Turkish foreign policy: structures and decision-making processes

Turkish foreign policy decision-making: Structures

The Security and Foreign Policy Committee

Senior advisors to the President (appointed and non-appointed)

Turkish foreign policy decision-making: Process

Structural and Conjectural Determinants of Turkish Foreign Policy

Perceptions of constraints and opportunities

How to cite this publication:

Siri Neset, Chr. Michelsen Institute, Mustafa Aydın, Kadir Has University, Hasret Dikici Bilgin, Istanbul Bilgi University, Metin Gürcan, Episteme Turkey, Arne Strand, Chr. Michelsen Institute (2019). Turkish foreign policy: structures and decision-making processes. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2019:3)

On 16 April 2017 Turkish voters went to the polls to deliver their verdict on a set of constitutional amendments that would replace the existing parliamentary system with that of an executive presidency. President Receip Tayyip Erdogan and the ruling AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi - Justice and Development Party) campaigned for the YES-vote and won with a small margin despite an uneven playing field in relation to the opposition (OSCE, 2017[1]).

The referendum took place in a crisis-infused political setting, most importantly a state of emergency imposed following the failed coup d’état in July 2016. President Erdogan wielded his control over the cabinet as de facto head of state and started to rule by decree without much parliamentary oversight. In the post-coup crackdowns on the opposition these decrees led to mass purges in all sectors of Turkish society, restrictions on freedom of speech, movement and assembly. It was in this context the referendum was held. Although the YES side did not manage to mobilize more than 51,4 % of the voters, it was sufficient to set the course for the implementation of a presidential system in Turkey with few institutional checks and balances. Together with the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) Erdogan brought the scheduled parliamentary and presidential elections forward by 17 months, presumably due to the looming economic crisis in Turkey. These elections on June 24, 2018 were to represent the formal shift to the new governing system irrespective of the outcome, as approved in the referendum. Upon winning the presidential election, President Erdogan completed his long-term goal to transform Turkey`s governing system into a presidential one; transitioning from the de facto control he has been exerting since he became president in 2014 to formal powers within this new system.

[1] https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/turkey/303681

Introduction

This CMI report presents the existing foreign policy structures and decision-making processes under the Turkish Presidential system. The data is accumulated through the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs funded project; “Policy Choices in Turkey`s Second Republic Phase” jointly undertaken by researchers from Chr. Michelsen Institute, Kadir Has University, Istanbul Bilgi University, and Episteme Turkey.

Our research has revealed that there is not much known about how foreign policy is decided upon within the Turkish presidential system. A review of the academic literature has identified very few articles in English about this system or related subjects. The focus in the literature is more on the establishment of the system, rather than its processes and functioning (Esen and Gümüşçü 2017; Esen and Gumuscu 2016; Aytaç, Çarkoğlu, and Yıldırım 2017; Taş 2015). A search through the literature prepared by think-thanks and foreign policy institutes generated some papers. In general, these address the expected changes in Turkish foreign policy under the new Presidential system. However, similarly to the other articles, they do not address the structures and processes that the presidency and/or new political elites may apply to foreign policy decision-making (see for example, CSIS, Sinan Ulgen, Carnegie affiliated for Foreign Policy and Brookings[1]). There is one English book (published by the Turkish policy institution SETA, edited by Nebi Miş and Burhanettin Duran[2]) that partly explains the rationale for the change to a Presidential system. However, it provides little or no insight into foreign policy structure and processes to be applied within the new system. In the Turkish literature, we identified one article in a local journal that focuses on the structure of the new system in terms of division of powers between the executive and the legislative bodies (Turan 2018). A SETA report focuses on the authority of the presidential office (Gülener and Miş 2017). Another SETA publication provides justification for the necessity of a Turkish presidential system (Aslan 2015). Newspapers also provide some information about how the system would function.[3]

This report is based on information and data collected through interviews with Turkish academics, researchers from think-thanks, conversations with people from different elite segments within the research team`s combined network, and officials in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), including various elite categories close to President Erdoğan. Moreover, we have searched Presidential Decrees and the harmonization laws[4] for information about the new structures and processes of foreign policy decision-making. Presidential Decree no. 1 outlines the specific organizations under jurisdiction of the Presidency, their respective authority and tasks.[5] Regarding foreign-policy making, the decree presents the policy committees, including a Security and Foreign Policy Committee,[6] but describes the general tasks rather than ascribing authority or jurisdiction. Article 26 states that the Committee has the responsibility of formulating policy proposals regarding Turkey’s international relations in general, devising suggestions to improve Turkey’s regional impact and ability to resolve regional conflicts, report on global developments, and analyze the changing global security environment to formulate pre-emptive measures against potential threats. The same presidential decree also re-establishes the Directorate of Foreign Policy Advisory Board (Article 144) within the Foreign Ministry, which traditionally consisted of recently retired and close-to-retirement diplomats.

