EFFEXT Background Paper – National and international migration policy in Ethiopia

2.1.1. Government Policies and Regulations

The Overseas Employment Proclamation

Prevention and suppression of trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants proclamation

2.2.1. Policies and Regulations

2.4. Migration Governance Structure

3. Regional Context: IGAD States

This EFFEXT Background Paper provides a brief presentation of migration and migration policy dynamics in Ethiopia. It presents an overview of key national and international migration policies, and outlines the key migration governance structures in Ethiopia. In terms of international relations, the paper primarily focuses on regional and European collaboration. The Background Paper concludes with a short reflection on key questions that need to be explored when studying the effects of EU migration management in Ethiopia.

The Effects of Externalisation: EU Migration Management in Africa and the Middle East (EFFEXT) project examines the effects of the EU’s external migration management policies by zooming in on six countries: Jordan, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Senegal, Ghana and Libya. The countries represent origin, transit and destination countries for mixed migration flows, and differ in terms of governance practices, state capacities, colonial histories, economic development and migration contexts. Bringing together scholars working on different case countries and aspects of the migration policy puzzle, the EFFEXT project explores the broader landscape of migration policy in Africa and the Middle East.

The EFFEXT Background Papers guide the fieldwork, case selection and analysis of migration policy effects in the EFFEXT project’s case countries. The papers are based on desk-reviews of scientific literature and grey literature, the latter including government documents, governmental and non-governmental reports, white papers and working papers.

Introduction

Ethiopia has been praised as one of the top host countries for refugees in Africa. As of February 2022, Ethiopia hosts 837,533 refugees from 26 different countries including Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Yemen, Syria, Congo, Burundi, Djibouti, and Rwanda (UNHCR 2022). The country is also one of the main sources of migrants from the Horn of Africa with an international migration rate of 1.1% (1,072,900) in 2015.[1] Although this is lower than the sub-Saharan average of 2.5%, migration from Ethiopia has increased in recent years (Asnake and Fana 2021).

The pattern of movement of both Ethiopian migrants and refugees, the majority of whom travel through irregular channels, has been complex and evolved over time. This has resulted in concern from many actors, particularly in government and the international community, about the need to ‘regulate’ and ‘manage’ mobility from and to Ethiopia (Kiya 2021). In response, different legal and policy instruments have been established at the national and regional levels that have been the basic pillars for the management of international migration by the Ethiopian government and other concerned stakeholders. This emerging policy architecture is the outcome of the interaction of multiple interests within and external to Ethiopia (AMDPC 2021). The EU has been particularly active in supporting the development of migration management. What is not known is how the policy outcomes have been affected by these external interventions.

This background paper aims to provide a background to the legal and institutional frameworks put in place in response to international migration from and to Ethiopia. The review maps out key existing policies adopted by national governments, regional organisations and the EU that aim to respond to migration issues while addressing how this affects the relation between the EU, IGAD (Intergovernmental Authority on Development), and Ethiopia. First, the report gives a brief background on Ethiopia’s national migration policy. This is followed by a presentation of the national migration machinery and governing structure. The next section presents the regional context, with a focus on IGAD and regional commitments. Subsequently, the last section gives an assessment of EU-Ethiopia migration policy relations.

National Migration Policy

2.1. Ethiopian Migrants

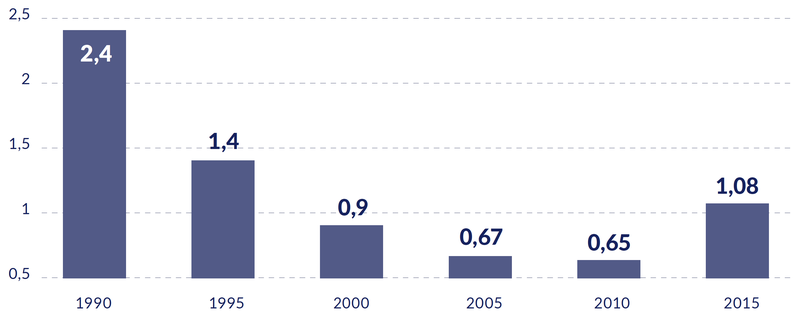

Existing data on migration from Ethiopia has failed to provide a clear picture of the magnitude, trends, and profile of the migrants because of lack of reliable data and the most often irregular nature of movement of people from or to the country. In 2015, as compared to other Sub-Saharan countries, Ethiopia had a low emigration rate of 1.1% (World Bank 2022). The country’s emigrant population has remained below 1% for over a decade (see figure one).

Figure 1: International migrant stock (% of population) – Ethiopia (World Bank 2022)

Migration from Ethiopia has been fuelled mainly by socio-economic and political factors. Drivers of migration include un- and under-employment, unstable employment, job insecurity, inflation, poverty, lack of affordable housing, poor infrastructure provision, corruption and lack of good governance, land shortage, land fragmentation meaning that small plots of land are left for individual cultivation (Guday and Kiya 2013). There are a considerable number of migrants who leave the country for political reasons and many leave due to ethnic discrimination, political insecurity, and persecution (RMMS 2014). Migration in Ethiopia is also driven by social and cultural reasons, particularly for women. These reasons include early marriage, flight from divorce, marital problems, conflict with parents, and sexual abuse (Jones et al. 2014). Failure in national examinations, enticements from smugglers/traffickers and peer pressure are also indicated as drivers of migration (Kiya 2021).

Research has found that in some parts of Ethiopia a ‘culture of migration’ has been established. The youth mainly is expected to migrate and provide for the family or gain a social status that comes along with being a family of a migrant. The social prestige is also extended to the individual migrant for becoming part of a diaspora (RMMS 2016; Horwood 2015; Guday and Kiya 2013). Globalization or glocalization has also been forwarded as a driver of youth migration from Ethiopia: the expansion of technologies and the internet, and the resulting flow of information, has led to increased migration among the youth as they realize their aspirations (Asnake and Fana 2021).

According to IOM, more than 839,000 Ethiopians have migrated to other countries in the past five years in search of job and economic opportunities.[2] The majority of migrants prefer irregular channels for different reasons, however, restricted access to formal channels of migration accounts for the majority. Further, the irregular channel is less bureaucratic and time consuming, cheaper and more rewarding, which makes it more appealing to migrants (RMMS 2016). According to a RMMS study conducted in 2014, only 40% of Ethiopian migrants, mainly women, leave the country through the regular channel (RMMS 2014).

There are three main migration routes identified in the literature: the southern, eastern, and northern routes. However, these routes are not clearly defined and change constantly in response to border control measures and government action against irregular migration. The eastern route, which most migrants use, runs through Somalia and Djibouti with a destination to the Middle East countries, among which are Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Lebanon (Lindgren, Uaumnuay, and Emmons 2018). Ethiopians reportedly account for more than 80% of the 365,000 migrants that arrived in Yemen between 2008 and 2016 (RMMS 2016). The southern route, through Moyale, goes all the way to the Republic of South Africa. A report by Yordanos and Tanya (2020) indicated that Ethiopians are among the largest group of asylum seekers in South Africa, with an IOM estimation of 65,000 – 70,000 Ethiopians migrating to the country in 2009. The northern (sometimes called the western route) is used by migrants whose destination is Sudan, Egypt, Libya and Europe. Between 2017 and 2018, the number of ‘legal’ migrants crossing the border daily totalled an average of 95, based on the number of travellers the Ethiopian immigration office accommodated every day (Kiya 2021).

