Save the Children’s work on child protection and child rights in Mozambique and South Sudan

Objectives and review questions

Child rights contexts and programme sites

Concluding observations and recommendations

Results and explanations of results

Recommendation 2: Make sure all key outcome variables are measured/reported.

How to cite this publication:

Matthew Gichohi, Ottar Mæstad (2023). Save the Children’s work on child protection and child rights in Mozambique and South Sudan. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report 2023:2)

Background

Save the Children Norway (SCN) and its partners are implementing an extensive programme to support children’s education, child protection and child rights in 16 countries. The programme is running from 2019 through 2023 and is funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad).

This review focuses on two of the three main programme areas – child protection and child rights – and on how Save the Children (SC) works to reach marginalised children within these programme areas. The third programme area – education – also has components related to child protection and child rights, but those aspects are not covered here.

The analysis and recommendations are based on data from two countries, Mozambique and South Sudan. The countries were selected because they represent child protection programmes with either a strong emphasis on child marriage and teenage pregnancy (Mozambique) or corporal punishment (South Sudan).

The review has been commissioned by Norad.

This review would not have been possible without the help several organizations and individuals. We would first like to extend our thanks to Wouter Vandenhole for acting as the quality assurance officer and providing excellent comments to the draft report. We would also like to thank all our interlocutors at Save the Children’s headquarters in Norway and in the field for shedding light on the efforts to improve children´s protections and fulfil their rights. In Mozambique these include: country office staff, PLASOC, Association Bvute re Rufaro, Girl Child Rights, ROSC and the 3R platform, CECAP, the National Human Rights Commission, the Child helpline, the Provincial Service on Social Issues in Manica, and the Chief Prosecutor for the Provincial Reference Group in Manica. In South Sudan: the Child Rights Coalition, the Human Rights Commissioner, Members of Parliament, Ministries of Gender Child and Social Welfare, Ministries of Education, The Organization Children´s Harmony, Disabled Agency for Rehabilitation and Development, Child Rights Network, Action for Development Foundation, and Jonglei Civil Society Network. We are also extremely grateful to community members, parents and children who took time to provide valuable insights into accrued program benefits.

Objectives and review questions

The objectives of the review are to:

- Assess the results achieved in the areas of child protection and child rights.

- Examine the extent to which SC manages to reach marginalized groups.

These objectives are met by answering the following questions:

- What changes have been observed in agreed outcome indicators? Have other important changes been observed?

- Which internal and external factors may have contributed to observed changes? How have challenges been addressed?

- Is the programme’s Theory of Change still valid? Is there any need to adapt/drop/add activities?

- How are marginalized groups included and their interests represented in the programme?

Marginalized groups are defined here as those who are discriminated against because of gender and/or disability. This is the definition applied by SCN in the programme under review.

Approach and methodology

This is a rapid review, primarily based on review of monitoring data and programme documents as well as key informant interviews during a 10-day visit to Mozambique and South Sudan. Rigorous data collection and analysis of the comprehensive programme at hand is hardly possible within such a short timeframe. Conclusions and recommendations should therefore be used with caution.

Data

Documents reviewed include the main programme document as well as results frameworks and annual and midterm reports from the study countries.

The quantitative data is fully based on monitoring data collected by SC and partners. The source data behind reported figures were reviewed and analysed to some extent.

The qualitative data was collected through interviews and focus group discussion with staff at SC country/regional offices, implementing partners, community members (community leaders, teachers, children, and parents), as well as government officials. The consultants decided which districts to visit, but due to time constraints the selection of communities and the organization of interviews was administered by SC and partners. Unfortunately, time did not permit triangulation with communities that had not benefited from SC’s programme.

In Mozambique, data collection took place in Maputo (capital), Chimoio (province capital) and in two communities in Manica district. Data collection in one additional community was cancelled due to security precautions when a cyclone hit the country. Interviews with ministries in Maputo were not implemented due to lack of response.

In South Sudan, data collection took place in Juba (national capital), Rumbek (Lakes State) and Bor (Jonglei State). Information was gathered through interviews with SC staff, implementing partners, and relevant line ministries, such as the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Gender, Child and Social Welfare in both states.

Analysis

Description and assessment of results. Analysis of the monitoring data is a straightforward before-after comparison. This exposes changes between baseline and midline but does not allow for causal attribution of results to programme activities.

We assessed factors that may have affected the reliability of the monitoring data, including the impacts of Covid on data collection, sample size, and sample composition.

Evidence of factors that may have contributed to change (or lack thereof) is obtained from both interviews and focus group discussions. Due to the high number of outcome variables assessed and the low number of interviewees and communities visited, we are only able to provide suggestive evidence of which factors may have contributed to or prevented change.

Validity of theory of change. We make separate assessments of the validity of the theory of change for each of the main outcomes. Due to the huge number of programme activities, we zoomed in on those activities that SC staff have identified as the most important and asked them to reflect on how these activities contribute to results. These reflections are used to analyze the validity of the theory of change. Due to time constraints, we have not been able to assess the scientific evidence base for the stated causal relations and their underlying assumptions.

Marginalized groups. We utilize participation data disaggregated by gender as an indicator of gender equality in SC’s programmes. When it comes to inclusion of children with disabilities, we rely mostly on unverified statements from interviewees, as very few monitoring data are disaggregated by disability status, and it is also unclear what participation rates would imply parity with other groups.

Ethics

An ethical protocol was developed as part of the inception report. Apart from the standard ethical guidelines for research, particular attention was paid to adhere to SCN’s ethical requirements for research with and on children.

Limitations

This review has several methodological limitations that need to be considered along with the analysis.

Review of results. Results data are largely based on before-after monitoring data. In general, we do not know whether observed changes in outcomes are due to SC’s programs or other factors, as we have not accessed data from relevant comparison groups. At the outcome level, our analysis is therefore more precisely described as an analysis of reported change rather than reported results. We have not been able to assess the quality of the monitoring data.

Our own qualitative data collection is from sites and respondents selected by SC and partners. We are unable to assess how representative they are.

Explanations. Explanations of changes obtained from qualitative interviews have to some extent been checked for consitency with reported output data. In many cases, we have had to rely on our oral sources only, mostly SC and partners. If their understandings are inaccurate, this review is likely to reproduce those inaccuracies.

Theory of change. SC programmes involve a large number of actitivies. It has been impossible within the time frame of this review to dig into the details of all these activites and assess whether the way they are implemented makes a significant contribution to the intended outcomes or not. For the same reason, there may be gaps that we have not been able to identify.

Marginalized groups. Very limited quantitative data has been available to analyze how well SC programmes target marginalised groups. Nor have we done separate data collection with marginalized groups such as children with disabilities.

Child rights contexts and programme sites

Mozambique

Child rights context

Mozambique is one of Africa’s poorest nations, with a GDP per capita of $500 in 2021 (World Bank 2022). The population is 33.3 million people, a significant portion of which is young: 52% are children under 18 years of age, while 23% are adolescents (UNICEF, 2020). 48% of Mozambican children live in absolute poverty, while 2 million children live without their parents (UNICEF, 2020).

Mozambique has taken several steps to increase access to education, including abolishing school fees, offering free textbooks, and investing in classroom construction. Despite these advances, about 1.2 million children are out of school and working. Many children do not complete primary school, which means that even fewer students enter secondary school. The most negatively affected groups are girls and children with disabilities (Save the Children Norad Framework Proposal, 2019).

Girls are often forced to leave school due to cultural pressures that require them to take care of younger siblings or sick family members or to get married. Mozambique used to have one of the highest child marriage prevalence rates in the world (49%) (AIS, 2015). Child marriage keeps girls out of schools, leading to a life of poverty, and leaving them vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse (Wodon, Q, et al., 2018). Child marriage is closely related to teenage pregnancies, which expose mother and child to increased health risks. In 2019, Mozambique passed a law criminalizing child marriage, but data are not yet available on how this has affected its prevalence.

Children with disabilities face social exclusion and stigma, but they also face educational systems and facilities that are unable to cater to their needs. It has been estimated that 14% of school-aged children have a disability and that 80% of disabled children are out of school (SIDA, 2014).

Mozambique ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1994 and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) in 1998. In 2007, Mozambique created the National Council on Children and a Children’s Parliament, in which children could reflect on their rights. Laws such as the Law on the Promotion and Protection of Children’s Rights and a Law on the Prevention and Combating of Human Trafficking have been passed, but enforcement of the laws is incomplete.

Programme sites and partners

The program is implemented in four districts – Manica, Machaze, Macossa, and Tambara – in the province of Manica. In addition, some programme activities are targeting national organizations and government bodies.

In Manica province, the program is implemented in partnership with four civil society organizations. Association Bvute re Rufaro, JOS-SOAL and GCR (Girl Child Rights) are implementing activities on child protection and adolescents’ sexual reproductive health, and PLASOC is implementing most of the child rights governance activities.

At the national level, three partners contribute to the two focus areas of this review. The Child’s Network (Rede da Crianca) is implementing advocacy activities on children’s rights and governance. ROSC (Network of civil society organization) in coordination with Save the Children are implementing advocacy activities on child protection, and Rede CAME (Network against child trafficking) in coordination with Save the children are implementing advocacy activities on child protection with a focus on combating child abuse.

