Breaking BAD: Understanding Backlash Against Democracy in Africa

The nature of democratic backlash: Democratic rights eroding from within

Measuring democracy in Africa- what does the data say?

International responses to democratic backlash

How to cite this publication:

Lise Rakner (2018). Breaking BAD: Understanding Backlash Against Democracy in Africa. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2018:3)

There is a trend of democratic retrenchment across the African continent. Despite democratic gains in some states, the overall tendency over the past decade has been the erosion of democratic gains won in the period after 1990. Democracy is challenged in ways that pose threats to freedom of speech, association and information, the ability to choose political leaders, rule of law with recourse to independent courts, protection of personal integrity and private life. This CMI Insight discusses the ambiguous and multifaceted features of democratic backlash in Africa, and responses from international and domestic actors.

African states have adopted legal restrictions on key civil and political rights that form the basis of democratic rule in a range of countries from dominant party regimes, such as Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania, to competitive electoral democracies, like Zambia, Senegal and Malawi. In South Africa, where democracy and rule of law appear deeply institutionalised, the succession battles and exposed levels of corruption under President Zuma, who was recently removed from the leadership of the ANC party, suggest a weakening of the institutions intended to check executive powers. The court annulment of the Kenyan elections of September 2017 suggests that the courts were able perform an important accountability function and safeguard free and fair election. However, the aftermath of the Kenyan elections culminated with President Uhuru Kenyatta closing TV and radio stations in early 2018.

This slow, piecemeal erosion of democracy from within means that it is exceedingly hard to pinpoint exactly when a political system transforms from one regime form to another.

Civil society actors, policy makers and scholars warn against the democratic backlash and its negative implications for domestic and international politics. Internationally, the African democratic backlash challenges global actors who have long pressured developing countries to politically liberalise. Yet, following what appears to be a global trend of democratic backsliding, space for international influence and the spread of liberal norms is closing rapidly. Domestically, the observed backlash against democracy may pose further social and political threats with wide-reaching implications for development. This may, in turn, challenge the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Rukanova and colleagues (2017) argue that whereas closing space for civil society impacts on voice and participation first and foremost, restrictions on civil society ultimately may curb even the most seemingly apolitical activities such as humanitarian relief.

The nature of democratic backlash: Democratic rights eroding from within

It is important to note that the current backlash against democracy differs from previous periods of democratic retrenchment. Contemporary processes of democratic backlash are slower in pace: now, democracies tend to erode and not break. In the 1970s, democratic breakdowns tended to result in abrupt military or one-party regime shifts (Bermeo 2016). This is no longer the case. Since the end of the cold war, almost 90 per cent of all countries in the world hold regular and at least minimally competitive elections. Yet, increasingly, we witness elections held under authoritarian conditions and incumbents manipulating the electoral process with no intention of succumbing their rule to electoral uncertainty and competition. Across the African continent, incumbent leaders resort to illiberal strategies to win elections, including election violence, vote-buying, voter intimidation, and media control. Yet, while observers lament that the quality of elections is eroding, multiparty elections are upheld, with regular intervals, across the continent.

A second distinctive feature characterising the contemporary democratic backlash is that it is primarily targeted at some institutions and some aspects of liberal democracy. Some democratic institutions are deliberately dismantled through legal and budgetary procedures, but other institutions may be thriving. Multiparty elections have become a regularised feature, yet democratically elected parliaments pass votes curtailing the independence of courts or electoral institutions intended to secure accountability in future electoral contests. Legal restrictions imposed on civil society groups in many countries are targeted only at some organisations, such as human rights organisations (Christensen and Weinstein 2013, Dupuy et al. 2016). Churches, trade union groups and other interest groups are typically not targeted by the new legal and financial restrictions. The incremental forms of backsliding also create political challenges as incremental changes such as alterations to electoral laws and voter registration procedures rarely mobilise mass protests. Similarly, media restrictions, court manipulation and restrictions on NGO funding may only generate fragmented opposition.

Finally, and closely linked to the points above, a central feature of the ongoing backlash against democracy is that the undoing of a set of democratic rights and the institutions upholding it are legitimised through democratic institutions that often marshal broad popular support. This slow, piecemeal erosion of democracy from within means that it is exceedingly hard to pinpoint exactly when a political system transforms from one regime form to another. This again challenges our understanding of the processes witnessed conceptually, methodologically and theoretically (Waldner and Lust 2018, Bermeo 2016). This again raises critical questions, like how do we know when a democracy is no longer a democracy? When do a regime change from one form to another?

Measuring democracy in Africa- what does the data say?

