Women in Local Government. A Potential Arena for Women’s Substantive Representation

How to cite this publication:

Asiyati Lorraine Chiweza (2016). Women in Local Government. A Potential Arena for Women’s Substantive Representation. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 13)

Local government is an important avenue for getting practical experience in participating in politics before moving on to the national arena. Advocates of decentralisation argue that it opens up avenues for women to articulate their interests, to enter arenas of political decision-making, and to advance women interests. However, our analysis shows that women representation in local government does not guarantee that they will have any substantial influence over policy decisions, or that they will articulate women’s interests. It depends on the incentives facing them as representatives, and it requires a conscious and deliberate action on the part of the women to make a difference. It also requires effective knowledge and understanding of how the system works.

There is a persistent low level of women representation at the local level in Malawi. Only 13.4 per cent of the local councillors elected in 2014 were women. Local councils were established only in 1994, thus, there is also a very limited experience with local government. There is also little empirical knowledge on the effects of women representation of in local government councils in Malawi: whether women have influence and whether women are able to use the arena and to use if to articulate women’s interests.

This brief is based on an empirical study of three dimensions of women’s representation:

- The political motivations of women councillors elected in the 2014 local elections

- Perceived space for participation in local councils

- Ability and motivation to use the arena to articulate women’s interests in particular, thus whether they act as representations for women.

Councillors’ motivations for standing as political representatives, and their abilities to articulate issues, are important indications of whether they perceive themselves as representatives for women and thus ‘act for women’ (articulate women’s interests).

The analysis in this brief draws mainly on quantitative council representation data. The data was collected from all the 34 local councils in Malawi, and covers survey data from 51 women councillors (representing 91 per cent of all women councillors in Malawi) and qualitative discussions (group and individual interviews) that we held with a selection of both women councillors and council secretariat staff.

The Numbers of Women in Local Government

Since Malawi adopted decentralisation in 1998, the representation of women in local councils has been minimal. In the first local government elections that took place in 2000, women were successful only in 70 out of the 861 wards across Malawi, depicting an overall 8.1 per cent women representation.

After this, local government elections were consistently postponed. The second local elections took place after six years, in 2000. When their term of office expired in 2005, no councils were in place for nine years until the ‘tripartite’ (presidential, parliamentary and local) elections in May 2014.

Since Malawi adopted decentralisation in 1998, the representation of women in local councils has been minimal.

The re-introduction of local government councils in 2014 gave hope that it would increase the participation of women in local politics. Out of the 2412 councillor candidates standing for the 2014 local elections, there were 419 women (17.4 per cent). Most of the candidates who stood were from People’s Party (PP), followed by the United Democratic Front (UDF), independents, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Malawi Congress Party (MCP).

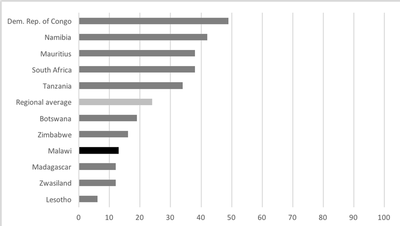

The result of the local election was that 56 of the 419 elected councillors were women (13.4 per cent). This was a remarkably lower figure than the number of women presented for election, and it led only to a marginal increase in women representation in local government. The figure also implies that Malawian women’s representation in local government is below the SADC average, which is at 24 per cent. Figure 1, which compares Malawi with the other SADC countries in terms of percentages of women in local councils, illustrates this point very well.

Figure 1: Representation of Women in Local Government in SADC (2014)

Source: Gender Links 2014 and MEC Election Results 2014

Women’s Motivations for Standing as Local Councillors

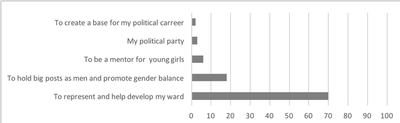

In our survey, we asked the women councillors about their motivation for running for office and their ambitions on what they wanted to achieve.

