The role of local resistance committees in Sudan's transitional period

Local Resistance Committees (LRCs) emerged as a new political agent during the protests that led to the ousting of Omer al-Bashir. The role they played in toppling al-Bashir’s regime ironically places a responsibility on their shoulders ‘to protect’ the revolution. But who are the members of these committees? What was their role during the uprising? And what role can they play in Sudan’s transition to democratic rule?

The history of resistance

Sudan gained its independence in 1956, but quickly plunged into instability, civil strife, and economic impasse. Sudan politics has alternated between cycles of weak multi-party governments, military regimes, and people’s uprisings punctuated by transitions. The Islamist-led military takeover by Omer al-Bashir, known as the Inqaz regime, lasted for 30 years from 1989 up to 2019.

30 years of Inqaz rule left the country in shambles: The economy has been reeling under the weight of mismanagement and boycotts, and unemployment rates are high, especially among young people who make up more than 40 % of the population. They rightfully feel that they have been stripped of opportunities. The Islamists’ repressive measures rendered young people with a feeling of being denied their right to live their lives as they wanted. The Inqaz rule understandably fuelled discontent among Sudan’s youth in both urban and rural areas.

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/sudan-uprising-anything-can-happen, accessed on 3 October 2021.

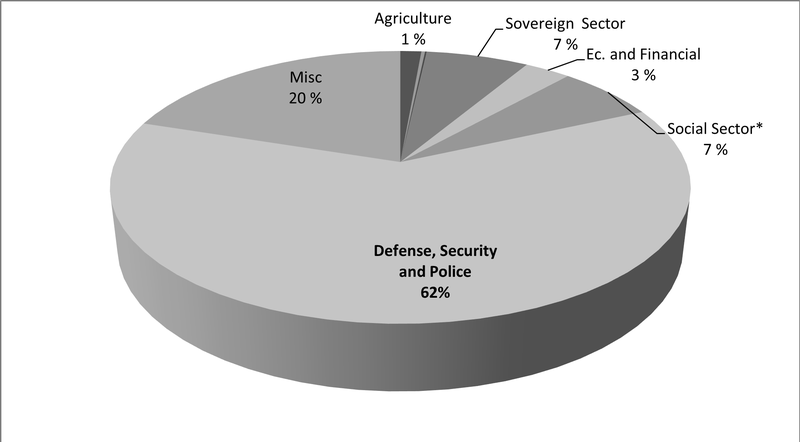

University students spearheaded youth protests as early as the 1990s, well before the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and SPLM alliance in 1990s. The sheer brutal use of force with which government forces responded to students and youth protests prompted some opposition leaders to call for armed protection for anti-government demonstrations, in what came to be known as ‘protected intifada’. But the ‘protected intifada’ failed according to the young protesters – they saw proof of its failure in developments following the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 and the secession of South Sudan in 2011, and in the government overspending on military and security (as shown below). Moving forward they started to organize local, non-violent, peaceful activities under slogan of Silmiyya,silmiyya diedd al-Haramiyya (peaceful, peaceful, against the thieves).

Government of Sudan Budget 2012, Ministry of Finance and National Economy, Khartoum, 2012.

The cumulative impact of students and youth resistance spurred the formation of LRCs, though the exact when, where and by who is a bone of contention between various parties. By 2010 and 2012 efforts began at earnest by youth groups to organize LRCs. In September 2013 the security forces ruthlessly put down demonstrations in Khartoum North where about 200 young demonstrators were gunned down, a massacre that drew internal and external condemnation of the government tactics. Cracks began to show among the ruling Islamists with splits and call for reform. Under growing pressure, President al-Bashir called for a national dialogue with the opposition in 2014, and after three years of deliberations the President incorporated some oppositions leaders in the government and re-shuffled the cabinet appointing a Prime Minister.

Cracks began to show among the ruling Islamists with splits and call for reform.

Fuelled by the government’s harsh economic policies and measures to remove subsidies of bread and fuel, demonstrations, roadblocks and burning of tyres became the order of the day at the behest of the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) that took over organizing and orchestrating peaceful protests in December 2018. In January 2019, the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) emerged as an umbrella organization for opposition parties and forces. However, the LRCs are the real change makers.

LRCs: A new change agent and political discourse

The membership base of the LRCs is drawn from young unemployed people from all socio-economic classes, but the committees’ activities have resonated particularly well with politically interested people from the middle class and among the poor. The members represent a large variety of ethnic backgrounds and come from different regions. The LRC movement strives to transcend the divides of political party affiliation, calling for a new path. LRCs were formed all over the country; however Khartoum gives a clear picture of their social-class nature and future outlook.

The LRC movement strives to transcend the divides of political party affiliation, calling for a new path.

