EFFEXT Background Papers – National and international migration policy in Ghana

Part I: National migration policies

Past and current migration dynamics

Migration governance structure

National Labour Migration Policy

Part II: International migration policy relations

AU: Migration governance frameworks and the ‘Free Movement Protocol’

ECOWAS: The ‘Free Movement Protocol’ and the ‘Common Approach to Migration’

Europe-Ghana relations on migration

Collaboration on free regional movement

Collaboration on the development of national policies

Collaboration to limit irregular migration

About the EFFEXT Background Papers

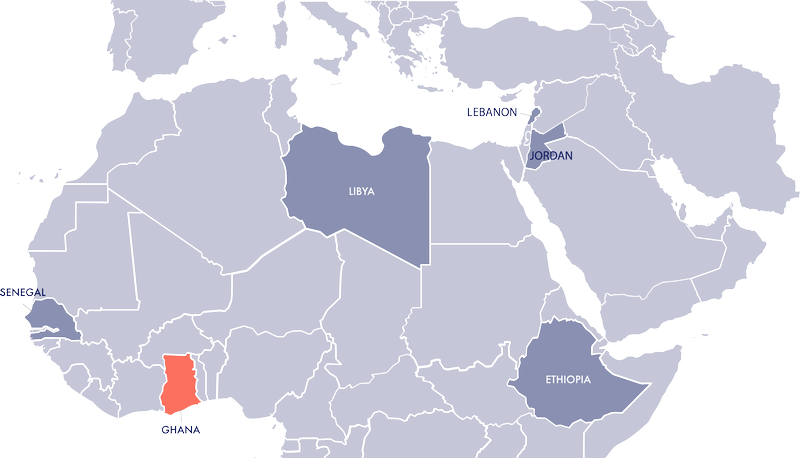

The Effects of Externalisation: EU Migration Management in Africa and the Middle East (EFFEXT) project examines the effects of the EU’s external migration management policies by zooming in on six countries: Jordan, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Senegal, Ghana and Libya. The countries represent origin, transit, and destination countries for mixed migration flows, and differ in terms of governance practices, state capacities, colonial histories, economic development and migration contexts. Bringing together scholars working on different case countries and aspects of the migration policy puzzle, the EFFEXT project explores the broader landscape of migration policy in Africa and the Middle East.

The EFFEXT Background Papers guide the fieldwork, case selection and analysis of migration policy effects in the EFFEXT project’s case countries. The papers are based on desk-reviews of scientific literature and grey literature, the latter including government documents, governmental and non-governmental reports, white papers and working papers.

This EFFEXT Background Paper provides a brief presentation of migration and migration policy dynamics in Ghana. It presents an overview of key national and international migration policies, and outlines the key migration governance structures in Ghana. In terms of international relations, the paper primarily focuses on regional and European collaboration. The Background Paper concludes with a short summary of the trends in Ghana’s collaboration with European actors, and reflects on key questions that need to be explored when studying the impact of European migration management in Ghana.

Two of the paper’s co-authors, Leander Kandilige and Joseph Teye, have been involved as consultants in many of the policy development processes described in the paper, such as in the making of the Diaspora Engagement Policy and the National Labour Migration Policy, and in several smaller policy initiatives funded by European donors. The paper, therefore, includes their professional insights on policy processes and challenges in Ghana’s migration governance.

Part I: National migration policies

Introduction

In Ghana, policy priorities on migration are linked to the mixed and multi-directional migration flows, spanning from labour-induced mobility to forced displacement. The country’s porous borders make it difficult to accurately record migration flows, and as a result official statistics on migration stocks and flows vary (Awumbila et al., 2014). Yet, recent figures illustrate that Ghana is a major destination and origin country of both regular and irregular migrants. According to UN DESA, the Ghanaian emigrant stock soared from approximately 762 000 in 2010, to 1 004 000 in 2020 – of which 466 000 live in other West African countries. Over the same decade, the number of immigrants in Ghana, primarily originating from the region, rose from about 194 000 to 476 000 (UN DESA, 2021). In terms of flows, the latest statistics from Ghana Immigration Service (GIS) shows that as many as 956 000 people were registered at entry in 2018 alone (GIS 2019).

This background paper seeks to map the current migration governance structure in Ghana, and relevant national and international policies on migration. Given the multifaceted migration flows to and from Ghana, the background paper first introduces past and current migration dynamics, focusing primarily on emigration flows. This serves as a backdrop for the ensuing part of the paper, which introduces Ghana’s national migration governance, national migration policies, regional collaboration on migration governance in West Africa, and finally, collaboration with European stakeholders on migration. The paper excludes policy shifts in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic as it seeks to highlight long-term trends. It should be noted, however, that Ghana closed its borders in March 2020 as a response to the pandemic, and re-opened the borders in September 2020. The border closures impeded both migration and cross-border trade in the region. In addition, recent progress in the area of migration governance was derailed, creating new challenges for migration management and an increased need for local cooperation on migration (Le Coz and Hooper, 2021).

Past and current migration dynamics

Historically, migration and other forms of human mobility have been central to development in Ghana. The role of migration in the formation of the country is well documented (see e.g. Beals & Menezes, 1970; Boahen, 1966, 1970, 1975; IOM, 2020a). In the pre-colonial era, Ghanaians moved to other African regions for trade, security, and in search of fertile farmlands (Peil, 1995; Adepoju, 2003). At the same time, economic affluence and high demand for labour made Ghana an important destination country for immigrants from West Africa (Anarfi, 1982; Anarfi et al., 2003; Awumbila et al., 2008; Quartey, 2009). During the nineteenth century, the colonial era, Ghana became a net receiver of migrants who came to work on the cocoa plantations and in the mines.

Box 1: Where do the migrants to Ghana come from?

- The number of international migrants rose from 191 601 in 2000 to 476 412 in 2020 (UN DESA 2021).

- 399 000 originated in Western Africa

- 2700 from Asia

- 2600 from Europe

- 1000 from North America

- Yet, more than 956 000 people were registered at entry points to Ghana in 2018, including returning Ghanaians (30%), Nigerians (7%), Americans (8%), and British Nationals (5%) (GIS 2019).

After independence in 1957, Ghana’s political priorities were influenced by Pan-Africanism which encouraged immigration, even from beyond the African continent (Anarfi & Awusabo-Asare, 2000). Yet, internally, rural-urban migration continued to dominate – as it had in the past – and north-south migration increased in relation to the economic and development gap between Ghana’s ‘two halves’ after independence (Abdulai, 1999; Nabila, 1986; Johnson, 1974, Awumbila et al., 2015; GSS, 2013; Teye, Awumbila & Darkwah, 2017). The few instances of international emigration in the immediate post-independence period predominantly involved students and other professionals whose services were required within the African continent.

Source: Illustration by IOM 2019, based on data by UN DESA 2019.

However, with the decline of the Ghanaian economy from the 1960s to 1980s, migration patterns changed towards an increase in labour emigration (Anarfi et al., 2010; Asiedu, 2010). Professionals began to leave Ghana in droves from the late 1970s due to poor climatic conditions (leading to drought and famine) and a further economic downturn. Harsher economic restrictions were imposed on the country from the mid-1980s and led to mass-movement – or ‘brain-drain’ of medical practitioners, pharmacists, teachers, nurses, and engineers (Asiedu, 2010; SIHMA, 2014).

From the late 1990s to 2000s, the Ghanaian economy experienced a steady growth. A good number of Ghanaians continued to migrate, which may be explained in part by people’s increased ability to afford the cost of international migration, as well as the existence of established social networks which facilitated the movement (UN DESA, 2015; Bruni et al., 2017). In relation to forced movement, the 1990s were marked by political upheavals in the region which led to an influx of refugees from Liberia, Togo, Cote d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone (Agblorti, 2011; Essuman-Johnson, 2003; Quartey, 2009). In response, the Ghana Refugee Law was created in 1992 and through the assistance of UNHCR, the Ghana Refugee Board was established soon after (Essuman-Johnson, 2003; Ghana Refugee Board, 2017). As of 2008, Ghana was the fourth-largest host of refugees and asylum seekers in the West African sub-region (Ghana Refugee Board, 2017; UNHCR, 2009), though it also hosts refugees and asylum seekers from other African countries (Agblorti, 2011). According to the Ghana Refugee Board (2022), Ghana currently hosts 13 334 refugees in four main refugee camps and as urban refugees in Accra.

