National and international migration policy in Lebanon

About the EFFEXT background papers

2.1 Lebanese migration context

2.1.1 Lebanon as a country of emigration

2.1.2 Lebanon as a refugee host state

2.1.3 Lebanon as a state for migrant workers

2.2 Migration governance structure

Table 1: Overview of decrees and laws managing immigration policy in Lebanon

2.3.3 Emigration and Diaspora policy

2.3.4 Internal migration policy

2.3.5 Refugee and asylum policy

2.3.6 Return and readmission policy

3. International migration policy relations

3.1.1 UNHCR-Lebanon policy relations

3.1.2 EU-Lebanon migration policy relations

EU-Lebanon Association Agreement (AA)

EU-Lebanon Action Plans (2007-2020)

3.1.4 Relations between EU migration policy and Lebanese migration policy

How to cite this publication:

Robert Forster, Are John Knudsen (2022). National and international migration policy in Lebanon. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (EFFEXT Background Paper )

This EFFEXT Background Paper provides a brief presentation of migration and migration policy dynamics between the European Union (EU) and Lebanon. It presents an overview of key Lebanese national and international migration policies and outlines the domestic migration governance structures within Lebanon. In terms of international relations, the paper primarily focuses on Lebanon's regional and European collaboration. The Background Paper concludes with a short reflection on key questions that need to be explored when studying the effects of EU migration management in Lebanon.

About the EFFEXT background papers

The Effects of Externalisation: EU Migration Management in Africa and the Middle East (EFFEXT) project examines the effects of the EU’s external migration management policies by zooming in on six countries: Jordan, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Senegal, Ghana and Libya. The countries represent origin, transit, and destination countries for mixed migration flows, and differ in terms of governance practices, state capacities, colonial histories, economic development and migration contexts. Bringing together scholars working on different case countries and aspects of the migration policy puzzle, the EFFEXT project explores the broader landscape of migration policy in Africa and the Middle East.

The EFFEXT Background Papers guide the fieldwork, case selection and analysis of migration policy effects in the EFFEXT project’s case countries. The papers are based on desk-reviews of scientific literature and grey literature, the latter including government documents, governmental and non-governmental reports, white papers and working papers.

Introduction

Lebanon is located in the Eastern Mediterranean and has a population of between 5.2 to 7 million. The country has a long history of migration, both receiving migrants from abroad as well as having a large diaspora population.

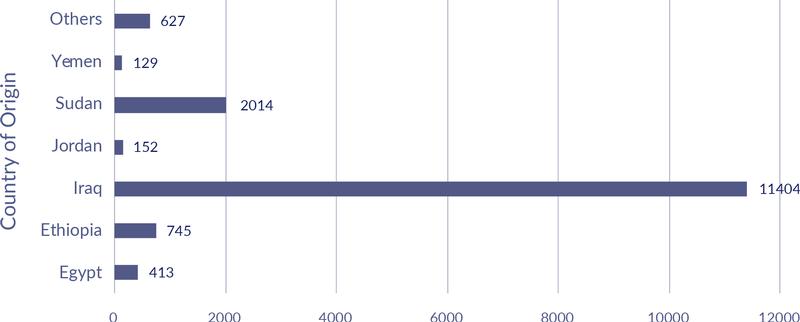

Lebanon is known as a country of emigration, as a refugee host state, and as a destination for migrant workers. Approximately 4-14 million Lebanese currently live abroad, but there are no official statistics on emigration. According to official statistics from United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA), 422,188 Palestinian refugees reside in Lebanon. Additionally, a 2020 survey from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) counted 11,404 Iraqis in Lebanon and some 2,014 Sudanese, refugees, asylum seekers, and ‘others of concern’. In addition, approximately 400,000 migrant workers live in Lebanon.

This report explores the key areas of cooperation in EU-Lebanon migration policy. First, the report frames the types of migration to-and-from Lebanon that define the country’s priorities: (1) Lebanon as a state of emigration; (2) as a host state of refugees; and (3) Lebanon as a host state for migrant workers. Lebanon’s institutional framework for migration governance is thus unpacked in addition to policy considerations within the various aspects of immigration, border control, emigration, the diaspora, internal migration, asylum and return and readmission.

The second part of the report focuses on the policy framework guiding the interactions between Lebanon and the EU, including Lebanon’s other multilateral regulatory frameworks; linkages between Lebanon and the UNHCR; a brief history of EU and Lebanese policy relations; and a breakdown of current EU-Lebanese policy discussions and frameworks from 2002-2022. The report concludes with a short reflection on key questions that need to be explored when studying the effects of EU migration management in Lebanon.

National migration policy

2.1 Lebanese migration context

Three factors currently determine the migration context in Lebanon: as a country of emigration; as a refugee host state; and as a destination for migrant workers. Each aspect is explored in greater depth below.

2.1.1 Lebanon as a country of emigration

Despite 4-14 million Lebanese currently living abroad, there are no official statistics on emigration and no government agency keeps track of the diaspora (Hourani and Shehadi, 1992; G. Hourani, 2007; AlKantar, 2016).[1]

Since 1860, there have been ebb and flow in migration from Lebanon:

- The first mass exodus was in the late nineteenth century (1865-1919) when more than 300 000 (a third of the population) left. Numbering3000 per year between 1860-1900 and increasing to 15 000 per year between 1900-1914 (Labaki and Abu Rjaili 2005, p. 59 in Tabar, 2010, p. 3-4).

- Immigration decreased after 1929 due to the global recession, however, a smaller wave of migration took place between 1945 and 1975, when a total of 63,000 people emigrated from Lebanon (Tabar, 2010, p. 4).

- The second mass exodus was during the civil war between 1975 and 1990 when 680 000-990 000 people left (Tabar, 2010, p. 5; Ajluni and Kawar, 2015, p. 17). Before 1980, it was mostly unskilled labourers migrating and permanently settling in developed countries. After 1980, migration was driven by increased education and a lack of jobs in Lebanon.

- The third wave was between 1991 and 2009 and involved approximately 220 000 – 400 000 people.[2] In the post-war period, the diaspora served as a key source of revenue for Lebanon. Most Lebanese migrants are men, especially to the Gulf, whereas to Western countries, it is mostly families that emigrated. The three most important destinations for Lebanese émigrés are the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (40%), North America (23%) and Europe (21%) (De Bel-Air, 2017, p. 6). Emigration in search of employment predominates, reflecting global migration flows (Audebert and Doraï, 2010).

- Net migration from Lebanon shrank between 2009–12, but economic collapse and successive ongoing political crises after 2019 caused a fourth wave of migration. The World Bank predicted that crisis recovery will take between 12-19 years (World Bank, 2020). In late 2021, a donor conference pledged USD 300 million, but the country’s economy will not recover unless sweeping reforms are enacted. The migration rate in 2021 was -91 per 1000 compared to -21 per 1000 in 2017 (CIA, 2021: Chaaban et al. 2018, p. 4).

Figure 1: Net (Im)migration from Lebanon, 1960-2017

Source: (Ajluni and Kawar, 2015, p. 17; World Bank, 2019

2.1.2 Lebanon as a refugee host state

According to official statistics from United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA), about 422,188 (2009 estimate)[3] Palestinian refugees live in Lebanon following forced migration and settlement in the wake of successive Arab-Israeli conflicts in 1948, 1967, and 1973, as well as conflicts between armed Palestinian factions and their host states, such as Black September in Jordan in 1970.[4] A survey by the Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee tallied 224,901 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon distributed in the camps (45%) and the gatherings (55%) (LPDC 2018, p. 18). There are currently twelve Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, the majority in or near the urban centres of Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon and Tyre. Some Palestinians (mostly Christians) received Lebanese citizenship at intervals after 1948. The remainder, who are primarily Sunni, are subject to restrictions that intensified after 1990, including limitations on residency, employment, and property ownership (Knudsen, 2010).

Figure 2: Location of Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon

Palestinians are the most protracted refugee group in Lebanon and were joined by other groups of refugees and asylum seekers over the decades. In 2020, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) counted around 11,404 Iraqis in Lebanon up from around 6,000 in 2017 (Chaaban et al. 2018, p. 5). The UNHCR (2020) listed some 2,014 Sudanese refugees, asylum seekers, and ‘others of concern’ in Lebanon in 2020.