Turkish foreign policy decision-making: Structures

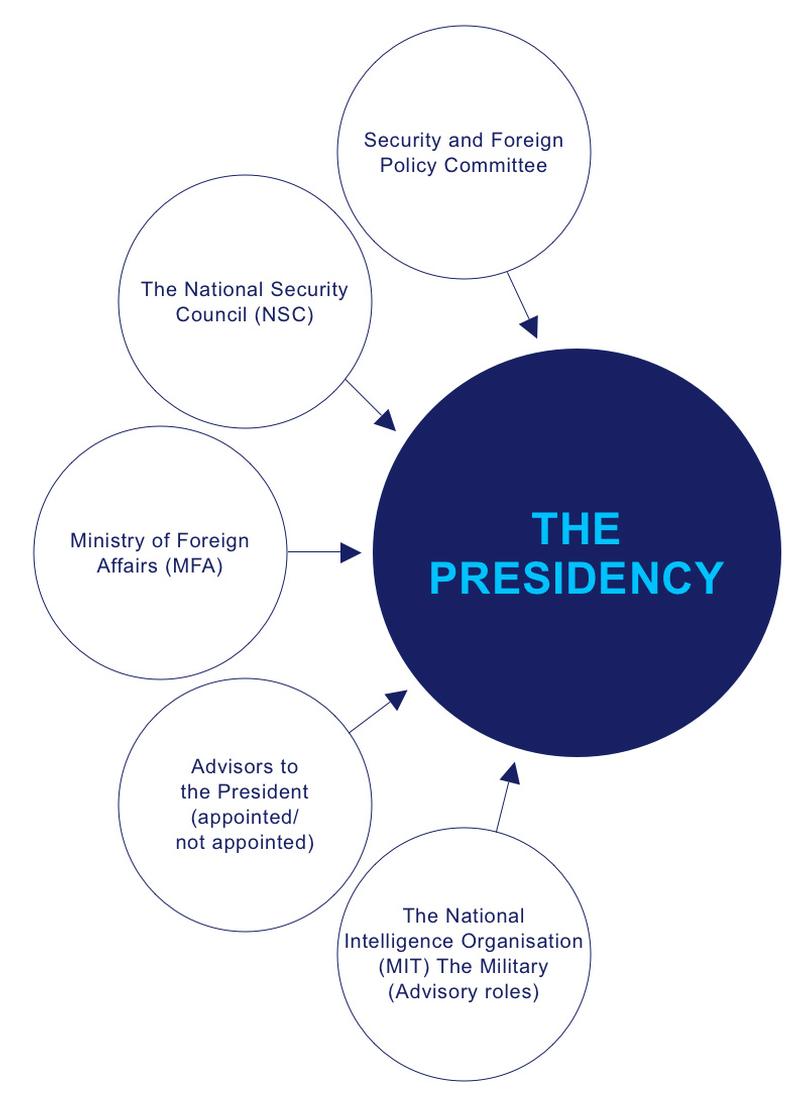

Turkish foreign policy decision-making is divided within and between several entities, and in formal and informal advisory structures. The President is the main authority on foreign policy decision-making. Advisory roles belong to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Security and Foreign Policy Committee, the National Security Council (NSC), the National Intelligence Organization (MIT), formally appointed advisors to the President, and President’s various connections outside the Presidency (the so-called informal advisors), as well as the Turkish Military in an outside influencer role.

Our research indicates that there is no hierarchy organizing these entities and they all provide information directly to the President. The Security and Foreign Policy Committee and informal/formal advisors provide assessments; the MFA, MIT and the military provide practical information. President Erdoğan decides on policy. Through our study, we have learned that the entities named above have no or very limited decision-making power, and the decisions are taken within the Presidency in a highly compartmentalized and personalized fashion. Aside the established units that form a structure of foreign-policy decision making (i.e., the MFA and the NSC, and advisory roles for the MIT and the Military[7]), there is one new entity and two pools of advisors. The Security and Foreign Policy Committee is made of individuals, some of whom were also appointed as senior advisors to the President; thus wearing double hats. Members of the Security and Foreign Policy Committee and the team of advisors within the presidency are publicly known; we have also managed to identify some of the un-appointed advisors from outside the Presidency. We have attempted to map who is working within this advisory structure, the connection between them and their relationship with the President.