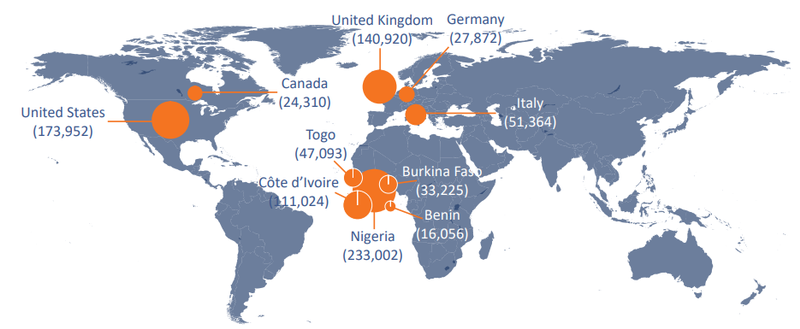

Although media narratives tend to portray an exodus of migrants from Africa to Europe, figures show that Ghanaian emigration patterns are highly diverse. According to UN DESA (2019) close to 50 per cent of the Ghanaian emigrant population reside in other African countries – primarily in the West African region. Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire are the top two destinations, with approximate stocks of 233 000 and 111 000 Ghanaian migrants respectively. Historically and currently, Ghanaians also migrate irregularly beyond the region, for example, to Libya where the IOM recently identified approximately 22 000 Ghanaians (IOM, 2020a). Yet, Ghanaians also migrate beyond Africa, and mainly to Europe, USA and Canada. In 2019, approximately 283 000 Ghanaians resided in Europe, 198 000 in North America, and 9 600 in Asia and Oceania combined (UN DESA, 2019).

A particular interesting south-south migration corridor is the increase in Ghanaian domestic workers travelling to the Middle East (Kandilige et al., 2019; Awumbila, et al., 2019). While this flow has been limited by policy since 2017, when a ban on visa provision for domestic workers (‘Visa 20’) was implemented due to reports of human rights abuses (Kandilige et al., 2022), the flow has steadily increased. Figures provided by the Ghana Labour Department show that private agencies recruited 2372 workers to the region in 2016 (Awumbila et al., 2019), and up to 1589 workers from January to May 2017. The actual numbers of migrant domestic workers are likely to be higher as these figures exclude workers who migrate individually (Kandilige et al., 2019).

Migration governance structure

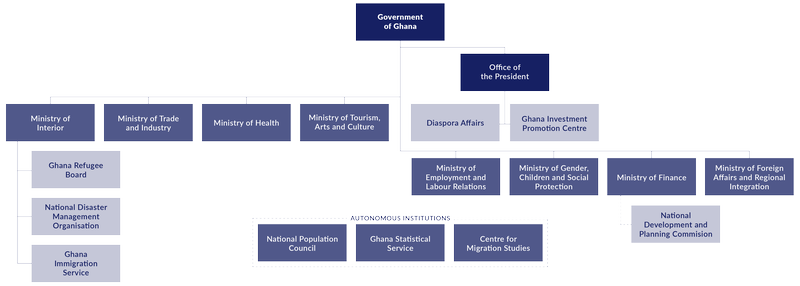

Ghana’s migration governance structure is complex. There is no overarching agency mandated to coordinate all migration-related activities in Ghana, and different government ministries, departments and agencies are tasked with formulating policies and managing different aspects of migration-related issues. This is in spite of the fact that the National Migration Policy of Ghana recommended the establishment of a Ghana National Commission on Migration (to coordinate all migration-related issues in the country), which is yet to be established seven years after the launch of that policy. While more actors are involved, the key actors include eight ministries, three sub-ministerial bodies, two offices at the Presidency and three autonomous institutions (see Figure 2 for an illustration). The paper’s appendices include overviews of all stakeholders involved in Ghana’s migration governance, with a summary description of their roles, in 2022 (Appendix 1) and 2014 (Appendix 2).

Source: Illustration by IOM 2019, based on data by UN DESA 2019.

Political parties in Ghana, especially the two main political parties the ‘National Democratic Congress’ (NDC) and the ‘New Patriotic Party’ (NPP), are also important actors shaping migration governance in Ghana. These two parties have played strategic roles guiding the current migration policy landscape, and the bi-partisan approach may have allowed for broad ownership of the recent policy processes. Similarly, through a whole-of-society approach, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO)s and other non-state actors such as academic institutions, have been invited to provide input on migration policies, and have thus become part of the migration governance structure. Following feedback on the relatively limited role they played during the drafting of the 2016 National Migration Policy, CSOs were increasingly engaged in drafting the ensuing Diaspora Engagement Policy and the National Labour Migration Policy.

Migration policy formulation, implementation, and day-to day management of migration in Ghana is carried out through collaboration between national and international bodies. In terms of international stakeholders, traditional actors such as IOM, other UN agencies and ILO are included in both policy development and execution. In addition, two particularly active international actors on Ghana’s migration governance scene are the international organisation International Centre for Migration Policy and Development (ICMPD), and the German development agency ‘Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit’ (GIZ).

Migration policy in Ghana

Migration has gained a steady currency as a cross-cutting phenomenon that is central to development policy planning in Ghana. Spurred by international and national recommendations, the Mahama government (NDC) kicked of a process to develop an overarching policy framework to guide national migration governance. As a result, three main national migration policies have been drafted to provide a holistic and coherent governance of migration from, within, and into Ghana:

- The National Migration Policy

- The Diaspora Engagement Policy

- The Labour Migration Policy

While there have been institutional and policy developments in support of drafting and validating these, efforts remain to ensure implementation of the specific objectives the policies entail. Yet, as detailed below, the three policies make up the backdrop of Ghana’s current priorities and concerns related to migration. The process of creating these policies has been slow, and a long time has passed between initial inception and the official launch of the policies. The government faces challenges in terms of implementing the policies, and this may partly be related to the lack of targeted funding, as many stakeholders have ‘noted the need for renewed external funding’. (Mouthaan, 2019). Moreover, migration policy making in Ghana is politicised and has gained political traction since the mid-2000s, especially in certain areas and discourses (DGAP 2021; Adam et al., 2020). Although enabling broad political ownership, the change in government in 2017 (NPP) may thus have also affected the process of implementation.

Box 2: Goals within the National Migration Policy

- Ensuring effective coordination of existing migration-related policy and legislation

- Developing programmes, strategies and interventions that will enhance the potential of migration for socio-economic development

- Promoting and protecting the interests, rights, security and welfare of citizens and migrants within and outside Ghana

- Setting up the appropriate legislative and institutional frameworks for a comprehensive approach to migration management

- Facilitating the production and dissemination of accurate, relevant and timely data on migration within, into, and from Ghana

- Promoting a comprehensive and sustainable approach to migration management

- Providing an enabling platform for national, regional, and global migration dialogue

- Countering xenophobia, racism, discrimination, ethnocentrism, vulnerability, and gender inequality within and outside Ghana.

Table 1: Specific regulations used to govern migration-related issues in Ghana

|

Immigration |

Immigration Act of 2000 (Act 573); Citizenship Act 2000 (Act 591); Immigration Regulations of 2001 (LI 1691); Immigration (Amendment Act) 2012 (Act 848); Immigration Service Act, 2016 (Act 908) (repealing the Immigration Service Law, 1989 (PNDCL 226)). |

|

Immigration and Diaspora Relations |

Dual Citizenship (Amendment) Act 1996 (Act 527); Citizenship Regulations 2001 (L.I. 1690); Representation of People’s Amendment Act 2006 (Act 669) |

|

Human Trafficking |

Human Trafficking Act of 2005 (Act 694) and Human Trafficking (Amendment) Act 2009 (Act 784); The Human Trafficking Prohibition Regulations, 2015 (L.I. 2219) |

|

Asylum seekers and refugees |

Refugee Law of 1992 (PNDC Law 305D) |

|

Emigration and internal migration |

Constitution of Ghana of 1992 – guarantees the rights of Ghanaians to emigrate and the right of all persons to circulate freely within Ghana. |

|

Labour migration |

Labour Act of 2003 (Act 651); Labour Regulations of 2007 (LI 1833), Labour (‘Domestic Workers’) Regulations of 2020 (LI 2408). |

National Migration Policy

In April 2016, Ghana launched it’s ‘National Migration Policy’ with the aim to ‘promote the benefits and minimise the costs of migration towards the national development of Ghana.’ The policy addresses national concerns relating to migration, and it gives specific attention to certain cross-cutting themes and issues (Ministry of the Interior, 2016).