Is there evidence of a global democratic backlash? The answer, unfortunately, is yes. According to the Freedom House report, Freedom in the World 2018 Democracy in Crisis, 2017 marked the 12th consecutive year of a global decline of democracy. The global average level of democracy has slipped back to where it was before the year 2000. The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset which measures democracy along seven principles of democracy supports the overall trend reported by Freedom House, However, they also report that on average, the decline has been moderate, and most changes have occurred within regime categories—with democracies becoming less liberal and autocracies less competitive and more repressive. So far, at least, the data reports relatively few countries backsliding from democracy all the way to full-blown autocracy. Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) is another index measuring the status of democracy. Their democracy index is constructed on five key measures of democracy: Elections and pluralism, citizen rights, governance, political participation and political culture, measuring democracy on a scale from 0 (autocracy) to 10 (full democracy).

According to the EIU democracy index, the African “mean score” has increased in this past decade from 4.11 to 4.28, yet below the global mean score at 5.52. The worrying trend is that the improvements happened in the period 2006-2011 and since progress has stagnated. Moreover, the data suggests significant regional differences. The most distinct democratic improvements have taken place in North and West Africa. Of the ten countries in Africa where democracy has markedly decline according to the five-point democracy index, four are East African countries: Ethiopia, Sudan, Rwanda and Burundi. In more than half the countries on the continent however, the process of democracy is characterised by stagnation. This is also the main conclusion in Bleck and van de Walle´s recent analysis of African elections (2018). According to these authors, a striking characteristic of the region that needs explaining is how little negative or positive regime change that has actually taken place since the conclusion of the democratic transitions of the mid-1990s. In the African context, when countries start holding regular multi-party elections, they largely continue to do so. Military coups that used to lead to lengthy periods of non-electoral politics, now get overturned quickly, because of both local and international pressures, and regular elections have become the default option of politics. This paradoxical continuity observed since the end of the transitions of the 1990s shows that the authoritarian reflexes in the executive have not changed markedly and the composition of the political class remains very similar: Indeed, in a youthful continent, the political class seems to continue to be getting older (Bleck and van de Walle, 2018).

International responses to democratic backlash

Puzzlingly, the ongoing backlash against democracy appears heavily concentrated in countries that made distinctly democratic gains in the 1990s (van de Walle 2016). African countries have traditionally been the recipient of high amounts of foreign aid, and as a result, benefited heavily from good governance support after the end of the Cold War at a time when the West had few competing interests. In the 1990s and 2000s, democracy assistance support resulted in a continent-wide growth of civil society organisations, the spread of basic human rights, and several successful national democratic transitions. Scholars and donors alike have spent a great deal of effort to study the institutionalisation of democratic rule on the African continent (Bratton & van de Walle 1997, Cheeseman 2015, Bleck and van de Walle 2018). Now, however, scholars, pundits and policymakers alike are struggling to explain the reverse: the ongoing backlash against democratic rule in Africa and how the international community can respond and counteract the ongoing erosion of democracy. But, responses from the international actors are challenged by the nature of the democratic backsliding. Incumbent governments employ formal democratic institutions and institutional mechanisms, set up with the support of the international community, in their attempt to roll back democracy, such as handsome majorities in the legislature won through electoral processes in part financed by international aid donors. The international community do not know how to respond to this trend (Bush 2015, Dietrich and Wright 2015), in part, because it is difficult to assess precisely when, how and which elements of democracy are eroding.

The international community does not know how to respond to democratic backsliding in part, because it is difficult to assess precisely when, how and which elements of democracy are eroding.

Arguably, international donors have performed relatively well in promoting and financing democratic institutions through engaging governments and power-holders. But governance assistance have been less successful in terms of identifying and assisting ‘change agents’ outside government (Banks, Hulme, & Edwards 2015, Breen 2015). African governments are increasingly imposing restrictions on foreign funding to NGOs and civil society associations, leaving international donors with fewer options as support to human rights and democracy traditionally has been channelled through NGOs either directly or through transnational NGOs. With this door gradually closing, the only other door open to international support is through governments, the international community is increasingly finding itself in a situation where their remaining “tools” to promote democracy appear to support the increasingly more autocratic tendencies of African executives.

Emphasising the global character of the ongoing “democratic backsliding”, arguably, political leaders no longer feel the need to “make excuses” or pretend to adhere to democratic institutions and liberal norms. Similar arguments may be made about the international community. Based on the positive economic results and progress on some key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by some of Africa’s authoritarian, dominant party states like Ethiopia and Rwanda, parts of the aid community now appear to question the validity and legitimacy of adherence to democracy being a condition for developing assistance (Kelsall and Booth 2013). Observers now argue that competitive elections pose special dangers in low-income, poorly institutionalised political systems (Ibid).

