Engineering gender equality: The effects of aid to women's political representation

Liv Tønnessen

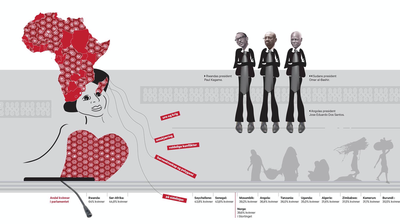

While the number of women holding parliamentary seats is slowly growing globally from 10% in 1995 to 17% in 2009, Africa is on the ‘fast track’ to women’s political representation.The number of female parliamentarians in African legislative assemblies has more than doubled since the Beijing Platform for Action from 1995 which called upon governments to “take positive action to build a critical mass of women leaders, executives and managers in strategic decision-making positions”. The critical mass was established at 30% seats for women in parliament.Currently Rwanda has the highest percentage of women in parliament in the world at 64 % outshining all of the Nordic countries.

The last decade, women’s political empowerment has been the biggest target area of Norwegian aid to women’s rights and gender equality with seven African countries on the top-10 list of gender marked Norwegian aid recipients, namely Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Sudan, Uganda, and Zambia. The theory of change underpinning this aid is that increasing the number of women (descriptive representation) in political decision-making processes is important for its own sake, but it is additionally regarded as a powerful tool to fight gendered laws, attitudes and injustices more generally. In short, it is expected to increase pro-women initiatives, acts and legislative outcomes (substantive representation) and to change patriarchal attitudes and make public perceptions more favourable towards women in politics (symbolic representation).

Recent studies of a related phenomenon, democracy assistance, have found that aid is clearly more effective in preventing backlash in newly democratized states, than fostering transitions from autocratic to democratic regimes. Based on this logic, the project explores whether gendered aid is most efficient in countries where there is a high degree of descriptive representation and a visible women’s movement to push and support female legislators to act in the interest of women. In these cases gender equality assistance might bring about processes that make descriptive representation effective in translating numbers into women’s substantive and symbolic representation. When, where and how is gendered aid most effective?

This project looks at the effects of aid on women's substantive (acting for women) and symbolic (role-modeling women) representation in Malawi, Sudan, Uganda and Zambia from 2007 until 2013. The starting point is 2007, when we saw a massive increase in Norwegian aid to women’s political empowerment in Africa. All the cases are main recipients of gendered Norwegian aid, but they clearly differ when it comes to both the visibility of women’s movements and descriptive representation. Whereas Uganda had a strong women’s movement and 31 % women in the national assembly in 2007, Malawi, Sudan and Zambia had weak women’s movements and low levels of descriptive representation. Yet, we know that since 2007 the cases represent uneven trajectories of developments in women’s descriptive, substantive and possibly also symbolic representation. How has gendered aid contributed in these processes? Besides building new empirical knowledge about the effects of aid to women’s political empowerment in previously understudied cases, the principle endeavor of this research is to generate new hypotheses about women’s substantive and symbolic representation, and in this way facilitate theory development and building a stronger base for informed policy.