At the time of writing, the National Migration Policy, as a coherent body, has not been implemented, and there is no coordinating body in place to oversee the potential implementation. The Ghana National Commission on Migration (GNMC) was initially to be established to secure sound implementation, but in its absence pre-existing regulations and mechanisms are used to govern migration-related issues (see Table 1 for an overview of current legislation). Although not successful so far, efforts are being made to this end such as through the 2019 UN DESA funded inter-ministerial meeting to establish the GNMC (IOM, 2019a) and concerted efforts by GIZ and IOM to provide capacity building to key stakeholders in the migration governance space through the constitution of a Technical Working Group to explore a framework for the establishment of the GNMC). In its strategic plan for 2022-2025, IOM Ghana also mention the ambition to support the Government of Ghana in this regard. The process concerning the National Migration Policy was also affected by the political shift in Ghana, as the government coming to power in 2017 seem to have shelved many of the previous governments’ initiatives (Mouthaan, 2019). Despite constraints, some aspects of the National Migration Policy are being implemented with European sourced funding. Yet, these are primarily the projects related to migration management and border control that most closely align with European stakeholders’ interests, and not necessarily those of Ghana (Arhin-Sam et al., 2021).

Diaspora Engagement Policy

Alongside the National Migration Policy (NMP), Ghana is in the process of finalising a specific policy on diaspora relations (Diaspora Affairs, 2020). The Government of Ghana has made several efforts to engage with the Ghanaian Diaspora to harness their human and material resources towards the national development agenda. The Diaspora Engagement Policy (DEP) aims at promoting a constructive engagement between Ghana and its diaspora for the purpose of achieving sustainable development.

Box 3: The key strategic objectives of the Diaspora Engagement Policy

To promote capacity-building and enhancement of diaspora-homeland relationship for the mutual benefit of both parties

To provide legal instruments and programmes that extend some rights and privileges that Ghanaians in Ghana enjoy to their counterparts in the Diaspora

To strengthen systems for involving the Ghanaian Diaspora in mobilising resources for sustainable national development

To facilitate the production and dissemination of accurate and relevant data on the Ghanaian Diaspora in a timely manner to strengthen the homeland’s further sustainable engagement with the Diaspora

Source: Draft version of the Diaspora Engagement Policy

All the various types of migration from Ghana yield substantial flows of remittances to the country. In 2020, personal remittances received amounted to 4.3 billion USD, making up 6% of Ghana’s GDP (World Bank, 2020). Partly due to the importance of the remittance flows, the government has embarked upon deliberate and proactive policy initiatives as a means of engendering a sense of belonging with the broader Ghanaian diaspora, while enlisting the economic potentials associated with migration. Most recently, the organisation of the Ghana Diaspora Homecoming Summit in 2017, the Ghana Diaspora Celebration & Homecoming Summit, and the Year of Return in 2019 – major events aimed at recognising and celebrating the immense contributions to nation building by the Ghanaian Diaspora. A follow-up event to these is the 2020-2030 campaign, themed ‘Beyond the Return’. These types of engagement initiatives have fed into the content of the Diaspora Engagement Policy, and partly also the National Migration Policy and the National Labour Migration Policy.

The DEP was developed in the context of the rising stock of Ghanaian international migrants. The government saw a need for a national policy to constructively engage the Ghanaian diaspora to mobilise the diaspora, and to coordinate diaspora contributions to the national development agenda. The Dual Citizenship Regulation Act was launched in 2002, with the aim to enable willing emigrants to acquire Ghanaian citizenship and legal status to be involved in national affairs. Ghanaian foreign missions were also able to develop appropriate approaches to organise the Ghanaian diaspora and develop concrete measures to facilitate their return (Mouthaan, 2019; Quartey, 2009). Also, the “Right of Abode” law was passed in 2000 to allow all persons of African descent to be able to apply for and be granted the right to stay in Ghana indefinitely (Teye et al., 2017). Similar efforts include the creation of structures and institutions, such as the Migration Unit in the Ministry of the Interior, the Diaspora Affairs Unit in 2012, which was later upgraded to the Diaspora Affairs Bureau in 2014 in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration, and the Diaspora Affairs Office at the Office of the President. Although political representation of the diaspora is not legislated, the current government includes a number of former diaspora members holding positions in the cabinet and as ministerial directors (Mouthaan, 2019).

The core objective of the Diaspora Engagement Policy is consistent with current global patterns where many countries, especially sending countries in the Global South, actively create initiatives to connect with and benefit from their emigrants, no matter where they reside. Although the DEP has been finalised, at the time of writing, it is yet to receive cabinet approval. Despite the lack of implementation, several actors in Ghana remain engaged with the diaspora through numerous activities, though this is not yet guided by an overall, coherent strategy.

National Labour Migration Policy

In 2019, a draft of Ghana’s National Labour Migration Policy (NLMP) was validated. The National Labour Migration Policy seeks to improve structures concerning both immigrant and emigrant labour to draw the benefits of labour migration for a holistic development in Ghana.

The National Labour Migration Policy is yet to be launched, though there is an urgent need for labour agreements with the popular destination countries for Ghanaian migrants, especially in the Gulf Cooperation Council States. Ghana currently governs labour migration through the existing Labour Act of 2003 (Act 651) and the Labour Regulations of 2007 (LI 1833). Although the Multilateral Relations Bureau at MoFARI (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration) is expected to promote humane treatment of Ghanaian emigrants (Mouthaan, 2019), the clandestine nature of the recruitment process and the non-compliance of private recruitment agencies with labour policies and requirements still presents a challenge (Awumbila et al., 2017). The contravention in the application of the labour laws in recruiting workers to the Middle East is central to the abuses suffered since only the few licensed recruitment agencies comply with the labour standards (Awumbila et al., 2017; IOM, 2019b; Teye et al., 2019).

Box 4: Labour Migration Policy

The policy is guided by three main strategic objectives:

- To promote good governance of labour migration

- To strengthen systems for the protection and empowerment of migrant workers and their families

- To strengthen mechanisms to maximise the developmental impacts of labour migration

The policy is divided into four key implementation areas:

- Creating a responsive governance system for labour migration

- Protecting and empowering labour migrants and their families

- Harnessing the potentials of labour migration for national development

- Strengthening labour market and migration information systems for evidence-based policy making in Ghana

Part II: International migration policy relations

This part of the EFFEXT background paper focuses on Ghana’s relationship with, and role vis-à-vis, international migration policy processes. More specifically, it aims to shed light on how Ghana’s collaboration with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union (AU), and European actors, including EU and individual European states, have influenced the development and implementation of national migration policies.

Ghana’s collaboration with states and state unions is closely related to Ghana’s collaboration with international organisations and relations to international legal frameworks for migration. In terms of organisations, Ghana has longstanding ties with the UNHCR, the IOM and the ILO, and in terms of international processes, Ghana has become more prominent in recent years. It actively participated in the development of the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), and is a key participant of the Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD).

In addition to its collaboration with European and African states, which is detailed below, Ghana has established bilateral agreements with other specific countries concerning cooperation on labour and/or migration. These include the labour export agreement with Qatar; the US-Ghana Trade and Investment Framework Agreement; and agreements with Turkey (and Kenya) centred on the development of partnerships in Air Services and Trade (IOM, 2018). There are on-going discussions with other Gulf States such as Saudi Arabia to sign bilateral labour agreements with Ghana.

Regional policy context

Contextualising Ghana’s migration governance, the two key regional stakeholders are the AU and ECOWAS. In addition, Ghana is involved in the promotion of dialogue and cooperation on international migration at the regional level through other platforms, with the key examples of the Migration Dialogue in West Africa (MIDWA) and the Mediterranean Transit Migration Dialogue (MTM). MIDWA was established in 2001 as a platform to encourage ECOWAS member states to discuss and collaborate on shared regional migration issues. MTM was established in 2003 to facilitate informal and consultative communication between migration officials in origin, transit, and destination countries in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. Although primarily aimed at enabling inter-continental dialogue, the Rabat process (established in 2006) has also been relevant in the regional context as it enables participating states to engage in dialogue on migration-related policy processes.