Lebanon’s status as a refugee host state was cemented after 2011 when Syrians began seeking refuge from the Syrian conflict, leading to the largest demographic change in Lebanon’s history. By August 2014, the number of Syrian refugees, termed ‘displaced’ by the Lebanese government, swelled to over one million, this reduced to 850, 000 by January 2021. However, this number does not include the estimated 34,000 Palestinian Refugees from Syria (PRS), which are counted as a distinct category. Since 2014, Lebanese politicians were unified in their stance to limit the ability of Syrians to stay in Lebanon, and this was accompanied by a change in policy towards refugees first implemented starting in January 2015. After successive crises, Lebanon’s Minister for Displacement Issam Sharaf El-Din, announced during July 2022 that the government planned to repatriate 15,000 Syrians per month (Chaccour 2022), a move decried as unsafe and unlawful (HRW 2022).

Figure 3: Number of refugees, asylum seekers and ‘others of concern’ (unhcr, 2020)[5]

2.1.3 Lebanon as a state for migrant workers

There is a population of 400,000 migrant workers living in Lebanon that have residency through the kafala (sponsorship) system (IOM, 2015). This group is divided into two groups: high-skilled workers predominantly from Western and other Arab states, and an estimated 250,000 domestic migrant workers.[6] Domestic migrant workers are subject to limited rights under Lebanese labour law, leading to concerns of widespread exploitation (HRW, 2020). More detail is provided on the rights of migrant workers and the kafala (sponsorship) system below.

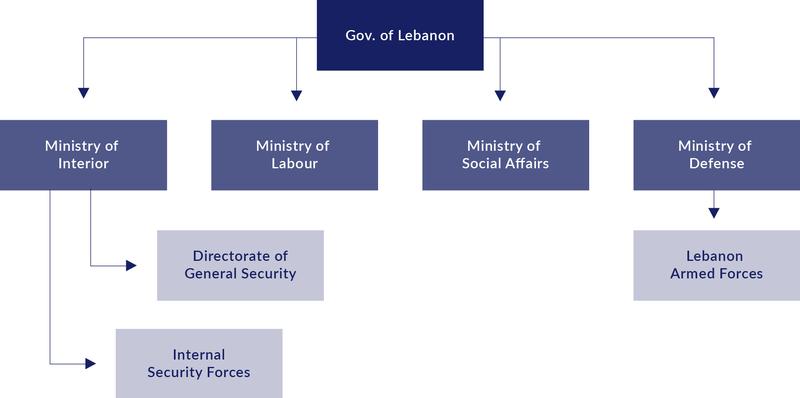

2.2 Migration governance structure

Lebanese legislation regulating immigration was passed in 1962 and the 1925 nationality law was last amended in 1960 (Sensenig-Dabbous, 2011, p. 30). Decisions related to immigration are often taken on the administrative or bureaucratic levels rather than through legislation. Immigration law is enforced by the Directorate of General Security (al-amn al-‘am) a branch of the Ministry of Interior. The Ministry of Interior is the main actor responsible for immigration law, however the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Ministry of Labour have decision making abilities in relation to migrant workers. There is no local level migration governance[7] and governorates and districts are responsible for border security (in conjunction with the Lebanese Army) and law enforcement (European Committee of the Regions, n.d.).

Emigration policy is governed by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Emigrants (MFAE) established in its current structure by Law No. 247 of 2000. The Ministry has two directorates with the mandate of providing for Lebanese citizens abroad: the General Directorate of Emigrants are tasked with outreach to boost “cultural and educational bonds with Lebanese nationals abroad” and encourage investment in Lebanon; the Directorate of Political and Consular Affairs deals with administrative issues including passports, voter registration, personal status issues and information on investments (Tabar and Denison, 2020, p. 202) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Governance structure addressing Lebanese émigrés

2.3 Migration policy areas

Immigration and emigration are a delicate matter in Lebanon and are linked to nationality and election laws. This is due to the relationship between these phenomena and the system of confessional power-sharing on which the country’s political settlement was founded in 1943 after the French mandate period. The arrangement was subsequently re-negotiated in the Taif Accord of 1989, granting increased power to Muslim groups. This agreement is the foundation of Lebanon’s post-war political settlement but has been under strain as highlighted by stalled reform of the electoral law as well as the negotiation of the Doha Agreement in 2008 (a brokered political agreement between March 8 and March 14 following clashes). Because of such political limitations, immigration is regulated through administrative and executive actions, rather than legislation.[8] In turn, this exposes policies regulating immigration restrictions, naturalisation, and asylum, to political manipulation.

2.3.1 Immigration policy

Immigration regulations are mostly linked to either the category of visa (labour group) or nationality. Lebanon is not a signatory of the 1990 Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. Moreover, Lebanon has ratified 7 of 8 fundamental conventions of the International Labour Organization but has not ratified conventions providing for the protection of migrant workers (Chaar, 2021, p. 1; ILO, 2022).

Table 1: Overview of decrees and laws managing immigration policy in Lebanon

|

Legal framework |

Date |

Content |

|

Legislative decree no. 10188 Decision no. 320 |

28 July 1962 2 August 1962 |

Provide the legal framework governing the entry and exit of foreigners from Lebanese border posts (Sensenig-Dabbous, 2011, p. 31.) |

|

By-Law No 1 7561 |

1964 |

Regulates the work of foreigners in Lebanon |

|

Decision no. 621/1 |

1995 |

Regulates occupations reserved for Lebanese nationals |

|

Decree No. 4186 |

2010 |

Provides an amendment to Decree no. 10188 giving husbands and children of Lebanese women the right to 1-3 years residency permits |

|

Law No. 129 |

2010 |

Provides an amendment to Article 59 of the Labour Code of 1946 defining Palestinians as ‘foreigners’ |

|

Law No. 164 |

2011 |

Provides an anti-trafficking regulation. |

|

Sources: Sensenig-Dabbous, 2011, p. 31 and UN-Habitat, 2018, p. 15. |

||

There is a hierarchy dependent on nationality and worker category that determines the privileges of migrants. Among workers from Jordan and the GCC member states, entry is permitted for 3-6 months with extension up to a year free of charge.[9] From 78 countries, a one-month tourism visa is granted on entry with a free 3-month extension. Special regulations pertain to female visitors aged between 17-35 from 28 countries in East and Central Asia, in addition to Central and Eastern Europe, the Baltic, and the Balkans. Citizens “from countries exporting workers,” i.e. 56 countries in Africa, Central and East Asia and the Caribbean, must get authorization from General Security before entry into Lebanon (General Security, n.d.). Eleven Arab and five African states have less restrictions on tourism visas. Female citizens from Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Ghana, and Sierra Leone cannot work as domestic workers in Lebanon due to legislation in their home countries. Lastly, special authorisation from General Security is required for: holders of Palestinian passports from Jordan; domestic workers or bodyguards of non-Lebanese diplomatic families not from the GCC; artists; foreigners that wish to work; individuals presumed to be terrorists or indicated to be so by Interpol; and holders of ‘emergency passports’ (General Security, n.d.).

Box One: The Kafala system

The kafala system (sponsorship) is a means through which migrant workers can find work and reside in Lebanon. The relationship between the employer, prospective migrant, and the Ministry of Labour is often facilitated through a recruitment agency. The system requires that the migrant is legally bound to an employer (kafil) and there are limitations on entry/exit into Lebanon as well as complications related to changing sponsor, which requires written permission. Through the kafala system, a work permit is issued by the Ministry of Labour on an annual basis and residency is managed by General Security. The system has been criticised by human rights groups. If a migrant worker leaves their employer, the latter may file a spurious criminal complaint against the migrant worker with General Security releasing the sponsor of any responsibilities for the migrant worker and their residency status. The migrant worker, now without legal residency, is subject to an arrest warrant, which effectively bars their departure from Lebanon by legal means due to threat of arrest.

The 1964 Lebanese Labour Code regulates the employment of migrant workers, but article 7 of the Code excludes domestic workers, “thereby denying them the protection [afforded] to other categories of workers.” This means that domestic workers are reliant on the kafala system to find work and get residency (see Box 1) (ICJ, 2020, p. 14). Bilateral arrangements facilitating the mobility of migrant workers are in place for Egypt, Iraq, and the GCC countries (Senesig-Dabbous, 2010, p. 19). From 1994 to 2014, there was a bilateral agreement in place with Syria allowing for freedom of movement, residency and employment. The Lebanese-Syrian socio-economic agreement was amended by the 2014 Policy on Syrians that restricted their rights significantly and make many Syrians also dependent on a sponsor. Restrictions imposed by the kafala system means that many migrant workers made their way into Lebanon via Egypt or Syria and reside illegally. Following the financial crisis from 2019 onwards, economic migrants can no longer secure employment in Lebanon and many wish to return to their home countries. However, in order to leave, they may be required to pay a penalty of 650,000 Lebanese Lira due to irregular residency status (about $430 USD pre-2019, around $32 in February 2022), in addition to the fare for the plane ticket.[10] Such penalties may be lifted through cooperation between General Security and country embassies. Sudan for instance has lifted this penalty for 1,000 of its citizens (Dagher, 2020).