Along these routes, a large portion of the migrants are women, showing an increase from 47.3% in 2000 to 49.1% in 2017. Female migrants particularly dominate the eastern route, following the demand for housemaids in Middle East countries (Asnake and Zerihun 2015). Meanwhile, young male migrants dominate the route to Europe and the Republic of South Africa (RSA) (Yordanos 2015).

There are also a significant number of seasonal labourers, dominated by male migrants. There is seasonal labour migration to Sudan, particularly to the eastern part, to work on agricultural plantations. Seasonal migrants travel mostly during the different farming seasons (planting and harvesting) to work on large-scale plantations and farmlands both on the Ethiopian and Sudanese side of the border, mainly harvesting cotton, sesame and sorghum. They are mostly male migrants, aged 18 to 35, however their exact number is unknown since most make their way to Sudan illegally (Kiya 2021).

According to a report by GIZ, an estimated 80,000 daily labourers cross the border every year in search of work in Sudan (GIZ 2018). Eldin and Ferede (2018), however, estimate a much higher number of half a million Ethiopian seasonal labour migrants per year. The adjacent Gedarif State, where labour demand for farm work is high, has become a destination for most labourers. Their movement, however, lacks any legal procedure which puts them at risk from employers, border officials and law-enforcement bodies, or fellow labourers. Regardless, this type of movement “has become a stable livelihood basis both to Ethiopian families and to the sustainability of farming and agricultural production in Sudan” (GIZ 2018).

There is also labour migration to Ethiopia, that is mainly characterised by high skilled expatriates working in organisations. Work permits are issued to limited skill levels so as not to disadvantage nationals. Migrants from Asia, mainly China, dominate the labour market; of the 20,689 work permits issued during the year from July 2015 to July 2016, 90.5% were for workers from Asia and 63.07% for Chinese nationals. The majority of these workers are engaged in the construction and manufacturing sector: 55.24% and 16.7% respectively (ILO 2020).

2.1.1. Government Policies and Regulations

To ‘manage’ all these different types of migrants, the Ethiopian government has established legal frameworks, most of which have been focusing on irregular migration, human trafficking and smuggling. The term ‘migration management’ refers to “numerous governmental functions within a national system for the orderly and humane management for cross-border migration, particularly managing the entry and presence of foreigners within the borders of the State and the protection of refugees and others in need of protection".[3] Similar to what Tinajero (2014) finds in the case of Italy, the approach taken by Ethiopia in managing migration is to control migration and labour mobility. In this regard, migration management refers to controlling and putting an end to irregular mobility of individuals across international borders rather than planning an approach towards orderly migration.

The Overseas Employment Proclamation

The Overseas Employment Proclamation (923/2016) is among the national legislations that attempts to ‘regulate’ migration from Ethiopia. In response to the growing number of labour migrants from Ethiopia and the rise in reports of abuse against Ethiopian migrants, the Employment Exchange Service Proclamation 632/2009[4] was revised into the Overseas Employment Proclamation (923/2016).[5] The revision of the proclamation followed the ban of labour migration to the Middle East by the Ethiopian government in October 2013, as a result of increasing reports of abuse of Ethiopian migrants faced in the Middle East countries. The proclamation aimed at providing protection to labour migrants and regulating overseas employment of Ethiopian nationals. However, the proclamation is restricted to unskilled labour migrants traveling to the Middle East through private employment agencies (PEAs).

The 2016 proclamation requested bilateral labour agreement (BLA) between Ethiopia and receiving countries. At present Ethiopia has BLAs with Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The BLAs specify the working conditions of migrant workers and the necessary conditions for Ethiopian labour migrants to work in the respective countries. The proclamation further states pre-departure training as a requirement. These include pre-employment and pre-departure awareness raising on the conditions of destination countries, the required skill for a job, and rights and duties. Migrants are expected to meet all the necessary qualifications, which includes completing training, have a grade eight education, and a certificate of educational competence.

The Overseas Employment Proclamation 923/2016 permits three types of overseas recruitment:

- recruitment through public employment services, based on intergovernmental agreements;

(2) recruitment through PEAs;

(3) direct employment. In any of the recruitment mechanisms, a written employment contract approved by the Ministry of Labor and Skills (MoLS) is required.

MoLS is also expected to register employment contracts, regularly monitor PEA, and communicate with the labour attachés in destination countries to ensure the protection of migrant workers.

A licensed PEA, owned by an Ethiopian national and with a capital of 1 million ETB (€18,519), are held accountable for the welfare of employees and necessitate bond requirements for license. In addition to the license requirements, the overseas agencies are expected to have a representative consular office in the destination country. This office is expected to have sufficient facilities that provide temporary food and shelter to migrants upon their arrival. In Ethiopia, the PEAs are also expected to have an office where they can provide pre-employment and pre-recruitment orientations as instructed by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. The PEAs are responsible for follow-up on contracts, capacity of overseas employees to pay wages, and safety of migrants.

PEAs also provide short term pre-employment orientation and counselling services. MoLS is also similarly tasked with providing regular pre-employment and pre-departure awareness raising to citizens who show interest to take-up overseas employment pertaining to the conditions of receiving countries. A pre-departure training manual has been developed by the ministry in 2016 together with EU, ILO and UN Women (ILO 2016). TVET (Technical Vocational Education and Training) agencies provide occupational training to migrants and provide certificates of occupational competence in line with the occupational standards for labour migration developed by MoLS.

In 2021, the Ethiopian Overseas Employment Proclamation (No. 923/2016) was amended to Ethiopia’s Overseas Employment Proclamation Amendment (No. 1246/2021).[6] The amendments include the exclusion of the requirement for 8th grade education for any worker who desires to take-up overseas employment. Under the revised proclamation, workers are only required to provide certificate of occupational competence.

Prevention and suppression of trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants proclamation

To regulate the growing scale of irregular migration out of the country and provide protection to migrants, the Ethiopian government also introduced different legal documents and regulations. The Prevention and Suppression of Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants Proclamation No. 909/2015[7] was developed in response to the abuses experienced by low-skilled migrant workers in the Middle East, most of whom were female domestic workers. The proclamation clearly defined human trafficking and smuggling and the penal codes for such crime, it fines individuals up to 500,000ETB and 15 years to life imprisonment if caught in the process of human trafficking. The Proclamation recognises the Government’s anti-trafficking law enforcement efforts, which focus on transnational labour trafficking. The Anti-Trafficking Proclamation also addresses the return and repatriation of victims of trafficking, including assistance and protection upon their return. Following, in 2018, the National Reintegration Directive[8] (No 65/2018) was drafted to provide a framework for return and reintegration programmes (FDRE 2020).

In collaboration with IOM, the National Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons was also drafted in 2015.[9] This five-year plan aims at reducing, managing and controlling human trafficking. Six priorities were identified within this plan:

- Prevention and awareness raising with respect to the risks of illegal migration;

- Development of government procedures to address trafficking;

- Provision of direct support for Ethiopian victims of trafficking who are repatriated, and non-citizen survivors of trafficking in Ethiopia;

- Improvement of legal measures that help to prosecute traffickers and provide victim assistance;

- Capacity building for government officials;

- Trafficking related data management

Directives have also been developed to regulate rehabilitation management and national referral mechanisms for victims of trafficking. Under these initiatives, the Ethiopian government identified six thematic areas:

- Awareness and promotion of overseas employment;

- Law enforcement;

- Protection of returnees and vulnerable migrants;

- Diaspora engagement and development;

- Migration data management;

- Migration research

National migration policy

Following the Global Compact for Migration (GCM), signed in 2018, the Ethiopian government initiated the development of a National Migration Policy, which is currently underway (FDRE 2020). The upcoming migration policy is aligned with the country’s national development plan and is focused on creating jobs for nationals through industrialization and enterprise development. A technical working group has been formed, comprising of different stakeholders, to prepare a comprehensive migration policy. To assist with this, migration governance indicator (MGI) was developed by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Attorney General Office and IOM (FDRE 2020). In April 2022, the draft policy was presented to stakeholders (development partners, embassies, and UN agencies) and to be presented to the Council of Ministers.[10]

An Ethiopian Migrants Data Management System has been set up under the Ministry of Labor and Skills to support services with a database of Ethiopian migrants working abroad. By providing reliable statistics on the trend and magnitude of migration from Ethiopia, the data set is aimed to shape the policy landscape that has for long been designed by the political interests of the government and other external factors (FDRE 2020).

