Candidate selection and informal soft quotas for women: Insights from Zambia

Women’s entry into politics in Zambia

Parties and gendered candidate selection

Candidate selection and gender imbalance in Zambia

How to cite this publication:

Vibeke Wang, Ragnhild L. Muriaas (2020). Candidate selection and informal soft quotas for women: Insights from Zambia. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2020:1)

What does it take for a female politician to win a party nomination? We still know little about women’s entry into politics in countries without formal gender quotas. Using data from Zambia, we argue that both in emerging and established democracies, centralized nomination processes both enable and disable women in contexts where gender quotas are not adopted. Informal institutions rarely benefit women more than men. Informal soft quotas may even act as glass ceilings that prevent women from being nominated, because party leaders rarely go beyond the informal quota threshold.

This CMI Brief is based on the article “Candidate selection and informal soft quotas for women: Gender imbalance in political recruitment in Zambia” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7 (2): 401–411.

Women’s entry into politics in Zambia

Zambia is an emerging democracy and has a candidate-centered electoral system. The main political parties leave it to local party members to identify aspirants, i.e. those who want to become candidates, and to come up with recommendations to the national leadership who then select and decide on candidates. These procedures result in a selection process which suffers from a lack of transparency and represents a high financial risk for aspiring candidates. They must provide payments, bribes, food, and transportation to show off their resources and popularity, even though their successful efforts at the local level might have no bearing on the central party leader’s final nomination decision. According to formal party rules, local leaders’ recommendations are not binding. Party leaders have the final say in any decision about candidacies.

In Zambia, the combination of strong party leaders and demands for primaries from local communities produces noteworthy effects. Although the local party branches would like to see their recommendations being followed, primaries also serve an additional purpose. The local-level candidate nomination processes represent an opportunity for local party members to benefit from their party loyalty. Aspirants must provide payments, bribes, food, and transportation to show off their resources and popularity, even though their successful efforts at the local level might have no bearing on the central party leader’s final nomination decision. Although the local candidate selection process could be seen as a necessary ritual for candidates, time and time again it is demonstrated that a good bargain with the party leader may be the only critical key to coming out as a top nominee. During the selection process, many female aspirants run their campaign on false hopes that focus on convincing the local leaders, but often the selected few who end up being nominated as candidates win their selection through a bargain with the central party leader, not through the support of their local committees.

Yet in this context, and without any formal quotas for women in politics, the major political parties in Zambia over the past two general elections have nominated exactly the same number of female candidates, although, on average, women represented only 14 percent of members of parliament (MPs) in Zambia from 1996 to 2016. Rules for selecting candidates are becoming increasingly formalized, while the requirement to nominate a certain number of women remains informal.

To shed light on the puzzle of how women have gained party nominations in Zambia, we ask the following questions: How do formal selection procedures and an informal requirement of nominating a fixed number of women interact in Zambia’s political parties? What effect does centralized decision-making power have on women’s motivation to win a nomination when they have to compete in costly non-decisive primaries at the local level?

We carried out a field study in Lusaka, Zambia, in June and July 2015. In all, we conducted 41 semi-structured interviews with MPs, representatives of women’s organizations, secretaries of political parties, government officials, international donors, and academic consultants. During these interviews, we explored the role of party leadership in the political recruitment process, as well as which factors local selectorates (that is, members of local party committees responsible for recommending candidates) prioritize when they identify their preferred candidates. Through both conversations and carefully selected questions from an interview guide, we identified some of the crucial mechanisms at play when candidates are nominated to stand on a party ticket.

Parties and gendered candidate selection

Within the recent politics and gender scholarship, an emerging literature addresses how the degree of party centralization and inclusiveness affects the likelihood of women being selected. The literature on formal selection rules is however inconclusive – some studies argue that inclusive, decentralized decision-making is most favorable to women, while others provide examples of why an exclusive, centralized process is more effective in correcting gender imbalance in candidate selection.

Centralization may help enforce an informal “soft quota” that guarantees that at least a fixed number of women are nominated, despite male-dominated local party branches and a commercialized selection process. Yet an informal soft quota, in centralized candidate selection systems that includes an aspect of localism, may also lead to less transparent processes and legitimize other informal avenues in order to strike a good deal with the central party leader. Consequently, centralized decisions drive informality, and as argued by Bjarnegård, informal institutions rarely benefit women more than men.