Another exceptional aspect of the 1925 Nationality Law is that children inherit the citizenship of their father, regardless of the citizenship of their mother. Human Rights Watch has claimed that this arrangement is “discriminatory” and “affects almost every aspect of the children’s and spouses’ lives, including legal residency and access to work, education, social services, […] health care” and inheritance (HRW, 2018). An estimated 77,400 are impacted across social classes (Saharafeddine, 2017, p. 15).

2.3.2 Border control policy

Lebanon borders two states: Israel to the South and Syria to the east and north. Both bordering states have occupied parts of Lebanese territory after 1976. Israel withdrew its troops from the area south of the Litani river in 2000, and Syria withdrew its troops in April 2005. There are no legal crossings on the Lebanese-Israeli border and it is illegal for Lebanese nationals to visit Israel. Foreigners may be refused entry into Lebanon if they have Israeli visas in their passports (FCDO 2022). The Lebanese-Syrian border has four legal crossings, the largest of which is al-Masnaa on the Beirut-Damascus road. The Anti-Lebanon Mountains, a mountain range in Syria, form a natural border between Lebanon and Syria in the north. These mountains have long been used for cross-border smuggling which sustains many of the villages otherwise subject to higher prices on Lebanon’s periphery (Hutson and Long, 2011).

2.3.3 Emigration and Diaspora policy

The exact size of Lebanon’s diaspora is unknown and is a political concern due to potential implications on electoral politics. The diaspora is characterised as “entrepreneurial” as well as “conflict induced” and varying in skill levels (Fakhoury, 2018). A 2014 estimate suggested that around 885,000 first-generation emigres or persons born in Lebanon were currently living outside of Lebanon. These people were distributed across the Gulf states (41%); North America (21%); Europe (21%); and other countries, such as Australia and Brazil (16%) (Tabar and Denison, 2020, p. 200). There are two key areas of diaspora engagement: (1) investment in Lebanon and the matter of remittances, and (2) voting and naturalisation.

Formal relations with the diaspora are managed primarily through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants which maintains a network of embassies and consulates. The MFAE facilitates numerous outreach activities to Lebanese communities to strengthen ties between émigrés and Lebanon. Additionally, the Lebanese diaspora engage Lebanon’s politics, business, and development through informal channels (Fakhoury, 2018). A central aspect of the relationship relates to remittances. Over ten years between 2003 and 2013, remittances increased from USD $2.7 billion to USD $6.9 billion (16 % of GDP) (Ghobril in Hourani, 2007, p. 6; Ajluni and Kawar, 2015, p. 19). According to the World Bank, remittances to Lebanon increased by 6.31 % from 2018 to 2019 with a decrease in 2020 due to the global corona virus pandemic and weakened confidence in Lebanese banks (Aziz, 2021). Attracting investments from Lebanese living abroad shaped priorities in the Lebanese economy. For instance, the luxury properties built in the 1990s and 2000s to attract foreign investment did little to alleviate Lebanon’s housing crisis and many apartments were left empty for most of the year benefiting from the tax exemption on unoccupied apartments (Interview by author, senior member of Lebanese Order of Architects and Engineers, July 2021).

Figure 5: Lebanese governance structure addressing immigration

The Investment Development Authority of Lebanon (IDAL) was established to increase investments from Lebanese living abroad. They are also responsible for managing bilateral ‘Promotion and Protection of Investment agreements’ with Canada, France and Germany that maintain “favourable investment conditions through contractual protection of such investments” (Tabar and Denison, 2020, p. 205). Since 2014, the Lebanese Diaspora Energy, an initiative by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants, “founded various platforms to facilitate the diaspora’s contributions to Lebanon’s development” (Fakhoury, 2018). Remittances and lobbying by Lebanese nationals abroad have also mobilized the funding of reconstruction efforts in Lebanon following conflict and the Beirut port explosion in August 2020. The United Nations also established prominent initiatives such as the Transfer of Knowledge Through Expatriate Nations (TOKTEN) and LIVE Lebanon, which seek collaboration and exchange in the areas of capacity building, governance, and other development areas (Ibid.).

The 2008 Parliamentary Election Law gave Lebanese nationals abroad the right to vote either online or through embassies and consulates. Access to Lebanese nationality for descendants of émigrés was simplified in 2015. In 2018, over 45,000 votes were cast from abroad. Some political parties – the Lebanese Forces, Free Patriotic Movement and the Syrian Socialist National Party – were particularly effective in engaging their constituencies in the diaspora through online platforms, mobile phone applications, and other means (Tabar and Denison, 2020, pp. 203-204). In 2018, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants announced that there would be six Parliamentary seats for the diaspora. Thus, there is greater opportunity for Lebanese émigrés to facilitate political change in Lebanon (Tabar and Denison, 2020, p. 213). This is particularly when considering that higher levels of education and income are found among large sections of the diaspora, exceeding national averages (AlKantar, 2016). In the 2022 election, the number of Lebanese diaspora registered to vote tripled from the 2018 election encouraged by civil society and activism worldwide and the economic and political crises taking place since 2019 (Dagher, 2022, p. 2).

2.3.4 Internal migration policy

Internal migration in Lebanon is fuelled by two phenomena. First, internal migration is the product of largescale rural-to-urban migration that began in the 1920s and has led to the rapid urbanisation of Lebanon fuelled by industrialisation and increased availability of employment and social mobility. In 2016, an estimated 67 % of the population live in the main urban centres, and 89 % live in urbanized areas.

Second, urbanisation and internal migration was catalysed by forced internal displacement during the 1975-1990 civil war in addition to smaller and shorter conflicts between Hezbollah and Israel (1993, 1996, 2006); conflicts in Tripoli (2008, 2011-2014); and clashes between the Lebanese Army and armed groups in the Palestinian camps and urban centres (such as, the Nahr al-Barid Camp in 2007, Sidon in 2013, Tripoli in 2014). Most internal displacement occurred during 1975-1990 civil war when 23% of the population was impacted. To rectify war-time displacement the National Return Policy was adopted in 1993 and implemented by the Ministry for Displacement and the Central Fund for the Displaced. The policy used the strategies of (1) material compensation for damages and/or to vacate squatted buildings, (2) ‘reconciliation’ through locally mediated agreements, (3) the reconstruction of infrastructure and (4) provision of services (Forster, 2022). Other bodies engaged in implementing reconstruction and development strategies linked to but not directly addressing internal displacement including the Council of the South, the Higher Relief Council, and the Council for Development and Reconstruction.[11] These strategies aimed primarily at returning displaced populations to villages of origin as a means of reversing sectarian enclaving during the conflict. A lack of services and employment in the countryside, as well as prolonged displacement and creation of established communities in the cities meant that few returned except the elderly. As of 2022, the Central Fund for Displacement and the Ministry for Displacement remain[12] but their track record is marred by corruption, bribery, mismanagement, and political manoeuvring (Leenders, 2012, 218-222). The National Return policy is generally considered a failure by observers and academics because it did not initiate return; did not recognise that rural-to-urban migration would have been likely to occur despite of the conflict; and it catalysed slum creation in the post-war period due to the demand for cheap housing in urban areas, especially South Beirut (Sawalha, 2010; Leenders, 2012).

Internal migration has been a challenge to governance in Lebanon because the Lebanese political system is based on maintaining a sectarian balance enshrined in the 1943 National Pact and reconfigured in the Taif Agreement of 1989. As a result, elections rely on ancestral voting whereby internal migrants are registered on the territorially-linked electoral rolls of their grandparents which may be geographic areas and villages where a person has never lived (Abu-Rish, 2016). This has resulted in the disenfranchisement of voters, especially the urban poor, who reside in areas where they have no ability to influence representation through the polls.

Another aspect of internal migration includes the Lebanese segment of the ethnic Dom population, a formerly peripatetic (non-food producing nomadic people) living across the Middle East and North Africa (Kırkayak Kültür, n.d.). Now predominantly a settled population, there are 3,112 Dom living in South Lebanon and Beirut living in marginalised areas and in communities characterised by low development indicators (Diab and Saban, 2022). The Dom community in Lebanon was joined by their close Syrian counterparts after 2011. There were an estimated 37,000 Dom in Syria before the conflict, many with strong familial ties across the Lebanese-Syrian border. The Dom communities’ access to services in Lebanon increased after a portion of the community were naturalised in accordance with the 1994 Naturalisation Law (Diab and Saban, 2022).