Responses to democratic backlash from civil society

African civil society associations are now facing a “double jeopardy.” They need increasing support from the international community to combat the retrenchment of democratic rights by their governments. Yet, due to governments imposing legal restrictions of NGOs receiving foreign funding, the same organisations are receiving less attention and financial support from the international community. As a result, both domestic civil society actors and international supporters are searching for new solutions. A number of recent studies and evaluations highlight the challenges posed by the “closing space for civil society engagement” (Brechenmacher 2017, Mendelson 2015, Rukanova et al. 2017).

Rukanova and colleagues (2017) shed light on the ‘adaptation and mitigation’ approach that most international philanthropic foundations and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) are adapting, hoping to create a distance between the humanitarian actors and the more outspoken spectrum of development and human rights actors (Rukanova et al. 2017). Harding (2015) points to a distinct shift in the “profiling” of NGO, either towards a stronger human rights (or protest) framing or a development framing, where civil society organisations increasingly shy away from focusing on governance issues in order to continue to operate without government interference. Increasingly, however, there is reason to expect that African civil society organisations aiming to advance human rights and good governance now have to operate “from below,” that is, through grassroots networks of activists who form local civil society groups, non-governmental organisations, or social movements focused on the protection of civil liberties. Because such work ultimately challenges the legitimacy of governments that carry out repression, human rights activists, including lawyers, journalists, and academics, are themselves often targeted for politically motivated trials or violent persecution by government agents (CIVICUS 2016).

Breaking Bad: Understanding Backlash Against Democracy in Africa

This research project, funded by the Norwegian Research Council (2018-2021), focuses on the conscious efforts of political actors and elites to curtail democratic rights along four interlinked dimensions of democracy. We further analyse variance along these four dimensions of rights and responses from domestic and international actors.

Participation rights enable access to decision-making and include rights to form, join, support, and operate political parties and civil society organisations, and to meet and to organise mass events. African states are increasingly legally preventing civil society organisations from engaging in human rights work.

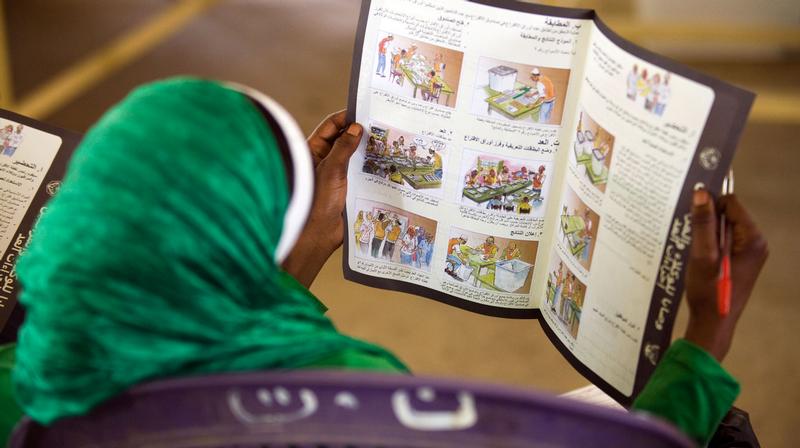

Contestation rights enable citizens to freely express their opinion on policy and to choose their political leaders and to monitor elections. Freedom of information and the press is under pressure in Africa. Governments enact laws preventing access to information and allow them to close both traditional and online media. Sham elections are on the rise in African states, with reigning political elites manipulating elections to maintain their hold on power. Election monitors are increasingly being harassed and legally barred from carrying out their functions.

Rule of law rights entail access to courts and equal and impartial treatment of all people by the law, which can be realised only under conditions of judicial independence. Recent years have seen serious regressions in judicial independence across Africa.

Personal integrity and gender equality rights entitle citizens to bodily integrity and a private sphere free from state interference, and to equality of opportunity: the ability to access all social, political, and economic spheres without discrimination – irrespective of sexual orientation and gender identity. Rights concerning gender equality, sexuality and reproduction have been severely limited in recent years with new restrictions on homosexuality, marriage, and abortion.

Where do we go from here?