Figure 2 shows that the majority of the women councillors (70 per cent) explicitly their primary motivation was to address the development needs of their constituency. None of the women explicitly talked about advancement of women’s interests or attention to women’s needs as part of their primary motivation, although a small group was motivated to stand in order to ensure gender balance in representation and to serve as role models for girls.

Figure 2: What motivated you to stand as a Ward Councillor?

Source: Female Councillors Survey, 2015.

Women’s motivation is related more to generic interests than to particular group interests. Once in power, their behaviour is influenced by what they think will boost their chances of re-election. This is also in line with what Cammack and O’Neil (2014: 67) described as the most visible effect of competitive clientelism in Malawi: the incentives of political leaders (whether men or women) is to directly “deliver development” to their constituents, which is also necessary for re-election.

However, in our qualitative discussions, we also wanted to identify the key challenges for the ward, and it is worth noting that some women talked about issues that fall within the sphere of women’s interests, such as early marriages and wife abandonment, lack of income generating activities for women, low literacy levels for women, and limited access to portable water. This suggests that even when the primary motivation appears to be for the ward, women councillors include gender issues within the category of the ward’s key problems, and as such, these issues stand a chance of being given attention.

Women’s Positioning in Council Leadership

About 7 per cent of the local government council chairpersons are women, and 40 per cent of the vice-chairpersons are women. The very high number of women vice-chairpersons can probably be attributed to many council secretariats’ efforts to promote a certain gender balance in key decision-making positions. However, while the proportion of women vice-chairpersons is relatively high, when interviewed most of the women vice-chairpersons were unclear about what the office actually entails, and what their role is in it. Female ward councillors in a group discussion expressed the understanding that:

“We need to say the truth; we do not know the role of the vice chairperson in these committees. Before each council meeting the DC always call the chairperson of the council for briefing, but he does not call us vice chairpersons. Yet when we are in the council meeting we are just told to sit with them as if we are a handbag.”

Similar sentiments were also echoed by other women councillors, with the following:

“We are wondering what are the actual roles of vice chairpersons in these council committees because the male chairpersons tend to dominate everything. When this happens, it makes us women councillors to look like fools or that we are incompetent. We really need help.”

These stories also illustrate some tactical side-lining of women. Although one problem is the lack of a well-defined role for the two actors (chairpersons and vice chairpersons), we believe another problem is the council chairpersons’ personalities and (lack of) willingness to delegate. The various documents that guide the work of the local councils only stipulate that a vice-chairperson is supposed to stand in when the chairperson is not present. This assumes that when the chairperson is absent, he (or she) has to find it necessary and be willing to provide space for the vice-chairperson and to delegate some tasks.

We found, from our interviews, that the chairperson rarely decides to delegate, that the actual involvement of vice chairpersons is very low, and for the most part the women vice-chairpersons are simply figureheads. They do not know how to steer meetings and deliberations. This constrains the ability of the women vice-chairpersons to gain exposure and experience as leaders in local government, let alone gain the confidence and agency to use their leadership position to articulate and advance issues of interest, be they ward interests or women specific interests.

A pictorial view of a full Local Council meeting. Source: Nyasa Times

Women’s positioning in Council Service Committees

In addition to the full (local) council, the council’s service committees play an important role in local governance, as they can propose activities in any sector, examine policies, and oversee their implementation. The service committees are important avenues where women interests can be articulated and discussed.

While the overall number of women elected in the councils is low, women representation in some council service committees is rather high. Over 60 per cent of the women representatives is serving in two or more council service committees. Besides, about 33 per cent of the chairpersons and 25 per cent of the vice-chairpersons of the various service committees are women. This is a positive sign, and indicates that local government may function as a ‘school of democracy’ that involves women.

