An increasing number of Muslim women in politics: A step towards complementarity, not equality

Women in politics in the Middle East and Northern Africa

Sudanese Islamism: From exclusion to inclusion of women in politics

Sudan introduces a gender quota: A modern face of Islam?

How to cite this publication:

Liv Tønnessen (2018). An increasing number of Muslim women in politics: A step towards complementarity, not equality. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2018:3)

The number of Muslim women participating in political decision-making in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) is on the rise. This brief explores how Islamists in Sudan have interpreted complementarity over time and shows the flexibility of Islamic interpretation for and against women in politics highlighting the importance of the political context.

While complementarity historically domesticated women to rearing and caring for children, it is now employed to rally women into politics based on the claim that there is a need for both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ elements in politics to make sound decisions. This re-interpretation of complementarity has more to do with politics and specifically the responsibility put on Sudanese women’s shoulders to represent a ‘modern face of Islam’, not religious doctrine per se. And although the increase of women in politics in Sudan is most welcome, complementarity in praxis might not be particularly radical as it relegates women’s political decision making to ‘soft’ areas such as women’s issues, welfare and children’s wellbeing only.

While the MENA states have been notorious for having the lowest rates of women’s political representation in the world, changes are brewing, even in states dominated by Sharia rule and Islamism, such as Saudi Arabia and Sudan. While Islam has often been identified as the main culprit behind Muslim women’s exclusion from politics, Islamists are advocating for women’s increased presence in decision-making. However, they argue for it based on the principle of complementarity, not equality.

Women in politics in the Middle East and Northern Africa

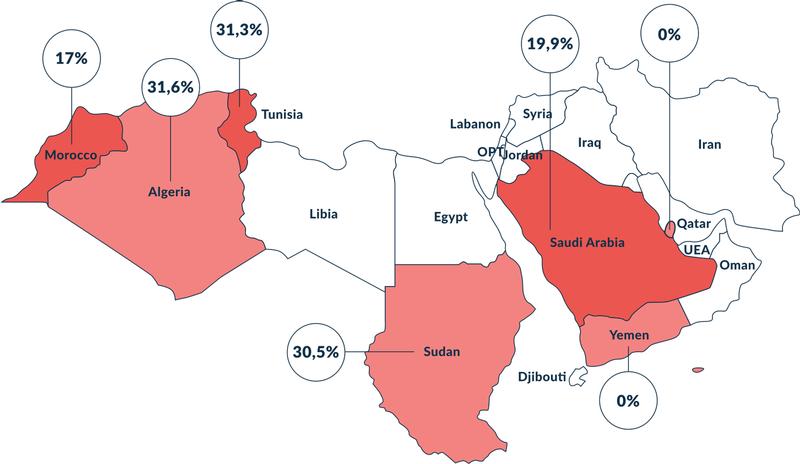

Women in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) continue to face numerous obstacles toward achieving parity in elected legislative bodies. MENA states have one of the lowest rates of women’s political representation at 18% compared to the global average at 22%. While the region continues to lag behind with some of the lowest percentages of women in national legislatures globally with Qatar and Yemen at staggering 0%, changes are brewing. Algeria (31.6%), Morocco (17%), Saudi Arabia (19.9%), and Tunisia (31.3%) are leading the new wave.

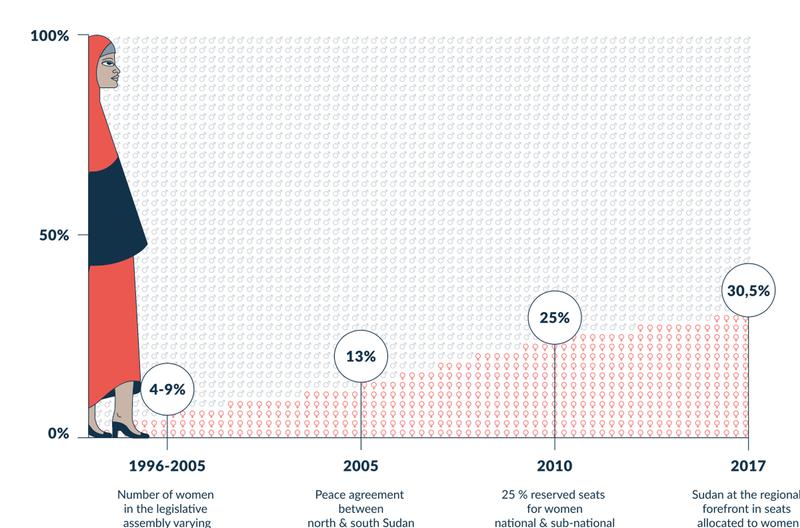

Sudan is at the forefront in terms of number of seats allocated to women in national and state legislative assemblies with 30.5%. Sudan has since a coup d’etat in 1989 been dominated by Islamism under the leadership of Omar al-Bashir. The political representation of Sudanese women has historically been chronically low both in elected (1956-1958,1964-1969,1985-1989) and appointed (1958-1964, 1969-1985, 1989-2010) National Assemblies. The Islamists followed in line with this historical trend with the number of women in the legislative assembly varying between 4% and 9% in the period between the first parliamentary elections in 1996 until the signing of the peace agreement between north and south Sudan in 2005. Then it increased in 2005 as part of the peace agreement to 13%. In 2010, onwards there was a significant increase in this number largely due to the introduction 25% reserved seats for women in national and sub-national legislative assemblies. Islamists first argued for women’s formal and equal right to political representation, and then later argued for affirmative action and introduction of a gender quota. However, their position on women’s political rights have dramatically changed from exclusion to inclusion; both positions mediated through the principle of complementarity.