Candidate selection and gender imbalance in Zambia

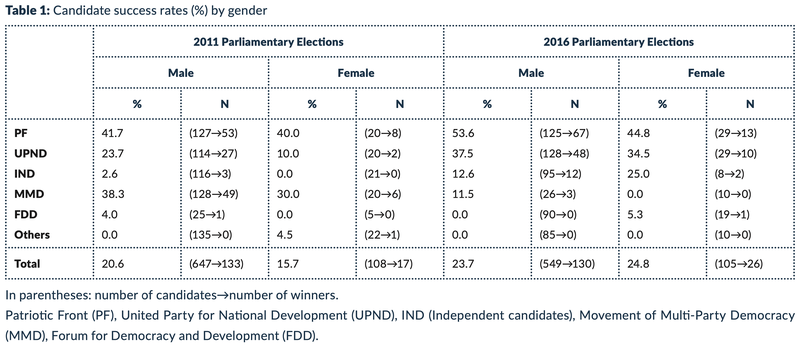

The major parties remain highly centralized and the ruling party prefers to build coalitions with individual opposition MPs rather than negotiating with opposition parties. Party loyalty is thus minimal due to constant party switching. Within this context, gender balance in political recruitment has remained low. Table 1 shows a striking pattern between the nomination of female candidates in the 2011 and 2016 elections. In 2011, the three main political parties were Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD), Patriotic Front (PF), and the United Party for National Development (UPND), and each party nominated 20 female candidates.

In 2016, there were only two main parties contesting, since MMD dismantled after PF won the 2011 presidential elections. The outcome of the selection process was that PF and UPND nominated 29 female candidates each (see table 1). If the similarity in female candidates nominated by key parties is not coincidental, but an understanding agreed upon by party leaders, we see the contours of an informal soft quota for women. If so, the enforcement of the agreement is made possible due to the centralized decision-making power of party leaders during the selection processes.

Centralization: Soft party quotas, but hard glass ceilings

The Zambian case clearly illustrates this point, but highlights that centralized party decisions can be both enabling as well as disabling for female aspirants. Centralization is enabling because, regardless of how the rest of the selection process plays out, the party leader can select a woman if he or she so wants, and can even enforce a soft quota that establishes a fixed number of female candidates. A soft quota aims to increase women’s representation indirectly through internal party quotas or more directly through informal targets and recommendations. Yet centralization can also be disabling if soft quotas create a glass ceiling because party leaders informally and secretly collude to decide that only a set number of women will go through.

In this system, at least three factors make it difficult for women candidates to succeed in becoming the favored candidate at the local party branch level, according to a representative from the Center for Intra-party Dialogue (as well as others we interviewed). First, the composition of nominating committees affects gender balance; “women are disadvantaged because they [nominating committees] are heavily male populated. There are so many men. So the chances of men thinking about a woman is very small.” Second, the male selectorate has a very specific image of homo politicus: “Parties are patriarchal, they have the image of a father figure, the father of the party.” Third, women have a difficult time accessing the money that play an important role in Zambian politics: “Women are economically disempowered in this part of the world. They are not financially prepared to have the kind of campaign that brings victory. You know, Zambian elections are highly commercialized, mostly it is the men that have that resources to give to the party to do elections”.

The importance of sufficient finances was highlighted in all the interviews with both successful and unsuccessful candidates, as well as with members of international and domestic NGOs in Zambia. One female MP explained, “In Zambia, the system is such that the parties have to finance their own candidates, but the parties don’t have money. So at the end of the day, it is the individual candidates that finance their own elections.” She continued by giving an example of how candidates go about convincing the local selectorate about their merits: “The male aspirants say, ‘I can bring in vehicles, I’m going to put in maybe the equivalent of 20,000 dollars,’ and then the women say, ‘I can put in 2,000 dollars.’ So the parties get discouraged”.

Not only the elections themselves, but also the grassroots selection processes within political parties (particularly in party strongholds) are very expensive. According to a news source, the UPND aspirants in some constituency primaries gave up to K500 (US$52) to each member of the selectorate to be placed at the top of the recommendation list. A representative of the Zambia National Women’s Lobby also highlighted the issue of money when she commented on the corrupt selectorate, “The ones that have paid the most are the ones that they normally adopt [nominate]”.