South Sudan

Child rights context

South Sudan proclaimed its independence from Sudan in 2011 following twenty years of conflict. In 2013, however, civil war broke out and displaced over 2.2 million people (BBC News). In 2015, a peace deal was reached but fighting broke out again. In 2018, a new peace agreement was reached with the aim of setting up a government of national unity, but this process was postponed twice (The Independent, 2020). In February 2020, a peace deal was signed and a unity government comprising government and opposition leaders was formed (Human Rights Watch, 2020). As of 2023, South Sudan’s estimated population is 14.5 million, with a quarter of the population being between 15 and 29 years old, and more than two-fifths under the age of 15 (UNICEF, 2023). The country’s GDP/capita in 2016 was $1071.

Even though every child has the right to free education at the primary level (Ministry of Legal Affairs and Constitutional Development, 2009), more than two million children are out of school (UNICEF South Sudan, 2020). Lack of infrastructure, limited human resources, and insufficient teaching and learning materials, coupled with the massive disruption caused by the conflict, imply that not all children enter primary school and when they do enter, they are unsafe (UNICEF, 2020).

The largest group of out-of-school children are girls. Factors behind this situation are high levels of poverty, child marriage, and cultural and religious views that hinder girl’s education. Families with limited resources are more likely to send boys to school instead of girls because they see school as an investment. Older girls may leave school to be married, while some families may be reluctant for girls to walk long distances to school because of security concerns. Other parents do not send girls to school for fear they will get pregnant, as pregnancy and motherhood reduce bride price (UNICEF, 2020). Many South Sudanese communities see marriage as being in the best interests of girls and their families (UNICEF, 2020). Child marriage remains high in South Sudan; around 45% of girls in South Sudan are married before the age of 18 (UNICEF, 2019).

Only about 4% of children with disabilities in South Sudan attend school. There are not enough teachers trained to address special needs, and there is very little specialized equipment and few accessible school buildings (UNICEF, 2020). Children living on the streets are also very vulnerable to exploitation and violence. This places street children in a difficult position as they are unable to access vital services and are at risk of getting into conflict with the law. Since the crisis began, school-aged children have been displaced, often to areas without access to protected learning spaces or to host communities where education resources are non-existent or overstretched (UNICEF, 2020). Displacement increases the likelihood of sexual and gender-based violence.

South Sudan ratified the UNCRC in 2015, and its provisions were incorporated into national law through the South Sudan Child Act 2008 and Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan 2011 (The Child’s Rights Civil Society Coalition, 2016). The government also ratified other key international treaties aimed at protecting children from abuse and neglect, such as the Optional Protocols on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography and on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflicts (UN Treaty Body Database, 2020). South Sudan is, however, yet to ratify the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) (Oyet, 2021). South Sudan faces challenges in implementing and enforcing these laws due to a lack of resources and conflicts between customary and national laws.

Programme sites and partners

In South Sudan, program activities are implemented in Bor (Jonglei State), Rumbek (Lake States). The SC country office works closely with school administrators and various partner organizations at the community, state, and national levels. In Bor, the partnering organization is Action for Development Foundation (ACDF), while in Rumbek the partners are the Organization for Children’s Harmony (TOCH) and the Disabled Agency for Rehabilitation and Development (DARD). All these partners work across both Issue 2 (Child Protection) and Issue 3 (Child Rights Governance). At the national level, the country office works alongside the Child Rights Coalition (CRC), and the Ministries of Education, Justice, Gender and Social Welfare, and Health to improve child rights governance.

Findings

Child protection Mozambique

Objectives and activities

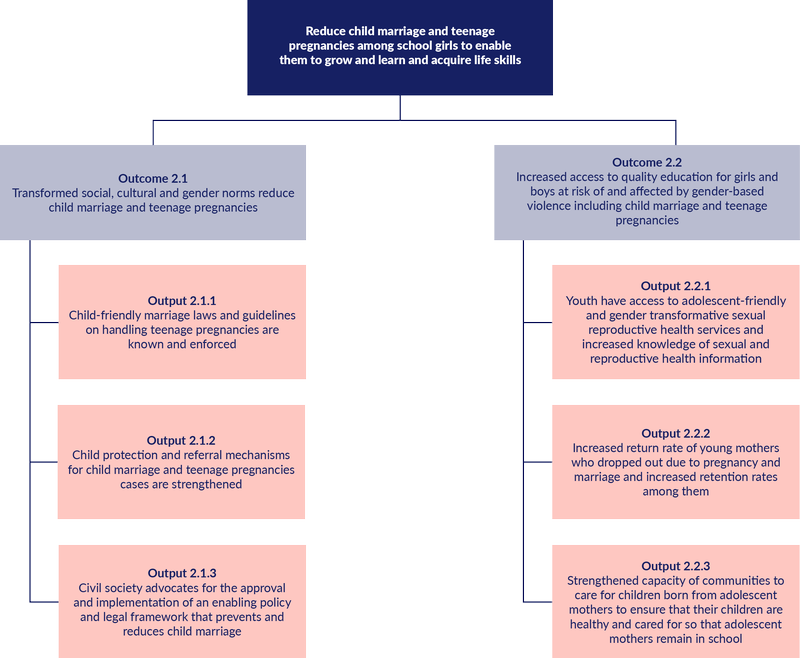

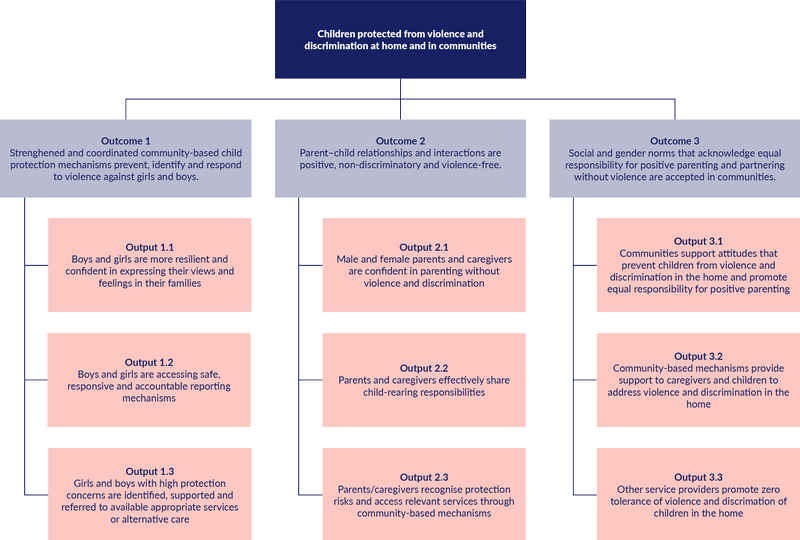

The objective is to reduce child marriage and teenage pregnancies among schoolgirls to enable them to grow and learn and acquire life skills. Intermediary outcomes are to 1) change norms related to child marriage, and 2) increase access to quality education for children who have been affected by gender-based violence, including child marriage and teenage pregnancies. Outcomes and outputs are summarized in the figure below. (Note: One additional outcome, related to children’s safety from violence in and around schools, was moved from the issue of education to the issue of child protection in late 2020. This outcome is not covered in this review.)

To change norms, community dialogues are conducted to disseminate information about the law that criminalizes child marriage and about the consequences of child marriage and teenage pregnancies. Engagement of community leaders is emphasized. There are also information campaigns, both at the community level and through mass media.

In addition, efforts are made to strengthen mechanisms for identification and reporting of child marriage and other cases of violence against children to the police and the social services. The Community Child Protection Committees (CCPCs) play an important role in identifying and reporting cases.

To increase access to education for children affected by gender-based violence, encouragement and support to get back to school are provided to girls who dropped out due to marriage and pregnancy. Sessions in sexual and reproductive health are offered to students at primary and secondary school.

Reported results

A law that criminalizes child marriage below the age of 18 was enacted in the fall of 2019. This is a major achievement for everyone who has promoted this reform over many years, including SC.

According to government officials, communities where SC and partners work are more aware of the law and how to report cases of violence against children than in other areas.

Data from the education authorities suggest that there has been a large reduction in the number of children who drop out of school, including reduced dropouts due to child marriage (see below).

