Community-Driven Development or community-based development?

Community-driven development in fragile contexts

A dramatically changed Afghanistan

Community-driven development in Afghanistan

Organisation and project overview

Earlier evaluations and documented impact

Sustainability of interventions

Inclusion of women and marginalised groups in decision making

Learning points and suggestion for adjustments

Review of Norwegian support for Community-Driven Development in Afghanistan

ANNEX II: Evaluations, baseline assessment and external reports

Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED)

Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR)

Norwegian Afghanistan Committee (NAC)

Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC)

ANNEX III: Interview questions

How to cite this publication:

Arne Strand, Magnus Hatlebakk, Torunn Wimpelmann, Mirwais Wardak (2022). Community-Driven Development or community-based development? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2022:3)

Review of Norwegian-funded CDC projects in Afghanistan

Abbreviations

ACTED – Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development

ADA – Afghan Development Agency

ALP – Accelerated Learning Program

ARTF – Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund

AWEC – Afghanistan Women’s Educational Center

AWSDC – Afghanistan Women’s Skills Development Centre

CAWC – Central Afghanistan Welfare Committee

CBE – Community-Based Education

CC – Citizens Charter Programme

CDC – Community Development Committee

CoAR – Citizen Organization for Advocacy and Resilience

CMI – Chr. Michelsen Institute

DACAAR – Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees

DDA – District Development Assemblies

DRR – Disaster Risk Reduction

ICLA – Information, Counselling and Legal Assistance

MFA – Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MRRD – Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development

NAC – Norwegian Afghanistan Committee

NCA – Norwegian Church Aid

NGO – Non-governmental Organisation

NRC – Norwegian Refugees Council

NORAD – Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation

NSP – National Solidarity Project

PTRO – Peace Training and Research Organisation

RRAA – Rural Rehabilitation Association for Afghanistan

SCCP – Social Council for Consolidation of Peace

SDO – Sanayee Development Organisation

WASH – Water, sanitation and hygiene

Executive Summary

This review of Norwegian support for Community-Driven Development projects in Afghanistan was initiated by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) to cover their support to five non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with an emphasis on the period 2018 -2021. These were the Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED), the Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR), the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee (NAC), Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC).

Initially, Norwegian support prioritised the Faryab province in north-west Afghanistan, but the NGOs implement Norwegian-funded rural development projects in several other provinces. This review, undertaken by CMI in collaboration with the Peace Training and Research Organisation (PTRO), combines a desk review of NGO-provided documentation with interviews with NGO headquarters in Kabul and fieldwork in Faryab, Badakhshan and Ghazni provinces during December 2021 and January 2022.

We first present the literature on community-driven development in fragile contexts, where the main success criterion identified that sets such projects apart from other development projects is the degree of involvement of the local population. However, the literature warns us to expect challenges imposed by insecurity, competition over resources and the potential for aid capture. In the literature review, we draw on some empirical evidence from the National Solidarity Programme (NSP) and the establishment of the Community Development Councils (CDC).

To contextualise this review and our findings do we identify the dramatic changes Afghanistan has gone through over recent years that have led to increasing insecurity and uncertainty, culminating with the collapse of the Afghan government under President Ghani on August 15, 2021. We reflect on how these changes affected NGOs’ ability to operate, collaborate with Afghan communities and continue support for women, girls, and marginalised groups. The NGOs included in this study experiences limited changes to their local operations and programmes, though uncertainty over future restrictions on their operations were noted.

A main initial challenge posed by the international sanctions was to get funding into Afghanistan and access accounts in Afghan banks, this proved especially challenging for Afghan NGOs. This had gradually been overcome using traditional transfer mechanisms and later utilizing a United Nations system. It is difficult to compare NGO’s experiences with Taliban rule during this 6 month + period with their time in power during the 1990s. Their emphasis remains on law and order, but Afghans have very different expectations from a government this time. One important similarity noted during fieldwork is how local community manged to influence on Taliban’s local practise to meet community expectations and demands. Girls access to higher education and the women’s access to jobs and projects are examples of successful local pressure, though not always broadly publicised.

We discuss the notion of Afghan community-driven development in some detail before we present an overview of the Norwegian-funded activities of the five NGOs and compare their approaches with the types of community organisations they interact and collaborate with. This varies largely from ACTED’s manteqa (district) approach, NAC’s expanded CDC approach, NCA’s and their partners’ priority for CDC involvement and DACAAR’s and NRC’s linkage to the CDC structures, while primarily working with project-related committees. A general concern noted in all projects visited was the notion of CDC’s being captured and used by communal elites and strongmen for their own purposes, where the extent of corruption and nepotism disqualified them in the view of many communities as being their legitimate representatives. However, it was demonstrated that a thorough NGO involvement with CDC structures and enduring their involvement was an anti-dote to project and funding capture and misuse.

We then examine the NGO-provided project proposals and reports, base-, mid- and end-line studies, monitoring reports and internally and externally commissioned evaluations to establish to what degree different projects met DAC evaluation standards, what observations and recommendations had been made and whether projects were adapted and changed over the implementation period.

The findings confirm those of a 2020 meta study of development assistance to Afghanistan concluding that due to needs across all sectors, all assistance was found to be relevant; security challenges increased implementation costs; and low capacity within the Afghan government had negative effects on project outcomes, results and impact. Monitoring and evaluation practices were found to be weak and project sustainability challenging to measure. What was determined to be effective were interventions in the education and health sector and small-scale participatory infrastructure projects in rural areas (including those under NSP).

The review discusses in more detail the sustainability of the different NGO approaches and projects, making a distinction between those aimed at training and support for individuals, which the individuals themselves are to sustain, those communities and their organisations are expected to maintain and hold responsibility for, and those ideally taken over by the Afghan government. The very encouraging finding was that recipients and other members of the target communities replicated many individual projects, confirming their value and ability to increase participant’s income. For some of the larger projects (such as water-supply projects), it was necessary to have trained technicians and fee collection for continued maintenance to ensure sustainability, although there were several examples of community reluctance to contribute or expecting NGOs to continue their support. There were few examples of the Afghan government having taken on responsibility for projects, and even less is expected from the current Taliban administration. A general finding – in line with the literature – is that the more the communities are involved in project identification, contribution and monitoring, the greater the likelihood for investments to be continued and sustained, even in the presence of increasing economic and societal vulnerability.

Inclusion of and responses to the needs and rights of women, girls and marginalised groups was of high importance for MFA/NORAD and the five NGOs we surveyed. However, the strong influence of tradition and religious practices in many parts of Afghanistan – and especially in Taliban-influenced and later Taliban-controlled areas – made the pursuit of these goals more challenging. The NGOs applied different strategies toward these goals and had different degrees of including women in community councils, sub-committees or in separate councils, project committees and other types of associations. Their project types varied greatly, from stand-alone projects to those aimed at benefitting both genders. NGOs with a more consistent approach to involving women and to ensuring their influence on priorities and programming had been able to maintain their involvement since the Taliban takeover. Others met with local (and possibly Taliban) opposition and closed some of their projects, while the fieldwork found that most of the NGOs continued their projects for women and girls under the new Taliban administration. We found passing references to inclusion of and assistance targeting marginalised groups (beyond the poor), such as the disabled, but no systematic mention or assessment of such activities.