The Security and Foreign Policy Committee

From the outset, the Security and Foreign Policy Committee`s mandate was described in the Presidential Degree Number 1 as “responsible for proposing new policies, oversee implementation of policies and take macro decisions”.

Nine members of the council are academics, and there are also professional advisors and journalists with personal relations to the president. As with all the other presidential committees, the President is the official chair of the Security and Foreign Policy Committee. However, in practice, İbrahim Kalın, the Chief Advisor to the President, currently acts as the deputy chair.

What is worth noticing is the apparent lack of appointed members with formal connections to the MIT, the regular military[8] and former or current diplomats who one would assume to provide valuable information/knowledge on foreign policy developments. Also worth noting is that the Committee has no permanent secretary, meaning that there is no regulative mechanism delivering the Committee’s recommendations to the President in an institutional fashion.

We have come to know that the Security and Foreign Policy Committee normally meets every second week, sometimes every week. The appointed members are given work dossiers according to their expertise and are assigned to prepare reports. This work primarily revolves around producing scenarios for future foreign policy developments. However, the members also produce reports on “real time issues”. The members are entitled access to all information from all institutions, such as the MFA and MIT. In practice, however, they have to request information and reports from these institutions through the Presidency and rely on whatever report/information is given to them.

From our interviews and conversations, it emerged that the members of the Security and Foreign Policy Committee are currently preoccupied with pressing foreign policy issues rather than policy planning. If a new Turkish foreign policy doctrine is to be formulated, this group will write it. We assumed that the change in governing system in conjunction with President Erdogan`s much touted “New Turkey” rhetoric would (and indeed should) lead to an overhaul in the overall foreign policy strategy. However, according to our sources, no such new doctrine is in the making or is expected in the foreseeable future.

Senior advisors to the President (appointed and non-appointed)

Within the Presidency, there are several appointed (foreign) policy advisors to the President. According the SETA textbook Turkish bureaucracy became too powerful in policy decision-making and policy development regarding the elected politicians.[9] This needed to be changed through the development and implementation of the Presidential system. According to SETA, the President forms a team of experts-executives at the top levels of the government to ensure that “expertise will be the main factor behind such appointments”.[10] However, in interviews with academics that holds views close to President Erdoğan's, we noted disappointment in Erdoğan's selection of such experts. Several interviewees observed that Erdoğan has so far mainly selected his advisors based on personal trust and loyalty rather than on merit. Their view was that the consolidation of the presidential system would suffer from such a practice. The total number of appointed advisors across all areas is around 40; this is very different to the relatively narrow circle of advisors that President Erdoğan previously relied on. Note however that very few of these advisors have a foreign policy portfolio. The advisors are a mix of people from different backgrounds such as political, academic, journalistic and diplomatic. The closest or most used appointed advisors all have some sort of historical relationship to Erdoğan. The pool of informal advisors (not appointed) that we through our research has identified, is drawn from different networks of friends, business people, academics, experts working in different think tanks and experts on countries of interest to Turkey.

There is one more group of consultants that is worth noticing; the ones that President Erdoğan has a special trust in. Included here are the Minister of Defence Hulusi Akar, Director of MIT Hakan Fidan, Vice-President Fuat Oktay, Minister of Finance and Treasury (as well as Erdoğan’s son-in-law) Berat Albayrak and the Chief of the Cabinet Hasan Doğan. Foreign policy making is a 'reserved domain' that all advisors are not permitted to operate, but some 'selected ones' have say at the presidential palace. Consultancy role of Akar, Fidan, Oktay, and others should not be underestimated. However, Hasan Doğan and Berat Albayrak is said to be the ones currently prioritizing Erdoğan’s agenda and deciding on when/under what conditions Erdoğan is meeting with people.

There have been 21 presidential decrees to this date; however, none of the decrees other than decree number 1 has so far formulated harmonization legislation, which would clarify the making of foreign policy in practice. This is an important issue as it suggests the continued absence of consolidation of presidential system and lack of a consensus as to its practical application.

Turkish foreign policy decision-making: Process

Everyone interviewed, except staff at the Turkish MFA, were of the opinion that foreign policy formulation and decision-making was executed within the Presidency. The MFA interviewers, however, stated firmly that the MFA was the decision-making and policy formulation body within the government. In one interview within the MFA, the interviewee first claimed that the MFA was the decision-maker/policy formulator, but later answered a similar question about decision-making process by saying: “It`s even confusing to me”, and another by stating: “the MFA will get back its power because it will be too difficult to handle all the information within the Presidency”.