2.2. Refugee and Asylum

Ethiopia has a long-standing history of hosting refugees and is currently the third-largest refugee hosting country in Africa. As of February 2022, there are over 837,533 refugees in Ethiopia from around 26 countries including Angola, Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Liberia, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, Syria, and Yemen (UNHCR 2022). Most of the refugees are South Sudanese (390,612), Somalis (228,797), Eritreans (158,662), Sudanese (46,789) and Yemeni (2,490) (UNHCR 2022), among which men account for the majority at 70.9% of all migrants. Most refugees live in 24 refugee camps, located across five regional states bordering neighbouring countries (Carver 2020; Carver, Gebresenbet, and Naish 2018).

Insecurity, political instability, military conscription, conflict, conflict-induced famine, drought and other problems in the East African region are factors among which an increasing number of refugees and asylum seekers come to Ethiopia (Carver 2020). The country has an open-door policy for refugees, which includes protection for asylum seekers. This open-door policy, along with the country’s relative stability amidst rising conflict and instability in the horn of Africa, has led to a surge in the number of refugees, mainly from Eritrea and Somalia, over the past decade, from under 100,000 in 2008 to almost a million in 2018.[11]

However, political unrest and conflict in different parts of the country since 2018 has affected the life of refugees that seek protection in Ethiopia. As of July 2020, the total number of registered refugees and asylum seekers was estimated to be 769,310, showing a decline from 2018 (909,301) (UNHCR 2018; 2020). Further, the war in the northern part of the country since November 2020 has resulted in the destruction of refugee camps in Tigray region that led to the displacement of significant number of Eritrean refugees and interruption of humanitarian assistance. In response, the Ethiopian government, in coordination with UNHCR, attempted to relocate refugees residing in the war zone to a newly established camp in North Gondar Zone.[12]

In addition to camps, the country also hosts a significant number of urban refugees. In 2021, UNHCR reported 71,187 registered urban refugees in Addis Ababa, mostly Eritreans, Somali and Yemeni refugees. Irrespective of the encampment policy, the Ethiopian Refugee Proclamation states ‘authorised exceptions’ under which refugees can reside in urban areas. These exceptions include access to medical treatment and other health reasons, safety concerns, and access to higher education. Under such circumstances, refugees are allowed to live in urban areas with monthly allowance and medical assistance. These are assisted urban refugees registered under ARRA (Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs), a government body concerned with administering refugees and refugee camps (NRC 2014).

Another legal arrangement for urban refugees is the Out-of-Camp (OCP) permit, although this is only applicable to Eritrean refugees. This scheme, implemented since 2010, allows Eritrean refugees to settle in urban areas under the authorisation of ARRA. Unlike assisted refugees, OCP holders are not eligible for any economic assistance and support from ARRA or other concerning bodies. The primary condition for requesting an OCP is proof of self-sufficiency, the assumption being OCP holders are able to support themselves through a sponsor. Another criterion demanded from the refugees is to stay in refugee camps from three to six months. Once granted an OCP, their mobility is restricted to the registered urban area unless provided with a “specific authorisation” from ARRA. This, however, takes time and is allowed for a limited number of days. The majority of Eritrean refugees living in Addis Ababa are registered within the OCP scheme (NRC 2014).

Non-permit holders and unregistered asylum seekers are also among refugees living in Addis Ababa. These include refugees who moved out of the camps without authorization from ARRA and refugees who come into Ethiopia without any documentation and recognition from the Ethiopian government (NRC 2014).

For registered urban refugees, the urban refugee reception centre in Addis Ababa provides registration, documentation, individual protection, and resettlement counselling to urban refugees. Different organisations also offer direct assistance and cash-based interventions (CBI) to urban refugees (NRC 2015).

2.2.1. Policies and Regulations

Ethiopia is a signatory to the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the 1967 Protocol and the 1969 OAU Convention Governing Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. Based on these instruments, Ethiopia adopted the 2004 National Refugee Proclamation. Refugee Proclamation No.409/2004[13] prohibits the government from refusing entry to refugees or asylum seekers and returning them to any country where they would be at risk of persecution. It grants refugees some rights, but still has some restrictions on the rights of movement, wage employment, and access to education. The proclamation demands that refugees live within camps, restricting their mobility.

In 2016, as a reaction to the global displacement crisis, the international community formulated a holistic, global, more equitable and predictable refugee response. During the Leaders’ Summit, UN member states including Ethiopia, signed the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, reminding the international community of its global responsibility to protect the rights of migrants and refugees. This declaration includes the Comprehensive Refuge Response Framework (CRRF), which lists concrete actions on how to ensure these rights. It argues for a holistic approach, linking humanitarian aid with development, to ensure access of refugees and host-communities to public services, including education and employment. The framework was piloted in February 2017 and nationally launched in November of the same year (RRP 2020).

In September 2016, Ethiopia co-hosted the Leader’s Summit in New York, which was held the day after the adoption of the New York Declaration on Refugees and Migrants. At the summit, the Government of Ethiopia made the following nine pledges to relax its reservations to the rights of refugees to free movement and work, and to strengthen support to refugees (RRP 2020).

Box One: Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework Nine Pledges (RRP 2020)

CRRF Nine Pledges

- To expand the Out of Camp policy to apply to all nationalities (currently applicable only to Eritreans), and to 75,000 refugees, or ten percent of the current refugee population in Ethiopia, to be expanded as resources allow

- Provide work permits to refugees and those with permanent residence ID within the bounds of domestic law

- Issue birth certificates to refugee children born in Ethiopia

- Increase the enrolment of refugee children in school, from 148,361 students to 212,800 students overall

- To make available 10,000 hectares of irrigable land to allow 20,000 refugee and host community households (100,000 people) to engage in crop production by facilitating irrigation schemes

- To allow for local integration for protracted refugees who have lived in Ethiopia for 20 years of more, to benefit at least 13,000 refugees in camps identified by ARRA

- To work with international partners to potentially build industrial parks that could employ up to 100,000 individuals, with 30% of the jobs to be reserved for refugees

- To strengthen, enhance, and expand basic social services for refugees, including health, immunisation, reproductive health, HIV, and other medical services

- To allow refugees to obtain bank accounts, driver’s licenses, and other benefits to which foreigners are entitled

The pledges made by Ethiopia are in line with the objectives pursued by the international community through the CRRF. In Ethiopia, therefore, the CRRF will be best applied through the implementation of these commitments, with the CRRF serving as a vehicle to implement the pledges. The pledges are also aligned with the government of Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II).

The refugee proclamation was revised in 2019. Proclamation No. 1110/2019[14] clearly defines the rights of refugees in terms of residency in Ethiopia, access to education, health services and financial services, the right to engage in wage-earning employment as individuals or in groups in agriculture, industry, micro and small-scale enterprises, handcrafts, and commerce.