The general conclusion is that NGOs covered by this review contributed to a number of significant and positive changes in communities and for individuals in Faryab and the other provinces/districts they engaged in. Interviewees and the previous evaluations and reviews found the large majority of the projects relevant, effective and efficiently delivered and to some extent having reduced poverty and vulnerability.

The NGOs and the projects demonstrate a degree of learning adjustments and adaption to changing political, military and societal realities, with most activities ongoing by the end of 2021. Some of the NGOs could have done more to ensure independent field monitoring and evaluations and data collection to enable better impact assessments of impact. This leads us to:

Recommend that MFA and NORA make it obligatory for NGOs have a monitoring system in place and to commission external and independent mid-term and end line evaluations and strengthen their own data collection when supporting projects in fragile contexts. The number and type of external reviews should, however, depend on the scale, type and length of each project.

NGOs related to and engaged with different types of community organisations, though the practice and degree of inclusion of women and marginalised groups varied largely, and thus so did their de-facto ability to influence decision making and prioritisations. NGOs provided limited information to the communities about their project budgets, partly due to concerns for undue taxation or pressure from criminal groups, which reduced the community’s ability to monitor and control assistance allocated.

Of the NGOs we reviewed, we found that NAC practises the closest to the notion of community-led development, and ACTED combines community-led development with assistance implemented in collaboration with community bodies. Meanwhile, DACAAR and NRC, despite their different mandates, are primarily implementing their projects in collaboration with selected community bodies. NCA has a clear intention to promote and support community-led development through Afghan NGOs, which some evaluations confirm to be successful. The selected case poses a question to what extent all their Partners were able to fulfil this intention. This leads us to:

Recommend NGOs to seek knowledge from the NAC model and consider adjusting their own approaches for community engagement. This seems particularly important for the inclusion and involvement of women and marginalised groups, despite the additional challenges and limitations the Taliban administration presently imposes.

Corruption emerged as a recurring theme during the fieldwork, as it was found to direct assistance away from those most in need, to reduce the communal value and impact of interventions and to reduce communal coherence and trust, including in the NGOs and in successive government administrations. This leads us to:

Recommend NGOs to combine internal anti-corruption policies and routines with monitoring, ensuring community (and not only elite) involvement in the project cycle (or aid distribution) and guaranteeing clarity on plans and budgets.

The main conclusion is that Norwegian-funded CDD and related projects have met critical needs in Afghanistan under the period reviewed. Both the NGOs and most of their projects receive a positive assessment in evaluations from the intended beneficiaries and from past and present representatives of the Afghan administration.

While the NGOs continue to provide humanitarian assistance, and the communities welcome this, it is the NGOs’ opinion that this assistance is not sufficient to counter a sharp increase in poverty and that the underlying causes will remain unaddressed if community development projects are discontinued. It is therefore a good thing that while Norwegian funding through the Taliban administration was frozen from August 2021, development assistance though NGOs (including the five reviewed) and multilateral organisations was continued.

This review therefore:

Recommends a continuation of the Norwegian support for community-driven development in Afghanistan, as it contributes to reducing poverty, meeting critical needs of vulnerable populations and ensuring continued support for employment, education and increased societal influence and participation for girls and women.

However, it is important that the support become community-driven, so as to protect it from misuse and diversion towards power elites, now including the Taliban. This might require a degree of contact and dialogue with the Taliban administration locally, as well as transparency about assistance provided and requirements set for community involvement and beneficiary selection.

The broader reflection from the Afghanistan case is that community-driven development has proven to function well in fragile states and context, when sticking to the principle of involving the local population in a meaningful way and finding ways to counterbalance the influence of powerful individuals and groups aiming to monopolise the assistance.

Introduction

This review of Norwegian support for Community-Driven Development projects in Afghanistan was initiated by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), to cover their support of five non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with an emphasis on the period 2018–2021.

Norway has since the early 1980s contributed with emergency relief and later rehabilitation and development assistance in Afghanistan. Since 2001 more of the assistance has been channelled through multi-donor trust funds, contributing towards the Afghan government’s development priorities, combined with support for NGOs included in this study: the Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED), the Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR), the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee (NAC), Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). Norwegian financing of development projects controlled and manged by the Taliban administration were stopped from August 2021, and assistance has since been channelled through UN agencies, development banks and NGOs, including NGOs other than those covered by this review.

Deployment of Norwegian armed forces as a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) to the Faryab province in 2005 led to an increase in allocation of development and humanitarian resources to the province. In addition to Norwegian NGOs, assistance was provided through the Danish NGO DACAAR and the French NGO ACTED, both engaging in different types of rural and community-driven development (CDD). Since the military withdrawal from Faryab in 2014, Taliban intrusion and increased insecurity has imposed a range of challenges for the provincial government and NGOs working in different districts. The projects continued in Faryab and other provinces of Afghanistan, and also included assistance for the internally displaced, provision of legal assistance, accelerated learning projects for children, and conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

With the collapse of the Afghan Government in August 2021 and the uncertainty this brought about, we agreed with MFA/NORAD that this review should not only be backward-looking, but also include an assessment of the conditions for community-driven development under the new Taliban administration. Included in this assessment are the various NGOs’ abilities to collaborate with community organisations and to provide assistance irrespective of beneficiary’s gender, ethnic or religious backgrounds. The aim was to provide a research-based reflection on possible future opportunities for community-driven development in Afghanistan – and the potential role of the NGOs.

The improved security situation allowed for fieldwork in late 2021/early 2022. Researchers from the Peace Training and Research Organisation (PTRO) conducted interviews with NGOs in Kabul, with NGO representatives, female and male beneficiaries and a range of stakeholders in 3 provinces, and then followed up with some clarifying questions for the NGOs.

In the Faryab province, the field team visited 6 districts where ACTED, DACAAR and NRC had their projects. In the Baharak District of the Badakhshan province, the field team visited NCA Partner organisation Afghanistan Women’s Educational Center (AWEC) projects, and in the Jaghori district of the Ghazni province, they visited NAC’s project. This provided this review a degree of diversity in living conditions and representation of different ethnic and religious groups.

Review methodology

The review was trust-based in the sense that the team relied on documentation provided by the five NGOs: their project documents, contracts, various reports and project evaluations and reviews (see Annex II). These documents, and previous evaluation findings and recommendations, formed the basis for the retrospective desk review and were contrasted with a stock taking and situation-based analysis of the project areas following the Taliban’s gaining control over Afghanistan in August 2021. A major emphasis in this report is placed on the findings and observations from the field and project visits undertaken in the three selected provinces, on NGOs updates from March 2022, and on the views and opinions stated by project beneficiaries, different community organisations, community members and government/administrative representatives.

The review as agreed in the TOR (Annex I), placing an emphasis on the period 2018–2021, set out to:

- Compare approaches taken by the different NGOs in relation to how projects are organised in the different locations, how they – in particular cases – have been adjusted and developed over the implementation period.

- Compare and analyse the methods used in earlier evaluations to estimate the impact of the different types of interventions and how important the projects are for poverty reduction, community development and fostering broad participation.

- Compare and analyse the sustainability of the different interventions and approaches for community involvement.

- Compare and analyse the extent of the inclusion of women and marginalised groups in decision making, project implementation and monitoring/evaluation.

- Provide learning points on how projects – if required – can be adjusted and developed to increase participation, impact and sustainability.