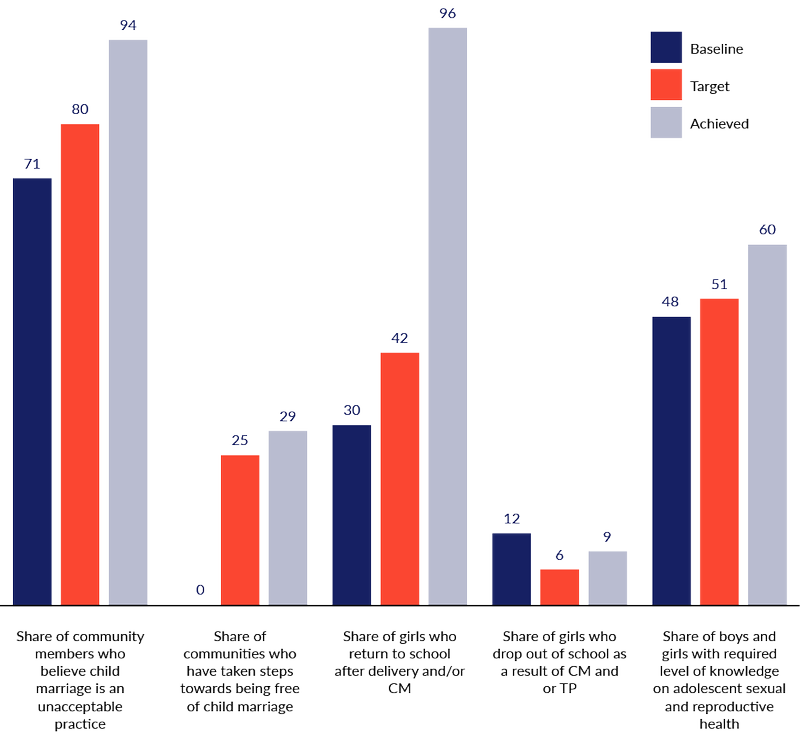

SC’s midterm report does not report on awareness of the law nor on the number of school dropouts, but five other indicators are reported (see diagram below). There is progress on all indicators, and except for the indicator on the share of girls who leave school due to child marriage, progress is stronger than anticipated.

An outcome indicator that was removed from the results framework before midline is the number of child marriage cases prosecuted through the justice system. No data are therefore reported, but informants in CSOs indicate that around 1,000 cases of child marriage are reported in the country annually, most of them from Maputo city. However, only an estimated 3–5% end up in a prosecution.

It is useful to dive a bit into what we can learn from each of these indicators.

Community members who believe that child marriage is an unacceptable practice. This indicator is constructed based on responses to eight statements, six of which are about the potential benefits of child marriage (such as whether child marriage can improve financial conditions, security for the girl, health of the baby, reputation of the family, etc.). In addition, there are statements about whether a girl is ready to marry when she starts menstruating and whether she should respect the family’s decision to marry even if she disagrees herself. Respondents who on average disagree or strongly disagree with the eight statements are categorized as finding child marriage unacceptable.

The name of this indicator does not reflect precisely what is measured. A more accurate name would be the share who disagrees with beliefs that may promote child marriage. This is not the same as finding child marriage unacceptable.

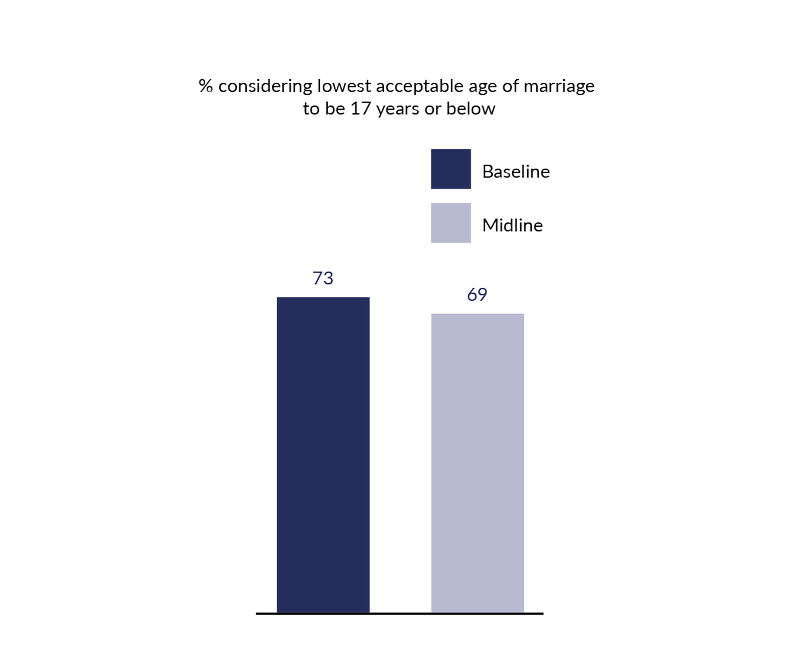

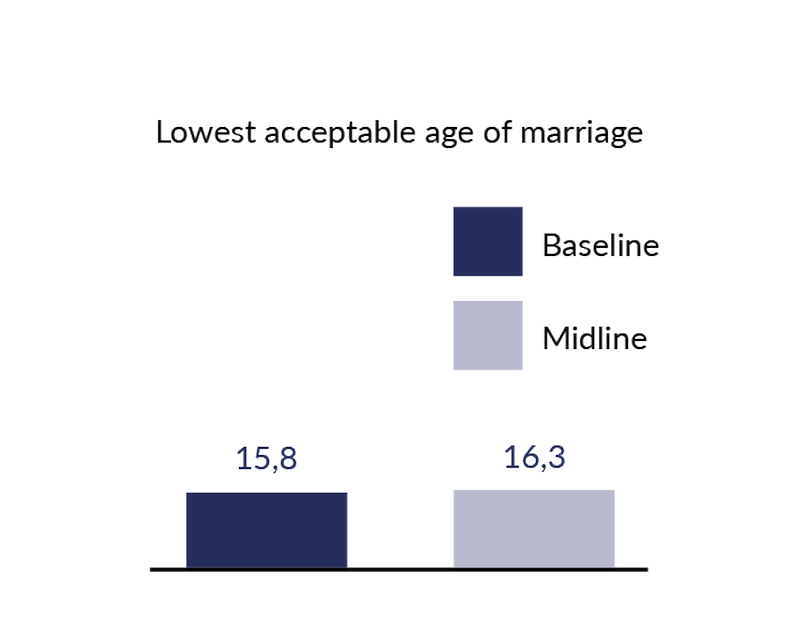

A more accurate picture of attitudes toward child marriage can be obtained from responses to a question about what is seen as the lowest acceptable age of marriage. At baseline, 73% answered that the lowest acceptable age is 17 years or less, with an average of 15.8 years. Child marriage was thus clearly seen as acceptable by a large majority.

The lowest acceptable age of marriage increased from 15.8 at baseline to 16.3 years at midline, and the share who clearly regarded child marriage as acceptable dropped from 73% to 69%. This may be a result of the project, but it can also be a result of more people answering what is expected now that child marriage has been criminalized. (When asked about the legal age of marriage, 95% responded 18 years or above.)

One caveat is needed here: It is unclear how comparable baseline and midline samples are, because the communities included in the sample at baseline and midline are not identical. The number of communities was reduced from 54 in baseline to 28 in midline due to Covid-related challenges, and it is unclear how well the procedure for selecting these 28 communities ensures comparability.

Communities that have taken steps towards a community free of child marriage. This indicator is a combined measure of three related issues:

- Whether the CCPC contributed to at least one campaign against child marriage during the past year.

- Whether the community made commitments of other kinds to fight child marriage (anything from voluntary work to raise awareness to declarations against child marriage).

- Whether anyone in the community was prosecuted for child marriage during the past year.

The indicator measures the share of communities that have met all these criteria. A more precise name of the indicator would therefore be percent of communities that have taken at least three different steps towards a community free of child marriage in the past year. The data is collected through focus group discussions in the same 28 communities that participate in the household survey.

The most common activity is for CCPCs to contribute to campaigns against child marriage. This has happened in 68% of the communities. Other efforts were mainly voluntary awareness raising of various kinds.

Eight of the 28 communities (29%) fulfilled all three criteria. Given the small sample, there is considerable uncertainty attached to this estimate. With 95% confidence we can assume that the true value is in the range 11–46%. It would be valuable for the interpretations, both here and elsewhere, to display such uncertainties. In this case, for example, we cannot conclude from the data whether the achievement is above or below the midline target of 25%.

Share of girls who return to school after child marriage or teenage pregnancy and share of girls who drop out due to child marriage / early pregnancy. The share of girls who return to school shows impressive progress, suggesting that almost all girls now get back to school. Unfortunately, this conclusion is most likely not true.

What the underlying data do show is that there has been a huge overall reduction in school dropouts in the schools where SC and partners operate, including in the number of dropouts due to child marriage.

The extent to which child marriage is a reason for dropping out is unclear. The figures may be taken to suggest that other reasons are much more important. However, data on reasons for dropping out is incomplete. The schools, which report on dropouts, often have incomplete information on its causes. Therefore, child marriage may be a more important reason for dropping out than shown in the midterm report. During the programme period, CCPCs have worked with school managements to report the causes of dropouts more completely. If successful, this will increase the reported share of dropouts caused by child marriage, even if everything else is constant (fewer missing observations will lead to a higher share for all causes of dropout).

Assuming, reasonably, that reporting on causes has not become less complete over time, we can conclude that there has been a large reduction in the number of dropouts due to child marriage. This is currently not reflected in the reported outcomes. It would be more informative to replace the current indicator (share of dropouts due to child marriage) with the absolute number of dropouts due to child marriage.

As mentioned, the share of girls who return to school after child marriage is probably much lower than reported. The reason is that this indicator is based on figures for dropouts and returns in the same year. In the year used to calculated midline indicators, 26 girls dropped out and 25 returned, resulting in a calculated return rate of 96%. However, those who returned this year are to some extent those girls who dropped out in earlier years when the number of dropouts due to child marriage was much higher. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the true figure is much lower that the reported one.