2.3.5 Refugee and asylum policy

Lebanon is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention on Refugees nor its affiliated 1967 protocol. Additionally, the country does not consider itself a country of asylum but sees its position as a transit country. Lebanon also has no domestic asylum legislation (Janmyr, 2017). In 1948, Lebanon received 110,000 Palestinian refugees, a number that grew after the Arab-Israeli conflicts in 1967 and 1973. The intricacies of Palestinian refugee policy are outlined below. In addition, Lebanon has been the destination for displaced Iraqis after 2003 and displaced Syrians after 2011. Iraqis usually entered Lebanon illegally and did not receive any form of recognised protective status in Lebanon despite calls for their recognition first under ‘temporary protection’ and later as ‘prima facie’ refugees. The lack of status exposed Iraqis in Lebanon to refoulment, often using prolonged arbitrary detention to encourage ‘voluntary return’ (Trad and Frangieh, 2007). A similar response maintains that Syrians do not have the right to asylum in Lebanon. However, between 2011 and December 2014 Syrians were subject to an open-border policy due to the 1994 socio-economic agreement with Syria that did not change until the Policy on Displaced Syrians was implemented in January 2015.

Despite the initial push for establishing camps in response to Syrian displacement, the Lebanese government refused in light of their experience with Palestinian camps and Palestinian militancy. Informal settlements developed in rural areas subject to building restrictions and impermanence. The situation for self-settled Syrians in Lebanon gradually deteriorated due to restrictions on employment, residency, and mobility (Mourad, 2017). The expense of residency or the need to acquire a sponsor has been financially untenable for the vast majority of Syrian households and the number of Syrians with legal residency has been decreasing annually since 2015.[13] There is substantial political, economic, and social pressure for Syrians to leave Lebanon, fuelled by the economic crisis and widespread xenophobia. Randomised survey experiments among Lebanese and Syrian households that consider migrating from Lebanon find that both push and pull factors account for migration aspirations, yet the pull factors – especially employment opportunities – continue to be more salient (Hager, 2021). Interview-based small-sample studies from camp-based Syrian refugees in the Bekaa valley find that they carefully weigh their options for migration and are ambivalent about leaving Lebanon for Europe (Tyldum, 2021). In retrospect, many regret their decision to stay, indicating the importance of time and temporality in migrants’ decision-making.

Palestinian Refugees

Palestinians have resided in Lebanon since 1948. As UNRWA refugees Palestinians in Lebanon lack basic civil rights and face restrictions on integration and permanent settlement. Palestinian refugees have a long history of overcoming migration obstacles and engaging in transnational migration with transnational kinship networks spurring emigration to Europe (Doraï, 2008). However, as UNRWA refugees, they cannot access any of the UNHCR’s “durable solutions”. Their travel documents (laissez passer) provide access to Europe (Schengen) under certain conditions, yet options for asylum are slim and they are routinely denied entry and deported.

The size of the Palestinian population in Lebanon is contested. In 2017, the government’s door-to-door census placed the population at about 200,000, about half of the official UNRWA estimate of around 420,000 refugees in the country (LPDC, 2018, p. 18). About 50% of the Palestinian population live in refugee camps, in addition to 42 ‘gatherings’ out of the camps (UN-Habitat, 2014). The camp structure has mixed origins, with some established for earlier waves of Armenian and Syriac refugees in the 1920s and 1930s. Others were established in 1948 or in the years after. The Lebanese civil war from 1975 to 1990 saw the destruction of several camps near Beirut and Mount Lebanon (Fawaz and Peillen, 2003). In 2007, the Nahr al-Bared camp was destroyed in a three-month battle between the Salafi jihadi group Fatah al-Islam and the Lebanese Army and is yet to be fully rebuilt (Knudsen, 2018). Although ostensibly ‘Palestinian’, the camps are integrated into wider housing markets and are home to mixed populations including working class Lebanese nationals, Syrian refugees, migrant workers, and other groups.

Lebanon’s political parties are unified in their prevention of naturalisation and settlement of Palestinians in Lebanon: conditions enshrined in the 1989 Taef Agreement. Tawtin or naturalisation and integration into the Lebanese state is also opposed by many Palestinians on the grounds that it contravenes the ‘right to return’ to Palestinian land occupied by Israel and is therefore a central ideological component in the Palestinian struggle. Nonetheless, there have been waves of naturalisation. Between 1949-1958, 31,000 Palestinians received Lebanese citizenship, including 3,000 Palestinian Muslims. Naturalization continued through the 1960s, although the exact number is unknown. During the 1950s and 1960s, there were an estimated 50,000 naturalisations among mostly wealthy families originating from Palestinian cities. In 1994, Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri issued the Naturalisation Decree which provided citizenship to over 150,000 foreigners, including 32,504 Palestinians (Ghandour, 2018, p. 92). There are claims that naturalisation prioritizes Palestinian Christians as a means of bolstering the size of the Christian population in Lebanon (Halabi, 2004, p. 40).

For non-naturalised Palestinians, however, regulations are encouraged by security concerns and political disenfranchisement. This was partly motivated by the assumption among some Lebanese political factions that the militarised Palestinian factions were to blame for the outbreak of the civil war in 1975 (Bulloch, 1977). Hezbollah has paid lip service in support of the Palestinians as a bastion of the resistance but has not extended political and parliamentary support in their favour for lifting legal restrictions on labour, property ownership, or employment. In 2001, the parliament passed a new law excluding Palestinians from owning, bequeathing, or registering property. Those who owned property before 2001 cannot pass it on to their children because their property is no longer inheritable. To circumvent the law, Palestinians either do not register their property or rely on informal systems of ownership (Hajj, 2016). Attempts to improve the situation for Palestinian refugees have been instituted by ministerial decrees, which, unlike laws passed by parliament, can be overturned by incoming governments (Knudsen, 2009).

Syrian displaced persons

Syrian refugees are officially termed nazihun or ‘displaced’ by the Lebanese government and do not have the right to asylum (Janmyr, 2017). Contemporary Syrian-Lebanese relations occur against the backdrop of historically integrated relationships based on trade, religious, and familial linkages, particularly in the North, where the Plain of Akkar provided passage to the interior cities of Homs, Hama, and Damascus (Pipes, 1990). Syrian migrant workers began arriving en masse in Lebanon in the 1950s, and seasonal labour migration became established by the 1980s (Chalcraft, 2008, p. 148). Before 2011, there were a few hundred thousand Syrians in Lebanon. The regulation of migration between 1994 and January 2015 was enshrined in a 1994 bilateral agreement that granted entry and residency in Lebanon on the provision of a Syrian national identity card. Escalating conflict in Syria saw the number of border crossings rise in March 2011. Initial efforts to address the refugee influx were organized by the UNHCR together with the Lebanese emergency agency, the High Relief Council. Initially, about half of the Syrians rented apartments (44.4%), while the remainder settled in substandard buildings (34.6%) and and informal settlements (18.4%) (UN-Habitat and AUB 2015). This strategy was informed by the no-camp policy which aimed to avoid repeating the Palestinian protracted camp presence. By August 2014, over a million Syrians were registered in Lebanon and in response, the Lebanese Government ordered the UNHCR to stop registration. In parallel, host-refugee relations soured in the face of a contracting economy with soaring unemployment and lack of affordable housing . In October 2014, the Council of Ministers issued the Policy on Syrians restricting access into Lebanon. In October 2014, the Council of Ministers issued the Policy on Syrians restricting access into Lebanon.

The result has been a diversification of legal status and an increase in irregular entry and illegal residency among Syrians in Lebanon (Janmyr and Mourad, 2018). Restrictions on entry at border points define the available visas and has been reduced to ten main categories: tourism; business; property owner; tenant; student; transit; medical visits; embassy appointments; displacement (under extraordinary circumstances determined by the Ministry of Social Affairs); and sponsorship (UNHCR, 2020b). Ultimately, most Syrians seeking residency do so through sponsorship, which requires the payment of an annual fee of LBP 300,000 for each family member over 15 years of age.[14] This is untenable to many households, pushing families further into debt due to difficulties in gaining regular employment. The policy towards Syrians has been criticized for being opaque and arbitrary in implementation. As highlighted by the Lebanese organization SAWA for Aid and Development, the announced waiver of residency fees for Syrians in 2017 was not implemented uniformly across the offices of General Security or its employees (Mhaissen and Hodges, 2019, p. 7). In response to the refugee influx the EU increased development funding to Lebanon on the condition that it serves both Lebanese and Syrian communities (among others) (see Part II).