It was moreover agreed during autumn 2021 to include the following questions:

- In light of recent developments identify and discuss viability of and limitations to possible options for continuation, implementation and sustainability of community driven development programmes in Afghanistan. This includes questions as:

- What are the NGOs experiences from operating in Taliban governed areas/Afghanistan, including differences and similarities with the first period of Taliban rule?

- What have been the main challenges encountered and (possibly) opportunities arising at national, province and district levels?

- Have they experienced or managed to overcome limitations on movement, employments, implementation of projects or interaction with communities and community bodies, and in particular projects favoring girls/women/minorities?

- Have they experienced pressure to discriminate against girls/women/minorities when providing universal services?

- To what extent has international sanctions, funding restrictions or Taliban policy influenced project implementations, and do they envisage ways to overcome these – individually, collectively – and in case through which mechanisms?

- For the longer run: what implication might these recent changes hold for the importance of and ability to working with and through community bodies and for community driven development projects?

- And, time and budget permitting, provide a comparison of use of international funding mechanisms and implications of sanctions on humanitarian/development funding and implementation from other countries and/ or regions.

The filed visits took place during December 2021 and January 2022 after review of the provided documentation and initial semi-structured interviews with the five NGOs in Kabul. Based on these initial findings was a fieldwork guide developed for whom to interview and whom to seek information from (key informants) or run focus group interviews with to ensure uniformity in data collection between the NGOs, projects and locations (see Annex II). Given Taliban’s restrictions on women’s mobility and interactions with non-family males, we considered it unfeasible to send female researchers into the field. The fieldwork was consequently undertaken only by male researchers. Efforts were therefore made in all three provinces to ensure inclusion of women among interviewees and with a strong representation in the focus groups discussions. Of the total interviews, 66 were with men and 38 with women, and most of the women took part in focus group interviews, with targeted gender questions, or were interviewed during project visits. Nonetheless, a more gender-balanced team would have enabled consultation with more women and thereby would have been able to provide a deeper understanding of their degree of influence and assessments of the different programmes. To counter this potential bias emphasis was placed on the gender and minority aspect when reviewing the NGOs own reporting, and their monitoring and evaluation reports.

Testing of validity of data and results, which some of the NGOs’ evaluations suggested should be improved, was also an aim for the fieldwork when emphasising the experiences and opinions of the project beneficiaries. The limited selection of projects and number of interviews, especially including women, limited our ability to test the reported data in a systematic manner.

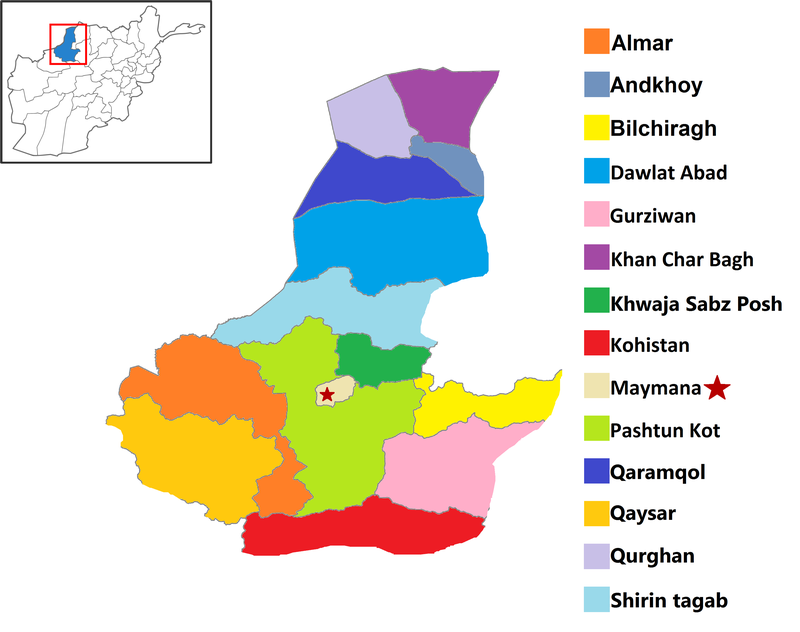

In Faryab two researchers (including the team leader) visited six districts, including Maimane, Qaisar, Almar, Khwaja Sabz Push, Sherin Tagab and Dawlatabad. There were interviews with NGO staff at the province level and with six government officials at the province and district levels. The team was accompanied by the NGOs to the districts, but set up their own interviews with NGO staff and community members. There was a total of 68 interviews, some of which were more informal discussions with project participants and assistance recipients during project visits or at vocational training centres or education classes.

In Badakhshan two researchers visited the Baharak district, and the three villages AWEC worked in. Interviews were made with the Head of Economy department, a villages officer (Modir Qariajat) in the Baharak district, the AWEC project officer, four female (interviewed by phone) and three male members of the AWEC Shura, four CDC members, and four community male elders who were neither part of the CDC nor of the AWEC Shura.

In the Jaghori district, one male researcher visited the centre, Sangemasha, and Chelbaghto and Patoo villages. Researchers interviewed three government officers, four NAC staff members, five other individuals, including one female in Chelbaghto; four community elders, including one woman in Patoo; and five individuals, including shopkeepers, taxi drivers and elders, in Sangemasha.

The interviews were complemented by requests for further written details from some NGOs and verification of information obtained and comments on and supplements to the team’s field observations. This allowed for an update in early 2002 on NGOs ability to operate and if they experienced limitation on employment or movement of female staff or women’s project involvement and participation.

Community-driven development in fragile contexts

Community-driven development (CDD) is not a well-defined concept, and tends, strangely, to describe development projects that are externally funded and monitored against goals that external agencies set. The community element includes attempts at involving the local population in identifying target groups, sub-goals, prioritising between sub-projects and various ways of spending funds, and/or involvement in implementing the projects in terms of labor, co-financing, or management. The funding agency will normally have goals that can reasonably be linked to community development, such as local governance, democracy and an active civil society, and quite often the projects focus on sectors that are likely to have direct local impacts such as education, primary health, microfinance, agriculture, microbusiness, and local infrastructure. The CDD term thus covers a wide range of development projects. One may argue that the main success criterion, which will separate it from any other development project, should be the degree of involvement of the local population. Meanwhile, it would seem that general impact evaluations that focus on other goals, such as poverty reduction, income generation, etc., should be secondary, unless community involvement is considered to be a means to reach these other goals, rather than being a goal in itself.

Below we will review both issues, that is, CDD as focused on community involvement, and as a means to reach other targets. In both cases we will focus on externally funded projects, and thus not review variations on, nor preconditions for, the potentially more effective community-driven development that happens independently of national governments or aid agencies. This narrow focus is motivated by a need to judge the efficiency of aid funding. We will still bring independent community development into the picture, as this will be an alternative to any externally funded development project, and thus will constitute the control the community exerts without external aid. One may well imagine that external projects may even have a negative impact on local development, especially if they crowd out local initiatives. The review will start with a general discussion, and then will shift to a review of empirical contributions, with a particular focus on fragile contexts.