We note a state of confusion that may be traced to the fact that historically the Turkish Foreign Ministry, which has been highly regarded institution within and outside Turkey, was solely made up of career diplomats, who charted and guided the implementation of Turkish foreign policy. The Foreign Ministry, together with the Military and the Ministry of Finance, were regarded as the three pillars within the Turkish state that maintained an allegiance to the Turkish nation and the state rather than the ruling party. Some of our interviewees spoke of a breach of intra-ministry trust due to the revelation of Gülenists within the diplomatic corps,[11] and because of the ever-growing number of political appointees (13% at ambassador-level). The lack of trust between MFA colleagues is assumed to lead to poor communication within and between the different departments because individuals hold back information or bypass their closest leaders due to mistrust or perceptions of these holding competence and experience below their own. Interviews moreover indicated political polarization and politicization within the diplomatic ranks.

From our research, we understand that the Military, the MFA, the MIT and the Security and Foreign Policy Committee provide information to the Presidency and that all decisions and policy formulations are made there. Members of the Security and Foreign policy Committee report to Ibrahim Kalın, who filters it and takes their assessments on to President Erdoğan, although without concrete advice on actual policy decisions or evaluations of the implemented policy. Furthermore, the ministries and directorates provide the Presidency with practical information. Hence, it seems like all decisions are taken within the Presidency, where President Erdoğan is aided (or not) by his close circle of advisors.

Some of the arguments set forward in preference of the presidential system was that it would speed up decision-making and make the government system better coordinated, more efficient and democratic (Serdar, 2017).[12] However, our interviewers reported great difficulties in their daily work due to inertia in government and bureaucratic affairs,[13] stemming from uncertainties in the secondary decision-making and/or implementing mechanisms. Bureaucrats, and even some ministers, are reportedly hesitant to take new initiatives and are afraid of making mistakes in the absence of clear political instructions and guidelines. Previously, cabinet ministers had their own areas of responsibility and reported to the Prime Minister or the President, or both. In contrast, the new presidential government system places the responsibility with the Security and Foreign Policy Committee and the Presidential offices. Their responsibilities overlap with the responsibilities of the MFA. The structure of the system continues, so far, to be shaped by Presidential Decrees rather than any kind of harmonization laws. This is a critical issue as it circumvents the Parliament in the transition to the new system. Moreover, the decrees are very general and lack clarification on the division of powers and jurisdiction among the different state institutions. As far as foreign policy is concerned, this enables the Presidency to monopolize decision-making in the absence of a legal framework which would constrain the executive branch. This ambiguity and personalization of decision-making also fed by the hesitation of the bureaucratic institutions to participate in the decision and policymaking process given a widespread confusion regarding areas of jurisdiction.

In theory, the advocates of the presidential system argue that the Parliament would have much to say in foreign policy-making since the foreign policy actions of the President would be audited by the Parliament. However, since President Erdoğan is also the leader of AKP, and since AKP together with its alliance partner MHP holds the majority in the Parliament, in practice, there will not be much scrutiny by the Parliament on foreign policy, at least for now. There is a possibility that we might see a split between MHP and AKP on issues where MHP thinks President Erdoğan is diverting too much from the nationalist agenda/ideology of MHP. Such issues might be Kurdish issue in general and the security strategy concerning the PKK[14] more specifically. Or it might be regarding international alliances with western countries, especially, but not limited to, the US because of MHP’s suspicion of internationalism. It might also be on the case of (a political solution to) the Syria conflict that MHP defines from the outlook of containing Kurdish influence.

In theory, non-governmental actors such as academia, civil society organizations, think-tanks, and media outlets are supposed to have a say in foreign policy in Turkey. How this actually works (or not) needs more exploration. Are critical voices being heard? If so, through which channels? The Turkish media system[15] is referred to as the ‘pool’ system, as the incumbent party gradually eliminated the free press via intimidation and co-optation. The state of emergency, which has been in effect since the putsch attempt on July 15 2016, most significantly affected media and the academy. In these conditions, it is not realistic to expect non-governmental actors to be influential in foreign policy making.

Are opinions on foreign policy formulated on an institutional level or do they stem from selected advisors? Our impression is that selected advisors from the non-government sector contribute to the understanding of different foreign policy areas and that different organizations are not contributing with their institutional knowledge regardless of political leanings.