However, the challenge for many of the women representatives is how to effectively articulate issues (whatever they may be) in the various local governance structures, including in the service committees. The common statement that came out when interacting with the women councillors without a public service background was that “we don’t even know where to start from.” This is because most of them do not really know what they are supposed to be doing, they have not fully grasped the operations of the council or the service committees, and they are not able to understand and articulate the issues in the English language. In a discussion with women councillors who were attending an orientation meeting in the central region they told us that

“Yes, we were elected into various council committees but the problem is that we do not really know how the council works and are unable to articulate issues and even critically analyse issues... As a result, most of us are not taken seriously when we are speaking at the council level. Because we do not really know the issues, we are afraid of speaking, lest we speak things that do not make sense.”

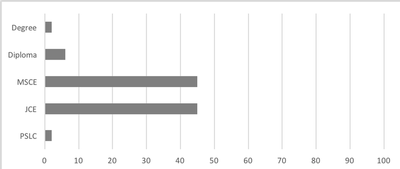

The majority of the councillors are also new and inexperienced in matters of local government. Prior to becoming councillors, most of the women served as businesspersons (44 per cent), others as subsistence farmers (25 per cent), and primary school teachers (11 per cent). Some key informants attributed the councillors’ limited understanding and knowledge to their low education levels (which is lower than men’s education level in Malawi), which does not match the level of understanding and skills required for policy deliberation and responsibilities.

This goes back to the law that guides entry into local government. The Local Government Elections Act of 1996 does not prescribe any specific educational qualifications, but it requires that candidates should be able to read and write English. This has been a subject of much debate in local discussions on the potential of women councillors in Malawi, because in general women are less educated and less able to use English.

The actual education profile of the women councillors, as depicted in figure 3 below, shows that almost one half (45 per cent) of the women councillors possess a Junior Certificate of Education (JCE; which entails two years of secondary school), while the other half (45 per cent) holds a Malawi School Certificate of Education (MSCE; the secondary school exam). This is a low to intermediary education. Another 6 per cent holds a university diploma and 2 per cent a university degree, but only two percent has nothing but a PSLC (the Primary School Leaving Certificate).

Figure 3: What was your highest qualification before becoming a ward councillor?

Source: Women Councillors Survey, 2015.

The women councillors also lack basic information about their council, and the flow of vital information from the council staff to councillors is limited. There have been a widespread perception among councillors that council administrative staff is deliberately withholding vital information, not facilitating the holding of regular service committee meetings (under the pretext of lack of resources etc.), in order to restrict the capacity of the councillors to oversee and scrutinise the officers’ activities. In addition, very few women possessed basic documents guiding the working of a council, such as the Local Government Act, Decentralisation Policy, the Constitution, and the various council guidelines. In some areas, CSOs have been supporting councillor training and providing copies of guidebooks on local government and on the conduct of council business, but councillors, and especially women councillors, are not able to fully grasp the content because almost all are in English. These challenges have a huge bearing on the potential of women councillors to advance issues and to influence the outcomes of the local decision-making processes.

Policy Implications

This brief demonstrates that a forceful impediment for the substantive representation of women in Local Government Councils in Malawi is to overcome the embedded challenges surrounding political incentives, technical knowledge, and power that are undermining the linguistic and epistemic authority of these minority actors in the Councils. Bridging these challenges through mentoring or coaching offers a promise of enhancing the possibilities of substantive representation in local governments. Thus, policies and programmes aimed at improving gender equality in local governance should not only aim at increasing women’s representation in terms of numbers, but they should also build women’s political leadership capacities, train women in ‘how things work’, and build a network of social and political relationships in order to be effective.

Formation of Women Councillors Caucus by Malawi Local Government Association is one way of supporting women’s capacity for effective participation.

Source: Malawi Local Government Association

![Corona überleben: Die Figur der:s Überlebende:n als Trägerin von Hoffnung und Angst in den Politiken einer Krise im Werden [Surviving Corona: The figure of the survivor as bearer of hope and fear in the politics of an emerging crisis]](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/18259-Corona-und-mediale-ffentlichkeiten.png)