CDD as community involvement

A core aim of CDD projects is to involve the local community in the development process. Ideally, this includes involvement at all stages of the project, from setting the goals, via identifying target groups, prioritising sub-projects and budgets, to monitoring implementation and evaluation of the results. But since CDD projects of the type we discuss here come with external funding, there will immediately be competition for those funds, and local strongmen will naturally be better positioned to take their share. Such local capture may even be appreciated by the local population as they in fact understand the political economy of aid, and thus that the externally funded projects may not have appeared in the first place without the efforts of the same village leaders. What will then be the best strategy for an aid agency that also understands the political economy of aid? That is, how can one ensure real local involvement beyond local leaders? This is covered by the literature, normally using principal-agent theory, which is a sub-field of game theory where the principal (the aid agency, or even the local elite) moves first, taking into account the optimal response from the agents, potentially with the local leaders moving before the general local population in a three-step model, or even the local elite moving before the funding agency.

Note that a core problem according to the literature will be that each local community will support their own leaders in the competition between villages for external funds, and in the process probably accept that the leaders take a share of the allocated funds. Such rent-seeking activities can in principle be minimised by use of objective targeting criteria and uniform programmes across villages. Programme uniformity will, however, conflict with the ideals of community involvement, where each village should come up with its own ideas for local development. The solution may be to allocate funds according to a pre-defined rule to avoid rent-seeking activities, but leave the villages to decide how to spend the funds.

But even if competition for external funds is minimised, the within-village competition for the distribution of funds will still exist. In response, the donors may attempt to side-track village leaders by working with NGOs or other community-based organisations (CBOs). But this may only move the political game to these organisations, with local leaders maneuvering to control the local NGOs and CBOs. As a result, attempting to adjust the power dynamics within a village is far from straightforward, and may not even be preferable, as it can be seen as an attempt to overrule local democracy. But in fact, community-driven development may in reality imply working with local leaders, and thus implicitly accepting that they receive their share of the funds. Some donors will, however, attempt to tilt the local balance of power by working with alternative local leaders, such as women’s groups, trade-unions, human rights groups, and other community organisations. Before we go on to the empirical literature, though, what can we learn from the formal modelling of these complex principal-agent relations?

Strategic aspects

It is useful to discuss in some detail the strategic relations between a donor agency, village leaders and the local population, where the latter may be split into a target and non-target group. The donor agency comes with a budget and normally some goals. In the simplest case the goal is to let the population decide how to spend the budget. In general, however, the donor will have more specific goals, such as poverty reduction. The latter requires that the target group of poor people is identified. The local population will want to benefit from the budget and realises that this may depend on coordination among themselves and the behavior of the donor and potentially the village leaders. The village leaders may care for the population as well as their own welfare. This all adds up to a very complicated game, with different interests within each group, potentially also within the donor agency. The outcome may depend on the sequence of decisions made by different actors, as indicated by the game-theoretic literature mentioned above.

The village leaders may first suggest a use of the budget, which within a CDD framework may then be discussed with the villagers before it is submitted to the donor agency. Or the donor may suggest a use of the budget that they discuss directly with the village population, which will then include the local leaders. The first will be a sequential game with three steps, the second a sequential game with two steps, where the village leaders and population need to coordinate in the second step. In both cases the first movers may take into account what they expect to happen in the following step(s). In theory one may also imagine that the villagers suggest a use of the budget that is sent either directly to the donor or via the local leaders.

In sequential games the last mover will normally lose, in particular if the first mover knows what the last mover will accept. In that case the first mover can offer as little as possible. If the first mover, such as an aid agency, cares about the last mover this may no longer be the case. This, in turn, implies that the donor may prefer to move first and suggest a use of the budget, which in turn is taken to the villagers, while taking into account that the local leaders may have different interests than the population. Meanwhile, in a proper CDD framework, one may imagine that villagers are allowed to move first and suggest a use of the budget. If village leaders are able to get involved in that decision, they may take a larger share than in the case where the donor agency suggests a budget.

Now this game has only described one village, but there may be competition between villages, so that the game is not only about the use of a fixed budget, but also a competition for the size of the budget. In this case the villagers may prefer to involve local leaders, as they may be better placed to negotiate a larger budget. Thus, for each village a CDD approach, where the villagers coordinate with the village leaders, is preferred to a standard model where the donor moves first. For the country at large, however, this may lead to rent-seeking activities where leaders from all villages compete for the total donor budget. This problem can be solved by the donor’s implementing simple allocation rules that do not allow for rent-seeking activities.

The conclusion is that a donor agency should not open up for costly negotiations about the distribution of funds within a country, but rather go for some simple allocation rules when it comes to the budget. This may still allow for local discussion of the within-village allocation of budgets. If villagers understand that the total budget does not depend on the efforts of the local leaders, then they may end up with more, say, in the final use of the money.

The final outcome may, however, depend on the degree of local control in the hands of local strongmen. The game we have described is part of a larger power game, and any surplus villagers gain from a programme can potentially be confiscated by other means. So a donor should take into account these broader power structures and attempt to find ways of strengthening the bargaining position of the poor and other marginalised groups. Again, strategic aspects are important: the donor should, for example, attempt to strengthen the outside option of villagers to make them less dependent on local strongmen. This may involve the transfer of assets, education, or credit and labor programmes that may provide villagers with an alternative to interactions with local employers and moneylenders. But in doing so the donor may have to take into account the local strongmen’s ability to hinder implementation of the development programme.

Empirical evidence

The strategic aspects discussed above imply that the outcome of any CDD programme will depend on the local context, in particular the internal power relations both at the village and national level, as well as the design of the programme. This in turn means that any impact evaluation of a particular programme has limited external validity. We will still discuss some findings, and with an attempt to keep the discussion of strategic elements in mind. The focus will be on fragile contexts. There are already other reviews, and we will to some extent rely on those here.

One CDD programme is the National Solidarity Project in Afghanistan. A large RCT was conducted to measure the impacts of the programme, which in turn led to a series of articles in top journals. These covered a number of outcome variables. The programme allocated block grants according to a pre-defined rule, which left the village to decide only on the allocation of those funds between projects. The RCT was designed to investigate precisely what we have discussed above, that is, allocation by way of local discussions (where local leaders may affect the outcome) versus direct decisions by the population (via a referendum). As expected, it was found that community discussions led to elite capture, while project implementation and welfare measures were not affected by the allocation method. That is, welfare improved equally in each setting, and compared to a (third) control group of villages there was progress on access to drinking water and electricity, acceptance of democratic processes, perceptions of economic well-being and attitudes towards women.

We also studied a similar programme implemented in Afghanistan with the help of a large RCT. That is, the Targeting the Ultra Poor programme. Our work builds upon a model implemented in a number of countries, which is found to lift people out of poverty, including in the longer run. The idea is that poor people face multiple constraints, and if all constraints are targeted at the same time, one can lift people permanently out of poverty. It also turned out that if one drops some of the programme components, then the programme may not work. The underlying constraints that keep people in a poverty trap are a combination of being initially poor (lack of assets, human capital, and collateral to raise loans) and market failures that result from a combination of people being initially poor and other underlying constraints (asymmetric information, large fixed costs) that limit competition and may leave people even without market access. Multifaceted programmes that target all these constraints at the same time will potentially help people out of poverty and may thus only need to run for a limited period of time. Similar to findings from other countries, in Afghanistan we found “significant and large impacts across all the primary pre-specified outcomes: consumption, assets, psychological well-being, total time spent working, financial inclusion, and women’s empowerment”.