Share of children with adequate knowledge of adolescent sexual and reproductive health. This indicator shows a steady increase, from 48% to 60%. The indicator measures the share of correct answers to a battery of questions about family planning and HIV. The respondents are both from primary school (5th grade) and secondary school (8th and 9th grade) and are randomly chosen among all students. Some of them, but far from all, have participated in sessions on sexual and reproductive health (SRH). It is unclear to what extent the indicator measures improvements in knowledge among those who have participated in SHR sessions vs. improvements in for those who have not. Being able to distinguish between those categories would have been helpful for assessing the effects of the sessions.

Unintended effects. Several communities have concluded that poverty is a main reason why girls get married and that this barrier needs to be addressed to bring girls back to school. With assistance from SC, these communities provided resources for income-generating activities to the family of the girl. This has been done in 17 communities, and 12 of them have now managed to sustain this arrangement without external support.

Explanations

Contributions by SC and partners

SC and partners have worked purposefully to increase awareness about the law against child marriage, to increase knowledge about the harmful effects of child marriage, and to stimulate reflection in communities about current practices. At midline, 4,619 participants had graduated from the community dialogue programme. This is significantly less than planned (8,625). SC and partners explained that Covid delayed the implementation. The activity also had other start-up challenges because it was initially implemented with random participants in each session. It was then changed into a structured programme with eight sessions for all participants.

SC and partners also made targeted efforts to strengthen the referral system for cases of child marriage and other cases of violence, both through the CCPCs and through strengthening the formal child protection mechanisms. There has been a strong focus on training of the CCPCs to identify and report on child protection cases, in addition to other issues such as education and inclusion of children with disabilities. Efforts have also been made to strengthen capacities of the formal system and the coordination between formal and informal mechanisms.

Strengthening of the CCPCs may have contributed to the reduction in school dropouts, to increasing the return rate, as well as to increased awareness about how to report cases. It may also have increased the number of reported cases. Last year, the province attorney received 97 reports on child marriage, of which 43 are from the districts where SC and partners operate. This is almost twice the expected share based on population size. Nevertheless, underreporting is still huge, according to government officials. In Tamara district, for instance, where attitudes towards child marriage are more favorable than in other districts, only one case was reported.

A number of other measures were also planned for to get girls back to school, including scholarships to vulnerable girls. We were not able to get a full picture of the scale and scope of these activities, but our impression is that less emphasis has been placed on these parts of the programme in Manica and that some activities have been scaled down compared to original plans. At the same time, some communities have pushed for increased attention on these issues (see above). In Maputo, SC supports several CSOs that work purposefully to rescue girls from child marriage and bring them back to school.

The number of children trained in sexual and reproductive health developed as planned during Covid, but progress slowed down in 2021 (to around 50% of the planned scale). The content has been adapted to the context by including many topics other than SRH. This has increased acceptability but has likely weakened the impact of SHR trainings. Progress on this indicator should be expected to take time as a relatively low percentage of the children are trained at any given point in time.

External contributing factors

Despite the passing of the law against child marriage, several external factors are believed to contribute to continued high marriage rates and low rates of reporting.

Economic factors: There are economic benefits of child marriage for poorer households. By marrying a girl to a wealthier man, the family will be entitled to a stream of benefits over time, and in some cases a bride price is received. They will also have one person less to feed. Economic factors also create a strong social pressure not to denounce cases and to withdraw reported cases from the justice system: How can we survive if your father is going to jail because he allowed you to marry, family members might say, according to our informants among SC partners.

Cultural norms: Child marriage is an area in which national law conflicts with customary norms. Although these norms are not accepted as formal law, they tend to have the upper hand unless there is strong enforcement of national law by the state. “We have always done it like this”, is a common sentiment. Marriage provides status, and it is believed that marrying off a virgin is preferrable, including for the possibility to obtain a higher bride price. In contexts where girls engage in sexual activity early, parents have an incentive to marry them off sooner. The practice of polygamy reinforces the practice of child marriage, as it enhances opportunities to marry off a larger number of girls to wealthier men. It also gives status and privileges to marry a girl to community leaders, who often have several wives.

Dysfunctional justice system: These cultural beliefs are shared also by the police, and it is therefore common not to follow up on reported cases. Other police officers see opportunities for exploitation and increased incomes. Community members stated that there are rumors that reports about child marriage are just a way to make the police rich (by utilizing the situation to obtain bribes from the perpetrator).

Long distances between where people live and where the police and courts are located contribute to poor follow up of reported cases. The feedback mechanisms from the justice system back to the communities are also not working well. When communities do not know what happened to reported cases, they lose motivation to report. Likewise, when perpetrators return to communities without being punished, there may be confusion about whether the court has done its job or not.

Adding to these factors, the criminalization contributes to increased secrecy around child marriage and thus reduced likelihood of reporting. Child marriage is linked with other child protection risks including unsafe migration or movement of children and family separation, which creates opportunities for “hiding” child marriage cases. One example mentioned is that girls may be sent to town, pretending it is for going to school, while in reality it is a child marriage.

Theory of change

SCN presents the high-level theory of change in the Norad application. It says that children are protected if there is

- quality education for children affected by child marriage / teenage pregnancy, and

- transformed norms that reduce violence against children, and

- strengthened child protection systems that prevent, identify, and respond to violence against children.

However, we have not seen a more detailed theory of change explaining how activities and outcomes are linked at the country level, including underlying assumptions. We believe that developing such theories of change would be helpful for future project planning and evaluations.

Using the results framework presented above as a substitute, we sometimes struggle to see how the pieces are logically connected. For instance, the results framework seems to assume that strengthening referral mechanisms for child marriage will lead to norm change. While such an effect cannot be ruled out, we find it more reasonable to treat the strengthening of the referral system as a separate outcome (as is the case in the high-level theory of change).

We thus assume that the key propositions of the theory of change behind the goal of reducing child marriage in Mozambique are:

- Norms related to child marriage will change through awareness raising and community dialogues.

- Reporting mechanisms will be strengthened through training and follow up of CCPCs.

- Together, these factors will contribute to a reduction in child marriage.

The credibility of this theory was strengthened with the passing of the law against child marriage. Not only did it create a new platform for dissemination activities and community dialogues, it also strengthened the case for reporting, and it had a potential norm-changing function in itself.

Nevertheless, several of our informants among SC partners express doubts about the validity of the theory of change. “It is not enough to change the mindset of people”, one of the partners observed. Our impression, based on the conversation we had, is that the combined effects of the economic and cultural factors that continue to promote child marriage, as well as the governance issues that prevent reporting and prosecution, are too strong for the programme to induce behavioral change at scale.

Several of SC’s partners have started taking the consequence of this already, albeit at a small scale. Examples include various kinds of economic support and life skill trainings to vulnerable girls. There are several ways of doing this, and there are many pitfalls. A clearer strategy seems to be needed to confront the economic drivers that push vulnerable girls into child marriage and prevent them from going back even if they are encouraged to do so. Those measures that were included in the SC programme from the outset to address these issues do not seem to have worked well enough.

It is perhaps even more difficult to address the governance issues. One of the partners has started working systematically on improving the feedback mechanisms from the justice system to communities about how cases are treated. Further experimentation and analysis may reveal whether this one or alternative strategies can make a difference to reporting behavior.

Another clear message from a couple of SC’s partners is that mass media campaigns will have limited impact in a situation where customary norms are so strong. It will be more effective to work through community authorities.

Next, consider the theory of change for how to increase access to education for children at risk of or affected by child marriage or teenage pregnancy. The results framework suggests that access to education will be improved through:

- Measures to get girls back to school after child marriage, such as stronger identification and follow-up mechanisms from the CCPCs and from schools.

- Enhanced support for the child of the young mothers.

- Improved access to education in sexual and reproductive health.

It is quite clear how SC and partners work to increase access to education for children affected by child marriage and teenage pregnancy. But as discussed above, several informants question whether these measures are effective enough to bring them back to school.

It is less clear what is meant by the ambition to improve education for those at risk. The largest group at risk of child marriage is probably those who do not continue from primary to secondary school. Programme activities do not appear to target this group specifically.

It is also not clear what role adolescent sexual and reproductive health knowledge and services play in the theory of change. As a mechanism to strengthen knowledge about sexual and reproductive health, its potential impact is questionable, as little time appears to be spent on the SRH part. Nor is it likely to be an impactful mechanism for preventing teenage pregnancies and child marriages resulting from premarital sex, both because of the low intensity of the SRH intervention and because informants among SC partners suggest it is less common in Manica to marry as a result of first becoming pregnant. Finally, it is unlikely to be a robust mechanism for increasing access to quality education as it relies on child peer educators with limited training and experience in pedagogy.

Marginalized groups

SC has a strong focus on gender equality in all its programme components. The marginalized children in the context of child marriage are first and foremost those girls who are most at risk of being married away.

The programme has a strong focus on identifying girls at risk so long as they are in school, and to bring them back to school as soon as possible. The CPCCs play a key role in identifying and supporting these girls.

We did not observe the same level of attention to girls who are out of school permanently because they did not progress to secondary school. This is definitively a high-risk group.

SC and partners also seem to have succeeded in increasing focus on the interests and rights of disabled children. This issue was frequently mentioned as an important concern by partners and community members, including children.

