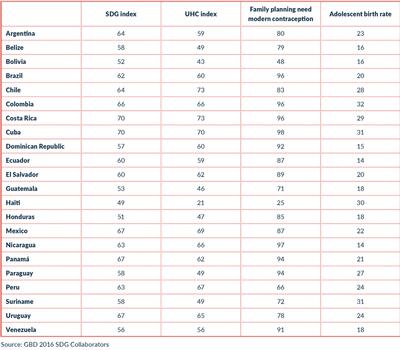

Latin America is the only region in the world where adolescent pregnancies are not decreasing. According to a recent article in the Lancet, if the current trend continues, Latin American countries will not fulfill the sustainable development goal on adolescent pregnancy by 2030. This underperformance has happened despite positive developments towards meeting family planning needs and universal health coverage goals (see Table 1). This brief demonstrates how conservative political mobilization has blocked gender education in Latin American schools.

Table 1: Latin American countries projected performance by 2030 on selected SDG indicators

Conservative mobilization through “gender ideology”

The blockage of gender education in Latin American schools can have dramatic effects on the health and life projects of young people, especially on young women. The recent wave of blockages of initiatives designed to introduce gender related content in school curriculums shows that policies are not only decided based on scientific evidence. Despite research evidence of the critical role played by sex education and gender equality in preventing adolescent pregnancy, the implementation of such programs is challenged by conservative mobilization. This opposition has been especially heated in the last decade. The debates around educational plans and gender-related public policies have been framed as a fight against “gender ideology”.

The use of “gender ideology” to discredit attempts towards gender equality is not a new phenomenon. During the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo (ICPD) in 1994 and the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995, the Holy See strategically used gender ideology to present gender as a model imposed by liberals against the traditional family. Gender was portrayed as an artificial definition originating from “savage capitalism”, which aimed to destroy the traditional family. The Catholic hierarchy and its allies denounced movements, like the feminist and LGBTI movements, arguing that they undermine family values and threaten the moral fabric of society.

The gender ideology framing has been invigorated by the massive wave of self-nominated pro-life and pro-family mobilization that has swept Latin America over the last two decades. This new wave of conservative mobilization builds on the traditional political role that was previously mainly played by Catholic Church in the region. Although the Catholic Church is still recognized as an important pro-life and pro-family leader, new actors and new mobilization structures have emerged.

Regressive policies and abortion bans

The rise of the conservative Evangelical churches throughout the region have expanded the coalition of anti-abortion actors. Civil society actors – like professional associations, bioethics groups and pro-life and pro-family NGOs – have inspired massive rallies and public campaigns. Conservative movements have an important, sometimes dominant, presence in the legislature of their respective countries which explains the regressive role Latin-American parliaments play in all sexual and reproductive rights and minority rights. Conservatives can block changes, approve regressive bills, and pressure the executive branches to withdraw the gender equality agenda. In Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, and Peru, where there is a high level of polarization between voters and political adversaries and presidents are elected on second rounds by slight margins of votes, religious conservative actors negotiate directly with the executive. From Mexico to Argentina, abortion rights in the region have gained remarkable saliency and traction in political campaigns and party policies.

In El Salvador and Nicaragua, a total ban on abortion has been approved. In these countries, the anti-abortion movement mobilized hundreds of thousands of protesters in marches supporting absolute abortion bans, created alliances with media, civil society, and professional organizations, and successfully generated new restrictions on abortion rights—restrictions that have negatively affected the health and freedom of the region’s most marginalized women.

Brazil is another example of this new alliance. The national movement, Brazil without Abortion (Movimento Nacional da Cidadania pela Vida – Brasil sem Aborto), founded in 2006, unites local pro-life and pro-family associations and mobilizes annual national marches and pervasive public campaigns. They have a direct connection with the parliamentary pro-life and pro-family caucus, also founded in 2006. Since its creation, the caucus has gradually increased its political power in Congress. In the last decade, sexual and reproductive rights and gender equality issues have experienced threats and kickbacks both in the legislative and the executive spheres.

The movement has also demonstrated remarkable national and transnational organizational capacity across the region. International pro-life organizations – like Human Life International – have influenced and mobilized expertise to local organizations across the region. It is also remarkable how strategies can be adapted to different national contexts.