"This hadith is the sledgehammer argument used by those who want to exclude women from politics.” (...) “this hadith is so important that it is practically impossible to discuss the question of women’s political rights without referring to it, debating it, and taking a position on it."

Sudanese Islamism: From exclusion to inclusion of women in politics

When the Sudan Women’s Union, established in 1952, put women’s right to vote and stand for election on the agenda, prominent female members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the forerunner to today’s Islamist party and regime, left the Union because they were principally against granting women political rights. At the time, the Muslim Brotherhood was postulating a view that domesticated women: they were encouraged to get an education, but not to work outside of the home and certainly not to participate in politics. Women in politics contradicted Islam, they said. And they based this view on a hadith that appears in Sahih al-Bukhari, one of six major hadith collections in Sunni Islam: “those who entrust their affairs to a woman will never know prosperity.” According to Fatima Mernissi,

This hadith is the sledgehammer argument used by those who want to exclude women from politics.” She adds that “this hadith is so important that it is practically impossible to discuss the question of women’s political rights without referring to it, debating it, and taking a position on it. 1

In their opinion, women and men are not equal, but complementary and should therefore have different rights and obligations, according to Islamic doctrine. The complementarity of roles is grounded in a view that men and women are biologically different and that women are of a more emotional nature than men, something that is suitable for rearing children, but not for making political decisions. Complementarity was interpreted to mean that politics was the realm of men only.

When the Muslim Brotherhood developed into a political party in 1964, this view slowly started to change. At the time, the Sudanese Communist Party was the only political party that included women’s political empowerment in its program. The other traditional Sudanese political parties, were traditional to its core, including their view on women in politics. But the Islamists created an Islamic alternative to women, interpreted by many as a pragmatic move to compete with the communist party for the female vote. The emerging Islamist ideologue, Hasan al-Turabi, spearheaded a new discourse on women and political participation within the frame of Islam, which has affected debates on women in politics until today.

According to Turabi (interview, 2009), “a woman can be a leader, a head of state, a minister. She can be everything a man can be”. However, this position remained controversial during the 1965 elections when Thuraiya Umbabi ran as the Islamist party’s first female candidate. Many members of the Muslim Brotherhood were hesitant to nominate a woman as a front candidate stating that women have no place in politics. Mohamed Sadiq al-Karuri is frequently mentioned as standing for this view. In connection with the 1965 elections, he infamously

“called for denying women their right of vote and candidacy on the grounds that women were like bottles, and a bottle would break if it underwent friction or collision, therefore women should stay at home and assume their duties of maternity, nursing and family care.”2

In 1973, Hasan al-Turabi published a pamphlet with the title Women between the Teachings of Religion and the Customs of Society, advocating strongly for women’s political rights. He noted that during the Prophetic era, for example, women were allowed to participate in congregational prayer, and they took an active role in military expeditions Muslim women participated actively in the community’s economic life, and acquire education. When the opinions of Muslims were sought to decide on a caliph after the assassination of Umar Ibn al-Khattab, women were included in the consultation process. Differing sharply with the traditional views held by Islamists and others at that time his pamphlet was written, Turabi came down decisively in favor of women’s presence in the public sphere:

(…)Women played a considerable role in public life during the life of the Prophet, and they contributed to the election of the third Caliph. Only afterwards were women denied their rightful place in public life, but this was history departing from the ideal.3

Turabi’s pamphlet invigorated Sudanese women’s advocacy for political inclusion. The changed view on women in politics that Turabi represented came out amid a heightened political and ideological confrontation between Islamists and communists on the campus of the University of Khartoum in the early 1970s. By partaking in electoral politics, Islamists’ saw the need to appeal to the female vote. Turabi and the Islamists created an Islamic alternative for women’s empowerment combining piety with political participation in an attempt to outmaneuver the ‘secular’ communists.

Since Mohamed Sadiq al-Karuri’s infamous statement in 1965, they have introduced a new understanding or interpretation of complementarity; an interpretation that allows for women’s inclusion into politics, first formally and equally to men and later through affirmative action. This move was supported by the construction of a modern Islam in which Sudanese Muslim women bear a heavy burden.

Sudan introduces a gender quota: A modern face of Islam?

Sudanese Islamists have proposed a route to women’s political empowerment that presents itself as an alternative to both traditional Islam and Western feminism. Muslim women became the face of a modern Islam as they combined piety with presence in the public sphere, including in politics. According to Ghazi Salah al-Din al-Atabani (interview, 2008), a previously high ranking representative in Bashir’s government;

“There is nothing in the Quran which supports an entirely patriarchal society; this is merely found in the Islamic jurisprudence and fatwas [legal opinions] from the ulema [religious clergy]. This is what we call the Bedouin or desert form of Islam, as in Saudi Arabia, where women cannot drive cars. The real revolution [of the Islamists] was the way we dealt with the women’s issue”.