When it comes to child marriage, this is an issue that is less relevant for disabled children. Our informants were not aware of any instances of child marriage with disabled children.

Much of the work targeting children with disabilities focuses on access to education. For instance, the CCPCs have the inclusion of children with disabilities in school as one of their focus areas. The CCPCs work with School Councils to ensure that education is offered to children with disabilities, and they sensitize communities so that children with disabilities get into school. Likewise, the group sessions on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and other issues have the interests of disabled children as one of their topics.

Since the issue of education is not covered by this review, we have not systematically gathered information about it. Our informants among government officials and SC partners nevertheless indicated that there is a long way to go before the right to education is fulfilled for children with disabilities. Stigmas prevent parents from taking their children to school, and the schools often lack required infrastructure. Existing plans for including children with disabilities are generic and do not address the specific issues that matter for each child. Teachers also lack skills to accommodate their learning needs. Many children with less severe disabilities are likely to go unnoticed. It is illustrative that the teachers at a school with 3,000 children claimed that they do not have any children with a disability in their community.

Child protection South Sudan

The programme’s objective in South Sudan is to ensure that boys and girls (ages 6-17) can live free from violence both at home and at school. Issue two pays particular attention to the home dimension. To achieve this goal three intermediary outcomes are proposed: to make sure that boys and girls feel valued, respected, and safe within their families and community (outcome 1); to make sure that interactions between parents and children are positive, non-discriminatory, and violence-free (outcome 2); and to ensure that social and gender norms accept positive parenting and partnering without violence (outcome 3).

The assessment of outcome 1 involves the use of a survey of boys and girls to assess their confidence and well-being when interacting with adults in their lives. It also includes responding to reported child protection cases and identifying vulnerable children using the “vulnerability matrix”. The matrix helps determine the assistance children receive based on their need level. Assistance offered ranges from food items to referrals to psycho-social support. The success of the group sessions and surveys hinges on community mentors being trained in safeguarding policy and practice and providing them with incentives (refreshments, materials etc.).

To achieve outcome 2, positive non-discriminatory and violence-free parent-child relationships, the program conducts training sessions with parents, caregivers, and sometimes with children. These sessions include a pre-post survey that captures changes in attitudes. The survey is conducted at the beginning of the training and after the trainings have ended. Save the Children staff, partners, and community mentors are trained on positive parenting and safeguarding policies and practices. For those households with children under 5 years, monthly home visits are also conducted.

Outcome 3’s programmatic components include community dialogues and celebrations that engage relevant stakeholders, state leaders and other community leaders on parenting without violence. This aspect of the program also provides communities with child protection reporting systems that help them identify, report, and refer cases of violence. These reporting systems are led by child protection community-based networks that receive training and materials that facilitate their work.

Reported results

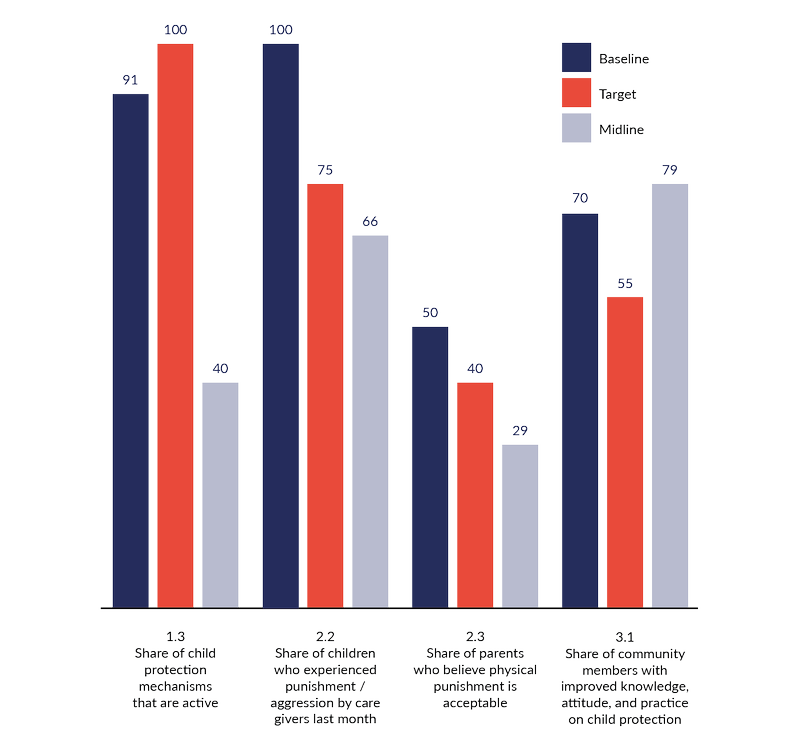

Four outcome indicators on child protection have data both at baseline and midline. Positive change is reported on three of the indicators.

Share of child protection mechanisms that are active shows that relative to 100% target, only 40% were active at the midline. There is no reliable baseline data available for this indicator. Active protection mechanisms are defined as those that have regular meetings, are able to implement decisions reached during meetings, conduct community mobilization activities, have good working relationships with case workers and service providers, and can identify and refer children with protection concerns to case workers. Case workers then provide at-risk children with appropriate care and where they are unable to do so, refer the cases to other agencies and government bodies.

When it comes to activities and outputs, the program has, since 2020, trained 255 community mentors who are responsible for safeguarding policies, practices, and conducting group sessions with boys and girls. This number is slightly less (33) than the target. 161 of those trained are male and 94 are women. Community mentors tend to also be teachers in the local community. Therefore, if there are more male than female teachers, this could explain the heavy male presence among community mentors.

The share of children who experienced physical punishment or psychological aggression by parents or care givers last month decreased substantially from 100% to 66%, well below target of 75%.

The share of parents who believe physical punishment is acceptable decreased from 50% at baseline to 29% at midline, also well below the target of 40%. The weekly trainings were effective in helping parents update their attitudes regarding the impact of violence on their parenting.

The share of community members with improved knowledge, attitude, and practice on child protection increased from 70% to 79%. For unknown reasons, the target here was set below the baseline value.

Three outcome indicators are reported with midline values only:

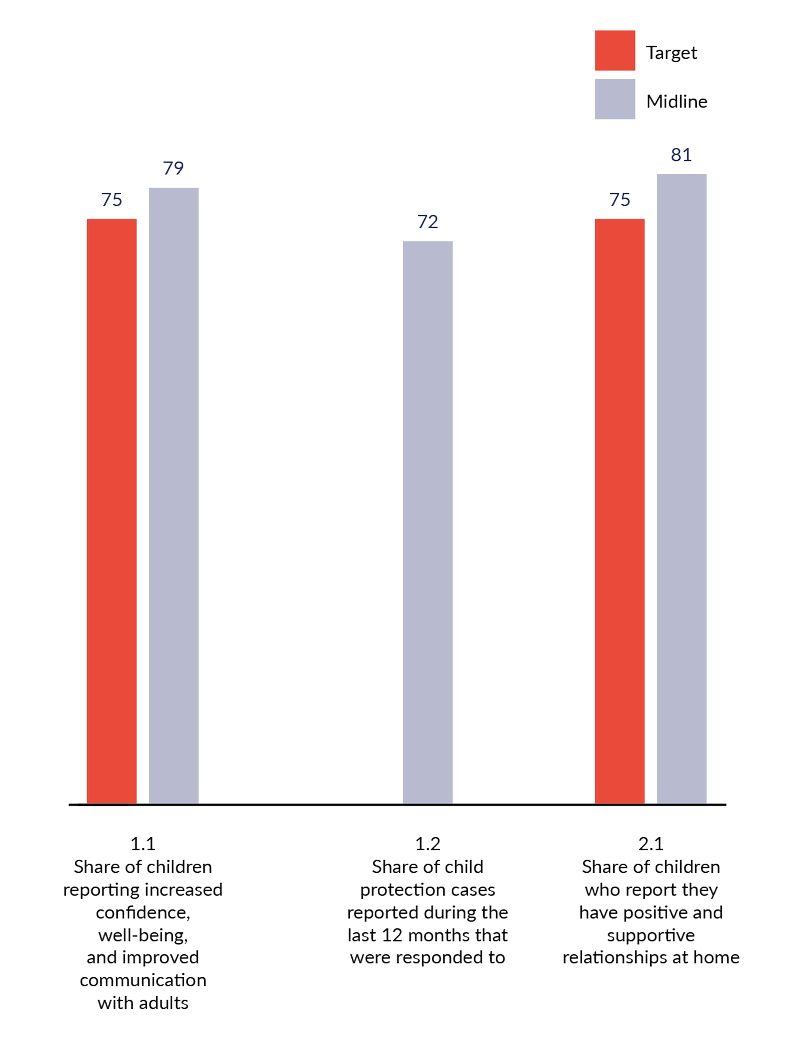

Children’s confidence in their interactions with adult family members is measured by asking them at the end of trainings how their relations with adults have changed. 79% reported an improvement. Without a measure of the change in confidence levels, it is difficult to assess the significance of these results.

98 child protection cases had been reported to the child protection mechanisms by parents, children and community members during the past 12 months. 72% of them had been responded to. Response to these cases refers to activities ranging from offering food stuffs, psychosocial support, and referrals to other agencies, including the police.