AU: Migration governance frameworks and the ‘Free Movement Protocol’

The African Union has designed policy frameworks and programmes to guide migration management across the continent, and some of these were used to provide the guiding principles for the development of the Ghanaian migration policies. One such example is the AU Migration Policy Framework (established in 2006 and recently updated) which provides guidelines for promoting free movement in Africa and assists African Governments with the development of national migration policies. The AU Joint Labour Migration Programme also seeks to support effective implementation of intra-regional migration policies on the African continent. A recent AU Free Movement Protocol is relevant as it guides Ghana’s work to cooperate with other African countries on migration management. The first 10-year implementation plan (2014–2023) of Agenda 2063 of the African Union Free Movement (African Union Commission, 2015) protocol outlined, among other criteria, the following:

- the need to domesticate all free movement of person protocols;

- that visa requirements for intra-African travel should be waived by 2018;

- that opportunities offered to regional economic community citizens should be extended to non-community citizens;

- that legal frameworks for the issuance of an African common passport should be adopted by 2023.

The implementation of the AU free movement protocol follows the same phases of implementation as the ECOWAS protocol, which is detailed below. Phase 1 focuses on the implementation of the right of entry, phase 2 on the implementation of the right of residence, and phase 3 on the implementation of right of establishment. Yet, the implementation of this framework has been quite slow and many countries are reluctant to freely open their borders due to fears that immigrants will compete with nationals for jobs. However, there has been modest progress as some countries, including Ghana, have relaxed their visa restrictions for easy entry of African travellers.

In 2018, as part of the broader efforts to facilitate movements of good and services, the AU established the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and trade commenced on 1 January 2021. Ghana played a pivotal role in the establishment of AfCFTA, and its secretariat is based in Accra. The AfCFTA, potentially the largest free trade area in the world, also seeks to facilitate the movement of labour within its member states. As with the free movement protocol, broader regional integration efforts provide opportunities for Ghanaian regional collaboration on migration within the AU.

ECOWAS: The ‘Free Movement Protocol’ and the ‘Common Approach to Migration’

Ghana is a founding member of ECOWAS, and has played a major role in the promotion of cooperation and integration of the ECOWAS countries since the treaty was signed in 1975. The ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol was adopted in 1979 and aims to encourage intra-regional mobility by removing barriers to free movement and ensuring citizens of ECOWAS member states enjoy the same rights as nationals in the country of residence. This is highlighted in the revised ECOWAS Treaty of 1993 Article 3 (1): “the removal, between Member States, of obstacles to the free movement of persons, goods, services and capital, and to the right of residence and establishment”. Based on this protocol, citizens of ECOWAS member states are not required to apply for a visa before entering another ECOWAS country for stays of up to 90 days, though any extension to this should to be approved by the relevant authorities (Awumbila et al., 2014; 2018).

As the AU, the ECOWAS face challenges when it comes to implementing its Free Movement Protocol, and originally this would be done through the same three phases as adopted by the AU. To enable its operation, the potential implementation is supported by a number of supplementary protocols, including:

- 1985 Supplementary Protocol A/SP.1/7/85: This Supplementary Protocol requires that ECOWAS Member States provide valid travel documents to their nationals and provides guidelines for protecting irregular immigrants and citizens who are to be expelled from host countries.

- 1986 Supplementary Protocol A/SP.1/7/86: This Supplementary Protocol proposes that Member States should grant all ECOWAS citizens the right of residence for the purpose of seeking and carrying out income earning employment. The citizens of Member States are expected to enjoy the same rights as nationals.

- 1990 Supplementary Protocol A/SP.2/5/90: This Protocol marks the Third Phase of the Implementation of the Free Movement Protocol and Directs ECOWAS member states to grant community citizens the right to settle and establish in other Member States.

In recent years, other ECOWAS policies and programmes aimed at facilitating migration for work have been adopted, including the ECOWAS General Convention on Social Security; ECOWAS Employment Policy; and ECOWAS Convention on the Recognition and Equivalence of Degrees, Diplomas, Certificates in Member States.

Box 5: ECOWAS' six principles for effective migration management (2018)

To address the challenges in implementing the ECOWAS protocol, the ECOWAS Heads of State and Government adopted the non-binding ECOWAS common approach to migration in 2018. The approach provides guidelines for ensuring effective migration management based on the following six principles:

- Free movement of persons within the ECOWAS region;

- Promoting regular migration as an integral part of the development process;

- Combating human trafficking;

- Harmonising migration-related policies;

- Protecting the rights of migrants and forcibly displaced persons;

- Recognition of the gender dimension of migration.

Implementation of the ECOWAS Free movement Protocol in Ghana

The Government of Ghana has made efforts to incorporate the provisions of the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol, especially those relating to the Right of Entry, migration governance and policy development into their own policy making (Teye et al. 2019). Indeed, the provisions of the ECOWAS free movement protocols have contributed to the discussions on border management in Ghana. The protocol provides guiding principles for the development of the NMP and the NLMP in Ghana, both of which recognise the need to facilitate free movement. Following the protocols, visa and entry requirement for stays of up to 90 days have been abolished for citizens from Western African countries. Ghana has also adopted the harmonised “Immigration and Emigration Form of ECOWAS Member States,” to simplify cross-border formalities in the sub-region, and since May 2000 it has been using the ECOWAS common passport. Yet, while some countries in the ECOWAS region have been allowing travellers to use identity cards as travel documents, Ghanaian immigration officials at the borders do not accept such cards, creating challenges at the border (Awumbila et al., 2018). Additionally, ECOWAS citizens may appear at the borders without valid travel documents. Harassment from border officials demanding unofficial payments is another challenge facing travellers, including ECOWAS citizens (Teye et al. 2019).

Ghana generally allows ECOWAS citizens to work in the country, though it primarily has focused on efforts to enable skilled labour migration. In the financial sector in Ghana, for instance, several businesses are owned and managed by ECOWAS citizens and a number of Nigerian financial institutions have been able to establish branches in Ghana as a result. In order to facilitate skills transfers in the sub-region, Ghana is participating in the Intra-African Talent Mobility Programme, which aims to create ‘Schengen’ type mechanisms on skills mobility to promote economic integration and socio-economic development.

Despite its efforts, not all ECOWAS provisions on the right of residence and right of establishment, have been effectively implemented. For instance, work permits are only issued to migrant workers, including ECOWAS citizens, when there is ‘proof that the skills possessed by the migrant do not exist locally’ (Teye et al., 2019). Additionally, migrants from all countries, including those from the ECOWAS region, are only legally able to work in the public sector under special, individual arrangements (Teye et al., 2015). Ghana’s Investment Act of 2013 also restricts migrants from engaging in ‘low capital economic activities’ (such as petty trading, driving taxis, hairdressing and so forth) and also from investing in business, below a high capital requirement threshold (Teye et al., 2019). The contradictions in policy have led to clashes between Nigerian and Ghanaian petty traders, and the governments of the two countries.

The NLMP identified these contradictions between the Ghana Investment Act and the ECOWAS free movement protocol as one of the key issues to be resolved, stating:

There are inconsistencies between Ghana’s guidelines for issuing work permits and the right of establishment of the Free Movement Protocol. While the protocol grants all ECOWAS citizens’ rights of establishment, all non-nationals in Ghana are required to obtain work permits. In addition, Ghana’s Investment Act, 2013 (Act 865) prohibits all migrants, including ECOWAS citizens, from engaging in certain economic activities (GoG, 2020, pp 51).

To address these challenges, the NLMP proposes to ‘(r)eview national legislative instruments to resolve contradictions between them and ratified international conventions and regional protocols on mobility, migration and citizenship,’ and ‘(e)nsure that procedures for issuing work permits are in line with ECOWAS free Movement Protocols’ (GoG, 2020, pp 52).

While ECOWAS officials agree that Ghana should take steps to urgently address the contradictions between national policies and ECOWAS free movement protocols, Ghanaian traders’ associations have been putting pressure on the government to fully implement the provisions of the Ghana Investment Act (Act 865) which will prevent ECOWAS citizens from operating small-scale businesses reserved for Ghanaians.