The political battles in the Ministries of Education

In 2015, 2016 and 2017, Ministers of Education in Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay and Peru faced strong opposition from conservative groups. In Peru, conservative organizations won a court case against the inclusion of a gender sensitive approach in the school curriculum (Expediente N 00011-2017-0-1801-SP-CI-01), and supported the Parliament’s removal of two Education Ministries. In 2017, Uruguay has been experiencing strong opposition to the the proposal elaborated by the Uruguayan National Council of pre-school and primary education to include comprehensive sexual education at schools. Conservative groups as “A Mis Hijos No Los Tocan” (do not touch my children) have been behind this mobilization.

In 2016 in Colombia, during the negotiations of the Peace Agreement between the government and The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the gender ideology frame was actively used as a weapon to gain votes against this agreement. Gender ideology was used by conservative actors to reject the inclusion in the peace agreement of: ”the elimination of all forms of discrimination, valuing women as political subjects.” It sought to combat discrimination ”including those based on gender and sexual orientation and diverse gender identity” and to clarify ”the impact of conflict on children and adolescents and gender-based violence”. After the referendum where the Peace agreement was rejected, the Minister of Education, Gina Parody resigned. She paid the political price for defending the peace agreement and the gender sensitive approach.

In Brazil, in 2011, school material prepared by the Ministry of Education promoting diversity in schools, was recalled after strong pressure from conservative movements, Evangelical and Catholic leaders. The material “Schools without Homophobia” (maliciously termed “Gay Kit” by the opposition), was denounced as an instrument to promote homosexuality among children and destroy families. Since then, the fight to eliminate gender sensitive language and sex education from the national plans of education has intensified. In 2014, conservative congressmen edited the Brazilian National Plan of Education and removed the clause that stated that one of the goals of the public educational system is ”the overtake of educational inequalities, with emphasis on the promotion of racial, regional, gender and sexual orientation equality”. The same counter-mobilization took place at the state and municipality level. The case eventually reached the Brazilian Supreme Court in a polemic judgement in which religious teaching in public schools was authorized. In 2014, a movement called “A school without a party” proposed a bill of laws advocating for the ban of sexual education and critical views of history and social sciences in schools, which they frame as “gender ideology” and “ideological indoctrination”. Since 2014, at least 62 bills of laws based on the “right to conscious” and “religious freedom” of families were proposed in the Congress and State Legislative Houses. Brazil is just one example of a cross-regional wave of protests against sexual education and gender equality in school’s curricula that has been successful in influencing public educational policies.

Table 2: Legal actions against sexual education laws/programs in Latin America

Towards a better understanding of political determinants of health

Most countries in Latin America have already experienced setbacks in rights and significant cutting in gender related public policies. Understanding the political determinants of health, such as the new wave of conservative mobilization, is necessary to evaluate their impacts on women’s and adolescents’ most basic human rights. This requires a fuller understanding of the backlash against sexual and reproductive rights experienced in the region in the last few years. Regressive legislation has been approved in some countries. The enforcement of a criminal law on abortion in countries like El Salvador or Mexico has generated perverse outcomes for vulnerable women. Women are now forced to carry to term and give birth to fetuses that have no chance of survival outside the womb. However, as this analysis shows, abortion has not been the only field of dispute, education policy has been a contested field where conservative mobilization has won major victories by blocking the introduction of gender sensitive approach in many countries.

The adolescent fertility rate in Latin America (73,2 per 1000) is very high when compared to the worldwide rate of 48,9 and the rate in developing countries of 52,7 %. It is urgent that governments implement measures to guarantee girls and adolescents’ reproductive autonomy, access to information and empowerment. In this context, the new wave of conservative mobilization in Latin America must be taken seriously by those interested in preventing and reducing female poverty, and in promoting gender equality not only in Latin America, but worldwide. If there is something to be learnt from Latin America, it is that the battle against gender equality can be usefully used by political groups aimed to gain or to show political power.

References

Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, et al. Measuring progress and projecting attainment on the basis of past trends of the health-related Sustainable Development Goals in 188 countries: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 2017; 390(10100): 1423-59.

Loaiza E, Liang M. Adolescent Pregnancy: A Review of the Evidence. New York: UNPA, 2013.

Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Phillips-Howard P, Hunter PR. School-based sex education is associated with reduced risky sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in young adults. Public Health; 127(1): 53-7.

Córdova Pozo K, Chandra-Mouli V, Decat P, et al. Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Latin America: reflections from an International Congress. Reproductive Health 2015; 12(1): 11.

This publication is part of the UiB–CMI project Sexual and Reproductive Rights Lawfare: Global battles financed by the Norwegian Research Council.