A large share of children (81%) report that they have positive and supportive relationships at home. We are uncertain about the validity of these data, as another set of values are also reported in the results framework (see line 32), which seem to suggest that the share is lower (66%). Moreover, the data from 2020 seems to suggest that both a pre-test and a post-test is conducted, and that the values in the post-test are lower. We don’t know whether 2021 figures refer to pre- or post-test.

The number of boys and girls who accessed safe, responsive, and accountable reporting mechanisms across the 30 school communities has been close to the target of 750 per year, with the exception of 2021 when only 247 were reached (see figure below). The data in 2021 and 2022 do not disaggregated by state, making it difficult to determine whether the dip is driven by a particular state. It is likely, however, that a combination of the pandemic and severe flooding in Bor affected the activity and accessibility of reporting mechanisms. Interviews with program implementers in Rumbek, however, stated that they have been able to consistently keep these mechanisms accessible and operational. It is worth noting that in Bor and Rumbek, 100% of the child protection cases involving children with disabilities were responded to. The data, however, does not disaggregate those with high protection by disability status.

The number of community dialogues held to change norms regarding positive parenting (parenting without violence) were 42 up to midline, which is almost 200 fewer than planned. However, this activity was up to speed in 2022 with 160 dialogues conducted. The data does not tell us how many individuals attended and how these dialogues changed norms.

The program established 16 community-based mechanisms that refer, report, and provide services addressing violence against children in the home. Through 2022, the program had trained 286 professionals to promote zero tolerance of violence and discrimination at home, which is well below the 480 target.

Explanations

SC and implementing partners

SC and partners have worked to reduce boys’ and girls’ experiences of violence both at home and in the community. The Covid-19 pandemic affected the program’s ability to meet its desired targets in Bor. Severe flooding in the period 2020-2021 displaced many families in the area. This meant that as families sought refuge in other areas, they were no longer accessible to program staff. In Rumbek, implementing partners stated that they were able to maintain access to 742 boys and girls on an annual basis without much interruption despite the pandemic. We are, however, unable to see this in the framework results data because the relevant data after 2020 is not disaggregated by state, making it difficult to verify.

Interviews with implementing partners and SC staff also reveal that the program is threatened by high turnover rates of teachers who also serve as community mentors. This role is best suited to teachers in local communities because of their embedded nature and familiarity with the home situation of boys and girls. As teachers in community schools gain training in both their teaching and as community mentors, they acquire new skills that make them marketable in other sectors. Their incentive to stay in the public education sector are low. As these teachers leave for more lucrative opportunities, new individuals need to be recruited and trained. The data, however, does not currently reflect these dynamics.

For those community mentors (teachers) who remain in the program, there is little incentive to continue monitoring parent-child relationships in the community once the year-long training is complete. This, according to interviews, is because incentives to community mentors stop following the training’s completion. Their role as community mentor becomes uncompensated and voluntary.

Implementing partners expressed concern that the level of men’s participation in the trainings on parenting without violence would affect the quality of the outcome. Though men would participate in the first training session, this engagement would not be sustained over the 12 weeks. This then required implementing partner follow up and encouraging male participation, which nonetheless remained sporadic and inconsistent. The explanation offered for this gendered participation is the prevailing norm of women being responsible for children and their discipline. Fathers, interviews revealed, become actively involved in parenting only when a serious issue arises. Women are therefore seen as those with a vested interest in attending the trainings on parenting without violence. Men’s limited training participation risks reinforcing gender stereotypes and undermining program efficacy.

External contributing factors

Cultural norms: South Sudan is a patriarchal and hierarchical society. The belief is that children should do as their parents say because they know best. Children are not individuals but extensions of their parents and larger family. Their behavior, be it good or bad, is seen as a reflection of the family and their upbringing. To both signal proper parenting style and disabuse children of bad behavior, parents often rely on corporal punishment. Changing this norm in favor of parenting without violence will take time and investment in programs that target behavioral and not just attitudinal change.

Post conflict setting: South Sudan is still recovering from civil war and is grappling with a weak economic system. Parents and caregivers in these settings are often pre-occupied with poverty, socioeconomic insecurity, and morbidity. Their focus is on providing their children with food, water, shelter, and education, rather than on disciplinary strategies. When asked about the biggest impact the NORAD programs have had during focus group discussions, parents emphasized access to schooling, books, and uniforms rather than the parenting without violence aspects.

Theory of change

The theory of change outlined in the frame agreement is ambitious. It seeks to change norms regarding children’s status and parenting styles in a hierarchical post-conflict setting. By having community-based child protection mechanisms identify and respond to children experiencing violence while improving both parent-child relationships and norms regarding parenting without violence, it is believed that children will be empowered and live lives free from violence. The program’s focus on ending corporal punishment in the home extends the reach of the Child Act (2008), which prohibits the practice from institutions like schools, prison and reformatories (Section 21b), and that those who are convicted will be penalized through prison or fines (Section 35). South Sudan’s complex humanitarian situation and breakdown in governance has fostered a culture of impunity related to violence, rendering the law ineffective. The “children are protected” program goals and activities provide concrete ways to gradually change norms and protect children in ways that laws, by themselves, cannot.

The program seeks to change how children and their parents interact through trainings, dialogues, reporting systems and case management. The use of the vulnerability matrix to identify those at most risk for violence at home assumes and tries to address the link between poverty/scarcity and violence. The trainings geared towards parents and identification of violent symptoms fit the theory of change. However, several informants expressed reservations about this 12-week program. They doubted that attitudinal changes would necessarily lead to behavioral change.

It is also less clear how increasing children’s confidence leads to their protection. In settings where hierarchy matters, expression of confidence could leave children vulnerable to violence. Though children may learn to say no or to report violations, these actions may be perceived as challenging parental authority and betraying family ties. In settings where one is considered first as a group member rather than an individual, asserting independence may isolate them and lead to negative outcomes. The theory of change, therefore, needs a clearer articulation of the kind of confidence being fostered and practiced. For example, how these relationships can be negotiated to help both children and parents understand that the confidence built is meant to build independent and responsible individuals.

Marginalized groups

The program considers girls/women and persons with disabilities as marginalized communities that need to be incorporated into the programming. This is not only at the level of children but also parents, care givers, and community mentors. Gender equality among pupils has largely been a success with almost similar proportions from either sex participating. There is, however, a strong need for better disaggregated data by sex across program locations. Better data is also needed to assess whether the program has reached the desired number of children with disabilities. Though cases involving children with disabilities were handled, it is not clear how these compare to targets. This is because there are still strong ideas about the place of persons with disabilities in society. They are often not in public life making it difficult to identify them and encourage them to attend school, which is the main pipeline into the parenting without violence program.

Child rights Mozambique

Objectives and activities

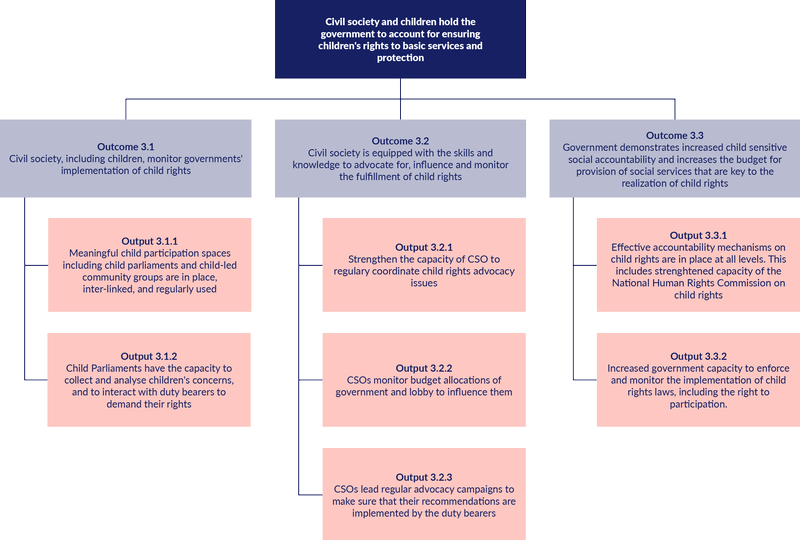

The objective is that civil society and children hold the government to account for ensuring children’s rights to basic services and protection. Intermediary outcomes are: 1) child rights issues are monitored by civil society, including by children themselves, 2) civil society has the knowledge and skills to monitor and advocate for child rights, and 3) the government demonstrates sensitivity to child rights, including by increasing the budget for services that are key to the realization of child rights.

Notice that child participation is not mentioned as an overarching goal.

Key activities to promote monitoring of child rights are child clubs at the school level and child parliaments at the district, province, and national levels. Child clubs gather children between 6 and 17 years of age, at least one child from each school class. The focus is on raising awareness about child rights. The clubs may also collect concerns about child rights violations, and occasionally these are passed on to the child parliament. Child parliaments gather children between 10 and 17 years of age and are elected by the child clubs. Their main tasks are to report on child rights issues to governments at all levels and to international child rights monitoring processes. Child parliaments meet for ordinary sessions once a year at district level and every second year at the province level. Both child clubs and child parliaments are part of national structures. SC’s role is to assist in making these structures function as intended.