The new proclamation allows refugees the right to engage in gainful employment, a major improvement compared to the previous proclamation. Under the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants (no 84), states are encouraged to make the labour market accessible and open to refugees. The commitment, which was signed by Ethiopia, entails creating employment and income generation schemes. Opening up the work environment and extending opportunities to refugees includes lifting legal barriers and making training and labour-market information accessible. Hence, refugees can secure lawful work without discrimination on the basis of their refugee status, access labour protection that safeguards them from exploitation or wage theft and earn a fair wage.

Other critical improvements that are pertinent to the social and economic development of refugees are: the right to associate, including the right to be members or to form cooperatives; the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose their residence; the right to acquire movable or immovable property, access to leases and other contracts relating to the property; the right to open a personal bank account, deposit, transfer or withdraw money and obtain other banking services in accordance with relevant Ethiopian financial laws using identification document issued by Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA). These rights are fundamental for the refugees, either as individuals or in groups (cooperatives or self-help organisations), to engage in business activities, to access financial services as well as business development services. Carver (2020), however, criticizes the proclamation for limiting these rights through structural and bureaucratic procedures.

Further, ARRA developed a Country Refugee Response Plan (RRP) (2020–2021), based on the Global Compact on Refugees, to facilitate the implementation of the nine pledges Ethiopia committed to in the CRRF. The plan aims to improve services provided to refugees through a clear list of objectives, performance targets, and implementing/supporting stakeholders. Refugee responses are developed for the different refugee population groups in Ethiopia under the following strategic objectives.

Box two: Strategic objectives guiding Ethiopia’s refugee management (RRP 2020)

Strategic Objective (2): Strengthening refugee protection through the expansion of improved community-based and multi-sectorial child protection and SGBV programmes inclusive of PSEA and MHPSS;

Strategic Objective (3): Strengthening access to inter alia education, WASH, health including sexual and reproductive health, and nutrition, livelihoods, energy, and sanitary items;

Strategic Objective (4): Supporting the implementation of the Government’s CRRF Pledges and GRF commitments to expand access to rights, services and self-reliance opportunities in the longer-term, in line with the Global Compact on Refugees;

Strategic Objective (5): Contributing to the development of a stronger linkage with national/regional development related interventions, and,

Strategic Objective (6): Expanding access to solutions including resettlement opportunities, voluntary repatriation when feasible, legal migration pathways as well as local integration.

The RRP further aims to provide refugees with self-reliance and socio-economic integration, and integration of refugees into the economy and national development plan is one of the main focus areas of the plan. As part of this, an attempt was made to link the CRRF with Growth and Transformation Plan II (GTPII), the country’s development roadmap (2015-2020). The nine Pledges were made to align with Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II), the country’s development roadmap (2015-2020). Phasing out of the encampment-based approach is also another goal of the strategy. It also emphasises inclusion and the peaceful co-existence of refugees with host communities. It seeks a “durable solution” that grants refugees self-reliance and socio-economic integration.

Overall, in the effort to provide a comprehensive approach to refugees in the country, the abovementioned legal frameworks have been adopted. While not an exhaustive list, it includes the most relevant legal frameworks applicable for refugees living both in and out of the camp setting.

Table 1: Summary of Legal Frameworks on Refugees

|

Legal Document |

Year |

Key Focus |

|

National Refugee Proclamation, No. 409/2004 |

2004 |

This was the first policy and main legal framework that guided the protection of refugees in the country until 2019. |

|

Government of Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II), 2015/16-2019/20 |

2015 |

The Pledges made by the government during the Refugee summit are also aligned with the GTP II that serves as the main national development framework. |

|

Integrated Refugee Response plan for Ethiopia |

2015 |

The plan outlines the collective response of fifty-four humanitarian and development agencies over the next two years in support of all registered refugee population groups in the country. The Plan aims to ensure the increased coherence and alignment of all planned interventions supporting refugees against a common set of sectorial objectives and performance targets, to improve coordination and further timely and effective protection and durable solutions, including through the strengthening of community-based and multi-sectorial child protection and SGBV programmes.

|

|

The Ethiopian Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework |

2017 |

The CRRF can be regarded as the process for implementing the Government’s nine pledges, with the Government aiming to pursue a more sustainable response that goes beyond providing humanitarian assistance to refugees towards promoting their self-reliance. |

|

Refugees Proclamation n°1110-2019 |

2019 |

In accordance to its engagement under the Global Compact on Refugees, the proclamation extends the provision of the existing 2004 Proclamation related to protection and assistance to refugee into a more comprehensive framework in which refugees access primary education, obtain driving licenses, as well as legally register life events such as births and marriages and open up access to national financial services, such as banking. |

|

2019-2020 Ethiopia Country Refugee Response Plan (ECRRP): |

2019 |

Collective response of fifty-four humanitarian and development agencies over the next two years in support of all registered refugee population groups in the country. The Plan aims to improve coordination and effective protection and durable solutions, including through the strengthening of community-based and multi-sectorial child protection and SGBV programmes. |

2.3. The Diaspora

The Ethiopian diaspora[15] is estimated to be over two million, mainly in North America, the Middle East, and Europe (ILO 2020). The top destination countries for the Ethiopian diaspora include the United States (239,186), Saudi Arabia (160,192), Israel (78,258), Sudan (62,565) and Canada (34,921) (AFFORD 2020). The actual number of Ethiopian nationals living abroad might be higher because of the unregulated outward migration, that is most often ‘irregular’. Ethiopia has been creating different opportunities for the diaspora, mostly related to its engagement in investment and development projects. the Investment Proclamation No 280/2002[16] was the first legal instrument that directly addressed the diaspora community. The proclamation aimed to make investment in Ethiopia attractive to the diaspora by including foreign nationals of Ethiopian descent as part of domestic investors, which allows them to own ‘immovable’ assets such as land in Ethiopia.

Remittances account for more than 5% of Ethiopia’s GDP and one quarter of the country’s foreign exchange earnings; the remittance flow in the year 2020 was recorded to be 411 million USD (AFFORD 2020). However, the majority of the remittance flow is through informal mechanisms, which will put the recorded remittance flow by the government to a much higher number. To encourage and regulate the remittance flow, the National Bank of Ethiopia Directive No. FXD/30/2009 was enacted and focused on foreign currency bank accounts directed at the diaspora with an objective of encouraging investment from the diaspora and supporting the international foreign exchange reserve of the country. It further aims to enhance access to efficient remittance service providers by avoiding commission for local banks that pay out of remittances. The second Growth and Transformation Plan also mentions the contribution of the diaspora in the country’s development through direct investment in health and education sectors, especially in regional states. Further, Investment Proclamation No. 769/2012[17] provides the diaspora with tax incentives, such as corporate income tax exemption for up to 10 years and personal income tax exemption for expatriate employees of industrial park enterprises for five years. The areas of investment involved are however limited and there are investment sectors allowed for the government only such as electricity provision, postal service, air transport (until recently).

The 2013 diaspora policy[18], which was revised in 2015[19], also focuses on engagement of the diaspora in development, participation in the country’s democracy process and peace building, and advocacy. The policy further emphasises on the importance of knowledge transfer and introduction of technology in different sectors mainly agriculture, education, health, manufacturing and service sectors. Though the diaspora has limited rights in political participation such as voting, they entertain equal rights with locals in accessing resources and services; Proclamation No. 270/2002[20] provides for the issuance of a special identification card, the Yellow Card, for the diaspora to get such services. The Yellow Card (Ethiopian Origin ID Card), for foreign nationals of Ethiopian origin, is issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to provide them with rights and privileges applying to Ethiopian nationals with an exception of the right to vote or be elected and employment in certain sectors such as security.