Examples of forced return of Syrian refugees to Syria (refoulement) were reported in the press. In May 2019, the government announced that all Syrians arriving irregularly before 24 April 2018 would be deported (Fakhoury and Ozkul, 2019, pp. 26-28). “Voluntary” refugee returns have been estimated at 170,000. The EU and UNHCR warn against all return operations due to conditions in Syria but have no authority to intervene. During the autumn of 2022, Lebanon’s caretaker government announced plans to return thousands of refugees in breach of the country’s international obligations (HRW 2022).

2.3.6 Return and readmission policy

Lebanon has bilateral migrant readmission agreements with Romania (2002), Bulgaria (2002), Cyprus (2003), and Switzerland (2006) (UN-Habitat, 2018, p. 15). In the case of Lebanese-EU relations (explored in further detail below), Article 68 of the 2002 EU-Lebanon Association Agreement commits to readmitting nationals illegally present in each partners territory. The possibility of coordination and the development of readmission agreements is specified in Article 69 “if deemed necessary”. Lebanese authorities have been reluctant to allow Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon to return from other countries “if they do not have a residence permit in the country in which they currently stay” regardless of whether return is voluntary or by force as per a political decision by the Lebanese Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Emigrants (MII, 2020, p. 6).

3. International migration policy

relations

International factors related to migration to and from Lebanon include the large diaspora and involve substantial outward flows (see Part I). Additional aspects, includes flows of Palestinian refugees to the Gulf and Europe with sizeable diasporas (Doraï 2003, 2008). Lebanon as a transit country for migrants, as well as a source for emigrating Lebanese, determines its contemporary relationship with Europe and the development of the 2016 Compact (see further down). The economic, health, and political crisis ongoing since 2019 in Lebanon increased emigration, with grave implications for the Lebanese economy as younger professionals leave the country (Bendimerad, 2021).

3.1 Regional policy context

Lebanon is subject to few regional organisational policies related to migration. Regarding refugee flows in the Middle East, protection lies in the purview of the UNHCR (see Trad and Frangieh, 2007). Relevant regional entities dealing with migration include the League of Arab States which focuses on international migration and offers a framework for cooperation on the issue. The Population Policies, Expatriates and Migration department of the League of Arab States was formed in 2014 by merging two former entities. The focus of the department is skilled labour migration, “migrant women and their role in preserving the Arab identity of the migrating family as the base of the family”, and second and third generation Arab youths (Arab League, n.d., p. 8). The League also established the Arab Regional Consultative Process on Migration and Refugee Affairs (ARCP) and Foreign Ministers meet to discuss Migration and Expatriate Affairs (IOM, n.d.). A number of Arab League agreements relate to the issue of international migration and include:

- Arab Agreement No. 15 on Wage Determination and Protection, 1983

- Arab Charter on Human Rights, 2004

- Arab Declaration on International Migration, 2006

- Declaration of International Migration in the Arab Region, 2013 (listed in Arab League, n.d., p. 8)

Cooperation internationally includes the Working Group on International Migration in the Arab Region (est. 2014) which involves the attendance of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and 12 other UN agencies; the African-Arab Technical and Coordination Committee on Migration (est. 2013), as well as the UNHCR (see below) and European Union (EU) (see below).

3.1.1 UNHCR-Lebanon policy relations

Lebanon ratified neither the 1951 UN Refugee Convention nor its extension, the 1967 Protocol. This means that Lebanon does not have a national refugee law and its refugee policies are based on a 2003 Memorandum of Understanding (triggered by the Iraq invasion) that grants refugees temporary asylum under the patronage of the UNHCR (Janmyr, 2017). Consequently, asylum is time-limited and should be followed by resettlement. Owing to other international legal obligations, however, Lebanon is required to protect refugees from forcible return (non-refoulement). Contemporary policy relations between the Lebanese government and the UNHCR are determined by Syrian displacement. In 2011-2012, cooperation was hampered by tensions over which Lebanese ministry would manage the response. In parallel, interagency tensions within the UN and between the UN agencies and international NGOs, coloured coordination efforts (Mansour, 2017, pp. 10-13). A Crisis Cell was established by the incoming Lebanese government in February 2014, headed by the Ministry of Social Affairs. Meanwhile, several ministries wrote the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP) 2015-2016 (renewed every 12-18 months) in cooperation with around 100 other actors including INGOs and UN Agencies. Ultimately, the UNHCR came to be seen as one of the leading bodies but was unable to take charge due to intersectional mandates. Successive LCRPs have been underfunded and perceived as wish lists rather than enforceable policies with little monitoring and evaluation. In addition, the UNHCR remains caught between international refugee law and Lebanese policies on Syrian displacement (Janmyr, 2018).

3.1.2 EU-Lebanon migration policy relations

Lebanon and the EU have had a close political and economic relationship since the early 2000s and the EU is currently Lebanon’s largest trading partner with trade amounting to €7.7 billion in 2017 (Goulordava, 2019, p. 152). Lebanon’s relationship with Europe on the issue of migration policy began with individual countries in the 1960s, such as France, the former colonial power in Lebanon, as early as 1965 (Action Plan for EU-Lebanon Partnership, 2013-2015, p. 1). In 1977, a Cooperation Agreement was signed between Lebanon and the European Community (European Commission, 2011). The current framework for policy relations on migration is implemented under the umbrella framework of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which was established in 2004. The ENP consists of multiple bilateral agreements between the EU and surrounding non-EU states and is funded by the European Neighbourhood Instrument (European Community, 2006).[15] The ENP governs the relations between the EU and 16 ‘neighbourhood’ countries with the primary aim of “stabilisation” in the areas of politics, economy, and security (European Commission, n.d.). Developments in the Middle East after the popular uprisings in 2011 instigated a reform of the ENP framework in 2011, and in 2015 the EU published a Joint Communication reviewing the ENP and proposing reforms. This led to the system of identifying joint ‘priorities’ in collaboration with partner countries (see Action plan 2016-2020 below) (European Commission, 2015).

A study on Lebanese elite perceptions of the EU, highlighted that most were unaware of the legal frameworks guiding the EU-Lebanese relationship and considered that the EU was not an “active” player in Lebanon compared to the US (Goulordava, 2019, pp. 156-58). There was also a perception that relations were often guided by the policies of individual European states. Moreover, recent EU policies towards Syrian refugees hardened the perception of ‘Fortress Europe’ (Goulordava, 2019, pp. 159, 164 and 166).

EU-Lebanon Association Agreement (AA)

The ENP in Lebanon was negotiated in the form of the EU-Lebanon Association Agreement (AA) and is the only legally binding document that governs migration between the EU and Lebanon. It was agreed in January 2002 and entered into force on April 6, 2006.[16] The three negotiated EU-Lebanon Action Plans (2007-2011; 2013-2015; 2016-2020) are more flexible and represent an institutional framework for dialogue on migration that takes place between the Association Council of the European Union and Lebanon.[17] The implementation of Action Plans has been hampered since 2007 by frequent incidents of internal strife in Lebanon. For instance, the 2010 implementation report of the 2007 Action plan notes the inability to pass laws essential to the ENP Action Plan due to the political fall-out from the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005 and the subsequent UN inquiry into the murder (Special Tribunal for Lebanon) (European Commission, 2011).

The 2007 action plan highlighted the limited influence of the EU, evidenced by the fact that Palestinians were not defined as a refugee population. Indeed, reviews of the ENI and the EU-Lebanon Action plans between 2006-2010 show that migration issues were not a policy priority (European Commission, 2011). The 2009 assessment of the ENI reported the beginning of infrastructural improvements at the Masnaa border post, seaports, and the airport, but highlights an overall “lack of an overarching Integrated Border Management strategy” as well as lack of information sharing with the EU (European Commission, 2010, p. 11).

EU-Lebanon Action Plans (2007-2020)

The nature of the policy relationship on migration shifted with the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011 and the increase in irregular migration to Europe via sea and land routes which peaked in 2015. The shift was catalysed by the unmanageability of migration flows from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. This pushed the EU to engage in more “informal, local and pragmatic decisions” rather than “legally binding and formal cooperation”, a pathway chosen due to resistance from MENA states and for the EU to ensure continued cooperation with Southern neighbours (Seeberg and Zardo, 2020, p. 2).