Centralization could thus be seen as a remedy against the negative gendered effects of commercialized nomination processes, male-dominated selectorates, and gendered stereotypes about a father-like “ideal” candidate. Yet a party leader’s centralized powers can also disadvantage women. Participation in localized selection processes can clearly be discouraging, but some women can be well-known in their communities and have support from influential local leaders, although they have never been in a position where they have to negotiate with the party leadership in the capital. In a centralized nomination system, aspirants participate in several rallies and are interviewed at different stages, but may end up not winning the nomination, even if they are the most popular person at the local level. As one female parliamentarian explained, “Well, it’s the corruption, you have to pay some people to support you… But there is not so much transparency, so in the constituency you come out as number one, in the district number five… There is this fluctuation. There is no consistency”. Since the central party leader can overrule the recommendations of local party branches, the local selection process is in danger of being reduced to keeping local party branch members happy by giving them food, sugar, transport, or cash, without knowing if these personal outlays will lead to personal success.

Under current candidate selection systems in Zambia, aspirants cannot know based on their experience at the local level whether they will be nominated. The final result of the selection process is announced when the nomination list is submitted to the national electoral commission by the party leader. Until then, it is unclear whether recommendations given at the subnational level will be followed. For example, the national leadership of United Party for National Development ignored local level protests when it selected Patricia Mwashingwele as a candidate in Katuba constituency, even though the primary was won by a man. By contrast, a well-known women’s rights activist was led to believe that she was ranked as the favorite by all subnational branch selection committees, but was turned down by the central committee, which picked a man. The combination of centralized decision making and a fairly inclusive system of local recommendation formation makes the nomination process costly and the outcome uncertain. Hence, what women potentially might gain from an informal soft quota deal among party leaders is lost by the discouragement of having to participate in primaries where local-level recommendations are not necessarily followed by the central party leadership.

Implications of findings

Indeed, centralized nomination processes make it possible for party leaders to enforce an informal soft quota that ensures that a certain number of women are nominated as candidates. Yet they are highly unlikely to go beyond the soft quota in nominating female candidates, even if there are more qualified women in the race.

Based on our study, we encourage more work on candidate selection in democratizing states without gender quotas, in particular, studies that focus on how political financing affects candidate selection. Zambia has hardly any formal regulations on party funding and no public funding. Perhaps political finance could be used as a tool to assist female aspirants in becoming candidates?

References

Bjarnegård, Elin. 2013. Gender, Informal Institutions and Political Recruitment: Explaining Male Dominance in Parliamentary Representation. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

Caul, Miki. 1999. “Women’s Representation in Parliament: The Role of Political Parties.” Party Politics 5 (1): 79–98. doi:10.1177/1354068899005001005.

Daily Nation. 2016. “Katuba protestors storm HH’s home.” May 30. https://zambiadailynation.com/2016/05/30/katuba-protestors-storm-hhs-home/

Hinojosa, Magda. 2012. Selecting Women, Electing Women: Political Representation and Candidate Selection in Latin America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Ichino, Nahomi, and Noah L. Nathan. 2012. “Primaries on Demand? Intra-party Politics and Nominations in Ghana.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (4): 769–791. doi:10.1017/S0007123412000014.

Kenny, Meryl. 2013. Gender and Political Recruitment: Theorizing Institutional Change. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kenny, Meryl, and Tànya Verge. 2013. “Decentralization, Political Parties, and Women’s Representation: Evidence from Spain and Britain.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 43 (1): 109–128. doi:10.1093/publius/pjs023.

Krook, Mona Lena, Joni Lovenduski, and Judith Squires. 2009. “Gender Quotas and Models of Political Citizenship.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 781–803. doi:10.1017/S0007123409990123.

Lovenduski, Joni, and Pippa Norris. 1993. Gender and Party Politics. London: Sage.

Muriaas, Ragnhild L., Lise Rakner, and Ingvild Aagedal Skage. 2016. “Political Capital of Ruling Parties after Regime Change: Contrasting Successful Insurgencies to Peaceful Pro-democracy Movements.” Civil Wars. 18 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1080/13698249.2016.1205563.

Murray, Rainbow. 2010. Parties, Gender Quotas and Candidate Selection in France. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rahat, Gideon. 2007. “Candidate Selection: The Choice before the Choice.” Journal of Democracy 18 (1): 157–170. doi:10.1353/jod.2007.0014.