Structural and Conjectural Determinants of Turkish Foreign Policy

There are (at least) two objectives to the study of foreign policy decision-making. One is to attempt to explain already implemented foreign policy, the other is to try to predict future foreign policy directions. The first step in any of these objectives is to identify the structure and process of foreign policy decision-making within any given country. To determine the leadership`s definition of the situation, it is important to find out who is making the decisions, the pool of people contributing with their expert-knowledge and advice on foreign policy (including their world-view), as well as the nature of the process between the decision-maker and advisors (and institutions) is an important factor so as to determine the leadership`s definition of the situation. That is; how they define/perceive a given foreign policy issue.[16] This project has taken a first step in mapping these structures and processes. A next step in understanding Turkish foreign policy under the new presidential system would be to analyze President Erdoğan’s advisors; their background, world views and stands on international issues so as to understand what kind of information and advice is given to President Erdoğan; meaning; what is the basis on which he is making his decisions?

According to one of our interviewees: “Erdoğan gets information that helps him form policies and make decisions”. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the type of information he is being given by his advisors. It is equally important to take a closer look at President Erdoğan himself. Erdoğan`s sway over the political process in Turkey has recently reached a dramatic level, rarely seen in modern Turkish political history, even considering that the Turkish political culture is traditionally underpinned by dominant leadership. Dominant theories of international relations have traditionally ignored the political impact of different leaders (individual-level variables). In a world where we see leaders like Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, it is hard to argue that personalities and leadership do not affect directions of foreign policy and international relations. As argued by Abelson, “it is a mistake to assume that leaders experiencing the same political event have similar goals and will choose similar responses without suggesting their definitions of the situation and beliefs are somewhat equivalent”.[17] Or similarly as Snyder et al. note: “external reality, or the operational world, is in fact “composed” of what the decision-makers decide is important”.[18]

When a leader, like President Erdoğan, has a leading position in decision-making and has the final word on most policy matters, it is even more imperative to take leadership seriously as well as its agency to manage power relations among different individuals and groups in the state structure and within party cadres. Academia today has the means to study individual personalities and leadership-style through sophisticated quantitative content analysis schemes that have proven to pass methodological reliability and validity tests.[19] Although a personality and leadership style of President Erdoğan is beyond the scope of this project, the research team possess this knowledge and such an analysis will be incorporated in future project proposals. However, some of President Erdoğan`s characteristics, known from previous research, can illuminate the present decision-making process in Ankara. One studyof Erdoğan that applied the Leadership Trait Analysis methodology showed that he is prone to categorical thinking and tends to miss relevant cues for a failing policy action.[20] Further, that he is inclined to discount discrepant feedback from the environment. The study also showed that Erdoğan focuses on the expectations and opinions of his followers at the expense of solving problems. His profile discloses that he is prone to push the limits of what is possible, something seen in Erdoğan`s seemingly subjective perception of his influence on the international arena that often does not correspond with reality. We observe this in the (frequent) cases where he attempts to project power beyond what Turkey is actually capable of achieving. Sometimes he fails because of his tendency to be ‘too direct and open’ in his use of power, unintentionally signaling to his opponents how to react.

Nonetheless, foreign policies are not made in a vacuum. Foreign policy making bodies of any state receive inputs (demands for action, values, threats, feedback) from the outside world and respond to these inputs.[21] The problem of how to analyze inputs and corresponding output is due to the elastic character of these factors and therefore there is a need to extract the factors that contribute to the foreign policy decision-making of the country of interest. Experience and tradition over time, in combination with basic values and norms, create a set of relative inflexible principles. Aydin[22] argues that the interplay of two kinds of variables shape Turkish foreign policy: structural variables and conjunctural variables. Structural variables are continuous and relatively static and can exert long-term influence over the determination of foreign policy goals. Structural variables include geographic position, historical experiences and cultural background, together with national stereotypes, images of other nations and continuing economic provisions. Conjunctural variables are made up of a web of interrelated developments in domestic politics and international relations. They are dynamic and subject to change under the influence of domestic and foreign developments and exert influence on short-term foreign policy implementation. Structural variables include shifts in international power-balance, domestic political changes, and personalities of specific decision-makers.

In this project, we have started to explore structural and conjectural determinants of Turkish foreign policy. We have focused on perceptions of structural determinants and worked on finding out the conjectural variables that are currently shaping foreign policy decisions.

Structural variables

We initially focused on the structural variables identified by Aydin above. However, early in the project we found that focusing on all of these would be too comprehensive due to time and resource restrictions. Thus, we ended up focusing on the perception of constraints and opportunities due to geographical position and national image.