The Ethiopian government has recently introduced different initiatives to tap into the opportunities the diaspora community can offer. The Ethiopian Diaspora Trust Fund (EDTF) was created in 2018 to involve the diaspora in socio-economic projects in Ethiopia by financing social and economic development projects. The country also launched diaspora bonds to support the construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile in 2008 and 2011 (AFFORD 2020). The Connecting Diaspora for Development (CD4D) initiative was also launched in 2016 to promote short term return of the diaspora to support skill transfer and diaspora enterprise.[21] This initiative was supported by the Dutch government and focused on engaging a highly skilled diaspora in entrepreneurship. Other initiatives were also introduced recently following the conflict in the northern parts of the country and the government’s request for the diaspora to be active in advocacy and involved in political discussions.

2.4. Migration Governance Structure

The migration governance structure in Ethiopia differs according to the type of migration as identified in the above sub-sections. There is no unitary structure that deals with mobility from and to the country, though there are overlapping responsibilities given to the different government organs that are concerned with migrants, refugees and the diaspora.

For Ethiopian migrants, the Ministry of Labor and Skills (MoLS), the former Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, take the lead in governing, regulating and managing migration from Ethiopia. The ministry is tasked with facilitating ‘regular’ labour migration from and to Ethiopia. The ministry provides the necessary skills and trainings to potential Ethiopian migrants who have access to overseas employment. It also regulates employment opportunities made available to foreigners in the country. Above all, the MoLS aims to provide job opportunities to Ethiopians as a solution to the drivers of international migration from Ethiopia, which is mainly economic. IOM (International Organisation for Migration) works together with MoLS in creating awareness on ‘irregular migration’, providing training to different stakeholders on human smuggling and trafficking, and repatriation of Ethiopian migrants from host countries. IOM also works with host communities and other stakeholders to address the needs of Ethiopian migrants and internally displaced peoples (IDPs), focusing on interventions that target migration governance, emergency and post-crisis situations.

The Anti-Human Trafficking and Smuggling of Migrants Task Force and National Anti-Trafficking Council, established in 2011 and 2012 respectively, govern the activities that are implemented by the government to stop human trafficking and smuggling. The taskforce brought together different stakeholders, including government and non-government organisations, international/humanitarian organisations, and faith-based organisations, to tackle human trafficking and smuggling from Ethiopia. The taskforce had four technical working groups: protection, which was led by the Food Security and Urban Job Creation Agency; prevention under the responsibility of MoLS; prosecution led by the General Attorney’s Office; and research led by the Ministry of Education. Across the working groups, the taskforce was chaired by the General Attorney Office and was accountable to the National Anti-Trafficking Council. The council, headed by the Deputy Prime Minister, oversees the National Anti-Trafficking Task Force and also evaluates, assists and directs taskforces and various working groups based on their performance. The Anti-Trafficking Council is composed of concerned ministries, presidents of regional governments, mass associations, religious leaders and renowned personalities. The taskforce and council were further replicated at regional and zonal level to coordinate day-to-day activities. However, the taskforce has ceased to exist recently. At present, the functional structure that deals with international migration of Ethiopians is the MoLS and Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) is also responsible for the Ethiopian diaspora. The Diaspora Engagement Affairs Directorate deals with the involvement of the diaspora community in and outside Ethiopia. The Ethiopia Diaspora Agency was later established in 2018, under MoFA, to facilitate Ethiopians and foreign nationals of Ethiopian origin engage in the development endeavours of the country (AFFORD 2020).

The former ARRA (Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs), under the Ministry of Peace, is the government agency responsible for overseeing activities related to refugees. Accountable to the Prime Minister, the agency was given the responsibility to:

- Serve as a key government agency and representative on all matters of refugees and asylum-seekers;

- Conduct refugee status determination exercises and decide on refugee status;

- Establish refugee camps and manage the overall coordination of camp activities;

- Provide physical protection and maintain the well-being of all people of concern;

- Provide and coordinate basic and social service delivery to refugees;

- Coordinate country-level refugee assistance programs;

- Assist and facilitate NGO partners and other stakeholder interventions in the discharge of their activities; and

- Facilitate and undertake repatriation movements when the causes of refugee displacement are solved.[22]

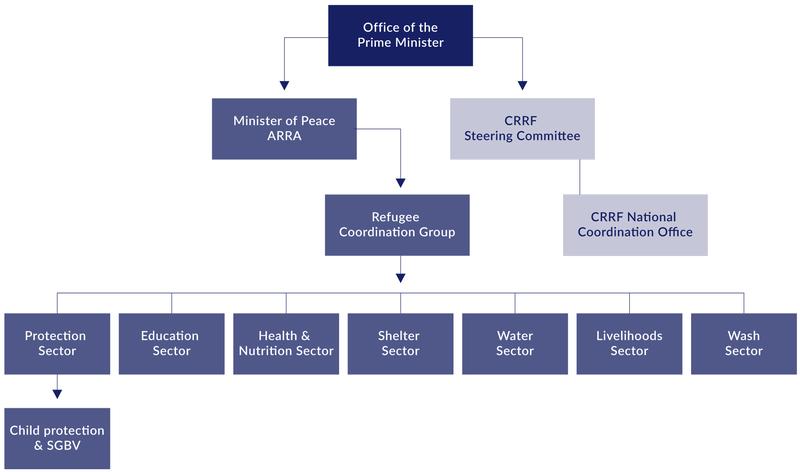

ARRA is the leading agency in the protection and assistance of refugees and overall coordination of refugee interventions in Ethiopia. Meanwhile, UNHCR takes the lead in managing refugee camps across the country. In addition to UNHCR and ARRA, the country’s refugee response plan identifies stakeholders (humanitarian and development partners as well as government offices) that can coordinate in implementing the CRRF and the national strategy (RRP 2020). In addition to UNHCR, the ILO (International Labour Organisation) has also been supporting work on refugees, particularly in relation to livelihood opportunities, access to the labour market, rights to work, rights at work, and access to education and training.

Figure 2: Organisational structure for refugee intervention

There are also different coordination mechanisms to increase the synergy between the different organisations, such as the Ethiopian CRRF National Coordination Office, the Ethiopian CRRF Steering Committee, The Refugee Coordination Group, The Humanitarian Response Donor Working Group and A Multi-Stakeholder Nexus Group.

In 2022, however, the former ARRA was restructured into RRS (Refugee and Returnee Services) to integrate services provided by the government both to refugees and Ethiopian migrants (returnees), including IDPs (internally displaced peoples). This restructuring enabled the government to bring together the previously separated institutions that govern international migrants, IDPs and refugees. However, the newly established RRS is only limited to Ethiopian returnees, while labour migration from Ethiopia is still governed by the MoLS.

3. Regional Context: IGAD States

At the regional level, there have been different frameworks developed to regulate migration, promote coordination and strengthen structures. The migration policy framework for Africa (MPFA) (2018-2030)[23] is one such framework. It was adopted by the AU in 2018 with an objective of facilitating safe, orderly and dignified migration focusing on eight interventional areas:

- migration governance;

- labour migration and education;

- diaspora engagement;

- border governance;

- irregular migration;

- forced displacement;

- internal migration; and

- migration and trade.