Across the African continent, democracy is under pressure in ways that pose political and social threats. Citizens face mounting legal restrictions on freedoms of speech and association and are often subjected to the repression of peaceful protest. Governments perceive foreign aid to NGOs as supporting political opponents and a threat to their hold on power. Today, even the most basic of democratic achievements are being reversed, including in Africa’s more robust democracies like Zambia and South Africa (Gyimah-Boadi 2015). Institutions that were once crucial for promoting participation and fair contestation – such as courts, anti-corruption agencies and the media – are now under pressure and increasingly seen as being used as a part of an authoritarian toolkit. As a result, attention has turned away from explaining democratic transition and describing democratic consolidation towards specifying a democracy’s quality, identifying democracies’ hazard rates (the probability that they will decay), and explaining authoritarian persistence. Arguably, at the core of many democratic setbacks over the past decades, is the failure of institutionalisation – put differently, the capacity of many new democracies in the developing world has not kept pace with popular demands for democratic accountability. This piecemeal erosion of the democratic fabric of many African governments requires us to see democracy as a collection of multiple institutions and actors. Understanding the current backlash’s timing, manifestations, causes, and effects is not only of great scholarly importance, it also has significant policy relevance in a context where the international aid community is scaling back their support and the consequent potential for permanent, worldwide political regression.

While there are a number of recent studies and evaluations that highlight the challenges posed by the backlash of democracy in Africa, at present, we have a limited understanding of possible response mechanisms. How do activists come together to advocate for particular rights? When are activists more effective in generating mass citizen support for their campaigns? How can researchers, international actors and domestic civil society organisations work together to disseminate and use knowledge about organisational resilience in these circumstances? These will be pressing questions for scholars and activists going forward.

References

Banks, N. E. Hulme, D. Edward, 2015. “NGOs, States and Donors Revisited. Still too Close for Comfort?” World Development, Vol66, pp. 707-718.

Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding”. Journal of Democracy, 27(1): 5-19.

Bleck, Jamie and Nicolas van de Walle, 2018 (forthcoming): Electoral Politics in Africa since 1990. Continuity and Change. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Bratton, Michael, and Nicolas van de Walle. 1997. Democratic Experiences in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brechenmacher, S., 2017. Civil Society Under Assault: Repression and Responses in Russia, Egypt and Ethiopia. NY: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Bush, Sarah, 2015: The Taming of Democracy Assistance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carothers, Thomas. 2015. “The Closing Space Challenge: How Are Funders Responding?” Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Cheeseman, N., 2015: Democracy in Africa: Successes, Failures and the Struggle for Political Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Christensen, D., and J. M. Weinstein. 2013. “Defunding Dissent: Restrictions on Aid to NGOs”. Journal of Democracy, 24(2): 77-91.

Civicus. 2015. “State of Civil Society Report”. Johannesburg: Civicus.

Dietrich, Simone, and Joseph Wright. 2015. Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa. Journal of Politics, 77(1), 216-234.

Dupuy, Kendra, James Ron, and Aseem Prakash. 2016. “Hands Off My Regime! Governments’ Restrictions on Foreign Aid to Non-Governmental Organizations”. World Development, 84: 299-311.

Gyimah-Boadi, E. 2015. “Africa’s Waning Democratic Commitment”. Journal of Democracy, 26(1): 101-113.

Harding, L. 2015: Protecting Human Rights and Development Actors. York: University of York Centre for Applied Human Rights. Working Paper No. 1.

Helle, Svein Erik and L. Rakner (2017), “The impact of elections. The case of Uganda”, in Johannes Gerschewski and Christoph Stefes (eds.). Crisis in Autocratic Regimes, Boulder: Lynne Rienner, pp. 111-134.

Kelsall, T. and D. Booth, 2013: Business, Politics, and the State in Africa: Challenging the Orthodoxies of Growth and Transformation. London. Zed Books.

Levitsky, S. and L. Way, 2015: “The myth of democratic recession”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 45-58.

Mendelson, S.E., 2015. Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can be Done in Response: A New Agenda. Washington: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Rukanova, S., R. Herweijer, R. Kerkhoven, H. Surmatz, D. Doane, 2017. Why Shrinking Civil Society Space Matters in International Development and Humanitarian Action. European Foundation Centre and Funders Initiative for Civil Society.

Van de Walle, N., 2016: “Two cheers for African democracy”, in Muna Ndulo and Mamoudou Gazibo, (eds). Growing Democracy: Elections, Accountability, and Democratic Governance in Africa, (Cambridge UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2016). pp. 304-312.

Waldner D. and El Lust (2018). Unwelcome Change. Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding. Annual Review of Political Science. Forthcoming.

Wood, Ngaire. 2008. “Whose Aid? Whose Influence? China, Emerging Donors and the Silent Revolution in Development Assistance”. International Affairs, 84(6): 1205-1221.

Photo by:

Lise Rakner

![Corona überleben: Die Figur der:s Überlebende:n als Trägerin von Hoffnung und Angst in den Politiken einer Krise im Werden [Surviving Corona: The figure of the survivor as bearer of hope and fear in the politics of an emerging crisis]](http://www.cmi.no/img/400/18259-Corona-und-mediale-ffentlichkeiten.png)