The ultra-poor programme is not a full scale CDD programme, since the local community is not involved in the design of the programme. But it has a CDD component in terms of a Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) to identify the poor. And with the focus on village-level poverty traps, it is very much a community development programme and thus an alternative against which full-scale CDD programmes can be judged. Another similarity is that both programmes collaborated with the Community Development Council in each village.

A dramatically changed Afghanistan

The locations of these Norwegian-funded projects have undergone major military and political changes over the project period, culminating with the collapse of the Afghan government in August 2021. At the time when these projects started up, security had started to deteriorate, with the Taliban gaining a military hold and influence throughout northern Afghanistan, albeit less so in central Afghanistan. An increase in security incidents and civilian victims posed a major threat to travels and transport of commodities and sped up urban migration. Corruption took a firmer hold within the government (and NGOs). The realisation of the forthcoming international military downscaling or withdrawal and the potential for funding reduction led to an urgency for many among the Afghan elites to build up their personal reserves. In addition, Afghanistan was hit by a drought that reduced crops and income and caused internal displacement – followed by an unchecked Covid-19 pandemic.

By early 2021 the United Nations warned about a forthcoming human disaster and that increasing number of Afghans would end up in poverty. International donors’ withholding of development assistance after the Taliban’s takeover in August 2021 (financing 75% of the government budget in 2020) and the freezing of Afghanistan’s financial reserves led to a collapse of the Afghan economy and increased unemployment, poverty and humanitarian needs. Despite a partial lifting of US sanctions on individuals in the interim Taliban government, UN agencies and NGOs struggled to get funding into Afghanistan and to access funds held in Afghan banks. The Taliban administration on their side have neither been forthcoming in addressing concerns over governance and human rights, nor have they done much in the way of assuming responsibility for their own population. Restrictions imposed on girls’ education and women’s access to work and movement are especially damaging for Afghan development, now and in the future. Continued or increased gendered restrictions are likely to further increase the tension between the Taliban administration and the international communities, including the UN’s and NGOs’ ability to operate and provide services to the Afghan population.

A practical challenge noted from the interviews was that some of the international NGOs and UN agencies had their international staff evacuated in August, and it took them some time to get these people back to Kabul and to re-establish their operations. Several directors and key staff of Afghan NGOs had either been evacuated or had decided to leave Afghanistan, reducing their ability to operate and continue their activities. This was a particular challenge for the Norwegian Church Aid that prioritises working through national NGOs, who also had experienced severe restrictions on accessing project funding deposited in Afghan banks.

The humanitarian disaster and uncertainty influenced the situation in the provinces and districts selected for this review’s fieldwork, and thus interviewees’ concerns and priorities as well. To situate the field findings, we therefore provide a brief presentation of the areas visited and what the interviews brought out about security, governance and humanitarian conditions.

Faryab, with its mixed Pashtun and Uzbek population, was an arena of armed struggle between the Taliban and the Afghan government and of internally and ethnically driven divisions that at times were linked to power struggles in the Afghan government. The government used military force to extradite an influential Uzbek who opposed the Ghani government before the 2019 Presidential elections. The Uzbeks responded by refusing a Ghani government-appointed (Pashtun) governor in spring 2021. In the meantime, the Taliban had taken a firmer grip on rural areas, set up their parallel administrations and demanded NGOs relate to them. The provincial capital Maimane fell to the Taliban a few days before Kabul, and they installed local Uzbek and Pashtun Taliban members in central positions in the administration, even though many of the administrative staff of the former government remained in their positions. The NGOs operating in Faryab had over time adapted to regulations and restrictions imposed by the Taliban in areas under their control, while finding ways to uphold projects for girls and women and the ability for their own female staff to work and travel to the field. While more cautious in their approach they had by the time of the fieldwork not experienced restrictions on their programming.

By late 2021 the field research found the warfare had abated and the populations reported an improved security situation. While the population spoke positively about the Taliban administration, there was a noted uncertainty over their ability to govern and support the population.

The field research included a report of a dire humanitarian situation in Maimane, primarily caused by the drought, that has caused lack of food and very high unemployment. A survey PTRO conducted for another research project in the Maimane and Qaisar districts of Faryab found that the:

… majority of the respondents (79%) said they have received loans from relatives and friends, 40% said they have sold household belongings including livestock, and approximately 24% of respondents said their family members have migrated abroad with hopes of sending resources back home, and 18% reported internal migration of their family members.

The job migration was primarily to Iran, which traditionally has offered low-paying jobs to legal and illegal immigrants in the agricultural and building sectors. A sizable number of the recent migrants planned to move on to Turkey with a hope of reaching Europe.

Badakhshan is predominantly Tadjik inhabited, with some parts difficult to access due to mountains, and therefore the people are relatively poor. Small-scale mining and smuggling generated income, and different parties struggled to control the income. The Taliban historically never managed to gain an influence in the province or to control it militarily. However, over the last years they did manage to establish a presence in the province, thanks to a combination of inclusion of Tajiks in their ranks and the exploitation of the opposition against the Ghani government. During spring 2021 the local administration’s crackdown on protesters increased tensions, leading central members of the administration to flee to Kabul and thereby ease the Taliban’s military takeover. The Taliban installed Tadjik Taliban in central positions in the administration, with many of the administrative staff of the former government remaining in their positions. NGOs with strong communal anchoring and support had by the time of the fieldwork not had any restrictions imposed by the new administration.

By late 2021 the warfare had largely ended, and the population reported on improved security due to the absence of local milits/arbaki that had previously engaged in fighting and looting. However, many interviewed were uncertain about the Taliban’s willingness and ability to provide them basic services and about whether the Taliban would engage in the same corrupt practises as the previous government.

Badakhshan reported the same dire humanitarian situation as in Faryab, with a lack of food and very high unemployment.

These crises had led to increased male labour migration to Iran, with some considering travelling further on to Turkey. Relatives were cautious about the prospect for remittances. The low wages paid in Iran could have a labourer work for one year to cover the fees paid to the human smugglers if they were not returned earlier as a result of being caught as illegal migrants.

Ghazni province is divided into a Pashtun south and a Hazara north (where Jaghori is located), where borders and grazing lands have been the subject of historical conflicts. Many Hazaras have traditionally migrated for protection and work, there is a sizable population in Quetta in Pakistan, and many seek job opportunities in Iran. The Jaghori area stands out with high education levels, including for girls, and good health services as prominent representatives managed to attract international (and Norwegian) funding for schools and a hospital. Many from Jaghori reside internationally, and remittances represent a major source of income for the population. Hazaras are shias, and they have been subject to oppression and massacres by successive regimes throughout history, including from the Taliban. The Taliban gained very limited influence in Hazara areas but recruited some Hazaras to their ranks. There was, however, a negotiated surrender to the Taliban in August 2021, though many Hazaras left for Pakistan and Iran for fear of persecution. In contrast to Faryab and Badakhshan, the Taliban installed a Pashtun district administrator in Jaghori, though with a Hazara deputy. This led to major differences between how restrictions on women’s access to employment, income and acceptance was handled in different parts of Ghazni, as reported by Human Rights Watch.

By late 2021 the field research found respondents reporting a high level of security, but some targeted killings a few months ago made people uncertain about the future and led them to keep a distance from the new and unfamiliar authorities.

Drought and lack of drinking water was found to be more severe than in previous years and became a main reason for internal migrations and for people leaving to seek jobs in Iran. Migration to Iran had increased following the Taliban’s takeover, and many reported depending on remittances from family members residing in Europe, Australia, the US – and Norway.