The MPFA was adopted as a comprehensive policy approach by Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)[24] to promote migration management in the region and support States. While no member state has drafted a national migration policy, the framework is aimed to provide guidance on countries’ policy and legislation. The approach taken in this framework is promoting well managed migration for the development potential of both countries of origin and destination. It also emphasises the protection of migrants, including IDPs and refugees.

Following this, the AU launched the Joint Labour Migration Program (JLMP) that promotes free movement of labour migrants to encourage regional integration and development.[25]

also aims to make migration voluntary and legal and combat human trafficking and smuggling by implementing the EU–Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative (Khartoum Process). The partnership, implemented in five African countries, namely Ethiopia, Nigeria, Niger, Mali and Senegal, establish cooperation between EU and the selected countries for “sustainably managing migration flows” by engaging in humanitarian assistance, return of migrants to countries of origin and transit, and address the root causes of irregular migration and forced displacement in countries of origin (Castillejo 2017). The Migration Action Plan (MAP) (2015-2020)[26] was drafted in 2014 to operationalize the MPF through 12 strategic priorities, addressing regional concerns, which include the following:

Figure 3: The Migration Action Plan 12 Strategic Points (MAP 2015)

- Migration Governance Architecture

- Comprehensive National Migration Policy

- Labour Migration

- Border Management

- Irregular Migration

- Forced Displacement

- Internal Migration

- Migration Data

- Migration & Development

- Inter-state & Inter-Regional Cooperation

- Migration, Peace & Security

- Migration & Environment

Further, dialogues on migration management and regional cooperation among member states have been underway through the Regional Consultative Process on Migration (RCPM). The objective of the process is also to attain policy coherence in migration and strengthen capacity of countries and the region at large in implementing the MPF and other regional policies.[27] The RCPM has the overall objectives of:

- facilitating dialogue and regional cooperation in migration management amongst IGAD member states by fostering greater understanding and policy coherence in migration, and

- strengthening regional, institutional and technical capacities to implement the migration policy framework for Africa and other AU/IGAD policies on migration.

The RCPM, in the IGAD region, with a total of 11 consultations until 2018, facilitated dialogues to bring member states together and have a common understanding of the migration trend and dynamics in the region and created platforms for member states to establish networks.

The National Coordination Mechanisms on Migration (NCM), government led coordination platform, has been established in member states, the most active being in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan. In Kenya, the NCM established and strengthened the national platform to coordinate mechanism on migration, and “steered debate and dialogue on migration related issues in order to realize coherence and inclusive attainment of the country’s migration priorities”.[28] Further, a regional technical working group has been established to facilitate capacity building, the accessibility of migration data, share and build on existing good practices.

In general, IGAD’s engagement is focused on migration governance, policy framework and regular migration and durable solutions for refugees. The RCPM and NCM are, for instance, aimed at establishing a migration governance architecture in the region and bringing policy dialogue. Most of the focus has also been on cross-border movement and border management. The agreement reached between Ethiopia and Kenya and Ethiopia and Sudan on cross-border trade and mobility is taken as one of the achievements of the regional organisation.

Another accomplishment of IGAD has been the protection of refugees hosted by member states. The Djibouti Declaration on Refugee Education (2017)[29] ensured member states to formulate national plans to integrate refugees in their education system. The 2019 the Kampala Declaration on Jobs, Livelihoods and Self-Reliance,[30] adopted by IGAD member states, also emphasized on the right to work and right at work of refugees in host countries.

IGAD also engages with the EU, mainly through the Better Migration Management (BMM) programs. However, the discussion between EU and IGAD mainly focus on ‘security concerns’ that are resulted from migration and restricting movement outside the continent. Lavenex et.al. (2015) argue the EU has “strongly influenced how the migration question has been addressed" and with the lack of incentive and sufficient resources from member states to manage migration, claim that the EU established the framework for regional migration governance and financed related initiatives in collaboration with IOM (Lavenex et.al. 2015). Another report indicated that IGAD has been a priority for EU in terms of migration because of the significant number of migrants that originate from the area. The EU has provided financial, technical and political support to IGAD to manage migration and forced displacement in the region (EUTF 2021).

IGAD-EU relations have been highly impacted by AU-EU relations that adopted different documents including the 2006 Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development (Rabat Process) and the Joint Africa–EU Declaration on Migration[31] that emphasized better manage migration and development, organizing mobility and legal migration, improving border management, and combating irregular migration. In 2007, the Joint Africa–EU Partnership on Migration, Mobility and Employment (Tripoli Process),[32] which focuses on creating more and better jobs in Africa was drafted. The EU–Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative (Khartoum Process)[33] later came into action in 2014 and the Action Plan of the Valletta Summit on Migration in 2015. These focus on combating human trafficking and smuggling and addressing the root cause of migration from the continent.

4. EU-Ethiopia migration policy relations

The European Union and its member states have taken different approaches to dealing with the issue of migration from and through Ethiopia, mainly related to refugees from Ethiopia and the region. Ethiopia has been the focus of the EU because of its importance in the migration flow in the Horn of Africa as a country of origin and transition.

The EU Emergency Trust Fund (EUTF) is at the forefront of EU-Ethiopia relations with respect to migration. The EUTF came into being at the Valletta Summit in 2015 where European and African countries came together to come up with a common approach to address migration. The EUTF aims to address the root cause of ‘irregular’ migration and displacement by mainly working on migration policies, governance and partnership for development. Another objective of the EUTF has been to reinforce the protection of migrants and asylum seekers, prevent and fight migration smuggling and human trafficking, and enhance cooperation on legal migration and mobility. The EUTF also focuses on development projects focusing on livelihood opportunities and resilience building. Its focus, however, has been mainly to stop ‘irregular’ migration to Europe and facilitate the migration dialogue between the two continents (Tardis 2018). The EUTF was born out of the anti-migration sentiment and a political shift that has been rising in European countries, which is implied in the overall focus of the program on the lessening of the migration flow to Europe. The humanitarian aid and development approach within the EUTF has also been coupled with the crisis approach, which has guided EU’s foreign relations on issues related to migration (OXFAM 2020).

The EUTF and the Migration Partnership Framework (MPF) strengthened EU engagement with on migration from Africa and revisited the pre-existing EU’s foreign policy on migration, making agreements with African countries to reduce migration of African nationals to European states. Importantly, the EUTF and MPF also impacted the policy landscape in the African continent, including Ethiopia (European Union 2020).

Ethiopia has been identified as one of the five countries in the and has been one of the main countries to receive funds under the EU Emergency Trust Fund (EUTF) and the country has received around 270 million euros (OXFAM 2020). Ethiopia also signed the Common Agenda on Migration and Mobility (CAMM) with the EU in 2015. Since 2016, the CRRF is also being piloted in Ethiopia and Ethiopia has been the chair of the Khartoum Process that aims to enhance regional cooperation on migration and mobility between the Horn of Africa and the EU.

Ethiopia, from the Horn of Africa, also receives the largest humanitarian aid from the EU. The aid has provided funding to projects that focus on providing services to refugees hosted by Ethiopia and the host communities. As part of the Khartoum process, the EUTF, working with the German Association for International Cooperation (GIZ), implemented the BMM (Better Migration Management) program that focused on improving migration management, particularly in relation to human trafficking and smuggling.