Perceptions of constraints and opportunities

Many of our interviewees declared that Turkey was surrounded by instability and conflict and that these pose a threat to the country and restrain the possibility of long-term planning, for example, developing a strategy or foreign policy doctrine. However, within the MFA they denounced the idea that a doctrine/strategy was lacking, referring to the currently employed “Enterprising and Humanitarian Foreign Policy” concept. Through analysis of written sources and from interviews and conversations, we are under the impression that the government wants to project the idea of “Big Turkey” regionally and globally through “morale” and “effectiveness”. However, there are no traces of a definitive strategy to this end. Military and foreign policy do not seem founded in a grand strategy and are rather made up through tactical moves. Some of those we spoke echoed the Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavuşoğlu in describing the neighborhood as weak, poor and fragile.[23] Our interviewees spoke of a changed perception of security because of the Syrian conflict, especially because of the multifaceted enemy image and because of multiple actors involved. The different actors placed different constraints on Turkish foreign policy and the Russian and American presence in the region especially hindered the projection of Turkish military power. The Black Sea region was also put forward as an example of Russian presence. One interviewee who holds views close to Erdoğan said: “Before the annexation of Crimea, Turkey was able to balance Russia in the Black Sea region, but not now”. These interviewees reported that Turkish military power is diminishing, but also that the use of hard power is a rising trend and, though risky, it is likely to continue. When we talked to interviewees about constraints and possibilities, there was usually much talk about constraints and little about possibilities. This may reflect the feeling of being “challenged in a ring of fire” as described by the Foreign Minister,[24] but may also reflect the interview guide. To fully understand the perception of opportunities, more interviews should be carried out.

National image

In simple theoretical terms, national image is the combined perception of one`s own country and the perception of how others view the country. Most of our interviewees close to President Erdoğan spoke of resilience, strength and pride. And Turkey wants to make a difference in the world and conducts itself based on these principles. They also spoke of greatness ahead due to the Presidential system. They spoke proudly about Turkey`s accomplishments around the world: humanitarianism and membership or leadership of important international institutions and military operations. In earlier studies,[25] we found the same “self-image” across different elite categories. However, currently two issues are reported that differ greatly from the perceptions of the other group. One is Turkey’s resilience, where our contacts speak of the polarization within the country as seriously endangering the internal stability. The other relates to the economy when they report the downgrading of the Turkish economy as something that will weaken Turkey internationally on a humanitarian, military and international partner level. None of the interviewees with views close to President Erdoğan mentioned either polarization or the economy. When asked directly about the economy, they either said that this was a temporal problem due to the “war on Turkey” led by some international actors or flatly denied that there were any problems in the Turkish economy. Asked directly on polarization, some said that the “other side” would “come to their senses” or that it was no problem.

How our contacts believe other countries view Turkey became more difficult to assess. This is because in our interviews, when we tried to ask about this, the respondents shifted to a related (but theoretically not the same) issue, namely, ‘how they view other nations; generally friendly or hostile to Turkey’. With varying degrees of emotionality, many of our interviewees portrayed the West as hostile towards Turkey; in the EU that counted for both population and leadership, in the US it was more the US institutions that were mentioned (State Department, CIA, Justice Ministry). NATO as an institution was not put in this category and a surprisingly high number of interviewees portrayed Jens Stoltenberg almost in positive terms (however, this might be because the interviewer was Norwegian!). Within Europe and the Nordic countries, the leadership (also the Norwegian MFA/government) was framed as being too friendly to pro-PKK European groups and as such were undermining Turkey`s interests and security. “Brussels” – the EU parliament was, by some, described as hijacked by PKK (at best) or in alliance with PKK (at worst). Russia was portrayed as the country that supported and helped Turkey at one of its worst moments (during the coup attempt), but at the same time as a country that was both a strategic partner and one that had interests conflicting with those of Turkey.

Conjectural variables

Through discussions within the team, with our wider network and through interviews as well as reading of articles, reports and news articles, we have formed an opinion on Conjectural Determinants of Turkish Foreign Policy. However, more research is needed to be able to (in line with academic standards) confidently confirm these conjectural variables, which are;

- Government system;

- Economic constraints;

- Geopolitical situation balancing between Russia, the US, and the EU;

- Regional re-alignments;

- Kurdish Issue.

We are of the opinion that these variables could be considered drivers in foreign policy formulation and/or decision-making and as such well worth having in mind as one follows Turkish foreign policy. For the sake of simplicity, we have combined these variables into three factors/sections.