Food is available in the market, but the devaluation of the Afghani has increased prices.

An observation from all three locations was that the Taliban administration had a positive and accommodating attitude towards the NGOs included in this review. There fieldwork found no reports of limitations imposed on projects for girls or women, or limitations on female staff’s work – except the demand for an accompanying male relative when travelling on to the districts, which many NGOs had practiced for years in Taliban-controlled areas. Afghan NGOs were, however, more uncertain over the future and types of projects they could engage in than the international NGOs were

Community-driven development in Afghanistan

The Community Development Councils (CDC) were introduced with the National Solidarity Projects (NSP) back in 2003. The project was implemented by the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) and initially financed by a consortium of international donors coordinated by the World Bank, later through the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF). While the idea for the NSP built on experiences from Indonesia, the respective ministers of Finance (Ashraf Ghani) and MRRD (Haneef Atmar) tailored it to the ongoing Afghan state-building project. The CDC was planned as the lowest level of the Afghan government structure, though that authority was never approved by the Parliament.

The CDC formation built on the traditional and usually all-male Afghan village councils that through internal processes were tasked with management of communal resources, such as distributing water for rain-fed land and managing grazing areas, or organising voluntary work for maintenance of water canals, roads, the community mosque or the school. Many villagers and districts had an influential and often rich person/family that could host meetings, provide visitors with food and lodging, and be the contact point with the government. These were frequently referred to as the Arbab or the Malik in the village or the Khan at the district level or in the tribal structure representing a number of villages in a district. From the late 1980s, NGOs and later the UN organisations shifted their rehabilitation assistance from being channelled through the mujahedeen commanders to the more traditional village council structures, often referred to as the village shura (an adapted military term for “council”). After that, some NGOs and organisations engaged with the traditional village councils, while others established their own structures.

The CDC concept moved beyond project delivery as it aimed to modernise and formalise communal governance and bypass the traditional village headmen and the mujahedeen commanders (if they were not one in the same). CDCs did this by introducing secret ballot elections (done before national elections to ensure acceptance of democratic processes), demanding female representation (to shape attitudes toward women) and providing administrative training and bookkeeping. The aim was that women either were represented in mixed-gender CDCs, had their separate CDC with a joint executive committee, or were members of “women working groups” in communities with social restrictions on female public participation. The third phase of the NSP programme (2010-2014) placed more emphasis on governance and gender equality and encouraged communities with separate male and female CDCs to integrate these into one. However, in practise many mixed CDCs did not have joint meetings and instead the female deputy leader (typically a female relative of the leader) would relay women members’ concerns to the male CDC head. A study of the CDC and traditional shura function in the Qarabagh area north of Kabul noticed that:

… the NSP represented a joint held vision, by the central government and international actors, that would offer an alternative to traditional governing practices at the village level. The CDCs were considered ‘modern’ because their representatives were elected and not approved through familiar ties or other patronage networks, as was the case with customary shuras.

There was an aim for regular re-elections to help exclude non-functional council members. An observation from a senior government official was the following (interview 14.02.2022):

Success and failure of CDCs could be attributed to the NGO facilitating partners and their capacities and their commitment to development.

A bidding process was used to select the international and Afghan NGOs’ facilitating agencies, tasked with the formation, training and facilitation of CDCs in the different provinces. This included development of a Community Development Plan (CDP) and prioritisation of projects for the block-funds set aside for each village. The CDCs were used to channel new NSP block grants to the villages and to provide management contact with assistance from other ministries or NGOs. The structure was developed further with District Community Councils (DCC), with representation from all CDCs and structured to coordinate their activities. The Afghanistan’s Citizens’ Charter Programme (CCAP) introduced in 2016 included urban areas and aimed to combine and coordinate efforts between the different Ministries to “empower communities for better services”.

A number of sources and interviews point to a gradual weakening of the government-established CDCs, despite attempts to revive them through the Citizens’ Charter. Some raise questions about whether all of the facilitating partners were sufficiently qualified for the task of establishing and guiding the CDCs, which led to large differences between their capacities and skills.

One reason for the weakening of the CDCs was that the already existing “local shura” with a traditional leadership (elders, respected community members and religious leaders, as noted in Qarabagh) often continued in parallel with the CDC, with members possibly on several (or all) village councils.

Another reason was that more influential villagers re-established their influence over the CDC following the first round of elections, and then prioritised external funding for their own/family/network purposes. In Qarabagh this kind of move was moreover reported as a way to counter Kabul’s effort to “diminish the authority of local communities”.

However, Afghan researchers point out that realities on the ground are more nuanced. The social structures have significantly changed in the last 10 years in Taliban-controlled areas. Many of the influential tribal elders left or were forced to leave the area to provide the Taliban with space to impose their control. Most of the local Taliban leadership comes from families without a history of any tribal influence, and therefore they see the influential tribal elders as a threat to their power in the villages. This also goes for the maliks, CDC members and others involved in bringing aid to the Taliban control areas, who have subsequently shared resources with local Taliban.

Many of the influential tribal leaders benefitted from running businesses, construction companies, or were employed in government or other national and international organisations. Many of these were not interested in seeking benefits from aid coming to their communities, but would rather have an interest in assistance reaching the poor they would be expected to support. These tribal leaders are currently exploring possibilities to regain their lost influence and position in communities they regard as their constituencies. This dynamic goes against the interests of Taliban local leaders, their district officials and the corrupt village elders, and the NGOs can easily end up caught between these conflicting interests.

The third, and related reason, that the CDCs lost power and influence over time was the high level of corruption that gradually crept into the MRRD and NSP (and later Citizens’ Charter) programmes from the leadership all the way down to the villages. The result was, according one source, that towards the end of NSP project “many CDCs only received 10% of the project funding budgeted for them” (email exchange 04.02.2022).

A fourth reason was that several of the NGOs did not use or only partially used the CDC structure when implementing projects funded outside the NSP and Citizens’ Charter programmes. Some NGOs established village committees for their particular projects or limited their consultation to the more powerful members of the village.

As the Taliban gradually established its influence and control over the countryside, it entered a symbiosis with the government structures that continued to provide basic services such as education, health and community development. NGOs and UN organisations were left with few other options than to relate to the local Taliban committees if they wanted projects to be continued or if they wished to enter new areas. In an interview in 2020 a national staff member of an international NGO summarised their dilemma in a norther province in the following way: “the Government demand a bribe to allow us to assist people in Taliban controlled areas, and the Taliban impose a tax upon us for us to work there, leaving less funding for the villagers”.

Organisation and project overview

The five NGOs funded by the Norwegian MFA and NORAD are ACTED, DACAAR, NAC, NCA and NRC. While the main focus early on was on the Faryab province, the NGOs also implement Norwegian-funded projects in a number of other provinces, as Sar -e Pul, Daikundi, Samangan, Badakhshan, Ghazni, Khost and Kabul. There is quite a large span of activities and variation in how each organisation engages with community organisations. One major difference is that while Norwegian Church Aid works with, enables and channels funding through Afghan NGOs, the other NGOs self-implement their aid efforts.

