Humanitarian borders: The merging of rescue with security and control

How to cite this publication:

Antonio De Lauri (2018). Humanitarian borders: The merging of rescue with security and control. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2018:11)

In the past few years, mass-media and political actors, especially emergent populist and right-wing political movements, effectively enhanced sentiments of panic and fear nourished by the idea that there is a severe crisis of borders in Western democracies. States’ inability to manage the flows of migrants and refugees has exacerbated security policies. The narrative of crisis has ideologically and politically justified the affirmation of humanitarian borders as zones where practices of aid and rescue merge with policing and rejection. The 2015 “migration crisis”, for example, did not only make explicit the dysfunctionality of Europe’s asylum system and its broader architecture, but it also made evident how politics of emergency and rejection increasingly undermine migrants safety.

States’ inability to manage the flows of migrants and refugees has exacerbated security policies.

We owe the definition of humanitarian border to William Walters (“Foucault and Frontiers: Notes on the Birth of the Humanitarian Border”, 2011) who explained that the idea of a humanitarian border might in itself sound like a contradiction. Contemporary humanitarianism is often described as a force that, in the name of an endangered humanity, transcends the walled space of both national and international systems. However, it would be misleading, Walters suggests, to draw any simple equation between humanitarian projects and logics of deterritorialization. While humanitarian interventions might stress certain norms of statehood, it is important to recognize that the exercise of humanitarian power is intrinsically connected to the production of new spaces. By redefining certain territories as “humanitarian zones”, humanitarianism actualizes a new geography of space in conflict areas, in regions affected by famine, in the context of failed or fragile states, and in situations where state borders and gateways to national territories become zones of humanitarian government. This is the case of a number of borders in Europe, the United States, the Middle East and Africa today. In Europe, for instance, the multiplication of border barriers, detention centers, and shelters, on the one hand, and the intensification of border patrol, maritime control, and deportations, on the other hand, signal a new step in European border history: the humanitarization of Europe, the creation of European borders as humanitarian zones affected by severe crisis.

With the rise of humanitarian borders, border politics have increasingly overlapped with practices of confinement (helping refugees and migrants at “home”). As a consequence, the externalization of European borders and policies of rejection have been framed as actions of compassionate control and as a response to crisis and insecurity. Patrolling coasts, expanding the reach of immigrant reception centers and fencing territories have thus become humanitarian reactions to migrant and refugee emergencies and, by extension, to a border crisis. Today, the mutual relationship between humanitarian search and rescue operations and state-sovereign performances on European borders reproduces, on European territory, a dynamic that humanitarian militarism around the world has best embodied for decades: the overlapping of rescue and global policing. Despite the diversity of geographical, historical and cultural contexts characterizing today’s humanitarian borders globally, it is possible to identify a transnational impetus of compassionate border security that fuses the humanitarian ethos with policing and militarization.

The power of crisis

One thing that is not often discussed in public discourses about control of mobility and the humanitarization of borders, is that crisis is good business for governmental, international and private actors that provide security infrastructures and personnel. The technological, bureaucratic and policing apparatuses that security regimes mobilize, produce a major and growing industry of our time. While the enforcement and supply of security has always been understood as one of the exclusive functions of the nation-state, recent developments, from the “war on terror” to the “migration crisis”, have triggered a process of internationalization and privatization of security. Rather than marginalizing the state, however, this process has accompanied the re-emergence of nation-state ideologies as an integral part of the globalizing effects of securitization.

The more crises we are exposed to, the more complex security architectures emerge from state, international and private actors. Indeed, crisis constitutes the lifeblood of the humanitarian system. Arguably, there is no humanitarianism without crisis. Of course, even if today’s humanitarian goals at the border might contribute to inequality and the reproduction of crisis, we might be inclined to distinguish between state actors, humanitarians and activists – not least to avoid blaming all humanitarians and activists to contribute to exclusion and death.

The more crises we are exposed to, the more complex security architectures emerge from state, international and private actors.

However, although this distinction is worthy of attention and certainly evokes a different ethos embodied by state actors and humanitarian organizations (that are themselves increasingly criminalized), border policing and humanitarian rescue belong to the same order of meaning to the extent that they take place in a humanitarian space governed by exceptionalism and emergency. It is in the framework of this contingent geography of crisis that we can understand the affirmation of regimes of protection and the dismantling of freedom of movement.

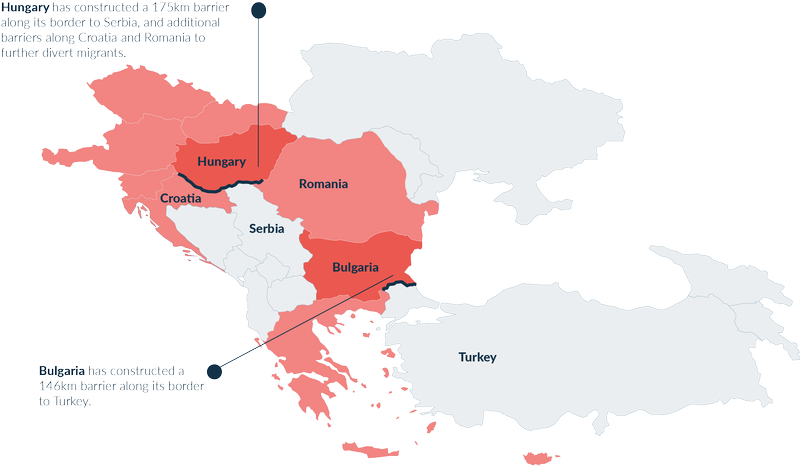

Europe is currently being walled up. One of the most renowned examples is Hungary, where in July 2015, its president announced the construction of a four- meter- high fence along its border to Serbia, to prevent refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan from trespassing across Hungarian national borders. Consistent with that, the Hungarian parliament has approved a controversial law enabling all asylum seekers in the country to be detained in “transit areas” (camps) and forced back to neighboring Serbia. As of June 2016, nearly 146 km of the 166 km planned barrier, had been constructed on the border between Bulgaria and Turkey as a response to increased migrant flows. New border walls and fences often displace migrants between different borders. As a result of the large number of migrants and asylum seekers who have traveled through Greece in the past few years, Greece has increasingly fortified and militarized its border with Turkey – including areas with landmines hidden from earlier conflicts. This process resulted in large numbers of migrants displaced between the Turkish-Greek and the Bulgarian-Turkish borders. Along with the rising of physical border barriers, several European states are increasingly limiting the legal international protection of refugees and the possibility of long term settlement for migrants. The recently approved “security decree” in Italy, for example, further criminalizes migrants and facilitates the deportation of asylum seekers.

In the globalized world, freedom of movement remains an unachievable goal, especially for migrants left with no more than their labor force to sell in the transnational capitalist market. The expansion of securitization politics in Europe, the effects of which undermine the stability of democratic institutions, has resulted in the increased criminalization of migrants and the consequent production of a vulnerable labor force.