1. The nature of political regime

Domestic political and decision-making structures have an important role to play in the formulation of foreign policy. For example, in democracies, the very nature of democratic multiplicity of interests rarely permits unanimous approval of a policy. Thus, democratic governments must rule by compromise and make internal concessions to gain endorsement for foreign policies or vice-versa.

The mechanisms of decision making also differs according to the political system of a country. For example, in democracies, parliamentary supervision remains active and even in wartime the leader of a parliamentary democracy must account to the legislative body. On the other extreme, dictatorships for example permit decision-making without the supervision of parliamentary bodies. In a dictatorship, a foreign policy decision is made secretly, without controls and restraints, which means that the decisions and subsequent actions often happen quickly.

Similarly, the masses may be swayed by irrational ideologies and charismatic leaders. Therefore, institutional behavior is also relevant. The institutional structure of a country determines the amount of the total social effort, which can be devoted to foreign policy. Aside from the allocation of resources, the domestic structure affects the way the actions of other states are interpreted. In the contemporary period, daily issues are usually too complex and relevant facts too manifold to be dealt with based on personal intuition. Therefore, bureaucratic mechanisms emerge within states to aid the leaders to choose between options. However, over time, they can develop a momentum and a vested interest of their own, and certain governmental influences may be brought to bear upon the administrators of foreign affairs.

Another effect of institutional structures could be seen in the concentration of authority: in the difference between centralized and decentralized government structures. The greater the concentration of authority in a single individual or small group, the greater the likelihood that subordinate policy-makers will withhold criticism and seek to provide the information and recommendation that they perceive their superiors to want.

As a result, the system with which the country is governed has significant impacts on its foreign policy. In this context, Turkey has passed through several governing systems during its existence as an independent state, most recently with a move from a parliamentary system to presidential system. The effects of this change on foreign policy must be examined in detail.

2. Economic Dynamics

The socio-economic conditions of a country, which are closely connected with its political evolvement, form an important factor of foreign policy. The standard of living, the distribution of income, and the social structure related to the facts of production and consumption are elements of social strength or weakness. While political institutions, civil rights, political stability are measure of political vigor. Social strength and political stability are closely interwoven. The degree to which the economy of a state has developed may have important consequences for its foreign policy as different states at different levels of developments have different needs and therefore different links to their environments. Moreover, the level of economic development contributes to the internal demands from governments to formulate external policies that reflect and serve the diversity of interests that it produces.

The level of economic development may also be effective in determining a state's capability to implement its foreign policy plans. The more a country is developed, the larger is the proportion of its GDP that is likely to be devoted to external purposes, whether these be military ventures, economic aid programs, or extensive diplomatic commitments.

3. Regional and global political developments

Although states try to plan and have long-term interests in their international relations, almost 95 percent of the daily foreign policy actions are reactionary and responding to national, regional and global changes. In this context, there are many areas that remain to be studied in relation to their effects on Turkey’s choices in international connections and foreign policy:

- Domestic political developments in Turkey during the period under consideration (such as dealing with changing aspects of Kurdish issue, military’s influence on political scene, rise and decline of FETÖ, etc.),

- Regional geopolitical realignments (such as the resurgence of Russia as a power broker in Turkey’s neighborhood from the Caucasus to Syria; intensification of regional power rivalries between Saudi Arabia and Iran, between Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt; emerging rivalry in the eastern Mediterranean between Turkey and the rest of the countries in the region, etc.)

- The changing global geopolitical scene (such as increased competition between Russia and the US, not only in the Middle East but also in the Black Sea and the Eastern Europe; disconnection among the NATO allies; various domestic weakness and problems of the EU; large scale movement of refugees across borders; rise of populist approaches in global politics, etc.).

Conclusion

This report has described how the Turkish state functions when it comes to foreign policy decision-making under the new presidential system. There have been 21 presidential decrees to this date; however, none of these, except Presidential Decree Number 1, formulates harmonization legislation to synchronize Turkey`s laws with the amendments passed in the referendum. Thus, there is virtually no unified legislation to clarify the making of foreign policy in practice. This is an important issue as it suggests the continued absence of consolidation of the presidential system and lack of a consensus between the different entities (ministries etc.) involved as to its practical application.

Our findings show that the main decision-making body is the Presidency whereas different entities have advisory roles, including networks of informal advisors. The processes of decision-making involve parallel sources of information provided to the Presidency that makes up the basis on which the President and his closest aids make decisions on foreign policy.