The total reported budget in Norwegian Kroner (NOK) for the period 2018 to 2021/2022 is ACTED: 180 mill. (MFA); DACAAR: 78 mill. (MFA); NAC 99,1 mill. (MFA/NORAD); NCA: 49,5 mill. (MFA, NORAD and DIKU) and NRC 235 mill (MFA/NORAD). We have for this review concentrated efforts on what can be defined as rural or community development projects.

Below is a brief description of the five NGOs supported, and their projects.

ACTED is a French NGO, started in Pakistan/Afghanistan in the early 1990s and registered in Kabul in 1993, later to work internationally. ACTED has from the start advocated for a manteqa (district) approach through a set of manteqa shuras, rather than a more selective approach to a single village or a number of villages. Their aim is to support a diverse range community development projects and foster collaboration within the manteqa, based on identified needs. Their model resembles the District Development Council, with representation from, on average, 10 village councils and includes more specialised committees, such as school management committees, water user groups, women farmer groups and breeder cooperatives. ACTED was Facilitating Partner in the National Solidarity Programme.

ACTED’s projects were located in Faryab, Jawzjan, Balkh and Samangan Provinces, and in Faryab they did work in the following districts: Andkhoy, Dawlatabad, Sherin Tagab, Khwaja Sabz Push, Almar, Qaisar, Maimana, Kohistan and Pashtoonkot.

Their AGORA research unit established a manteqa profile, undertook a vulnerability assessment and developed training and development plans. Training was provided for local government staff, community workers and CSO staff, followed by delivery of block grants.

Among activities were:

- Literacy and education courses, local schools support, Kankoor courses and student scholarships.

- Youth development centres, with teachers and activities.

- Vocational training centres.

- Off-farm job creation, with apprentices and emphasising women business development.

- Irrigation infrastructure and social water management.

- Agricultural productivity and value chain support, including support for agro-cooperatives and women farmer groups, with an emphasis on sustainable agriculture and marketing and extension services.

- Livestock and veterinary services, including animal vaccination, support for poultry farms and breeder cooperatives.

- Local market development, with agro-fairs and establishment of a price information system.

ACTED aimed for 50% female beneficiaries, hired local female staff and secured women’s involvement in the Manteqa structure. They had a priority for projects targeting women, internships for women and establishment of female CSOs and women farmers groups.

They reported problems with establishing female agro-farmers cooperatives, especially in Faryab province, and poultry backyards in Qaisar.

ACTED informed us that they have a system in place for internal monitoring of their projects, a Manteqa Compliance Units, and they draw on the AGORA programme research unit for evaluations.

DACAAR is a Danish Afghanistan-focused NGO that started to assist Afghan refugees in Pakistan in 1984. DACAAR started with a sewing project for women and then moved into water supply and production of water pumps before moving inside Afghanistan from 1989 with construction and rehabilitation activities. DACAAR has throughout maintained their expertise on WASH, women’s empowerment, and engineering and agricultural activities. DACAAR was Facilitating Partner in the Citizens’ Charter project, facilitating establishment of CDCs and sub-committees. In addition to engaging with the CDCs (including female CDCs) and DDAs, they established water user groups, water management committees, women’s resource centres, irrigation management committees and saffron producer associations. DACAAR maintains that they focus on most at-risk groups such as women and youth-headed households, farmers with little or no land, the elderly, the disabled and those marginalised by society.

Their Norwegian-funded activities in the Faryab province took place in Maimana, Pashtoonkot, Khwaja Sabz Push, Sherin Tagab, Dawlatabad, Andkhoy, Qaisar and Almar districts.

DACAAR had four main project activities:

- Durable access to safe water and improved hygiene and sanitation behaviour change.

- Improved and sustainable increases in agricultural/livestock production for male and female farmers.

- Improved and sustainable business and employment opportunities for unemployed youth and farmers (male and female).

- Improved and sustainable social and economic opportunities for vulnerable women.

DACAAR informed that they run base- and end-line surveys for their projects, have an M&E framework and trained staff (including female staff) for this purpose, an Internal Audit Unit and contract with external evaluators for mid-term reviews (Tagheer in 2017) and evaluations (NCG and Tadbeer in 2020).

NAC is a Norwegian NGO focused on Afghanistan, established in 1979 following the Soviet invasion. They operated medical teams and provided cross-border assistance from Pakistan, before moving into rehabilitation and integrated development projects from 1989 and establishing an office in Kabul in the mid-1990s. NAC has a high priority on gender, with an emphasis on health and education projects.

NAC emerged as the NGO that has worked most deliberately with the CDC structure and involves the councils from the very start to ensure the sustainability of their projects. However, they have gone further and extended the role and influences of community governance structures (not only the councils) into their programming. CDCs were initially planned to have two sub-committees, one on education and one on health, but based on NAC advice during the development of the Citizens Charter Afghanistan Programme for Jaghori, there are now seven CDC sub-committees (as per CCAP guidelines). And in Jaghori, NAC expanded the inclusion (and influence) of other groups and community representatives (such as elders, religious leaders, women, and youth) in the governance and community development processes.

NAC ran Norwegian-funded projects in the Badakhshan, Ghazni, Kabul, Khost, Nangarhar, Paktia, Takhar, and Faryab provinces, in the latter with activities in Maimana, Khwaja Sabz Posh, and Shirin Tagab districts.

The NAC project is titled Empowering Rural Afghan Communities (ERA), and includes the following components:

- Education, including support for children in government schools: early childhood development, upgrading of teachers to diploma level, core competency programmes, innovative teaching and learning methodologies, disability inclusion, students’ parliament, strengthening of school schuras, capacity building of MoE staff, Technical and Vocational Education (TVET), Life and Livelihood skills for Women, and Education in Emergencies (in Faryab).

- Food security and work, including capacity building of agricultural officials and lead farmers, with a focus on increases in agricultural production, and self-help groups for women.

- Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and climate change, including school-, community- and district-based Emergency Relief teams, tree planting, community-based interventions, building capacities among district and province authorities in Badakhshan and Ghazni, preparing and responding to drought.

- Health, including training of midwifes and health nurses, training of community-based female (and male) health workers (CHWs), mobile clinics (in Paktia), women-owned and -run maternal and newborn health Centers (CCCs), as well as capacity building of MOPH staff, Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences (GIHS), and support for association of Afghan healthcare professionals.

- Conflict transformation and dialogue (Badakhshan, Faryab, and Ghazni) – Peace-day celebration in Faryab, and dialogue methodology applied to problem-solving at Institute of Health Sciences.

NAC reports that they undertake base and end-line surveys for their projects, they have an internal M&E system and made use of external evaluations and midline reviews (see i.e., 2021 report).

NCA is an internationally oriented Norwegian NGO with a consistent engagement with Afghans since 1979. Initially NCA provided support to refugees in Pakistan and some cross-border support in collaboration with NRC. From 1993 more of the activities shifted to inside Afghanistan, going into rehabilitation, women’s empowerment, rural development and peacebuilding. In 2020 NCA initiated a national-level peace dialogue and formation of a national Peace Building Working Group (PBWG) with 54 member NGOs and development of a national action plan for peace. NCA works primarily with and through Afghan partner NGOs, building their capacity and monitoring and evaluating their planned activities. NCA partner NGOs were Rural Rehabilitation Association for Afghanistan (RRAA); Sanayee Development Organisation (SDO) (these are discontinued in 2022); Afghan Development Association (ADA); Afghanistan Women Educational Centre (AWEC); Afghanistan Women’s Skills Development Centre (AWSDC); Central Afghanistan Welfare Committee (CAWC); Citizen Organization Advocacy and Resilient (CoAR); Organization for Relief Development (ORD) and Organization for Research and Community Development (ORCD). These partners, several of which were Facilitating Partners for the NSP and Citizens’ Charter programmes, work through CDCs or more specialised committees, such as female and male Peace Shuras.