Europe-Ghana relations on migration

In view of Ghana’s position as one of the relatively economically promising and politically stable countries in West Africa, the EU has collaborated with Ghana in managing both labour and forced migration within and from the ECOWAS region for many years. However, Ghana’s relationship with the EU, as well as with individual European countries has gone through several twists and turns in line with changing migration landscapes, and the corresponding interests of Ghana and its European counterparts. Yet, since the early 2000s, cooperation between the EU and Ghana has in general been geared towards four broad areas, namely: the facilitation of free movement in the region, the development of national migration policies, the control and reduction of irregular migration, and the promotion of return and reintegration (see Table 2 for an overview of focus areas, underlying motivations and examples of key projects). In addition, recent efforts have been targeted towards training and capacity building across policy areas, with the aim of strengthening Ghanaian stakeholders’ migration governance capacity. European states and the EU have also funded agricultural and development programmes, for example, vocational training, partly aimed at reducing irregular migration (Kandilige et al., 2022). This section describes specific agreements and mechanisms under each of the four key areas of cooperation and provides some preliminary reflections on the role European stakeholders have played in these policy fields in Ghana.

Table 2: Key areas of collaboration in EU-GHANA migration policy relations

|

Period |

Focus area |

Underlying motivating factors |

Key projects with implications for Ghana |

|

2000–2018 |

Facilitation of free movement in West Africa |

|

|

|

2012–2019 |

Development of national migration policies |

|

|

|

2015–Present |

Limitation of irregular migration |

|

|

|

2015–present |

Return migration and reintegration |

|

|

Source: Authors’ own compilation

Collaboration on free regional movement

In the early 2000s, European collaboration agreements and mechanisms focused heavily on the facilitation of free movement in West African countries, including Ghana. This aligned with the EU’s desire to facilitate intra-regional migration for development in West Africa as an alternative to migration to Europe. Ghana and the EU’s interest in protecting migrants’ rights in West African countries of destination also shaped these agreements. Ghana collaborated with the EU and EU countries to implement programmes that sought to facilitate free movement. This section includes many of the initiatives, financed and supported by European stakeholders, that have sought to enhance and facilitate intra-regional migration in ECOWAS over the last two decades.

First, an early initiative was the ECOWAS/SPAIN Fund on Migration and Development (2007-2011). This project was funded by the Spanish government and aimed to support ECOWAS to develop and implement the ECOWAS Common Approach on Migration. Ghana benefited in the form of financial and technical support for the development of migration management programmes. The project also offered technical training on the ECOWAS protocol for officials of ministries, agencies, and the media. Swiftly following was the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP)-EU project that sought to facilitate mobility in the ECOWAS region (2012-2014). The project provided the Centre for Migration Studies (CMS) in Ghana with EU funding to work with country level researchers to conduct studies on barriers to free movement in all 15 ECOWAS countries. The findings of the country studies were used to develop recommendations for facilitating free movement in Ghana and other ECOWAS countries.

From 2013-2018 Ghana received EU and ECOWAS funded support to the Free Movement of Persons and Migration in West Africa (FMMM) project. With a budget of over 26 million Euros, the FMMM project provided technical and financial support for the implementation of the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol and the ECOWAS Common Approach on Migration. Migration data management, border management, labour migration and counter-trafficking were the key areas covered. Specifically, Ghana obtained funding to organise training for public officials and media personnel on implementation of the protocol. Part of the funding also supported the drafting of the Labour migration policy in Ghana, under the auspices of IOM and the Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations.

With the CMS as a key partner, Ghana was involved in the Migration and Development (MADE) West Africa project (2017-2020), funded by the EU as part of the Rabat Process. The MADE project sought to facilitate free movement and to protect the rights of migrants in the ECOWAS region. Under this project, the CMS conducted a study on free movement and migrants’ rights in Ghana and Sierra Leone. The study revealed that free movement is affected by several factors, including border harassment, lack of travel documents, low level of knowledge on the protocols, porous nature of the borders, and resource constraints. Based on the findings, and funded by EU seed money, the Media Network on Migration (MENOM) Foundation and CMS implemented a series of activities, including training programs for various migration governance stakeholders. Multistakeholder workshops were also organised to develop road maps for enhancing free movement, reduce harassment at the border and improve the protection of migrant rights.

Through different means, European-Ghanaian collaboration has influenced the implementation of the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol in Ghana. Ghana’s participation in the MADE and the MMM projects have contributed to increased awareness of the Protocol and furthered efforts to reduce both harassment at Ghana’s borders and other barriers to free movement. The EU’s long history of implementing regional integration and free movement has provided learning experiences on how to manage the challenges of free movement for Ghana, and other ECOWAS countries. One example of this is the EU-funded 2015 conference on AU Free Movement Protocol held in Rwanda. The EU participated in the conference and shared ideas on how to proceed to enhance free movement. However, we also see that the priority areas of Ghana may have shifted in response to EU funding and funding opportunities and Ghanaian, and other actors in West Africa, have defined new priority areas which are not primarily focused on ensuring the implementation of the protocol (Adam et al., 2020).

Moreover, the EU’s recent bilateral cooperation with countries such as Niger, Mali, Libya to counter irregular migration of ECOWAS citizens across the Sahara Desert and towards Europe has been seen by some as violating migrants’ rights and/or delaying the effective implementation of the Free Movement Protocol (see Castillejo, 2019; Zanker et al., 2020; Arhin-Sam et al., 2021). According to Zanker et al. (2020), although the EU is not opposed to free movement within Africa, it has, since 2015 focused more on preventing irregular migration to Europe through strict border control, combating human trafficking, and enforcing returns of undocumented migrants.

Collaboration on the development of national policies

From 2012 to 2019, the EU increased its technical and financial support to Ghana to facilitate the development of the National Migration policy, the National Labour Migration Policy and the Diaspora Engagement Policy (see Table 3 for an overview of funders contributing to the policy development processes). Ghana’s main interest with developing national policies was to harness the benefits of migration through, for example, increased labour migration and regional free movement within ECOWAS. This aim was partly shaped by the recommendation in the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda I (GSGDA 2010-2013) that Ghana needed a comprehensive policy that could be used to manage all aspects of migration. The aim was also in line with the earlier calls from the AU and ECOWAS that member states should develop national migration policies (in the 2006 AU Migration Policy Framework for Africa and the 2008 ECOWAS Common Approach on Migration). Finally, it was also in line with the general trend in the international community, and EU – through the IOM – was interested in boosting the national policy frameworks on migration in Ghana. As the Ghanaian government lacked the funds to develop these migration related policies, the EU’s willingness to support the development of migration policies was very attractive. Part of the funds were used to hire consultants from the CMS and to organise policy-development workshops (Arhin-Sam, 2021).

The motivations for cooperation on the development of the DEP and the NLMP were similar. Both the government of Ghana and the European Union were keen to develop these policies, for example, to maximise the developmental benefits of migration. To this end, DEP would help Ghana leverage remittances for socio-economic development (Teye et al., 2017). Another underlying motive for the NLMP was to provide a legislative and regulatory framework for protecting migrants and their families in countries of destination, especially in the Middle East, as increased public attention had been given to the serious violations of migrants’ rights. The 2030 Global Development Agenda, which called on governments to mainstream migration into development planning, also influenced both the government of Ghana and the EU as they worked together to develop these migration-related policies. It is, therefore, no coincidence that all of Ghana’s three main migration policies have sections on migration and development where, for example, strategies have been stated for leveraging migrants’ remittances for development.

Table 3: National policy development and foreign funders

|

Policy |

Funders |

Timeline |

|

National Migration Policy |

EU |

Started 2012, launched 2016 |

|

Diaspora Engagement Policy |

EU, and EU member states such as Spain and Germany, through ECOWAS, GIZ, ICMPD and MIEUX initiative |

Started 2016, in the process of being finalized |

|

National Labour Migration Policy |

EU, IOM |

Started 2018, launched 2020 |

Turning to the question of whether European funders’ agendas influence the work on these migration policies in Ghana, it is important to underscore that the development of all three policies were, largely, funded by the EU. European stakeholders’ support also fed into the prioritisation in the policies. In recent work on Ghana and other ECOWAS countries’ domestic priorities on migration, Mouthaan (2019) and Bisong’s (2020) findings are consistent with previous research: they highlight that the EU does not adequately incorporate partner countries’ input, or if so, this is adjusted for during the process of implementation – which also seems to be the case in Ghana.