Urban poor neighborhoods

Rural migrants and internally displaced persons dominate poor urban neighbourhoods such as Haj Yousif, Kalaka, Mayou-South Khartoum, Dar el-Salam, and Umbadda where anti-establishment tendencies flourish. While no leadership structure emerged, unemployed graduates with some experience in campus politics and social media tools provided the elementary political voices and acted as trusted guardians to a younger crowd. They are real ringleaders of the LRCs. During the protests, social outcasts were often rehabilitated as local heroes who stood their ground against the police, encouraging a spirit of hyper-masculine sacrifice.[1] The government’s repressive measures targeted youth in schools, universities, in cultural and sports activities, and the Public Order Police and Security forces disbanded tea sellers, rounded up these youngsters, and cleared the Nile Avenue during protests[2].

Middle class neighbourhoods

The middle class neighbourhoods are represented by Buri in Khartoum, Shambat in Khartoum North and al-Abasiyys in Omdurman. The LRCs in these neighbourhoods were the most organized and effective during the protests. They were also the most organized, and effective in mobilizing support on the streets.

Following the massacre of the Sit-in at the Army Headquarters (the protestors sit-in encampment around the army headquarters), these LRCs emerged as watch-dogs causing SPA, FFC and political parties not to barter the December revolution for government power. The Burri Lions, champions of Khartoum’s epicenter of protest, did not fall for political party tactics. At one point they shouted down a politician after calling for restraint[3].

Upper class neighbourhoods

During the protests, LRCs soon spread across the country, in both rich and poor neighbourhoods. Even Riyadh, the upper class, upscale neighbourhood of Khartoum, formed a resistance committee. Yet the Riyadh upper class LRC dynamic is quite different from the Kalakla middle class committees. While the members of the Kalakla LRCs are hungry for work, Riyadh’s agitators are motivated by the drop in their purchasing power. The Riyadh committee was formed through a Twitter outreach effort and includes many cosmopolitan upper-class university graduates.

While the members of the Kalakla LRCs are hungry for work, Riyadh’s agitators are motivated by the drop in their purchasing power.

Despite these differences in membership base and orientations, LRCs all over the country adopted a horizontal organization structure and developed tansiegiat (coordinating bodies) to synchronize and coordinate activities to unite behind major policy goals and also to support each other logistically.

The future of the LRCs

The youth’s disillusionment with the ‘old political club’ began a long time ago. The LRCs are advocating a discourse transcending tribal, ethnic and regional affiliations. Their horizontal organizational structure reflects their desire to maintain their autonomy and independence from political affiliations. The LRCs are the only force trusted by families of the martyrs and the general public. They have the potential and capacity to turn the youth movement into something bigger; to lift it from its narrow local platform to a national wide platform to support democratic transition.

But the road ahead is not without obstacles. The LRCs actual and potential power is targeted by main competing political forces. The military-militia as well as the political parties, from left, centre and right, are all trying to work their way into the LRCs, eventually co-opting them. Yet, the LRCs are fighting back. Recently an alliance of LRCs claiming to represent wider urban geographies have made public announcements declaring their independence from the politicking of the FFC and its members.

The LRCs actual and potential power is targeted by main competing political forces.

And according to al-Jizouli[4], in the new era of free speech, FFC leaders have been subjected to the unforgiving scrutiny of the committees and their revolutionary ideals. Many a hero of yesterday has been announced a villain. The committees have also taken to naming and shaming individuals accused of attempting to infiltrate their ranks or steer their course. These accusations have become a staple of media reporting on the committees, especially as powerful actors with money influence have moved in to sway LRCs away from their original mission and render them as clients and followers [5]. Reports by the press show growing LRC frustration in particular with FFC leadership, the former becoming critical of the latter in addressing the massacre of the Sit-in of 3rd June 2019, and issues pertaining to economic reform, and democratic transition.

Looking at the dynamics of the current transition process it is clear that neither the military nor the civilians in the Transitional Government can ignore the role of LRCs: The LRCs represent a centre of power aligned to a revolutionary agenda, continuing their work despite threats posed by the military, security and the Rapid Security Forces (RSF) to hijack the political process.

The Sudanese political landscape is in a state of flux. Peace talks with SPLM-N (al-Hilu) and SLM-Abdelwahid may add to the dynamics triggered by the Juba Peace Agreement in 2020 with the Revolutionary Front. Political realignment and repositioning are the order of the day. Feverish attempts to co-opt LRCs are flourishing. The LRCs are likely to be affected by a highly polarized political landscape. It remains to be seen whether they will preserve their autonomy and independence and act as a counter power to the military-militia forces in steering the December revolution on its course.

This Sudan blog post is written by Atta El-Battahani. He is a professor of political science at the University of Khartoum.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the ARUS project or CMI.

Notes

[1] .Magdi elGizouli, Mobilization and Resistance in Sudan’s Uprising, From neighbourhood committees to zanig queens, Rift Valley Institute, briefing paper, January 2020.

[2] . Later, security Chief Salah Goush confessed that this was a big mistake and contributed to youth frustration and anger against authorities. Of course, not to mention that reports of security making it easier for those using drugs (i.e Tramadol) to drug youth leaders.

[3] . Anonymous interviewer, 11 July 2020.

[4] . Magdi al-Jizouli is a intellectual, civil rights activist closely monitoring Sudan politics.

[5] . Magdi al-Jizouli, op.cit.