In this context, Lebanon as a transit country was re-framed as a bulwark against irregular migration into Europe and the EU became one of the main funding bodies in Lebanon. The approach was justified as part of “a broader resilience-building paradigm” (Fakhoury, 2020, p. 6). As argued by multiple authors, the intervention after 2015 “offer[ed] avenues to outsource migration control and to prevent onward migration by offering refugees the solutions of self-reliance and resilience” in the countries of reception (Fakhoury, 2020, p. 7). Of the €24.9 billion mobilized by the EU to address Syrian displacement since 2011, €2.4 billion went to Lebanon (European Commission, 2016a). The European Commission reported that this sum included €670.3 million in bilateral assistance under the ENI, €933 million in resilience assistance through the EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis (est. 2015), and €666 million in humanitarian aid. Finally, €61 million was dispensed through two mechanisms: the Instrument Contributing to Stability and Peace, and the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (Ibid.). An additional €402.3 million was granted to Lebanon with a focus on the following areas:

(1) economic growth and job creation;

(2) local governance and socio-economic development; and

(3) rule of law and enhancing security between 2014-2020.

Migration in the 2007-2011 Action Plan: Article 19 provides for establishing a dialogue on migration including asylum, mobility, illegal migration, return and visas. Under each section of the action plan, there are a number of priorities: information exchange and analysis of migration patterns; the inclusion of Lebanon in existing EU cooperation structures on migration;[18] dialogue on existing migration, integration and mobility policies; the possibility of negotiating a readmission agreement; cooperation on travel documents; improved short-term visas; the inclusion of stateless and Palestinians in relation to travel documents and asylum; enhancing inter-agency border management, including initiating cooperation between Lebanese authorities and FRONTEX; and dialogue on implementing the UN Convention against Trans-national Organized Crime (European Community, 2006).

Migration in the 2013-2015 Action Plan: Priorities for the plan included the protection of vulnerable populations including Palestinians (Action Plan for EU-Lebanon Partnership and Cooperation 2013-2015, p. 2.). Migration issues included setting the mandate for the Joint EU-Lebanon sub-committee on social and migration issues. The sub-committee prioritizes the empowerment of municipalities and enhancing social protection, but also cooperates on migration issues through dialogue and information exchange. Areas of cooperation in the sub-committee include migration management; prevention and control of illegal migration (including monitoring and return); readmission; travel documents and visas; and synergies on existing initiatives on migration research (Sec. 3.2. in Annex II Further Objectives, Action Plan, 2013-2015).

Migration in the 2016-2020 Action Plan: is made up of two sections: the EU-Lebanon Partnership Priorities, and the Lebanon Compact.

(1) the EU-Lebanon Partnership Priorities is framed in the context of mass displacement of Syrians after 2011. Migration is noted as one of the “most urgent challenges” and the document emphasizes the joint policy of both parties to urge “safe return [of Syrians] to their country of origin,” while “being mindful [of] the imperative of building conditions for the safe return of refugees from Syria and displaced Syrians […] in accordance with all norms of international humanitarian law and taking into account the interests of host countries” (Republic of Lebanon, 2016, p. 4). The priorities also note that “the EU [acknowledges] that support for Syrian refugees cannot be done outside the framework of supporting the Lebanese national economy and investing in infrastructure and productive projects,” thus cementing development aid as the primary modality (Ibid.). As explained by the European Commission communication framing the Priority strategies, in return for the aid, the Lebanese government “should make efforts on the social and economic inclusion of Syrian refugees in order to improve their living conditions and legal residence strategies” (European Commission, 2016b, pp. 13-14).

The Priorities did not touch on secondary migration from Lebanon, although there is the explicit understanding that the 2016 Compact acts as a means of compensation to Lebanon to mitigate such migration flows.[19] Nonetheless, the section on mobility and migration highlighted the need to 1) negotiate a joint declaration launching a mobility partnership, and 2) strengthen cooperation on migration through the Lebanon-EU mobility partnership, which sought to build capacity in terms of regular and irregular migration. Discussions on the mobility partnership began in 2015 but remained on a technical level until 2018 (European Commission, 2018, p. 11).

(2) The Lebanon Compact builds on the Priorities and aimed at operationalizing the improvement of living conditions among Syrians including a comprehensive aid package.[20] The Lebanon Compact utilized multiple existing EU policy frameworks including the EU Trust Fund for Syria through which €400 million was pledged to Lebanon in 2016-2017. The initiative was negotiated in parallel with the Jordan Compact and at the time offered a new means of identifying commitments and solutions to the challenge of Syrian refugees in Lebanon (Fakhoury, 2020, p. 7). There are three central factors in understanding the emergence of the Lebanon Compact:

- The Compact emerged out of the February 2016 London Conference on ‘supporting Syria and the region’ as part of a larger framework of compacts, meaning the Lebanon Compact was not negotiated within established channels of the ENP. Rather the design and negotiation process took place in a wider global context with broader participation which both the EU and Lebanon mobilized to increase international support for the arrangement (Seeberg and Zardo, 2020, p. 10).

- Within Lebanon, the compact was negotiated during heightened political uncertainty stemming from the Syrian war, where the Lebanese political party Hezbollah intervened on the side of the Syrian government in 2013 (Seeberg, 2018, p. 3). The EU, as a means of providing counterweight to Hezbollah’s influence, continued their decades long support for the Lebanese Army. In this context, the Lebanon Compact can be read as a continuation of aid aimed at ‘stabilizing’ and balancing state/non-state relations in the country by addressing the security and counterterrorism sectors in addition to economic growth, job creation, governance, rule of law, and education (Fakhoury, 2020, pp. 8, 11; Seeberg, 2017, p. 3).

- The utilisation of the Lebanon Compact as a migration tool, as with the Jordan Compact, was rooted in the need for informal mechanisms to secure results and ensure continued dialogue between the EU and third countries such as Lebanon (Seeberg and Zardo, 2020). Critics of the Lebanon Compact regularly highlight the lack of enforcement mechanism and tangible requirements and deliverables. Unlike in Jordan, the Lebanon Compact is stated to provide for the social and economic inclusion of Syrians. However, the Compact does not provide for their formal employment, hence the agreement is more often conceptualized as a ‘declaration of intent’. Yet, the Compact was negotiated within a larger marketplace of aid where both the EU and Lebanon were keen to come to an agreement, despite negotiating at a time when few other areas had seen any substantial development. The lack of targets and ‘informalisation’ of the agreement was seen as a means of ensuring at least partial implementation that would not be delayed by the formal requirements and technical negotiations necessary for any formal agreement (Seeberg and Zardo, 2020; Fakhoury, 2020, p. 9).

It is also important to note that the Lebanon Compact, and its lack of implementation, resulted from the framing of the agreement through the EU’s 2015 crisis narrative that failed to take into account domestic political fragmentation in Lebanon and predominantly framed the Syrian influx in terms of security and instability. Moreover, the call for greater integration of Syrians into the Lebanese economy outlined by the Compact, took place at a time when Lebanese government was increasing labour and residency restrictions on Syrians (with a few exceptions) (Fakhoury, 2021), thereby ensuring that the intervention could not offer more than temporary and half-hearted solutions (Fakhoury, 2020, pp. 8-11). In 2020, negotiations continued under the New Pact and Agenda.

3.1.3 A New Pact and Agenda? The New Pact on Migration and Asylum and the New Agenda for the Mediterranean

The New Agenda for the Mediterranean was launched in February 2021 and consists of communication and a working paper on the Economic and Investment Plan for Southern Neighbours. ‘Migration and mobility’ is the fourth pillar of the agenda and are financed by the re-tooled ENI known as the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) that promises €7 billion between 2021-2027.[21] Although written into the sustainable development programmes for 2030, including the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement, the inclusion of the migration policy in the New Agenda is a continuation of previous policies and drafted in line with the Pact on Migration and Asylum that entered into force in September 2020 (ANND, 2021). Other aspects are also continued from previous policies, such as the tailor-made approaches to individual partner states; targeted assistance to help partner countries support migrants; the adoption of the Voluntary Return and Reintegration Strategy to combat irregular migration; furthering regional cooperation within existing frameworks; and encouraging legal migration through resettlement programmes and labour mobility schemes (European Commission, 2021a, pp. 16-18). In 2021, the EU promised a four-year aid package of €2.2 billion to Lebanon, in addition to Iraq, Jordan and Syria (European Commission, 2021b, p. 17). The New Pact on Migration and Asylum aims to standardize asylum procedures across the EU and amend the 2016 Asylum Procedure Regulation by integrating the policies of screening, asylum and return into one legislative package. However, the reform has been criticised for its introduction of pre-screening at external borders of the EU allowing authorities to fast-track either asylum or return procedures at the port of disembarkation (Guibert, Milova and Movileanu, 2021, pp. 1-2).