Some of the content of the Ghanaian policies is aligned with relevant documents from other EU agreements and meetings with the AU. This may be explained by the fact that both the EU and Ghana’s recent migration policy strategies are based on the 2030 Development Agenda. Yet, it merits attention that the process of policy drafting may have been influenced, for example, by Ghanaian stakeholders previous engagement with European stakeholders. Also, seeing that academics from CMS have been heavily involved as consultants in the drafting processes, it is reasonable to investigate critically how the consultants’ assessment may have been influenced by European funding arrangements. In practice, however, there are examples of agency on the part of Ghanaian consultants from the CMS, especially during the drafting of the National Migration Policy, who pushed back against European preference for a policy that is focused mainly on emigration of Ghanaians. This resulted in a policy document that covers emigration but also immigration, internal migration, the diaspora, and other cross-cutting issues such as migration and gender, migration and climate change, and statelessness among others.

Collaboration to limit irregular migration

The period from 2014/2015 onwards witnessed changes in the migration policy landscape in Europe. The spike in arrivals of refugees and irregular migrants, renewed EU’s efforts towards external migration control. The financial incentives provided by the EU to African countries seem to have increased Ghana’s interests for EU-Africa engagement in processes targeted to control irregular migration. International calls on the need to promote safe and orderly migration, which culminated in the development of the Global Compact for Migration, also influenced the EU’s and individual European states’ support to Ghana. Ghana has thus participated in several programmes, and received various financial incentives, meant to enable Ghanaian-European corporation on the control of irregular migration, both to the EU and within the West African region.

A relevant platform for EU-Ghana collaboration in this regard has been the Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development (i.e. the Rabat Process), which focuses on a range of migration issues, including the combat of irregular migration, migrant smuggling and human trafficking. It is also meant to enable legal channels of migration, though there have been few specific policy instruments introduced to this end. Regarding more specific incentives targeted to decrease irregular migration, Ghana has implemented EU funded programmes concerning border control and border management capacity building. In addition to improved physical and administrative control of Ghana’s territorial borders, initiatives are also aimed at information provision concerning the dangers of irregular migration and the opportunities of legal migration, and initiatives meant to increase local opportunities of employment, for example through vocational training and employment centres.

First, in terms of border control, an initial example was the Ghana Integrated Migration Management Approach (GIMMA) project, funded by the 10th European Development Fund. From 2014-2017, the programme sought to enhance the capability of stakeholders working on migration related issues, including border management capabilities. Two more recent border control initiatives are the EU funded ‘Strengthening Border Security in Ghana’ (SBS) project (2021 onwards) and the Danish funded ‘Strengthening Border and Migration Management in Ghana’ (SMMIG) project (2018 onwards). These are carried out by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), in collaboration with the Government of Ghana, and specifically the Ghana Immigration Service. These are targeted at combating irregular migration by improving Ghanaian border management, such as through enhanced equipment, vehicles, language skills and document fraud detection training of staff working on border posts.

Concerning the spread of information as a mean to limit irregular migration, it is relevant to mention the establishment of Migration Information Centres. Since 2015, centres have been established in popular migrant-source communities to sensitise the youth on the dangers of irregular migration (IOM, 2016 and 2018). These centres are receiving funding from various European stakeholders to improve their capacity, such as for instance through GIMMA and the 2022-2024 Spanish funded initiative ‘MigraSafe – Africa’. In addition to the centres, information or awareness raising campaigns are part of several European funded programmes. A relevant example is those that have been initiated under the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration, funded by the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Since the launch of this joint programme in 2017, the Government of Ghana, IOM, the EU Delegation to Ghana and other stakeholders have collaborated to organise more than 300 awareness raising sessions. In these campaigns, return migrants are often included to explain the dangers of migration to potential migrants. Other initiatives have, for example, included street art interventions in Accra and Takoradi, collaboration with Ghanaian musicians, like Kofi Kinaata, and the ‘Playground’-, the ‘No Place Like Home’-, and the multimedia ‘Let’s Talk Migration’ campaigns (IOM, 2021a).

In terms of collaboration to limit irregular migration, it is evident that the EU and Ghana have both common and different interests. The dangers of irregular migration are of political relevance in both Europe and Ghana, though it is of greater relevance to European policymaking. In addition, with particular reference to the increased level of conflict in the Sahel, both Ghanaian and European stakeholders highlight the need for improved security measures in Ghana, including the need for strengthened border control. Many of the programmes implemented by GIS are linked to the control of irregular migration by using EU funding, even though preventing irregular migration to Europe has not been a key issue in Ghana. As noted by Mouthaan (2022), the increased focus on security measures in Ghana may be at the expense of free mobility in ECOWAS.

Collaboration on return and reintegration

Though not a new endeavour, Ghana and the EU have increasingly sought to collaborate on return migration and reintegration – particularly after the 2015 spike in flows to Europe. To this end, several European funded initiatives related to return and reintegration have been established in Ghana, also in collaboration with the IOM and the GIZ.

Many of the migrants who have returned to Ghana over the last decade have been supported by the EU and the IOM Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) programme (Serra and Rudolf, 2020), which is devised primarily by the European Return and Reintegration Network (ERRIN). The network was established in 2018, by 15 European partner countries seeking to ensure that migrants return to their home countries in a dignified and humane manner. Another ERRIN initiative, the German funded Gov2Gov programme on return and readmission management, has for example focused on capacity building in the Ghanaian national administration, and organises training sessions to promote voluntary return (ERRIN, 2021). Since 2017, the EU has also supported return and reintegration in Ghana through the ‘IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration’, and through the EUTFA project ‘Strengthening the management and governance of migration and the sustainable reintegration of returning migrants in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Guinea, Guinea Bissau and Chad’. As part of the latter framework, IOM Ghana was supported with 3 000 000 EUR to, amongst other initiatives, promote return and reintegration, and increase awareness on irregular migration in local communities (EC, 2021).

Several initiatives have also been focusing on the reintegration of Ghanaian returnees. An effort to guide reintegration processes in Ghana came with the introduction of “Standard Operating Procedures for Reintegration of Returnees in Ghana” which were produced through the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration in 2020. These procedures were developed to “provide a common understanding and ensure a consistent approach in the context of all returns to Ghana and the returnees’ subsequent reintegration back into their communities of return” (IOM, 2020b). Among the many stakeholders involved in reintegration, GIZ stands out as a key actor, working with several partner organisations to enhance the skills and opportunities of returnees. Unlike most European funded return migration programmes, which mainly support the return of vulnerable migrants, the German government, through GIZ, also implements a ‘Migration for Development’ project which also seeks to facilitate the return of highly skilled migrants (GIZ, 2022).

Not limited to returnees, but also with the aim of improving reintegration processes, a key German contribution has been the establishment of the information hub ‘the Ghana-German Centre for Jobs, Migration and Reintegration’ (GGC). The centre has two main programmes, the Programme Migration and Diaspora (PMD) and the Programme Migration and Employment (PME), while also carrying out a range of activities, such as the 2021-launched ‘Migration and Employment podcast’, which also sought to educate young potential migrants on the dangers of irregular migration, and several job fairs both in Accra and elsewhere (GIZ, 2021).

Despite the various, and the increase in, EU-funded initiatives on return and reintegration, Ghana has not shown significant interest in cooperating with the EU on implementing forced returns from Europe. For instance, while the 2016 Joint Declaration mentioned a mutual interest in cooperation between Ghana and the EU to facilitate forced return of undocumented migrants to Ghana, the government has not given massive support in the provision of necessary documents to allow the deportation of undocumented migrants to Ghana (Arhin-Sam et al., 2021). The lack of commitment from the Ghanaian government on forced returns could be because the notion of forced returns is in direct contrast with its policies on diaspora engagement and encouraging diaspora to send remittances to Ghana (Arhin-Sam et al., 2021). Additionally, reintegration of those ‘returned’ can cause an upheaval: according to Ghanaian officials the “abrupt return” of Ghanaians posed “significant challenges” from 2011 to 2012 (Ghanaian NMP: Ministry of Interior Ghana, 2016; Mouthaan, 2019).