The capacity of civil society to monitor and advocate for child rights is promoted through a variety of activities, from trainings of civil society organizations to speak out about child right violations to the establishment of platforms for increased collaboration on advocating for children’s rights. Another important activity is the establishment of Child-Centred Social Accountability Groups (CCSA) at the community level, which systematically assess education services in relation to government standards and use this as an advocacy tool to improve services.

To promote government sensitivity to child rights, focus has been on strengthening the role of the National Human Rights Commission through trainings and economic support for field visits. In addition, CSOs have been trained and encouraged to hold government institutions accountable by demanding that they report on child right issues. CSOs have also been supported to do monitoring of government budgets.

Reported results

Monitoring of child rights

Government officials report that an important result of the work by SC and partners is that children have become able to speak out about their rights. They had observed high awareness of child rights by children in child parliaments and increasing awareness in communities.

One of the partner organizations reported that child participation in decision making has improved, that people with influence have understood that they need to involve children.

At midline, 1,461 children were involved in child clubs or other child-led community groups. This is >50% above target. Around 2/3 of these children had been trained on child rights and advocacy. This is significantly less than planned.

The normal meeting frequency of child clubs is every second week, but meetings are sometimes cancelled due to lack of support from adults.

Our impression from encounters with child club members is that the methods used to raise awareness about child rights are effective. The children were able to clearly identify a number of core child rights. They also claimed that they had not heard about some of the rights anywhere else, for instance the right to express their opinion.

The idea is that child club members will disseminate knowledge back to their classmates. We were not able to assess the extent to which this actually happens.

Child club members also had high awareness of channels for voicing concerns about child rights violations, including the national child helpline, complaint boxes, police, school committees, etc. They seemed less aware of the child parliaments and their role.

The national child helpline is used extensively. They receive 10,000 calls each month, 350 of which are related to child abuse. Complaint boxes were used to a limited extent at schools we visited.

Child-Centred Social Accountability (CCSA) groups with child participation have been established in 47 communities, while the original plan was to do this in all 115 communities.

35 CCSAs have now completed their assessments of education services, and they report that 43% of deviations from government standards have been addressed to some extent. It would be interesting to know more about the significance of the changes, whether any major improvements in learning environment have taken place, and whether CCSAs have been able to influence governments to take action or have focused on issues that the community can address themselves.

Child parliaments at the district and province levels held their ordinary sessions (one per year) as planned in 2019 and 2021, but not in 2020. They voiced three concerns to duty bearers.

One child-led supplementary report has been submitted to the African Union as planned, though the timing was affected by delays in national reporting processes.

SC and partners actively adapted the programme during Covid. One result is the establishment of the Annual Child Report, which has been produced every year since 2020. This has created a platform for children to feed into the reports on child rights that are submitted to the United Nations and the African Union at regular intervals.

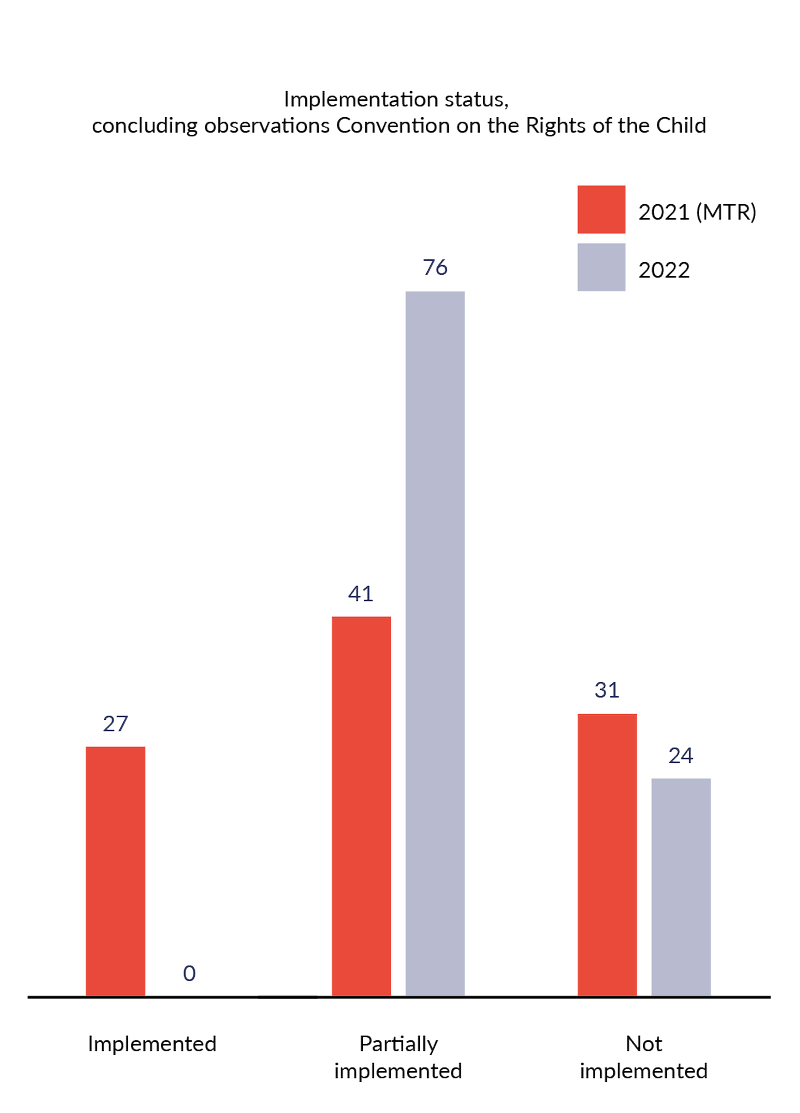

SC and partners monitor progress in the implementation of concluding observations from the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) Committee and the African Committee on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. Since this assessment was not done at baseline, it is difficult to assess progress. It is also worth asking whether the current monitoring approach is the most suitable. The figure below compares assessments made in 2021 (reported in the midterm review) and 2022. Many fewer recommendations are categorized as “implemented” in 2022. This is probably not due to deterioration of the child rights situation, but a result of a different (and likely more realistic) assessment. Reports on progress in this area would have been more accurate and more informative if they had included a description of the substantive changes that have (and have not) taken place, for example by mentioning the positive development with the new government action plan to deal with child labor.

Strengthen civil society organisations, including children, to promote child rights

An important achievement in this area has been the establishment of the 3R platform, a platform for collaboration between three CSOs working on child rights. SC has been instrumental in nudging for this collaboration. Such nudging is important because financial incentives push CSOs towards partnering with their international counterparts rather than with each other in contexts where CSOs are mainly funded through grants from international organizations.

A quantitative indicator used for this outcome is the share of organizations supported by SC that are equipped to monitor and advocate for child rights. Progress on this indicator is measured as the share of civil society organizations that have either sent a formal appeal or a position paper to the government, or have called a press conference to speak out about child rights. Progress is above target, with 29% of the organizations fulfilling this criterion at baseline compared to 67% at midline.

The fact that SC has been working with an increasing number of organizations over time makes it hard to interpret this indicator. There were four organizations at baseline, six at midline, and the plan is to extend to ten organizations at endline. It would be more informative if the indicator was presented as a fraction (e.g., 4 out of 6).

A second indicator is the share of civil society partners’ capacity enhancement milestones met. There are three milestones for each organization; one on governance structures, one on advocacy capacity, and one on fundraising. SC organizes trainings with around 30 staff from various organizations on these issues. Progress is according to plan, with 50% of milestones achieved at midline.

Strengthen government institutions to implement child rights

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has assigned a particular responsibility for child rights to one of its 11 commissioners, after being nudged by SC and others to do so.

Support from SC has enabled the NHRC to fulfill its mission. The NHRC has been able to do more frequent visits to provinces with a focus on child rights issues. During these visits, the NHRC meets stakeholders at the province level and perhaps one or two districts, meets the child parliaments, and does some follow-up on reported cases. SC has supported such trips to 2 out of 11 provinces per year. Although the NHRC does more frequent visits with a broader human rights focus, the frequency is too low for the NHRC to do effective monitoring of developments over time. It is also not possible to do timely follow up on individual cases around the country. According to NHRC staff, this discourages people from using this mechanism to report human rights violations.

SC and partners also advocate for and support the publishing of reports by government institutions on issues related to child rights. Among the institutions that according to SC are expected to do such reporting, the share that does so has increased from 33% to 66% from baseline to midline, which is above target.

One of the outcomes that is supposed to be reported is the number of policies or laws changed with the support of SC, but this was not done in the midterm report. Country office staff expressed slight reluctance for claiming this kind of impact, because long term ability to have impact depends on SC being humble about its own role. In any case, we are talking about a low number of policies/laws, and a qualitative description of changes and assessment of SC’s role in the processes would both be more informative and a better tool for learning.

A positive development that should be mentioned, in addition to the law against child marriage, is a new land policy that includes six points regarding child rights. An initiative that has not been implemented as planned is the attempt to induce the government to develop and adopt a child participation strategy. The budget for this activity was diverted to Covid-related activities.

We do not have information about the development in government budgets to address child rights issues. According to SC, the work on budget advocacy has not progressed as far as expected, due to limited budget advocacy capacity in place in the CSOs. SC is supporting capacity building in this area, and SC partners recently established a working group on public budget advocacy and produced relevant advocacy material.