NCA reports that they support projects in Faryab, Daikundi, Samangan, Khost, Kabul and Badakhshan provinces. For this review NCA suggested we review AWEC’s projects in Badakhshan as none of the other partners NGOs had ongoing activities in Faryab. It turned out that several of AWEC’s projects were funded from sources other than the programme under review.

Their main programme with NORAD funding, titled Building Resilient Communities, had the following components:

- Peacebuilding, including 1) inclusive, gender-sensitive peacebuilding; 2) shuras and mechanisms to prevent and transform conflicts; 3) increasing women’s participation in peacebuilding processes; and 4) social group experiences with constructive inter- and intragroup relations.

- Economic Empowerment, including 1) enabling men, women and youth to establish micro and small enterprises; 2) vocational skill training and support to enable youth (male and female) to secure sustainable employment; and 3) increasing profits and productivity of men, women and youth through value chain development.

- WASH projects, including 1) having communities demonstrate ownership of WASH services; 2) having duty bearers integrate women’s and men’s recommendations into their plans; 3) having women, men, girls and boys practice hygiene measures that protect against key public health risks; 4) providing women, men, girls and boys with access to adequate and sustainable sanitation services in their households; and, 5) ensuring that women, men, girls and boys have access to sustainable, sound and minimum basic water supply services for domestic purposes.

- Climate Smart Economic Empowerment (CSEE) addressing 1) youth unemployment, 2) climate change and 3) food insecurity by increasing people’s access to climate smart food production systems, jobs, and other income opportunities.

NCA moreover supported 1) community-based drug rehabilitation through the Nejrat Centre; 2) peacebuilding through inclusive and improved ethnic and tribal relationships; and 3) The Social Council for Consolidation of Peace (SCCP), previously known as the Religious Actors for Peace (RAP) programme with Sanayee Development Organisation, 4) provision of Protection and Wash Services to IDPS in Kunduz and Badakhshan with Afghanistan Women Educational Centre (AWEC) and Afghan Women Skills Development Centre (AWSDC).

The different reports submitted include a number of NCA and partners monitoring reports, and mid-term reviews and evaluations conducted by external consultants.

NRC is an internationally oriented Norwegian NGO with an engagement for Afghans since 1979. The engagement started with support for refugees in Pakistan and later also Iran, combined with some cross-border support into Afghanistan. NRC withdrew from their partnership with NCA in 1994 but returned in 2003, and is currently a leading NGO providing support and legal assistance for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). NRC places a strong emphasis on protection of vulnerable populations and gender-sensitive programming.

NRC reports that they utilise CDCs and other communal representative structures, such as shura and school committees, and individuals, as local and religious leaders, in their programming.

The projects covered by this review include the following:

- Education, including community-based education (CBE), Accelerated Learning Classes (ALP), Education First Phase Response (for displaced) (EFPR), Better Learning Programme (for youth) (BLP) and Education in Emergencies (EiE).

- Information, Counselling and Legal Assistance, ICLA, for IDPs to obtain identity documentation, address their needs and disputes and provide access to essential services.

- Urban displacement out of Camp (UDOC) addresses displaced people living with host communities, particularly in urban environments, with provision of some camp management core functions.

Projects are implemented in the Faryab, Kunduz and Sar e Pul provinces.

NRC has a self-monitoring system in place for their projects and utilises external evaluators to review their projects.

Comparing NGO approaches

All NGOs in this review have a strategy to work with community organisations, from identifying the needs to respond to, organise the work, mobilise community resources, monitor implementation and sustain activities. How each NGO does these things, however, varies a lot, and we address these differences below where we draw extensively on the fieldwork findings.

However, to frame such a discussion let us first revisit some of the assumptions about the role of and engagement with different types of community-based organisations. Here it is important to keep in mind the Afghan government’s (and the donors’) investment in and funding of the CDCs and later the District Councils that have a presence throughout Afghanistan, though such councils were not necessarily continued or re-elected when the external funding came to an end.

One major difference in approach, as is identified in the literature on community development, has to do with whether the funding/implementing agency (or government) takes a minimalist approach and primarily views the community organisation or specialised committees as a vehicle for project implementation. Such an approach is arguably a more appropriate approach to more specialised or short-term activities. It can, drawing on Katz, be termed community-based development.

Alternatively, the funding/implementing agency may take more of a maximalist approach with an aim to develop and empower an organisation that on its own (or with external assistance) can plan, mobilise resources, implement projects and maintain and sustain investments in a manner that a majority of the community members accepts. This second kind of approach coordinates and intertwines readily with government planning, provision of basic services to the population and governance more generally.

The first approach can be more to complement, for a shorter period of time, a possible lack of government provision or a government’s inability (on its own) to provide such services or to govern effectively. The latter approach is more resource- and time- consuming and requires the sustained presence of an external agency in an area for a longer period, as well as a fairly stable security and migration situation. Insecurity and job- and drought-related migration have posed greater and greater challenges in several areas of Afghanistan over the last years, certainly in the Faryab province where most of the projects were implemented.

In an impoverished community, a position on any type of community body tasked with prioritisation and distribution of resources can allow one the chance to prioritise such resources for their own or their family’s/network’s benefit. The CDC concept with election of representatives (possibly separate female CDCs) was meant to mitigate possible domination from individuals and ensure representation of women and minorities. However, that was frequently not the case, or the community bodies were “recaptured” by influential individuals, as the literature and this review has documented. The traditional community councils can be equally prone to misuse and majority/male dominance, although communities can also mitigate such challenges (as they have done for centuries) by securing over time the inclusion of respected community members, such as elders, educated or religious leaders, who can help maintain community control. Women are more seldom included though, except in areas with that being accepted and practised.

ACTED’s 2019 Baseline Assessment: Household Component documents wide variation in communities’ knowledge about and engagement in councils and development planning and activities. They identified a higher degree of knowledge and a more positive attitude in urban areas and among men, compared to in rural areas and among women. While ACTED collected its data in areas benefitting from ACTED’s support, we might assume that the response to some of the key questions will be relevant to other areas and organisations:

- When community-level meetings were held to discuss development planning in their area only 34% of households in general were aware that they were happening, but only 15% of the female-headed households said that they were.

- When asked if their input to community-level discussions was taken into account, 18% of all households indicated that it was, while only 6% of the female-headed households did.

- When asked if they considered local accountability mechanisms to be effective, 37% of all households supported that claim, but only 13% of female-headed households did.

- Asked if the local development planning processes were participative, 53% said that they were, but only 20% of female-headed households supported that claim.

- When asked if they planned to attend community-led meetings for development planning in the coming year, 32% overall confirmed that they were so planning, but only 10% of the female-headed households did.

The field researchers had two important observations that need to be kept in mind when analysing the interviews with the community representatives and the beneficiaries, which led them to seek additional local sources of information:

- Communities were reluctant to be openly critical of the new Taliban administration, although there were differences across various provinces and districts, depending on history and the qualifications and reputations of the Taliban-appointed administrators.