In general, most of the Ghanaians that have been assisted to return in recent years have been persons ‘trapped’ in other African countries, primarily Libya, followed by Niger and Algeria. According to IOM (2021b), over 1800 individuals have been supported to return through ‘Voluntary Humanitarian Return Assistance’ from elsewhere in Africa since 2017. The returnees from Libya and other North African countries were largely those attempting to clandestinely enter Europe, and many of the returnees from Niger were trying to enter Europe through the Sahara. Returns also take place from the Gulf countries, but these are generally not assisted by international organisations or European donors.

The Ghanaian government has been particularly evasive when it comes to returns of migrants from Europe. Arhin-Sam et al. (2021) argue that Ghana’s lack of interest in forced returns from EU countries can be explained by the fact that promoting forced returns can potentially harm Ghana’s diaspora engagement programmes, reduce remittance flows, and potentially cause unemployment at home. There are also fears that political opposition parties can use return cooperation with European partners to gain political support and thereby threaten the power of the ruling party (Arhin-Sam et al., 2021: 4).

Concluding remarks

This Background Paper has provided a brief review of migration policy and governance in Ghana, including an overview of Ghanaian migration dynamics, the migration governance structure, the legislative framework, and migration policies in Ghana. It has reviewed the primary areas where Ghana is engaged in international collaboration, within the West African region and beyond. Aligned with the aim of the Background Paper, to guide the fieldwork and case selection in the EFFEXT project, this section offers some reflections on the trends in the relationship between the European externalisation agenda and Ghana’s migration governance and policy. It presents some key questions that remit further exploration when studying the effects of European migration management in Ghana.

Since the turn of the millennium, the EU and individual European states have increasingly collaborated with the Ghanaian government on migration-related issues. Yet, over the last ten years and particularly since the 2014/2015 Mediterranean migration crisis, Europe has become more deeply involved in shaping the development of Ghana’s migration policies and governance structures. This has happened through various platforms and instruments under the umbrella of externalisation policy. The European states’ primary function as donors is evident through the large-scale financial assets that have been provided to strengthen ongoing work in Ghana, such as through the financial support towards the national migration policy making processes (the NMP, the NLMP, and the DEP), and to strengthen the capacity for sound migration management by supporting national institutions in their work on migration issues, such as work on strategy developments and capacity building among staff. In addition, European funding has been targeted towards more specific areas of migration governance, such as border management. Some of these were not previously key to the Ghanaian agenda on migration, such as migrant return and information provision. As exemplified through the various specific European-funded policy initiatives referred to in the previous parts of the paper, there has been a growing economic incentive for Ghanaian partners to work on policy areas that are in accordance with European migration-related ambitions, such as the ambitions to reduce irregular migration, particularly towards Europe, for example through increased border control measures targeted towards emigration, and local engagement with potential migrants. Yet, despite continued collaboration and an increase in policy on paper, many of the main initiatives’ implementation processes have been slow, and in some instances, come to a halt, such as with the efforts to strengthen return mechanisms from Europe and the finalisation of the work on the national policies on migration, labour migration and diaspora engagement. This has also been highlighted in previous research, and has been explained partly by contrasting national, West African regional, and European political agendas, unstable governance and management structures, and national and local political dynamics (see for example, Adam et al., 2020; Arhin-Sam et al., 2021; Bisong, 2020; Castillejo, 2019; Mouthaan, 2019; Zanker et al., 2020). On the other hand, numerous initiatives have been carried out in accordance with donors’ plans, such as programmes on information provision, e.g. executed by the IOM, and initiatives focused on capacity building or border management, e.g. executed by the ICMPD.

A potential overall trend in terms of the development of the European migration-related involvement in Ghana, is that the focus on control and limitation of migration has increased since the 2015 incidents in the Mediterranean. While the early 2000s saw more initiatives and support in line with the aims of free mobility within the ECOWAS, this has been less visible on European donors’ agendas in the past years. Moreover, following the slow implementation of some European funded migration control measures in Ghana, increased funding has been steered towards capacity building and training. This may signal a Ghanaian ambiguity towards migration governance: international migration within and beyond the region is - for many - part of life, and increased control, return and border securitisation is thereby not a winning political card.

Thus, while Ghanaian ministerial interest in collaboration with European partners has been apparent for decades, and the interest in developing migration governance structures has grown, the dynamics in terms of the strengths of the collaboration across different policy areas, is partly shaped by Ghanaian internal politics and agendas. Yet, for European stakeholders and donors, it is key to have strong and stable institutional partners to collaborate with to secure sound implementation, and this may have contributed to the donors’ push for focusing on capacity building – which has happened across many of the fields of collaboration. This change in donors’ focus and Ghanaian interests, not only include specific mechanisms in migration policy areas, but capacity building and training of stakeholders, is likely also driven by broader international processes, such as the 2018 Global Compact for Migration that spearheaded the process of making ‘capacity building’ an intrinsic part of international collaboration on migration.

Based on the tendencies of migration policy making, collaboration and implementation in Ghana, as outlined in the above and in previous research, there are several questions that merit further investigation. This includes a deeper dive into the content, practices, and outcomes of capacity-building processes – across various areas. Moreover, as most existing research focuses on policy agendas and making at the national level, including studies of various stakeholders’ role in these processes, an important next stage is to study more specific donor-funded projects on migration. This would include local level stakeholders’ involvement in implementation processes, and migrants, potential migrants, and others’ experiences of the implemented policies. Future research avenues are also to be found in relation to the four specific areas of collaboration as outlined in the above. Though these must be seen in relation to cross-cutting issues concerning Ghanaian migration governance, some specific questions remain unanswered:

First, in relation to the collaboration on free regional movement:

- While there seem to have been a shift in European donors’ migration-related focus in Ghana over the last twenty years, with reference to the factor that fewer externally funded projects concern free mobility in ECOWAS, how does this relate to the development of national priorities? Has there been a corresponding shift in the migration agenda among Ghanaian stakeholders?

- As increasing funds are spent on migration management in the form of border control and securitisation, how does this influence the prospects for free regional movement?

Second, in terms of the development and implementation of national policies:

- While the development of the Ghanaian national migration-related policies has been largely funded and also supported by European donors, in what ways and with which effects are European actors and policies shaping current processes of implementation? This question pertains to both the NMP, the NLMP and the to-be-launched DEP.

- With reference to the longstanding relations on migration governance with European and other international partners, how has this influenced normative understandings of migration and migration policy at the governmental level and among local implementing partners in Ghana?

Third, concerning the field of irregular migration:

- As there has been increased focus on border management as a mechanism to control irregular migration (primarily directed towards Europe), how has this influenced local mobility patterns and experiences of border crossing?

- Several European funded projects have focused on information provision and sensitisation concerning the dangers of irregular migration, and previous research points to uncertainty regarding the effect on migration. Yet, in Ghana, does different information provision initiatives leave different marks? How do these initiatives affect local level stakeholders and populations, including non-migratory populations?

Fourth, in the areas of return and reintegration:

- Ghana does not collaborate on large-scale return from any European country, yet several individuals return through organised programmes (voluntary and forced). To this end, European funded services are set up to provide returnees with information, but limited knowledge is available regarding the practical implications of this. Therefore: How are these services used? Who are the beneficiaries? And, how do they impact migrants’ experiences of return?

- Different return and reintegration arrangements are in place to support returnees. Some of them are funded by European actors and targeted at specific groups of returnees. How do the reintegration services differ, how are the experiences, and how are the local conceptions of these services?

References

Abdulai, A., & Rieder, P. (1999). Internal migration and agricultural development in Ghana. Scandinavian Journal of Development Alternatives and Area Studies, 18(1), 61-74.

Abdul-Korah, G. B. (2011). ‘Now If You Have Only Sons You Are Dead’: Migration, Gender, and Family Economy in Twentieth Century North-Western Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46(4), 390-403.

Ackah, C. and Medvedev, D., (2010). Internal migration in Ghana: Determinants and welfare impacts. Background paper prepared for 2010 World Bank report. Available from http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-5273

Adepoju, A. (2003). Continuity and changing configurations of migration to and from the Republic of South Africa. International Migration, 41(1), 3-28.