Meanwhile, the EU also renewed the EU Action Plan against Migrant Smuggling for 2021-2025, that will institute tailored approaches with Southern partner countries. As noted by two different NGO networks, this means that despite a promise to address the root causes of migration, the New Agenda continues its focus on “externalization, deterrence, containment and return” and aims to keep migrants away from European borders (ANND, 2021). Indeed, the resilience policies encompassed in the Lebanon Compact were replaced by renewed calls for refugee returns as the most durable solution. At the Brussels Conference hosted in May 2022, the EU repeated calls for the return of Syrian refugees while Lebanon formally announced to the UNHCR that it no longer had the capacity of being a refugee host state (Fakhoury and Stel, 2022). As noted by Tamirace Fakhoury and Nora Stel (2022), the EU’s resilience policies contradict Lebanese policies pushing for return risk “contributing to refugee precarity rather than dealing systematically with root causes inducing returns”.

3.1.4 Relations between EU migration policy and Lebanese migration policy

According to Tamirace Fakhoury (2020, p. 2) the EU’s logic of refugee governance in Lebanon is marked by three interrelated aspects:

- “reinforced cooperation with the government;”

- “emphasis on resilience-building despite the political elites’ contestation of such an approach;”

- “a tactical non-engagement towards Lebanon’s securitised refugee practices.”

This is a good place to begin unpacking the logic of EU migration policy and its impact on Lebanon, beyond mobility agreements. Since the Association Agreement was first signed in 2002 and implemented in 2006, the policy issue of ‘migration’ developed into a pillar in EU-Lebanese diplomacy and cooperation. This is particularly evident in policy developments after 2012 when the EU sought engagement with Lebanon as a key partner in managing migration from a distance.

The policy shift was accompanied by an enormous influx of funds as well as the creation of dedicated financial tools under the EU Trust Fund for Syria (Madad Fund). However, EU efforts clashed with domestic political aims that hamper the integration of Syrians into Lebanese society and the economy. Indeed, the annual Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees (VASYR) surveys between 2013-2020 highlight the trend of dispossession after 2014 as Syrians became progressively vulnerable. As Lebanon suffered from progressive shocks after 2019 – the COVID-19 pandemic, political crisis, the Beirut Blast, and the financial crisis – each incident served to highlight how European efforts to first ‘stabilize’ and later ‘strengthen resilience’ had failed. The non-binding nature of EU-Lebanese cooperation may have inspired greater debate on the protection of migrants around 2015 but fell short in providing for their protection en masse. Moreover, the EU’s practices clashed with its own values emphasising the protection of migrants, whereby undermining their soft power appeal (Goulordava, 2019).

A key aspect to highlight is that EU policy mostly ignored the endemic corruption, fragmentation, and mismanagement within the Lebanese political system. Research is nascent, but preliminary interviews highlight some of the impacts of EU and international funding on the Lebanese political system which ranks as one of the most corrupt in the world with a corruption perception index (CPI) rank of 154 of 180 countries polled.

One UN employee noted the strengthening of particular units within governmental bodies such as the line ministries that occurs when international actors seek Lebanese partners and provide a boost in dedicated funding to a particular branch or office. This occurs at the expense of organisation coherence and the impact is that these units are able to offer substantially larger wages (compared to the rest of body). (author’s interview, UN official, July 2019). Overall, as noted by Fakhoury (2020, p. 5), EU policy choices were largely disconnected from events unfolding on the ground and was used to uphold the political elite rather than improve every-day lives. This trend has largely continued with the reformulation of the latest 2020 Pact and 2021 Agenda.

4. Conclusion

The main features of EU-Lebanese migration policy relations have been analyzed, but policy impacts and priority changes over the past 15 years should be studied further. There are four areas that would benefit from further analysis: the EU’s resilience approach vis-a-vis Lebanon; the wider impact of EU funding in Lebanon; understanding migration policy relations with non-EU states; and contemporary migration dynamics after the economic crisis in 2019.

The first relates to the EU’s migration policy framework combining resilience and stabilization, especially as Lebanon is wary of resilience which signals a continuation of its host state role. The failure of the EU’s resilience framework to safeguard refugee rights and dignified returns has been attributed to Lebanon’s fractured political environment and economic malaise.

Second, the EU’s massive funding not only only impacts Lebanon’s migration governance, but also the country’s public policy and civil society sectors. This wider impact of this on migration aspirations and EU externalization policy are less well understood, especially in the context of the country’s economic and political crisis.

While the EU is a major donor to Lebanon, it is one among many that may have either complementary or competing policy aims. As highlighted in this report, the EU is only one migration destination (framed through the lens of irregular migration in particular), but what are the policies for the other main migration destinations such as the Gulf states and North America?

The final aspect relates to migration in light of the economic downturn post-2019. There are at least two intertwined factors here, the first is the mass exodus of Lebanese citizens. A recent Gallup poll finds that 63 % of the Lebanese population want to leave the country permanently. This is the highest figure recorded from any country polled since 2005, and more than double the highest figures polled in Lebanon during the past decade (Gallup, 2021). As highlighted in the 2022 parliamentary elections, the diaspora is likely to have a considerable impact on domestic politics and the economy reliant on remittances. How then, will the Lebanese state engage with its diaspora? The second aspect is the plan to facilitate the voluntary return of Syrians from Lebanon since adopting the National Return Plan in 2020. How will this impact the country’s international commitment to “non-refoulment” in a situation where Lebanon pursues what has been termed a “soft deportation” of Syrian refugees.

References

Abu-Rish, Ziad (2016) ‘Municipal Politics in Lebanon’, MERIP 46, Fall, no. 280. Available at: https://merip.org/2016/10/municipal-politics-in-lebanon/.

Action Plan for EU-Lebanon Partnership and Cooperation 2013-2015. Available at: https://www.localiban.org/IMG/pdf/action_plan_ue-lebanon_2013-2015.pdf.

AlKantar, Bassem (2016) ‘Lebanese Diaspora: The Imagined Communities – History and Numbers.’ Libc.net, July 30. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20200920010756/ https://libc.net/2016/07/30/lebanese-diaspora-the-imagined-communities-history-and-numbers/.

Ajluni, Salem., and Mary Kawar (2015) Towards Decent Work in Lebanon: Issues and Challenges in Light of the Syrian Refugee Crisis. (Report). Kuwait: International Labour Migration, Regional Office for Arab States.

ANND (Arab NGO Network for Development) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (2020) ‘Joint Statement’, 6 October. Available at: https://ecre.org/the-pact-on-migration-and-asylum-to-provide-a-fresh-start-and-avoid-past-mistakes-risky-elements-need-to-be-addressed-and-positive-aspects-need-to-be-expanded/.

ANND (2021) ‘The ANND position on the New Agenda for the Mediterranean’. Available at: https://www.annd.org/uploads/publications/ANND_position_on_EU_Communication.pdf.

Arab League (n.d.) ‘International Migration in the Arab region’. Presentation by the Population Policies, Expatriates and Migration Department of the Arab League, p. 8. Available at: https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/ICP/RCP/2015/2015-Global-RCP-League-of-Arab-States-Presentation.pdf.

Audebert, Cédric., and Doraï, Muhammad K (eds.) (2010) Migration in a Globalised World: New Research Issues and Prospects. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Azzi, Aline (2021) ‘Lebanon Ranked 12th Worldwide in Remittances Received per GDP,’ Blom Bank Group, The Research Blog [blog], September 6. Available at: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/41452/lebanon-ranked-12th-worldwide-in-remittance-received-per-gdp/.

Bendimerad, Rym (2021) ‘Lebanese students abroad fight for their future’, Al-Jazeera, 27 April. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/4/27/lebanese-students-abroad-fight-for-their-future-2.

Bulloch, John (1977) Death of a Country: The Civil War in Lebanon. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Chaaban, Jad., Ali Chalak, Tala Ismail and Salma Khedr (2018) Analysing Migration Policy Frames of Lebanese Civil Society Organisations. ((MED)RESET Working Paper, No. 19). Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali. Available at: https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/analysing-migration-policy-frames-lebanese-civil-society-organizations.

Chaar, Hani (2021) Protecting domestic workers in Lebanon: How to amend the labour code to better protect domestic migrant workers in Lebanon?. (Briefing paper). Geneva: International Labour Organisation. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_776383.pdf.

Chaccour, Christopher (2022) ‘Lebanon’s Minister of the Displaced just announced plan to send Syrians refugees back home’, The 961, July 4. Available at: https://www.the961.com/minister-plan-to-send-back-syrian-refugees/.

Chalcraft, John T (2008) The Invisible Cage: Syrian Migrant Workers in Lebanon. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

CIA (2021) Lebanon Profile. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/lebanon/.