It was clear that the Islamists wanted to show a modern face of Islam to the world both as an alternative to Western feminism, but also to what Ghazi Salah al-Din al-Atabani refer to as Bedoiun or desert form of Islam, meaning a traditional and in the opinion of many Islamists, backwards interpretation of Islamic scripture.

But what is particular about the Sudanese Islamists’ interpretation of Islam and what is so ‘modern’ about it? In the views of Islamist women, women’s extensive participation and presence in public life, after their role as mothers and caretakers are fulfilled, is evidence of a modern face of Islam which stands in stark contrast to the image of Muslim women presented in Western media as passive and powerless. They would often refer to Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan under Taliban as an example of ‘Bedouin Islam’ where the basic rights of Muslim women to public participation have been wrongfully forsaken.

The fact that women do not have equal representation in political decision-making stands in contrast to Islam. It is history deviating from the authentic.

While they argue for male guardianship within the private sphere of the family, men no longer should have guardianship over women within the political sphere. They call this gender equity (insaf), not gender equality which is regarded as Western feminism.

In 2008, Islamists together with women inside and outside of the government successfully lobbied for a 25 % woman’s quota for the national and state legislative assemblies in the National Election Act. But during the campaign for the quota in the 2008 Election Act, the women’s movement emphasized equality and human rights arguments, while Islamists stressed complementarity. Interestingly, the Islamist women situated a gender quota within affirmative action and make a point out of the fact that reserved seats for women contradicts the principle of equality. According to Farida Ibrahim (Interview, 2008);

Equality is not positive for women, because they lose rights like maintenance (nafaqa) and maternity leave. This also applies to the 25% quota for women in the new election law. This is equity, not equality.

The reason why it is important to include women in politics is not only because Islam dictates it, but because it brings a woman’s touch into political decision-making. It is argued that women have a different perspective to men in the political debates and that women bring on board their experiences in the role as a caretaker for children and family into politics. There is an emphasis on the complementarity of roles between men and women. The underlying reasoning behind women’s inclusion into public sphere and particularly decision-making, is that they because of their biological make-up represent different values and interests to men. And in order to create balance in political decision-making, then the perspective of women are needed equal to that of men. According to Asma Turabi (Interview 2012);

Women are better in mercy and justice. Men do not consider the issues in the same way. Men do not consider the weak, the children and the disabled. Women are the most skilled to help and represent these groups.

Islamist women legitimized women’s participation in politics with reference to Islam, particularly noting that women have participated in public decision-making since the time of Prophet Muhammad. The fact that women do not have equal representation in political decision-making stands in contrast to Islam. It is history deviating from the authentic.

Implications of complementarity in politics

One of the primary indicators for the success of the UN millennium goal to “promote gender equality and empower women” is the “proportion of seats held by women in national parliament”. It also forms an important part of the new sustainable development goal 5 to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Complementarity has ushered women into politics in Sudan.

When the going gets tough in ‘hard’ politics, emotions are not welcome, and it is still an exclusively men’s game.

Islamists have argued for women’s political participation referring to women’s and men’s biological and complementary differences and the need to have both ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ elements included in decision-making. Women are expected to fulfil the role of the caring politician. It is in her biology as a nurturing and emotional being created by God. It is certain ‘soft’ political matters that require nurturing and caring emotions, typically these are an extension of women’s domestic role as a wife and mother. When the going gets tough in ‘hard’ politics, emotions are not welcome, and it is still an exclusively men’s game.

Notes

Notes

1 Fatima Mernissi (1991), The Veil and the Male Elite: A Feminist Interpretation of Women’s Rights in Islam, Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, pp. 1, 4.

2 Nagwa Mohamed Ali al-Bashir, Women in Public Life: The Experience of al-Akhwat al-Muslimat (Muslim Sisters): A Case from Sudan (master’s thesis, University of Khartoum, 1996), pp.95.

3 Hasan al-Turabi (1983), “The Islamic State” in John Esposito (ed.) Voices of Resurgent Islam, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 244.

The ‘Women and Peacebuilding in Africa’ project looks at the cost of women’s exclusion and the possibilities for their inclusion in peace talks, peacebuilding, and politics in Somalia, Algeria, northern Nigeria, South Sudan, and Sudan. The project also examines the struggle for women’s rights legal reform and political representation as one important arena for stemming the tide of extremism related to violence in Africa.

The three themes that make up the project are:

- Inclusion and exclusion in postconflict governance

- Women activists’ informal peacebuilding strategies

- Women’s legal rights as a site of contestation

The ‘Women and Peacebuilding in Africa’ project is a consortium between Center for Research on Gender and Women at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and Isis-Women’s International Cross-Cultural Exchange (Isis-WICCE). The project is funded by the Carnegie Foundation and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Liv Tønnessen