Agblorti, S. K. (2011). Refugee integration in Ghana: The host community’s perspective. UNHCR, Policy Development and Evaluation Service.

Agyei, J., & Clottey, E. (2007). Operationalizing ECOWAS protocol on free movement of people among the member states: Issues of convergence, divergence and prospects for sub-regional integration. International Migration Institute, University of Oxford. http://www.imi.ox.ac.uk/publications/operationalizing-ecowas-protocol.

Amoako, C. and E.F. Boamah 2015 The three-dimensional causes of flooding in Accra, Ghana. International journal of ran Sustainable development, 1:109129.

Anarfi, J. K. (1982). International Labour Migration in West Africa: A Case Study of the Ghanaian Migrants in Lagos, Nigeria. Accra: Regional Institute for Population Studies; Legon: University of Ghana.

Anarfi, J. K., K. Awusabo-Asare, et al. (2000). ‘Push and Pull Factors of International Migration. Country report: Ghana. Eurostat Working Papers 2000/E (10).

Anarfi, J., Kwankye, S., Ababio, O. M., & Tiemoko, R. (2003). Migration from and to Ghana: A background paper. University of Sussex: DRC on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty.

Anarfi, J., P. Quartey & J. Agyei (2010) Key determinants of migration among health professional in Ghana. Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty Working Paper.

Arhin-Sam. K, Rietig, V and Fakhry, A (2021) Ghana as the EU’s Migration Partner: Actors, Interests, and Recommendations for European Policymakers. German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP)DG Report No 7. German Council on Foreign Relation.

Asante, F.A. and Amuakwa-Mensah, F., (2015). Climate change and variability in Ghana: Stocktaking. Climate, 3(1):78-99.

Asiedu, A. B. (2010). Some perspectives on the migration of skilled professionals from Ghana. African Studies Review, 53(1), 61-78.

Awumbila, M., Benneh, Y., Teye, J. K., & Atiim, G. (2014). Across artificial borders: An assessment of labour migration in the ECOWAS region. Brussels: ACP Observatory on Migration.

Awumbila, M., & Teye, J. K. (2014). Diaspora and migration policy and institutional frameworks Ghana country report.

Awumbila, M., Deshingkar, P., Kandilige, L., Teye, J. K., & Setrana, M. (2017). Brokerage in migrant domestic work in Ghana: complex social relations and mixed outcomes.

Awumbila, M., Manuh, T., Quartey, P., Tagoe, C., & Bosiakoh, T. (2008). Migration country paper: Ghana. Retrieved from https://www.imi-n.org/files/completed-projects/ghana-country-paper.pdf

Awumbila, M., Teye, J. K., Litchfield, J., Boakye-Yiadom, L., Deshingkar, P., & Quartey, P. (2015). Are migrant households better off than non-migrant households. Evidence from Ghana. Migrating out of Poverty Working Paper, 28.

Awumbila, M., Teye, J., Kandilige, L., Nikoi, E., & Deshingkar, P. (2019). Connection men, pushers and migrant trajectories: examining the dynamics of the migration industry in Ghana and along routes into Europe and the Gulf States.

Beals, R. E. and. Menezes, R., E. (1970). ‘Migrant Labour and Agricultural Output in Ghana’.

Bisong A. (2020). ‘The impact of EU migration policies in Africa: Exploring the policy coherence of EU migration efforts’ Policy Brief. Caritas Europa and FES Brussels (October 2020).

Boahen, A. A. (1966). Topics in West African History. London: Longman.

Boahen, A. A. (1975). Ghana: Evolution and Change in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century. London: Longman.

Bruni, V., Koch, K., Siegel, M., & Strain, Z. (2017). Study on migration routes in West and Central Africa.

Castillejo, (2019) : The influence of EU migration policy on regional free movement in the IGAD and ECOWAS regions, Discussion Paper, No. 11/2019, ISBN 978-3-96021-101-3, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp11.2019

Diaspora Affairs, 2020, https://diasporaaffairs.gov.gh/tag/diaspora-engagement-policy/

ECOWAS (1999) ECOWAS Treaty (www.ecowas.int)

Essuman-Johnson, A. (2003). Ghana’s policy towards refugees since independence. Ghana. Social Science Journal (New Series), Vol. 2, No. 1, p. 136-161.

UNHCR (2017) End of year Report. Available at https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/pdfsummaries/GR2017-Ghana-eng.pdf, accessed 10.03.2023

Ghana Refugee Board (2022) Our Refugee. Available at https://www.grb.gov.gh/, accessed 24.05.2022

Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (2017). Doing business in Ghana. Accra: GIPC

Ghana Statistical Service (2013) 2010 Population & housing census: National analytical report. Ghana Statistics Service.

GIS (2019) Ghana Immigration Service Annual Report 2018. Accra.

GIZ (2021) Ghana. Available at: https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/324.html, accessed 10.03.2023

GIZ (2022) Making a successful fresh start possible in countries of origin. Available at https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/62318.html, accessed 10.03.2023

GoG (2020) National Labour Migration Policy 2020-2024. Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations. Available at https://cms.ug.edu.gh/sites/cms.ug.edu.gh/files/National%20Labour%20Migration%20Policy%20.pdd, accessed 10.03.2023

IOM (2016) Ghana integrated migration management approach,” January 2016: https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/docs/ghana/GIMMA-Information-Sheet-January-2016.pdf, accessed 02.05.2021

IOM (2018) Migration Governance Snapshot: the Republic of Ghana, IOM UN Migration, https://www.migrationdataportal.org/overviews/mgi/ghana#6, accessed 22.10.2021

IOM (2019a) IOM supports the Government of Ghana in the establishment of the IOM Regional Office for West and Central Africa. Available at https://rodakar.iom.int/news/iom-supports-government-ghana-establishment-ghana-national-migration-commission, accessed 03.10.2023

IOM (2019b). Ghanaian Domestic Workers in The Middle East. Summary Report, September. Available at https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/docs/ghana//iom_ghana_domestic_workers_report_summary-finr.pdf, accessed 10.03.2023

IOM (2020a) Migration in Ghana: A country profile. Geneva: IOM.

IOM (2020b) Reintegration of returnees in Ghana. Available at https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/country/docs/ghana/sops_for_reintegration_of_returnees_in_ghana_sept_2020.pdf, accessed 03.10.2023

IOM (2021a) Stories of Return and Reintegration. Available at 2021%20EUTF%20Success%20stories%20-%20comp.pdf (iom.int), accessed 10.03.2023

IOM (2021b) EU-IOM Joint Initiative Migration Protection and Reintegration in Ghana. Available at https://rodakar.iom.int/news/eu-iom-joint-initiative-migrant-protection-and-reintegration-ghana-%E2%80%93-4-years, accessed 03.10.2023

ICMPD (2018) Strengthening Border and Migration Management in Ghana (SMMIG). Available at https://www.icmpd.org/our-work/capacity-building/regions/africa/strengthening-border-and-migration-management-in-ghana-smmig, accessed 01.05.2021

Johnson, K. T. D.-G. (1974) Population Growth and Rural Urban Migration with Special Reference to Ghana. International Labour Review 109: 471-85.

Jonah, F. E., Mensah, E. A., Edziyie, R. E., Agbo, N. W., & Adjei-Boateng, D. (2016). Coastal erosion in Ghana: causes, policies, and management. Coastal Management, 44(2), 116-130.

Kandilige, L., Teye, J., Setrana, M., and Badasu, D. M. (2022). ‘They’d beat us with whatever is available to them’: exploitation and abuse of Ghanaian domestic workers in the Middle East. International Migration. DOI: 10.1111/imig.13096

Kandilige, L., Teye, J. K., M, Setrana, & Badasu, D. (2019) Ghanaian domestic workers in the Middle East. (Summary Report, September, 2019), IOM, Ghana.

Kandilige, L. Teye, J.K., Vargas-Silva, C. & Godin, M. (2022) MIGNEX Background Paper, Migration-relevant policies in Ghana, Oslo: Peace Research Institute Oslo. Available at www.mignex.org/gha

Kufuor, K. O. (2013) When Two Leviathans Clash: Free Movement of Persons in ECOWAS and the Ghana Investment Act of 1994. African Journal of Legal Studies, 6(1), 1-16.