Dagher, Georgia (2022) The Lebanese Diaspora and the Upcoming Elections: Lessons from the 2018 voting. (ARI Research Paper). Paris: Arab Reform Initiative. Available at: https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/storage.arab-reform.net/ari/2022/05/02145721/2022_05_02_ARI_Research_Paper_Election2018_final-2.pdf.

Dagher, Jonathan (2020) ‘Trapped in Lebanon: Sudanese Migrants desperate to find a way home.’ Middle East Eye, 25 September. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/lebanon-sudan-migrant-workers-beirut-return-home.

De Bel-Air, Françoise (2017) Migration Profile: Lebanon. (Report 17/2017). Florence: EUI. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/46504/RSCAS_PB_2017_12_MPC.pdf.

Di Bartolomeo, Anna., Fakhoury, Tamirace., and Perrin, Delphine (2010) Lebanon. (CARIM – Migration Profile). Fiesole: European University Institute. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/22437/Lebanon%20migration%20profile%20EN%20with%20links.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Diab, Jasmin Lillian., and Saban, Aslı (2022) ‘The Dom in Lebanon: Citizens, Migrants, Refugees and Nomads’, February 7. Available at: https://soas.lau.edu.lb/news/2022/02/the-dom-in-lebanon-citizens-migrants-refugees-and-nomads.php.

Doraï, M. K. (2003). "Palestinian Emigration from Lebanon to Northern Europe: Refugees, Networks, and Transnational Practices." Refuge 21(2): 23-31.

Doraï, Muhammad K (2008) ‘Itineraries of Palestinian refugees: Kinship as resource in emigration’, pp. 85-104. In Hanafi, S. (ed.) Crossing Borders, Shifting Boundaries. Palestinian Dilemmas. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Euro-Mediterranean Agreement establishing an Association between the European Community and Lebanon (2006). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52006PC0365:EN:HTML.

European Committee of the Regions (n.d.) Lebanon – Immigration and Asylum. Available at: https://portal.cor.europa.eu/divisionpowers/Pages/Lebanon-Immigration-and-asylum.aspx.

European Commission (n.d.) European Neighbourhood Policy: What is it?. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/european-neighbourhood-policy_en.

European Commission (2010) Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the communication from the commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Taking Stock of the European Neighbourhood Policy. Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in 2009: Progress Report Lebanon. (SEC/2010/0525 final). Available at: https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1350078/1226_1275377717_sec10-522-en.pdf.

European Commission (2011) Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in 2010. Country Report: Lebanon. (SEC/2011/0637 final). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52011SC0637&from=EN.

European Commission (2015) Review of the European Neighbourhood Policy. (JOIN(2015) 50 Final), 18 November. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/document/download/6d6a2908-9d79-42ad-84ae-9122d0f863a3_en.

European Commission (2016a) Lebanon. Available via Wayback Machine at: https://web.archive.org/web/20210109223457/https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/neighbourhood/countries/lebanon_en.

European Commission (2016b) On Establishing a new Partnership Framework with third countries under the European Agenda on Migration. (Communication COM(2016) 385 Final). 7 June. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:763f0d11-2d86-11e6-b497-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

European Commission (2018) High Representatives of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Joint Staff Working Document: Report on the EU-Lebanon relations in the framework of the revised ENP (2017-2018). (SWD(2018) 484 final). 29 November. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018SC0012&from=ES.

European Commission (2021a) Joint Communication: Renewed partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood – A New Agenda for the Mediterranean. (JOIN(COM(2021)2)). 9 February. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/joint_communication_renewed_partnership_southern_neighbourhood.pdf.

European Commission (2021b) Report on Migration and Asylum. (COM(2021) 590). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/report-migration-asylum.pdf.

European Community (2006) Proposal for a Council Decision on the position to be adopted by the European Community and its Member States within the Association Council established by the Euro-Mediterranean Agreement establishing an association between the European Community and its Member States, of the one part, and the Republic of Lebanon, of the other part, with regard to the adoption of a Recommendation on the implementation of the EU-Lebanon Action Plan. (COM/2006/0365 final). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52006PC0365:EN:HTML.

European Union (n.d.) The EU and Neighbours: Evolving Relations. Available at: https://www.euneighbours.eu/en/policy/european-neighbourhood-instrument-eni.

Fakhoury, Tamirace (2018) Lebanese Communities Abroad: Feeding and Fueling conflicts. (Research Paper). Paris: Arab Reform Initiative, 5 December. Available at: https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/lebanese-communities-abroad-feeding-and-fuelling-conflicts/.

Fakhoury, Tamirace (2020) Lebanon as a Test Case for the EU’s logic of Governmentality in Refugee Challenges. (IAI Commentaries 94). Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali. Available at: https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/lebanon-test-case-eus-logic-governmentality-refugee-challenges.

Fakhoury, Tamirace (2021) ‘Reflections on the EU’s external refugee governance approach in Lebanon,’ (pp. 16-19) in EuroMedMig (ed.) The New EU Pacts and its impact on Mediterranean Migration Governance: Continuity or rupture? (EuroMedMig Policy Paper Series no. 3). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Available at: https://repositori.upf.edu/bitstream/handle/10230/46211/EU%20pact_Euromedmig%20Policy%20Paper_2021_Jan.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y.

Fakhoury, Tamirace., and Ozkul, Derya (2019) ‘Syrian refugees' return from Lebanon.’ Forced Migration Review, pp. 26-28.

Fakhoury, Tamirace., and Stel, Nora (2022) ‘Reconsidering Resilience: The EU and Premature Refugee Returns in Lebanon’, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, June 16. Available at: https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/articles/details/4694/reconsidering-resilience-the-eu-and-premature-refugee-returns-in-lebanon

Fawaz, Mona., and Isabel Peillen (2003). Urban Slums Reports: The case of Beirut, Lebanon. London: U. N. Habitat and Earthscan.

FCDO (UK) (2022) Foreign Travel Advice: Lebanon. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/lebanon/entry-requirements.

Forster, Robert (2022) Building back better: The politicization of disaster and displacement response architecture in Lebanon. (NCHS Report). Bergen: Norwegian Center for Humanitarian Studies.

Gallup (2021) Leaving Lebanon: Crisis Has Most People Looking for Exit. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/357743/leaving-lebanon-crisis-people-looking-exit.aspx.

General Security (n.d.) The List of countries that have the right to a Lebanese visa. Available at: https://www.general-security.gov.lb/en/posts/38.

Ghandour, Hind (2018) ‘A Space for Identity: The case of Lebanon’s Naturalised Palestinians’ (pp. 91-106) in Agius, C. and Keep, D. (eds.) The Politics of Identity: Place, Space and Discourse. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Goulordava, Karina (2019) ‘Lebanese Elite’s Views on Lebanon and its relations with the EU’ (pp. 147-169). In Görgülü, A., Kahyaoğlu, G. D., and Kamel, L. (eds.) The Remaking of the Euro-Mediterranean Vision: Challenging Eurocentrism and Local Perceptions in the Middle East and North Africa (Vol. 2). Bern: Peter Lang.

Guibert, Lucie., and Maria Milova, Daniela Movileanu (2021) The New Pact on Migration and Asylum: A brief summary and next steps. (Report). Brussels and Bruges: 89 Initiative.

Hager, Anselm (2021). What Drives Migration to Europe? Survey Experimental Evidence from Lebanon. International Migration Review, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 929-950.

Hajj, Nadya (2016) Protection Amid Chaos: The Creation of Property Rights in Palestinian Refugee Camps. New York: Columbia University Press.

Halabi, Zeina (2004) Exclusion and identity in Lebanon’s Palestinian Refugee camps: a story of sustained conflict, Environment and Urbanisation, vol. 16, no. 2, October, pp. 39-48.

Hourani, Albert., and Nadim Shehadi (1992) The Lebanese in the World: A Century of Emigration. London: The Centre for Lebanese Studies and I.B. Tauris.

Hourani, Guita (2007) Lebanese Diaspora and Homeland Relations. Conference on Migration and Refugee Movements in the Middle East and North Africa’. University of Cairo, Egypt, October 23-25, 2007. Available at: https://documents.aucegypt.edu/Docs/GAPP/Guitahourani.pdf.

HRW (2018) Lebanon: Discriminatory Nationality Law. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/10/03/lebanon-discriminatory-nationality-law.

HRW (2020) Lebanon: Blow to Migrant Domestic Worker Rights. October 30. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/30/lebanon-blow-migrant-domestic-worker-rights.

HRW. 2022. Forced Return of Syrians by Lebanon: Unsafe and Unlawful, 6 July 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/07/06/forced-return-syrians-lebanon-unsafe-and-unlawful