In the context of the BMM, migration management is concerned with a range of activities which aim to improve the quality of migration to ensure people’s rights are respected as they move, their movement is facilitated by more efficient and effective border regimes and there is an appropriate framework of law that enables regular and reduces irregular movement. BMM’s activities are focused around four priorities: supporting the development of coherent national migration policies; building capacity to implement these policies, in particular improving the quality of law enforcement through the training of front-line actors; enhancing the protection of migrants who are vulnerable to abuse, in particular those who are subject to trafficking; and awareness-raising on the dangers of irregular migration and benefits of alternative options.[34]

Another project under the EUTF is the programme Stemming Irregular Migration in Northern and Central Ethiopia (SINCE) that aims to reduce irregular migration in Ethiopia by improving the living conditions of the most vulnerable population, mainly women, and provide job opportunities within the country. Implemented by the Italian cooperation agency, SINCE focuses on improving the resilience of the community and promoting local development.[35] Resilience Building in Ethiopia (RESET II) is another project implemented in the EUTF to improve food security, access to basic services and enhanced livelihoods in conflict-prone areas in Ethiopia.[36] The Regional Development and Protection Programme in Ethiopia (RDPP) also aims at improving the living conditions and addressing the long-term development and protection needs of refugees and their host communities.[37]

As a result of these projects, and many others that focus on supporting the Ethiopian government response to migration, the country has adopted a revised refugee proclamation that provides refugees with the right to work, access to education and freedom of movement. The national migration policy that has been drafted is also aimed to provide a comprehensive framework for the migration flow to and from the country. A reintegration directive has been implemented to facilitate and coordinate the reintegration process of migrants.

Most of these projects and legal frameworks influenced by the EUTF however put most stress on stopping irregular migration and improving the provision of protection. The development cooperation between the EU and Ethiopia seems to have less attention and was designed without consultation with concerned stakeholders. The Ethiopian government has criticized the EU for failing to provide more support on job creation and addressing the issue of legal migration (CONCORD 2018). Implementing partners are also reserved to international NGOs and European agencies, which has caused concerns. Lack of focus of the programs on structural and policy change, issues of sustainability and scalability are also among the criticisms forwarded by the Ethiopian government on the EUTF programmes (Castillejo 2017).

There is also the argument that development aid by the EU has been used to put pressure on African countries to facilitate the return of migrants. A report by OXFAM (2020) argues that there has been an agreement between the EU and Ethiopian government since 2017 which assures the voluntary and forced return of Ethiopian nationals to their country. However, there was no official documentation of this agreement. There were also concerns of political migrants forced to go back to their country and facing prosecution. According to the Oxfam report, 400 migrants returned in 2018 with a 15.5-million-euro budget allocated under the EUTF. This has, however, caused challenges in strengthening the partnership between the EU and Ethiopia. While repatriation and return of migrants is not a priority for Ethiopia[38], the EU emphasises the need to work more on this.

The cooperation with the EU has also ignored harnessing the opportunities for regular migration as agreed on the global compact for migration. Further, according to Mehari (2020), “the power asymmetry (financial and diplomatic) between Europe and Africa has distorted the priorities of Africa and created pressure to implement policies that give precedence to Europe’s interests over those of African countries and migrants”.

5. Conclusive remarks

From the above, it can be discerned the relation between Ethiopia, IGAD and the EU is based on the best and aligned interest of the respective actors. For the Ethiopian government, that has focused on the importance of remittance in its diaspora policy within the limited livelihood opportunities the country’s resource can provide, migration from Ethiopia is seen as an opportunity, if ‘well managed’ and ‘regular’. IGAD also promotes ‘migration management’, emphasizing protection and development. The regional organisation also involves activities and discussions that encourage free cross border mobility in the region to facilitate cooperation between the different States. Meanwhile, the EU is focused on ‘managing’ migration from the region, with a priority given to addressing push factors in Ethiopia. Accordingly, the term ‘management’ of migration has been integrated in the policies and programmes of the EU, IGAD and Ethiopia, however from different perspectives. Regardless, programs such as the EUTF that focus on migration management have been implemented by these different stakeholders, shifting the narratives and intervention areas on migration.

Following the interest of donor organisations and a push from European countries that host refugees from the Horn of Africa transiting through Ethiopia, the Ethiopian government has been strongly invested in accommodating refugees, as can be seen in the presence of high engagement in the legal frameworks and programs that focus on refugees. Regardless of the concern from its citizens on the availability of opportunities for Ethiopians, the government has opened up the labour market to refugees, following the implementation of the CRRF pledge. The new consolidation of the Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) into the Refugee and Returnee Services (RRS) is also partly focused on returning and reintegrating Ethiopian migrants from EU countries. The RRS indicate this the organisation is “committed to expand its partnership to ensure comprehensive and holistic reintegration support; […] and closely working with the EU to provide sustainable reintegration support to Ethiopian returnees from the EU member states plus Norway and Switzerland and other parts of the globe”.[39]

The policies and structures put in place to implement different programs related to refugees are also focused on intervention areas that are guided by the frameworks at regional and international level. As such, more emphasis has been on livelihood, health, education, and protection. The revised refugee proclamation and the different directives attest to this, providing access to refugees on these areas. Ethiopia has been adamant to open up the labour market to refugees because of the limited resources in the country. However, following the EUTF and the CRRF pledge, the revision in the proclamation added clauses that give access to free movement and involvement in the labour market to refugees.

The legal frameworks on labour migration have also been focusing on international ‘irregular’ migration of Ethiopians. Emphasis has been on protection from smuggling and trafficking and providing better job opportunities in the country, which is similar to the focus of the EUTF. However, less has been done on promoting ‘regular’ migration and harnessing the opportunities the country can get from international migration of its citizens.

References

AFFORD. 2020. Diaspora Engagement Mapping: ETHIOPIA

AMDPC. 2021. Host Governments and Communities Engagement with and Responses to Forced Displacement in East Africa: Scoping a Research Agenda for Kenya and Ethiopia. Nairobi.

Asnake K. and Fana G. 2021. Youth on the Move: Views from Below on Ethiopian International Migration. London: Hurst and Company

Asnake K. and Zerihun M. 2015.Ethiopian Labor Migration to the Gulf and South Africa.Forum for Social Studies (FSS), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Carver, F. 2000. Refugee and Host Communities in Ethiopia. ODI and DRC, UK.

Carver, F., Gebresenbet, F. and Naish, D., (2018). Gambella Regional Report: Refugee and Host Community Context Analysis. ODI and DRC, UK.

Castillejo, C. 2017. The EU Migration Partnership Framework Time for a rethink? Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik

CONCORD. 2018. Partnership or Conditionality: Monitoring the Migration Compacts and EU Trust Fund for Africa.

Eldin, A. and Ferede, T. 2018. Assessment of Seasonal Migration Management System on the Sudan-Ethiopia Border

European Union. 2020. EU External Migration Policy and the Protection of Human Rights. European Parliament

EUTF. 2021. IGAD Case Study: Focus on IGAD’s Work on Migration in the Horn of Africa.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). 2020. National Voluntary Report on the Implementation of the Global Compact on Migration For the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. National Partnership Coalition (NPC) on Migration

Gesellschaft für Internationalle Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). 2018. Better migration management: Horn of Africa.

Guday E. and Kiya G. 2013. ‘The Conception of Gender in Migration to the Middle East: An Anthropological Study of Gendered Patterns of Migration in North Wollo Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia’. In: EJDR, Vol 35(1): PP 107-146.

Horwood, C. 2015. Irregular Migration Flows in the Horn of Africa: Challenges and implications for source, transit and destination countries. Occasional Paper Series, No. 18|2015. Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

ILO. 2016. Rights and Responsibilities of Relevant Actors on Labor Migration in Ethiopia.