More research is needed on the leadership style of President Erdoğan as well as his agency to manage power relations among different individuals and groups in the state structure and among AKP cadres. A next step in understanding Turkish foreign policy under the new presidential system would also be to analyze President Erdoğan’s advisors: their background, world views and stands on foreign policy so as to understand what kind of information and advice is given to him.

In addition there is a need to understand the factors that contribute to the foreign policy decision-making of Turkey under the new system. Since the end of the Davutoğlu era, there has been a vacuum when it comes to formal doctrine of Turkish foreign policy and thus there is little known about what structural and conjectural determinants that shape policies. In this project we have started to map these factors. When it comes to structural variables we started looking into perception of constraints and opportunities in connection with geographical position and national image. Furthermore, through our research, we have identified several conjectural determinants of Turkish foreign policy: the government system; economic constraints; the geopolitical situation; regional re-alignments; and the Kurdish issue. Clearly, more research is needed to be able to confidently confirm these conjectural variables.

Notes

[1] CSIS: https://www.csis.org/analysis/erdogan-takes-total-control-new-turkey

Foreign Policy: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/02/turkeys-foreign-policy-is-about-to-take-a-turn-to-the-right/

Brookings: https://www.brookings.edu/research/turkeys-new-presidential-system-and-a-changing-west/

[2] https://www.setav.org/en/turkeys-presidential-system-model-and-practices/

[3] Please see (Sabah n.d.; Bianet - Bagimsiz Iletisim Agi n.d.; yeniakit n.d.)

[4] Harmonization laws are laws designed to synchronize Turkey’s laws with the far-reaching amendments passed in the referendum

[5] The presidential decrees are accessible online at the Legislation Information System (http://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/CKHK.aspx).

[6] Presidential Decree No.1; official gazette publication date-number, July 10, 2018-30474.

[7] The military has an advisory role as part of the NSC. MIT in its own capacity.

[8] But there could be ties through three of the members that through their former employments and/or affiliations have connections to the Military and/or the MIT.

[9] https://www.setav.org/en/turkeys-presidential-system-model-and-practices/

[10] https://www.setav.org/en/turkeys-presidential-system-model-and-practices/ Page 245

[11] The Gülenist are the followers of the former Turkish preacher, Fethullah Gülen, who has been living in the US since 1999, and was accused by the Turkish government of masterminding the attempted coup of July 2016. His followers since then are identified in Turkey as the ‘Fethullah Gülen Terror Organization’, or FETÖ in short.

[12] https://www.dailysabah.com/op-ed/2017/04/15/turkish-foreign-policy-under-the-new-presidential-system

[13] This may not be directly linked to foreign policy but there is no reason to think that this problem isn’t present also within the MFA and other ministries linked to foreign policy.

[14] The PKK (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê – Workers’ Party of Kurdistan) has been waging terror attacks on Turkey since 1984 and is classified as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the USA, and the EU.

[15] Apart from the state-owned TRT, most of the media (both print and TV) are owned now by Erdoğan sympathizers and/or collaborators. Fox TV (due to its international ownership), HaberTurk are moderate-centrist and relatively bipartisan nation-wide TVs, Halk TV is an opposition TV. A few smaller cable TV stations with critical positions on the government also exist, but they are not widespread or influential. Sözcü and Cumhuriyet are the only mass newspapers that oppose the government, all the others are now owned by pro-government businessmen.

[16] Snyder, R. C., Bruck, H. W. & Sapin, B. (1962). Foreign Policy Decision-Making: An Approach to the Study of International Politics. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe.

[17] Abelson, R. (1986). Beliefs are like Possessions. Journal for the theory of Social Behavior, 16, 225.

[18] Cited in Hudson, V. M. (2005). Foreign Policy Analysis: Actor-Specific Theory and the Ground of International Relations. Foreign Policy Analysis, 1, 3.

[19] See for example; Young, M. D. (2000). Automating Assessment At- a -Distance. The Political Psychologist, 5, 17-23.

[20] Görener, A. Ş., & Ucal, M. Ş. (2011). The Personality and Leadership Style of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan: Implications for Turkish Foreign Policy. Turkish Studies, 12, 357-381.

[21] Aydin, M. (2004). Turkish Foreign Policy Framework and Analysis.

[22] ibid, p.5

[23] Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavuşoğlu speech at the 10th ambassador’s conference, Ankara, August 2018.

[24] Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavuşoğlu speech at the 10th ambassador’s conference, Ankara, August 2018.

[25] Neset and Heradstveit, 2013 (project funded by the MFA 2012-2014, MEU 12/0056)