Explanations

Contributions by SC and partners

Through their support for child clubs, SC and partners are likely making a significant difference to awareness about child rights among the members of the child clubs. According to our informants among SC partners, child clubs do not function well unless there is support from organisations like SC and partners, even though this is supposed to be a national structure.

The same seems to be the case for child parliaments. Members of child parliaments in Manica claim that children in other areas become demotivated to participate because they lack support.

Some partners that were part of the programme from the beginning had insufficient capacity to implement child rights work in Manica province. A new partner was brought on board from 2020. This work has progressed well since then, but the delay contributed to fewer children being trained in child rights and advocacy than planned. It also contributed to a significant reduction in the number of communities with Child-Centred Social Accountability groups compared to the initial plan.

It is still a challenge that there is an insufficient number of adults from SC’s partner organizations to support the child clubs. As a result, child club meetings are sometimes canceled. A potential solution mentioned by an SC partner is to train more people in the communities to support the child clubs.

It has also been a challenge to make sure all the different community groups are functioning as intended. This has been addressed by creating community platforms for civil society in the communities. The platforms consist of six members (both adults and children) representing various community groups, and they get together to monitor each other’s performance.

In much of the other child rights work, e.g., with child parliaments and with other CSOs, SC is consciously taking a back seat. SC typically provides some light support such as financial assistance for travel and meetings, or nudges for more extensive collaboration across CSOs. SC also conducts trainings, both on technical and tactical issues. Tactics is important in this context as it is often difficult for CSOs to speak out on sensitive matters. SC plays an active role in sharing experiences and best practices on how to maneuver.

External contributing factors

Covid contributed to delayed progress in the child rights work throughout 2020 and in parts of 2021, especially at the community level. At the same time, SC quickly adapted its programme on child rights to the situation and initiated activities to monitor and speak out about child rights issues during the pandemic.

There are several other international NGOs working alongside SC towards similar objectives. These organizations appear to have been able to coordinate among themselves to support national CSOs and their collaboration platforms.

Theory of change

The high-level theory of change states that child rights will be implemented if there is

- advocacy (child rights are promoted by civil society and by the children themselves), and

- monitoring (civil society, including children, monitor the implementation of child rights), and

- government capacity (government institutions are strengthened to implement child rights).

Again, it would have been useful if a country-level theory of change had been developed with clearly expressed assumptions for each of the causal links from activities to outcomes and impacts. In its absence, we utilize the information provided by the results framework presented above, as far as it gets.

While our informants in SC and partner organizations appear to have a clear idea about the programme’s theory of change, the way it is expressed by the results framework is a bit confusing. For instance,

- While the top-level impact is that the government is held to account by civil society and children, outcome 3.3 is that the government demonstrates increased social accountability. The reverse order would be more logical.

- While outcome 3.2 focuses on civil society having skills and knowledge to monitor and advocate, several of the supporting outputs measure whether CSOs actually monitored and did advocacy. Again, the reverse order would be more logical.

- While outcome 3.1 is that civil society, including children, monitor child rights implementation, both outputs that support this outcome focus exclusively on children.

These observations suggest that theories of change are not utilized as they potentially could have been to assess the coherence of SC’s approach and to evaluate whether there is reason to add/drop/change any of the activities.

This said, we do believe it is quite possible to develop a coherent theory of change that most (if not all) activities that SC supports would fit nicely into.

Next, we comment on what might be some of the weaker links in such a hypothetical theory of change, based on inputs from our informants.

The effects of child participation. Even though child participation is not specified as an overarching goal of the programme, child participation in monitoring, reporting and advocacy is nevertheless an essential part of SC’s approach. This is indeed a key part of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. For instance, child clubs are supposed to feed into child parliaments, which are supposed to have dialogues with government bodies and report to the treaty-monitoring bodies of the UN and the AU.

Our impression based on meetings with children as well as government officials at the province level is that child participation is an effective strategy for building awareness about child rights and children’s confidence to speak out. This may have effects both in the short run and the long run, when this generation has reached adulthood and continues to make its voices heard.

However, the effect of child participation on implementation of child rights in the short run does not seem clear and obvious. First, there does not seem to be a strong link between child parliaments and child club members that are not members of the parliament. Most child club members did not appear to think of child parliaments as an important reporting channel. Secondly, low frequency of meetings in the child parliaments (ordinary sessions once a year or every second year) hardly makes for effective advocacy. Thirdly, as one informant noted, “it is not easy to get adults to focus on things like child rights. This is the hard part!”. And finally, the child-led supplementary reporting to international bodies may not substantively add much beyond what professional CSOs working on child rights may have reported already (we have not been able to assess this though).

Given that child participation serves multiple purposes, it might be worth thinking more carefully about how to get the most out of each. Much attention now appears to be devoted to reporting upwards in the system, to achieve impacts in the short run, while there is less attention to the long-term “citizen building” aspect of child participation. Many resourceful children participate in child parliaments. Perhaps these children could take a larger role in reporting back to the children they represent on how they work and what they do, to inspire even more children to engage?

Limited effect of advocacy. Successful advocacy usually requires persistent efforts over time. As pointed out above, several of the civil society partners have only recently, or have not yet, started speaking out on child rights issues. The current scale therefore seems to be too limited to expect all partners to do effective advocacy in the short run. Aspirations need to reflect this reality.

Marginalized groups

Recruitment and participation of marginalized groups. There is a strong focus on participation of marginalized groups in child rights activities. Boys and girls are equally represented in most activities where data are available, such as child clubs and various training activities for children.

According to the children we interviewed, disabled children are also represented in child clubs and child parliaments. However, we lack quantitative data to measure the extent, except that five disabled children were reported to be part of the child parliament in Manica district.

This suggests that the mechanism for selecting participants to child clubs and child parliaments do ensure representation of disabled children. This is far from obvious. Children are supposed to be elected to these tasks by their classmates, a procedure that normally will not favor marginalized children. But teachers have been told to encourage selection of disabled children, and this seems to have worked.

However, these mechanisms only work for disabled children that are in school. There is reason to believe that a large share of severely disabled children are still out of school, but data are lacking.

We also do not know whether disabled children were represented in the Community Child Social Accountability groups. These groups consist of both adults and children, and since these groups focus on access to education, it is important to have the perspectives of disabled children represented.

Taking into account the interests of marginalized children. Our impression is that the interests of disabled children is receiving increasing attention in SC’s work on child rights. Examples include:

- Children that had participated in the child clubs were quite aware about the importance of including disabled children.

- Community representatives mentioned the right of disabled children to education as one of their focus areas and claimed that they previously did not know that the disabled have the right to education.

- Child parliaments had the rights of the disabled on their agenda. They had for instance encouraged schools to build infrastructure to improve access for children using wheelchairs.

- The rights of disabled children were among the topics that were discussed in the peer educator groups at secondary schools.

- The national child helpline had received support to develop approaches that are more inclusive for the disabled.

These are all examples of mainstreaming of the interests of disabled children into programme activities. An important question is whether fulfilling the rights of this group requires more targeted activities. SCN’s application to Norad gives the impression that the ambition is to move in that direction, but we did not notice any such developments in Mozambique in the areas covered by this review.

Lack of data is currently preventing deeper analysis of the extent to which SC and partners are reaching disabled children. SCN has asked for collection of more data disaggregated by disability, and trainings took place in Mozambique to collect such data at midline. However, due to challenges with translating the tools to local languages, they were note able to collect reliable data.

Going forward, it seems important to carefully assess what data will be most needed to assess progress in reaching disabled children. A fundamental part will be to reliably measure the prevalence of disability at community level. Otherwise, it will be impossible to measure the degree of inclusion of disabled children in schools and elsewhere.

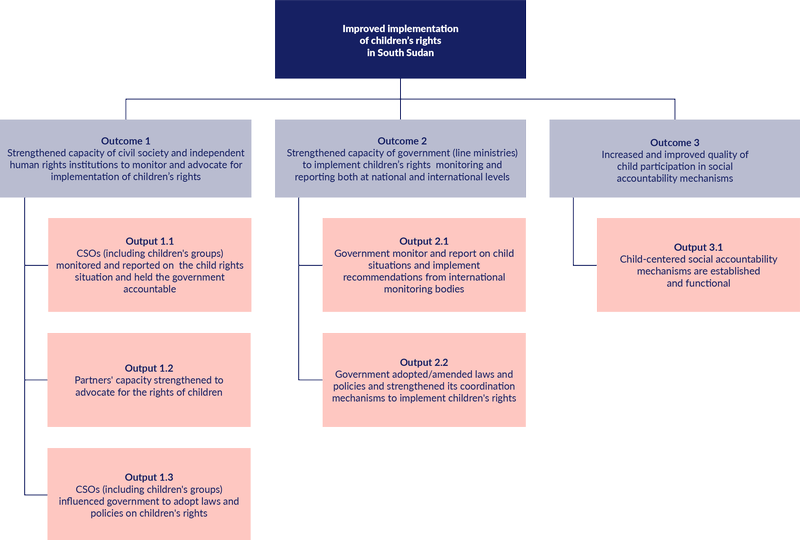

Child Rights South Sudan