Jones, N., Presler-Marshall, E., Bekele T., Guday E., Bethelihem G., and Kiya G. 2014. Rethinking Girls on the Move: The Intersection of Poverty, Exploitation and Violence Experienced by Ethiopian Adolescents involved in the Middle East “Maid Trade”. ODI

Kiya G. 2021. Contextual Borders: A Moving Zone of Religion along the Ethiopia-Sudan Border of Metema Yohannes. PhD Thesis

Lavenex, S., Flavia J., Terri G. and Ross B. 2015. Regional Migration Governance. In Tanja A. Börzel/Thomas Risse (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lindgren, D., Uaumnuay, T. and Emmons, K. 2018. Improved Labour Migration Governance to Protect Migrant Workers and Combat Irregular Migration in Ethiopia Project

Mehari M. 2020. How and why migration is weaponised in the relations between Africa and Europe.

Norwegian Refuge Council (NRC). 2014. Living out of Camp: Alternatives to Camp-based Assistance for Eritrean Refugees in Ethiopia.

Norwegian Refuge Council (NRC). 2015. NRC Urban Multi-Sector Assessment of Eritrean Refugees in Addis Ababa.

Olivier, M. 2017. Training of Trainers Manual: National Labor Migration Management Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: IOM.

OXFAM. 2020. The EU Trust Fund for Africa: Trapped between Aid Policy and Migration Politics.

RMMS. 2014. Blinded by Hope: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Ethiopian migrants. Nairobi.

RMMS. 2016. Young and on the Move: Children and Youth in Mixed Migration Flows within and from the Horn of Africa.

RMMS. 2017. Unpacking the Myths: Human smuggling from and within the Horn of Africa. Danish Refugee Council

RRP. 2020. Ethiopia Country Refugee Response Plan. https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/Ethiopia%20CRP%202020-2021.pdf

Tardis, M. 2018. EU Partnership with Africa Countries on Migration: A Common Issue with Conflicting Interests. IFRI.

Tinajero, A. 2014. MIGRATION MANAGEMENT?Accounts of agricultural and domestic migrant workers in Ragusa (Sicily). eLivres de l’Institut

Tsion T. (2018). Promises and Challenges of Ethiopia’s Refugee Policy Reform. Institute of Security Studies: Addis Ababa.

UNHCR. 2017. Ethiopia Country factsheet (December)

UNHCR. 2018. UNHCR Factsheet-Ethiopia (February)

UNHCR. 2020. UNHCR Factsheet-Ethiopia (February)

UNHCR. 2022. UNHCR Factsheet-Ethiopia (February)

World Bank. 2022. Ethiopia data - www.data.worldbank.org

Yordanos E. 2015. The Political Economy of Transnational Social Networks and Migration Risks: The Case of Irregular Migrants from Southern Ethiopia to South Africa. MA Thesis: University of Oldenburg.

Yordanos E. and Tanya Z. 2020. Migration Barriers and Migration Momentum: Ethiopian Irregular Migrants in the Ethiopia-South Africa Migration Corridor. REF

Legal Frameworks

Djibouti Declaration on Refugee Education (2017)

Employment Exchange Service Proclamation 632/2009

EU–Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative (Khartoum Process)

Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development (Rabat Process)

Investment Proclamation No 280/2002

Investment Proclamation No. 769/2012

Joint Africa–EU Declaration on Migration

Joint Africa–EU Partnership on Migration, Mobility and Employment (Tripoli Process)

Kampala Declaration on Jobs, Livelihoods and Self-Reliance

Migration Action Plan (MAP) (2015-2020)

Migration Policy Framework for Africa (MPFA) (2018-2030)

National Coordination Mechanisms on Migration (NCM)

National Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons

Overseas Employment Proclamation (923/2016)

Overseas Employment Proclamation Amendment (No. 1246/2021)

Refugee Proclamation No.409/2004

Refugee Proclamation No. 1110/2019

Notes

[1] Figure - International migrant stock (% of population) Ethiopia - www.data.worldbank.org

[2] Article on ethiopia.iom.int - Over 800,000 Ethiopians migrated abroad in the past 5 years - Labour Migration Survey Finds

[3] What is Migration Management - www.igi-global.com

[4] A proclamation to provide for employment exchange services - www.chilot.me

[5] Proclamation No. 923/2016 - Ethiopia’s overseas employment proclamation

[6] Proclamation No. 1246/2021 - Ethiopia’s Overseas Employment Proclamation - www.lawethiopia.com

[7] Proclamation No. 909/2015 Prevention and Suppression of Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants Proclamation - www.africanchildforum.org

[8] Directives are legislative acts adopted from proclamations, which are not self-executing and general. Directives are usually addressed to implement proclamations.

[9] ethiopia_trafficking_2015_en.pdf - www.africanchildforum.org

[10] Article on www.ena.et - Government Finalizing Migration Policy

[11] Total Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Ethiopia (31 Aug 2022 ) - www.data.unhcr.org

[12] Statement on the situation of Eritrean Refugees in Ethiopia - www.ethioembassy.org.uk

[13] Proclamation No. 409/2004, Refugee Proclamation - www.chilot.me

[14] Proclamation no. 1110/2019 refugees proclamation - www.chilot.me

[15] According to the national diaspora policy, this means Ethiopians or foreign nationals of Ethiopian origins residing outside of Ethiopia.

[16] Proclamation No. 280/2002 - Re-Enactment of the Investment Proclamation - theiguides.org

[17] Proclamation No.769 of 2012 - A Proclamation of investment - www.ethiopianembassy.org.in

[18] Diaspora policy - www.ethiopianembassy.org.in

[19] Diaspora Policy English - www.ethioembassy.org.uk

[20] Proclamation 270/2002 - Providing Foreign Nationals of Ethiopian Origin with certain rights to be exercisedin their country of origin proclamation - www.refworld.org

[21] https://migration.merit.unu.edu/research/projects/connecting-diaspora-for-development-cd4d/

[22] Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA) www.arra.et

[23] Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018 – 2030) - www.au.int

[24] IGAD is is a body currently comprising seven countries in the Horn of Africa. The aim of the organisation is to assist and complement the efforts of the member States to achieve, through increased cooperation: food security and environmental protection, peace and security, and economic cooperation and integration in the region. Member states are: Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda.

[25] AU/ILO/IOM/UNECA Joint Programme on Labour Migration Governance for Development and Integration in Africa - www.ilo.org

[26] IGAD-Migration Action Plan - www.iom.int

[27] Regional Consultative Processes on Migration - www.iom.int

[28] National Co-Ordination Mechanism On Migration (NCM) - www.immigration.go.ke

[29] Djibouti Plan of Action on Refugee Education in IGAD Member States - www.globalcompactrefugees.org

[30] Kampala declaration on jobs, livelihoods and self-reliance for refugees, returnees and host communities in the IGAD region - www.acbc.iom.int

[31] Joint africa-eu declaration on migration and development - www.au.int

[32] Tripoli Process (Joint Africa-EU Declaration on Migration and Development) - www.iom.int

[33] The Khartoum Process - www.khartoumprocess.net

[34] Promoting safe, orderly, and regular migration from and within the Horn of Africa - www.giz.de

[35] Stemming Irregular Migration in Northern & Central Ethiopia-SINCE - www.ec.europa.eu

[36] Resilience Building and Creation of Economic Opportunities in Ethiopia (RESET II) www.ec.europa.eu

[37] Regional Development and Protection Programme in Ethiopia - www.ec.europa.eu

[38] The number of migrants to Europe is lower than nationals traveling to other destinations such as the Middle East and South Africa.

[39] Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA) www.arra.et

Kiya Gezahegne

Oliver Bakewell